This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2007) |

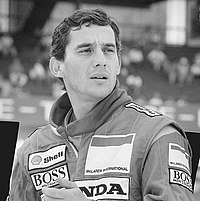

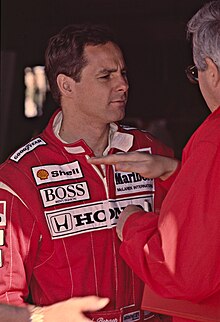

The 1988 FIA Formula One World Championship was the 42nd season of FIA Formula One motor racing. It featured the 1988 Formula One World Championship for Drivers and the 1988 Formula One World Championship for Constructors, which were contested concurrently over a sixteen-race series that commenced on 3 April and ended on 13 November. The World Championship for Drivers was won by Ayrton Senna, and the World Championship for Constructors by McLaren-Honda. Senna and McLaren teammate Alain Prost won fifteen of the sixteen races between them; the only race neither driver won was the Italian Grand Prix, where Ferrari's Gerhard Berger took an emotional victory four weeks after the death of team founder Enzo Ferrari. McLaren's win tally has only been bettered or equalled in seasons with more than sixteen races; their Constructors' Championship tally of 199 points, more than three times that of any other constructor, was also a record until 2002.

Drivers and constructors

editThe following drivers and constructors competed in the 1988 season. All teams competed with tyres supplied by Goodyear.

Team changes

edit- Naturally aspirated engines would become mandatory from 1989 onwards and this year already saw severe restrictions on the turbocharged units (see Regulation changes), so four teams took the gamble of making the switch early, hoping to give themselves an extra year to get used to the new regulations. Among them most notably was 1987 constructors' champion Williams; they were powered by the new Judd CV 3.5L V8. March and Ligier made the same choice. The other obvious way was to use the Ford-Cosworth DFZ V8's, but they ran a year behind in development, and Benetton had gained exclusive rights to use the superiour Cosworth DFR engine. Minardi made this choice, bringing the number of Cosworth-powered teams to ten in total. Looking for an advantage now that they couldn't rely on superior Honda turbo power, Williams added their reactive suspension system to the new Williams FW12. But 5% of the engine power was needed to run the computer-controlled system properly and, with the weight of the system, it made the already underpowered Judd V8 sluggish compared to its rivals.

- Osella kept using the Alfa Romeo 890T V8 turbo, but without factory support from the Italians, re-badged it as the "Osella V8". It produced around 700 bhp (522 kW), making it the second most powerful engine on paper, but it often proved slower than even the year-old Cosworths.

- McLaren and Lotus, customers of Honda, received the RA168E engine, specifically designed to cope with the limits placed on turbo output (see Regulation changes). This was hoped to give Honda teams an advantage, as all other engines had been designed in accordance to the previous rule set. Besides this, Lotus made what turned out to be the right choice, by stepping away from active suspension systems.

- The March team employed a new designer, who would go on to produce many successful F1 cars in his career: Adrian Newey designed the sleek-looking and aerodynamically effective March 881 for the team's second season back in F1.

- There were three new teams on the grid this year:

- BMS Scuderia Italia, using a Dallara chassis,

- Rial, ex-owner of the ATS team,[1] and

- EuroBrun, who had bought the remains of the Brabham team from Bernie Ecclestone. It would be the first time since 1961 that the Brabham team would miss on the grid. After losing use of the turbo BMW engines and failing to secure a replacement, and after missing the FIA's entry deadline for the 1988 season, team owner Bernie Ecclestone announced Brabham's withdrawal before the opening race in Brazil.

Driver changes

edit- Despite winning his third championship with Williams, Nelson Piquet left his team. A heated battle with teammate Nigel Mansell left the pair's relationship sour.[2] Riccardo Patrese was signed as his replacement. Piquet moved to Team Lotus, where a seat became available after it was announced that Ayrton Senna moved to McLaren to join Alain Prost.

- Before the 1987 Austrian Grand Prix, it was announced that Minardi driver Alessandro Nannini would replace Teo Fabi at Benetton. Fabi took out his frustration on his teammate Thierry Boutsen during the race, blocking him for many laps and not moving over for blue flags.

- In 1987, Julian Bailey became the first British driver to win a Formula 3000 race. This landed him a drive for Tyrrell F1 for 1988.[3] Bailey was one of the five drivers making his debut at the beginning of the season.

- Another ten driver switches happened in the lower-ranking teams.

Mid-season changes

edit- Martin Brundle was test driver for Williams in 1988 and fell in for Nigel Mansell at the Belgian Grand Prix, after Mansell was struck down with chickenpox.[4] For the Italian Grand Prix, Williams called upon Jean-Louis Schlesser to make his debut, since Brundle had prior commitments in IMSA. The French driver made himself (in)famous by crashing into leader Ayrton Senna when the Brazilian tried to lap him for the second time. The McLaren spun out, paving the way for a Ferrari 1-2 finish on home soil. It was McLaren's only race in the year they did not win.

- After failing to qualify in three consecutive races, Adrián Campos left Minardi unmotivated. The team replaced him with Pierluigi Martini, having raced for them in 1985 as well.

- Larrousse driver Yannick Dalmas fell ill near the end of the season. To replace him, Aguri Suzuki made his debut at his home race. For the final race, Pierre-Henri Raphanel stepped in, for his debut as well.

Calendar

editCalendar changes

editThe Austrian Grand Prix was dropped from the 1988 calendar due to safety concerns with the Österreichring, the narrow pit straight resulting in the 1987 race having to be restarted twice and Stefan Johansson hitting a small reindeer during the practice session, destroying his car and breaking his ribs in the process. This led to a re-organisation of the calendar, with the Belgian Grand Prix being moved from late May to late August to fill the slot traditionally occupied by the Austrian Grand Prix, and the Mexican Grand Prix being moved from mid-October to late May.

The Canadian Grand Prix returned after a year away, taking place in mid-June as the second race in a three-race North American tour, preceded by the Mexican Grand Prix and followed by the Detroit Grand Prix the following week.

Regulation changes

editTechnical regulations

editThe FIA continued their strategy from 1987, to make naturally aspirated engines more attractive, ahead of the ban on turbocharged engines from 1989 on:[5][6][7]

- The turbo boost was limited at 2.5 bar (36 psi), after it had already been brought down to 4.0 bar (58 psi) for 1987. The FIA handled this by mandating that the valves would "pop off" when the pressure went over the limit. This led to the turbo-powered cars producing approximately 300 bhp (220 kW) less than the year before.

- The fuel limit for turbo engines was set at 155 L (41 US gal), down from 195 L (52 US gal) for 1987, while teams running with a naturally aspirated engine could carry and use unlimited amounts of fuel during a race.

The FIA also introduced some new safety measures:[5][7]

- The driver's feet should be positioned behind the front axis of the car.

- The survival cell and fuel tank would now have to pass a static crash test.

Sporting and event regulations

edit- The Jim Clark and Colin Chapman trophies, awarded the previous year for drivers and constructors, respectively, who were using naturally aspirated engines, had been withdrawn as such engines would become mandatory from 1989 onwards,

- 31 drivers entered the first race, but it was decided that only 30 cars should be allowed to participate in the qualifying sessions. So pre-qualifying, which had been used in several races during the late 1970s and early 1980s, was re-introduced. For 1988, this consisted of five cars taking part in an extra session on Friday morning before the first session of qualifying proper, with the slowest car to miss out on the rest of the weekend.

- A permanent FIA race director would be present and active at all race meetings.[5][7]

Season report

editPre-season

editThe pre-season was a very contentious time, with many theories of the championship flying around: whether the Honda engines would prove successful with McLaren; whether Ferrari would be able to continue the trend set by the last two rounds of 1987, in which Gerhard Berger scored successive victories in Japan and Australia; whether Williams would be able to continue their success without Honda and Nelson Piquet; and whether reigning world champion Piquet could succeed in defending his title with the Honda-powered Lotus.

Pre-season testing in Rio de Janeiro at the newly named Autódromo Internacional Nelson Piquet (formerly known as the Jacarepaguá Circuit) was dominated by Ferrari seemingly continuing on with the form that saw Gerhard Berger win the final two races of 1987. Both Berger and Michele Alboreto set times during the Rio tests which were significantly faster than anyone else, and faster than had been recorded during the 1987 Brazilian Grand Prix, prompting rumours that the Scuderia had been running their cars without the FIA's mandatory pop-off valve, or had the valve set at 1987's 4.0 bar limit. The rumours seemed to carry weight when just a month later for the opening race at the same circuit when the pop-off valves were to be in use, neither Berger nor Alboreto could get near their testing times from the previous month, and both were well down on top speed compared to the McLaren and Lotus-Hondas.

Season

editRound 1 – Brazil

editFor the first race of the season in Brazil, with Ferrari being the only completely stable option and having dominated the Rio tests the previous month, many agreed that both Berger and Alboreto (should he find the motivation) would be in serious contention, and this was supported in Berger's second place behind Alain Prost's McLaren as well as setting the fastest race lap for the Ferrari. Though in a post-race interview Berger warned that Ferrari had a lot of work to do to catch up with Honda as the Ferrari V6 seemed to lack power compared to its rivals. Remarkable also, was Nigel Mansell's recovery from his accident in Japan to score a front row position for his non-turbo Judd-powered Williams on his first race back. Making Mansell's lap even more remarkable was that his Judd engined Williams FW12 was only timed at only 265 km/h (165 mph) on the long back straight compared to over 290 km/h (180 mph) for the Honda turbos of McLaren and Lotus. Mansell was the first non-turbo front row starter in Formula One since Keke Rosberg had qualified his Williams-Ford on pole at the same circuit for the opening race of the 1983 season.

Of the new teams and drivers, both EuroBruns qualified for the race, as did the Rial of Andrea de Cesaris, while Luis Pérez-Sala also qualified his Minardi-Ford. The Tyrrell-Ford of Julian Bailey failed to qualify, as did the turbocharged Zakspeed of Bernd Schneider. The converted F3000 Dallara-Ford of Alex Caffi failed to pre-qualify for its only race, with the full F1 chassis ready before the next race.

Senna's first race for McLaren got off to a bad start when the cars gear selector broke on the grid, causing a restart. The Brazilian was eventually disqualified for switching to the spare car after the green flag had been waved following the warm-up lap. At the time he had risen up to second place after starting from the pits. Making it look easy and confirming his mastery of the circuit, Prost won his fifth Brazilian Grand Prix in seven years, easing off over the last few laps to ensure he finished with enough fuel not to be underweight to finish 10 seconds in front of Berger, with World Champion Nelson Piquet finishing third in his first race for Lotus-Honda. With Derek Warwick (Arrows-Megatron), Alboreto (Ferrari) and Satoru Nakajima (Lotus-Honda) finishing 4th, 5th and 6th respectively the points were a clean sweep for the turbo powered cars, though Mansell and the Benettons of Boutsen and Nannini did run in the points for long periods of the race.

Round 2 – San Marino

editAt Imola however, it was plain to see that Steve Nichols' McLaren MP4/4, combined with the championship winning Honda V6 turbo, was in a class of its own. In qualifying both Senna and Prost were 3 seconds faster than the Lotus-Honda of Piquet in 3rd. At the end of the race Senna and Prost (who had almost stalled at the start and was only in 8th by the time the field got to Tosa, giving Senna a clear track while Prost took a number of laps to get to second) had lapped the entire field, with teammate Prost only 2.3 seconds behind a fuel conserving Senna at the finish. Indeed, both McLarens set faster race laps than anyone else had qualified. The McLarens lapping the field with 5 laps remaining was bad news for the normally-aspirated Benettons of Thierry Boutsen and Alessandro Nannini: as the lapped cars had a reduced distance to complete the race, the turbos of Piquet (Lotus) and Berger (Ferrari) had less need to stretch their fuel and now could afford to up their turbo boost if needed. Over the final 5 laps, Piquet pulled away from a challenging Boutsen (who was down on power due to a cracked exhaust), while Berger passed Nannini for 5th place on the last lap by cutting the grass at the Acque Minerali chicane, though no action was taken for cutting a corner to make a pass for position.

During qualifying, 1982 World Champion and the last driver to win the title driving a naturally aspirated car Keke Rosberg, said in an interview at about the new rules that if you ignored the McLarens it was quite a competitive race between the turbos and the 'atmos'. Considering that the Imola circuit had always been considered a power track that spelled good news for the FIA's turbo restriction rules, especially with drivers of the faster atmo cars, Nigel Mansell's Williams-Judd and the Benetton-Fords of Nannini and Boutsen, regularly challenging the turbos of Lotus-Honda (fastest through the speed trap in qualifying at 302 km/h (188 mph)), Ferrari and Arrows-Megatron, though the McLarens (which were 1.5 km/h slower at Tosa than Piquet in qualifying) were out of reach of everyone. The acceleration of the Honda V6 turbo in the sleek, lowline McLaren, and their downforce in the corners was unsurpassed. That, combined with who many considered the two best drivers in the world, saw the McLarens simply in another league at Imola. Though most in the F1 paddock and the press agreed that while Senna and Prost were the best drivers, all things being equal they weren't three seconds a lap faster than every one else.

For the first time since the team entered Formula One in 1976, both Ligiers failed to qualify for a race. Stefan Johansson, who could boast 11 podium finishes over the past 3 seasons with Ferrari and McLaren, could only manage 28th fastest, with 7 time Grands Prix winner René Arnoux (who also had 18 pole positions to his credit, including 2 at Imola) could only manage 29th fastest. Both drivers were over 8.5 seconds slower than Senna's pole time. The problem for the Ligiers was a lack of downforce from the Judd powered JS31 with Johansson telling that he had to use a wet weather technique even on a dry track.

Round 3 – Monaco

editDespite what many[who?] expected, the championship would hardly be considered boring[according to whom?] with the McLaren onslaught peaking with the drivers fighting in several feuds. At Monaco, after Alain Prost set the fastest lap, Senna refused to accept that his teammate could be driving faster than he was, especially after Senna outqualified Prost by over a second. Senna pushed and after taking back the fastest lap, Ron Dennis got on the radio and told his drivers to effectively 'cool it' as Senna's lead was 50 seconds with only 12 laps remaining. Senna, his rhythm broken, then had a major lapse in concentration and hit the wall at Portier. What made Senna's mistake all the more astounding was that he had completely dominated the weekend, taking pole by 1.4 seconds from Prost (who was 1.2 seconds faster than Berger's 3rd placed Ferrari) and from the start of the race had simply run away and hid from the field.

Prost, who had made the best start but was passed in quick succession by Senna and Berger when he couldn't engage second gear, spent 54 laps trying to find a way around the Ferrari as his teammate pulled away by almost a second per lap. The McLaren got alongside the Ferrari many times past the pits but simply ran out of room to pass before Sainte Dévote. Finally, on lap 54, Prost got a good run out of the final turn and was able to out brake Berger going into Sainte Dévote. He then set about pulling away from the Ferrari while also trying to put some pressure on Senna. Thanks to Senna's crash, Berger picked up second place behind Prost with teammate Alboreto third.

After Senna's crash, the McLaren team didn't see or hear from him until that night as he didn't return to the pits until the team was packing up after the race. As the Brazilian lived in Monaco, the general belief was that he went back to his home to contemplate losing a race he had totally dominated.

Round 4 – Mexico

editIn Mexico, it was nearly a repeat of San Marino: McLaren 1–2, with this time only one other driver on the lead lap. Gerhard Berger had picked up his third podium in four races, giving him the edge on Piquet and Alboreto for the title of "Best of the Rest" – the race for third. As expected, turbo cars dominated in the thin air of Mexico City, with the front three rows of the grid shared between the McLaren-Hondas, Ferraris, Lotus-Hondas. This dominance continued in the race. Behind the Prost-Senna 1–2 came a Ferrari 3–4 with Alboreto finishing behind his teammate, while Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever finished 5th and 6th after a race long dice in their Arrows-Megatron turbos. Warwick and Cheever would later remark that their race was "good fun".

In the thin air of Mexico City's high altitude, the turbos were able to perform at their optimum, while the naturally aspirated cars actually lost approximately 20–25% of their power. This advantage allowed the Zakspeed of Bernd Schneider to qualify an impressive 15th for his first Grand Prix start in what wasn't the most competitive car in the field. Incredibly though, the turbocharged Osella of Nicola Larini with its ancient "Osella V8" (a re-badged Alfa Romeo 890T first seen in 1983), allegedly the most powerful engine in the field, failed to qualify.

The last qualifying session was dominated by Philippe Alliot's terrifying crash after he lost control of his Lola, coming out of the Peraltada curve that leads onto the pit straight (the Peraltada, being slightly banked, was being taken at speeds in excess of 240 km/h (149 mph) in qualifying). After riding the outside curbing, the car suddenly pulled hard right, cut across the track and collided with the pit wall, barrel-rolling down the straight and back across the track, immediately disintegrating, and in the end stopped upside down in the middle of the track. Remarkably, Alliot was not only unhurt, but the Larrousse team was able to rebuild the car overnight and Alliot was able to take his place on the starting grid.

The fastest atmo qualifier, the Benetton-Ford of Alessandro Nannini, finished in 7th place. The Italian, who finished just in front of teammate Thierry Boutsen after another race long duel between teammates, finished the race without a point and in severe pain from a pinched nerve in his right foot from never having to drive as hard for so long.

Honda's 1–2 finish with McLaren had its flip side though as both Nelson Piquet and Satoru Nakajima failed to finish due to blown Honda engines.

Round 5 – Canada

editAfter not racing in Canada in 1987 due to a sponsorship dispute, Formula One returned to the Circuit Gilles Villeneuve for the 1988 Canadian Grand Prix. The circuit had been changed since the last visit in 1986, with the pits relocated to the opposite end of the circuit, the new complex gaining general approval from those who mattered, the teams themselves. Canada again proved a repeat of the McLaren onslaught, this time Boutsen's Benetton being the only other car on the lead lap, and 50 seconds behind. Canada saw the first on-track fight for the lead between the two McLaren drivers. Prost won the start and led until lap 19 when Senna passed him under braking for the L'Epingle Hairpin. The Brazilian then pulled away from his teammate to win by 5 seconds, with Boutsen and further 46 seconds back in third.

Nelson Piquet's season of disappointment continued with a 4th-place finish in his Lotus-Honda, again one lap down on the McLarens. After qualifying 6th, the reigning World Champion was passed early on by ex-teammate Nigel Mansell's Williams-Judd, and then spent many laps fighting off the AGS-Ford of Philippe Streiff until the Frenchman suffered suspension failure on lap 41.

Round 6 – Detroit

editThis was repeated in Detroit, however this time third placed Boutsen failed to stay on the lead lap as Senna took his second victory in a row, and his third in a row in Detroit, making it six out of six for McLaren and Honda. Prost finished 38.7 seconds behind in second. For the first time since Brazil, there was something other than a McLaren on the front row. Gerhard Berger qualified second behind Senna (who took his record 7th straight pole position), with Alboreto third and Prost only managing fourth on the grid on his least favorite track on the calendar. This would prove to be the final ever Formula One Detroit Grand Prix, the temporary street circuit failing to meet the FIA's minimum pit requirements.

Round 7 – France

editThe French Grand Prix at Paul Ricard saw another 1–2 for McLaren, this time with Prost at the helm for his home Grand Prix, followed by the Ferraris, though this time Alboreto led home Berger with the Italian the only driver not lapped by the McLarens. Piquet raced a brilliant race, despite losing second gear, to come through for a fifth place. For the first time in 1988, Ayrton Senna was not on pole position. In France it was French hero Prost who qualified fastest almost half a second up on his teammate. The race saw the second true fight of the season between the McLarens, with Prost coming out on top after a brave passing move at the ultra fast Courbe de Signes when Senna had been momentarily baulked by the Dallara of Alex Caffi and the Minardi of Pierluigi Martini.

At the team's home Grand Prix, Ligier suffered the embarrassment of neither René Arnoux (who turned 40 the day after the race) or Stefan Johansson being able to qualify for the race.

Round 8 – Britain

editAt the wet British Grand Prix at Silverstone, Nigel Mansell surprised all by scoring a second place for an atmos car for his first finish of the season after seven races of DNFs, a result which definitely pleased the hordes of British fans who were still gripped in Mansell-mania despite the driver's (or rather, the car's) lacklustre performance through the year. Senna won, with the podium rounded off by Nannini, proving that Silverstone was an unusually good race for the atmos cars. Silverstone also saw the only non-McLaren pole position when Gerhard Berger claimed pole in his Ferrari. It was also the only time neither McLaren qualified on the front row as Alboreto qualified second.

Mansell's race was helped when the 'reactive suspension' used on the Williams FW12 was dumped by the team after Friday qualifying and a conventional suspension was put in its place. Team Technical Director Patrick Head called the work "a bit of a bodge", but the new suspension transformed the car and allowed Mansell and teammate Riccardo Patrese to enter the race with confidence for the first time all season (after Friday qualifying, Patrese had been 30th and last, almost 21 seconds slower than provisional pole man Alboreto).

Prost got a horror start and was down in 9th at the end of the first lap with BBC commentator and 1976 World Champion James Hunt noting as early as lap 2 that his Honda engine was badly misfiring. Prost was later lapped by his teammate going into Woodcote in a move that also saw Senna take the lead for the first time from Berger. Prost suffered his first DNF of the season when he retired on lap 24 citing an engine misfire and poor handling, though in complete contrast to his win in France a week earlier, he was attacked in the French press, many of whom felt he had simply given up.

McLaren had dominated, winning the first eight races of the season, with Prost and Senna winning four each. Prost led the championship with 54 points from Senna on 48 and Gerhard Berger on 21. McLaren were making a mockery of the Constructors' Championship having scored 102 points, 68 in front of second placed Ferrari.

Round 9 – Germany

editGermany proved a return to the year's trend, with the long straights of Hockenheim showcasing the brute strength of the turbos, with the only atmos car on the lead lap behind both McLarens and Ferraris respectively being Capelli's March. Capelli recorded the fastest 'atmo' speed trap of the season during qualifying, the Judd V8 pushing the March 881 to 312 km/h (194 mph), though this was significantly slower than the McLarens at 333 km/h (207 mph), and Ferraris at 328 km/h (204 mph). Unable to exploit the power of their Megatron turbos thanks to the pop-off valve regularly cutting in at around 2.3 bar instead of the full 2.5 bar limit, the Arrows A10Bs of Derek Warwick and Eddie Cheever struggled, only trapping at around 315 km/h (196 mph).

Gerhard Berger survived a high speed spin in qualifying. His Ferrari was attempting to pass the EuroBrun of Oscar Larrauri and the Arrows of Eddie Cheever on the final straight before the stadium section of the track. Berger went to his left to pass both cars only to find Cheever had done the same to pass Larrauri, and the American had what was left of the road. At almost 280 km/h (174 mph), the Ferrari put its left wheels on the grass, sending it into a spin between the Arrows and EuroBrun. Luckily, Larrauri had only been cruising at the time and was able to avoid the spinning Ferrari. Berger managed to stop his car before it hit the barrier on the opposite side of the track.

In the second wet race in a row, Senna took the win from Prost, with Berger taking the bottom step of the rostrum. Alessandro Nannini set his first career fastest lap in his Benetton-Ford V8. The Italian had been in 4th place before having to pit to fix a broken throttle bracket which cost him 4 laps and almost 20 places and angrily drove the rest of the race flat out, setting a time that was 1.856 seconds faster than the next best set by Prost. Defending World Champion Nelson Piquet made the strange decision to start the race on slick tyres. It proved to be the wrong choice as his Lotus aquaplaned on the wet surface and clouted the tyre barrier going into the Ostkurve chicane on the first lap. Larrousse driver Philippe Alliot would later repeat Piquet's mistake. He changed from wets to slicks just 8 laps later and while being lapped by Senna, went offline and aquaplaned into the same tyre barrier the Lotus had hit. Like Piquet's Lotus, Alliot's Lola was out on the spot with rear suspension damage.

Round 10 – Hungary

editAt the following Grand Prix at Hungary, Senna secured his 24th pole position, securing the third highest total after legendary champions Jim Clark and Juan Manuel Fangio, backing his qualifying effort up by taking victory over teammate Prost by just over half a second. This was Senna's sixth win of the season, and third on the trot, with Prost on just four wins.

Despite suffering from Chickenpox, Nigel Mansell secured his first front row start since the opening race in Brazil. On the tight and twisty Hungaroring, the only turbo powered cars in the top 7 were the McLarens, with Prost down in 7th place. Mansell got the better of the start and briefly led, but before the first turn the power of the Honda turbo told and Senna was through into the lead. Mansell and teammate Riccardo Patrese then pressured Senna until Mansell spun his Williams on lap 12, dropping him to 4th place. Patrese then set about taking the lead from Senna but was forced to drop back with engine trouble and would eventually finish 6th.

Prost's race was better than qualifying, and though he again made a slow start and was 9th at the end of the opening lap, he fought his way up to second behind Senna on lap 47. On lap 49 he took the lead from Senna down the pit straight in a breathtaking move where he not only passed Senna but also the lapped Yannick Dalmas and Gabriele Tarquini. Unfortunately his burst of speed also saw him run wide at the first corner allowing Senna to dive underneath and re-take the lead. From that point Prost's McLaren developed a vibration which saw him drop back from Senna, though he again charged late in the race and was only half a second behind at the finish. Thierry Boutsen once more finished "best of the rest" in his Benetton, finishing half a minute behind the McLarens, his race not helped by a broken exhaust which robbed the Ford DFR of power. Rounding out the points were Berger, Gugelmin and Patrese. After a race long duel, the Lotus pair finished out of the points in 7th and 8th respectively, with Satoru Nakajima gaining praise for finishing in front of his more illustrious teammate. Nakajima and Piquet finished 3 laps behind the McLarens.

Round 11 – Belgium

editThe 1988 Belgian Grand Prix showed Prost one thing: to not change his set-up at the last minute. All through the year, Prost's better feel at setting up a car was not only noticed by his teammate, but mimicked. Senna had used Prost's set-ups for every race thus far, and the race at Spa was no different. This annoyed Prost, and he changed his aero-settings at the last minute (running less wing with the hopes of being faster on the straights and the long run from Stavelot to the Bus Stop chicane), hoping to give himself an edge over the pole-sitting Senna. At the start, Prost took the lead after Senna suffered wheel spin, but on the first lap Senna with greater downforce was noticeably faster through Eau Rouge. Despite running with more wing than his teammate, Senna was able to then slipstream Prost up the Kemmel Straight and easily out braked him into Les Combes. From there Senna steadily drew away from his teammate who was unhappy with the balance of his car after his last minute setting change, going on to take an easy 30 second win. Third and fourth was filled by the two Benettons, however they were both disqualified from the results[8] long after the race had ended for using illegal fuel (in fact, the DQ was not known until after the season had ended meaning most publications showed the Benettons as finishing 3rd and 4th). This saw Ivan Capelli gain his first ever podium in Formula One. The 1–2 for McLaren meant that the points gap became big enough that Ferrari lost any chance of catching them in Constructors' Championship, securing McLaren one of the earliest recorded Constructors' Championship victories.

After racing in Hungary against doctors orders, Nigel Mansell was forced to miss the Belgian Grand Prix through illness and was replaced by Martin Brundle, who after four years in F1 was driving a V12 Jaguar XJR-9 for Tom Walkinshaw Racing in the 1988 World Sportscar Championship (Brundle would win that championship). After qualifying 12th, and actually being fastest in the 2nd, wet qualifying session, Brundle finished in 7th place, one lap behind his former British Formula 3 rival Senna.

Two weeks before the Belgian Grand Prix, Formula One lost its best known and one of its most loved people. Enzo Ferrari, the founding father of Ferrari and its F1 team Scuderia Ferrari, died on 14 August at the age of 90. In the first race since the death of their teams founder, Berger and Alboreto qualified 3rd and 4th respectively with Alboreto being the fastest through the speed trap on the Kemmel Straight at 312 km/h (194 mph). Both were a DNF in the race however, Berger out on lap 11 with injection trouble, and while Alboreto's engine blew on lap 35.

Round 12 – Italy

editBefore the Italian Grand Prix, Prost was quoted as saying that, as it was very possible that McLaren would take out a perfect sixteen out of sixteen victories, the winner would be determined between which McLaren driver would take the most wins, and on the chance they both took eight, it would be determined on their second places, which at the time Prost had more of despite having fewer wins. This meant Prost with 4 wins to Senna's 7 could only let Senna win one more time.

Monza, being another high speed circuit, would prove to be another McLaren dominated race, with both sitting on the front row, again with both Ferraris behind. The race fell into regular routine as Senna led from the start and Prost close behind. Prost had actually won the start, but as he changed gear from 1st to 2nd, his Honda engine began to misfire, allowing Senna to power past before the Retifillo chicane. At the end of the first lap with Senna holding a 2-second lead, Prost, correctly believing the misfire was bad enough that he wouldn't finish the race, turned his turbo boost up to full and gave chase. However, on lap 35 of 51, Prost's championship hopes seemed to evaporate when his Honda engine finally blew. The tifosi cheered as their drivers were shifted to second and third, albeit some 30 seconds behind Senna, and Honda were left embarrassed with one of their engines expiring on their main rivals (Ferrari) home track. Unfortunately for McLaren though, what Prost had done was to force Senna to use too much fuel in his desire to stay in the lead (many in the pits, including his former Lotus team boss Peter Warr believed that Senna had effectively been suckered by Prost and should have realised that if he was using too much fuel then Prost was also, something Prost did not usually do). This forced Senna to back off over the last 16 laps in order to ensure a finish, and it allowed the Ferraris to close the gap from 30 seconds when Prost retired, to just over 5 seconds with just two laps remaining as Senna came up to lap the Williams of Jean-Louis Schlesser, standing in for the still unwell Nigel Mansell.

Senna, knowing the Ferraris were closing in, dived under Schlesser's Williams at the Rettifilo chicane instead of waiting for the long, fast Curva Grande that would follow. Senna took his normal line through the corner while Schlesser moved over to give him room. The Williams locked its brakes in the dust and marbles on the edge of the circuit and slid wide. Schlesser (a noted rally driver who was used to such things) then regained control and turned the Williams to avoid the sand trap and found Senna had not allowed any room for the Frenchman to rejoin the circuit. The Williams T-boned the right rear tyre of the McLaren, breaking its rear suspension and destroying any hopes of a perfect winning season for McLaren. The tifosi erupted as the #12 McLaren was beached on a curb and out of the race; Gerhard Berger and Michele Alboreto sat first and second, where they remained at the finish only half a second apart. The victory was made poignant by the fact that it was the first Italian Grand Prix since Enzo Ferrari's death. Both drivers and team dedicated the victory to the "old man". This race would prove to be the only chink in McLaren's perfect year and their only double retirement.

Arrows, whose engine guru Heini Mader had finally solved the Megatron engine's pop-off valve problem giving them comparable power to the Honda and Ferrari engines (approximately 640 bhp (477 kW)), finished 3rd and 4th, with Cheever gaining the final spot on the rostrum just six-tenths in front of Derek Warwick. It would prove to be the final podium finish for both Arrows with their old BMW M12 engine (re-badged as Megatron in 1987) which had been introduced to F1 with the Brabham team back in 1982. With full power now available, during qualifying Cheever pushed his Arrows A10B to 200 mph (322 km/h), comfortably faster than the McLarens and Ferraris which were timed at 192 mph (309 km/h).

Round 13 – Portugal

editThe following Grand Prix in Portugal proved to be an exciting affair, for all but Ayrton Senna who suffered race long with handling troubles. He ended sixth while Prost retook the championship lead by obtaining his fifth victory of the year. March driver Ivan Capelli secured his second career podium with a brilliant second, with Boutsen once again finishing third in his Benetton. As the field finished the first lap of the race, Prost, who had claimed his second pole of the year (and pulled a psychological ploy on Senna by setting his time early in the final session, then spending the rest of the session lounging in the McLaren pits wearing jeans and a T-shirt, almost daring the Brazilian to beat him), pulled out of Senna's slipstream to pass his teammate for the lead down the straight. In a famous vision, Senna almost pushed his teammate into the pit wall at over 280 km/h (174 mph), something which didn't please the race winner. This was after Prost had tried to block Senna and pushed him close to the grass during one of the aborted starts.

Round 14 – Spain

editAt the Spanish Grand Prix, Prost secured his sixth win of the season, again in an attempt to delay an almost inevitable eighth race win for Senna – that would secure his first of three championships. As in Portugal, Senna suffered from fuel gauge problems, as well an overheating engine and was lucky to secure fourth. Nigel Mansell doubled his British Grand Prix efforts and scored another six points. He moved into second early and while never seriously threatening Prost for the lead, it was only a slow stop for tyres on lap 47 which prevented the Englishman from pressuring the Frenchman late in the race. Alessandro Nannini continued to impress when drove a steady race to finish third in his Benetton.

During qualifying, Grand Prix's most experienced driver Riccardo Patrese was fined $10,000 for brake testing the Tyrrell of Julian Bailey. Patrese's action, which caused the Tyrrell to hit the back of the Williams, fly into the air and off the track into a gravel trap, was widely condemned by those in the paddock. One unnamed driver was quoted as saying "I hope they fine him his bloody retainer. There are enough accidental shunts in this business without people actually trying to cause them....."

Round 15 – Japan

editThe penultimate round in Japan was, once again, where the title was decided. This time it was the end of the weekend, and not the beginning. Prost made a superb start to the lead, whilst Senna stalled, lucky in the fact that Suzuka had a sloping grid, helping to start his car. Senna knew he had nothing to lose and everything to gain in this race, and knew he could seal the championship here. By the end of the lap he had already made up six positions, and by the fourth lap he was sitting in fourth position. The top six cars were all sitting very close and when the rain started to fall, so did Prost. Capelli took this chance to become the first naturally aspirated car to lead a Grand Prix in over 4 years, thrilling the March team. Unfortunately, this was not to last as his electronics would eventually fail. By then, Senna was hot on the tail of Prost. Prost disliked the wet, and his failing gearbox only added to the Brazilian's chances. When the pair came round to lap some back-markers, as Prost was caught up with de Cesaris, Senna went past to take the lead, and set three consecutive fastest laps and setting a new lap record. As he was now in front of the field of competitors and due to become world champion, he signaled to stop the race. However, the race ran its full distance and Honda were reveling in their 1–2 finish, whilst Prost was bitter, but readily accepted that Senna was a deserving champion.

Other than those with Honda engines, the Japanese fans had two local drivers to cheer for the first time. Japanese Formula 3000 champion Aguri Suzuki was substituting for the sick Yannick Dalmas in the Larrousse team (Dalmas would later be diagnosed with Legionaire's Disease). Suzuki joined Satoru Nakajima as the only Japanese drivers in F1 at the time. The much-maligned Nakajima won praise at the meeting when he drove despite finding out only 30 minutes before the first practice session that his mother had died that morning. The inspired Japanese driver was faster than his World Champion teammate Piquet on the first day of qualifying, and matched the Brazilian's time to the thousandth of a second during the second session.

Round 16 – Australia

editMcLaren secured their 12th 1–2 qualifying for the season, with Senna setting his record 13th pole for the year, again doing his last minute act by literally beating Prost's time on the last lap of qualifying. In the last turbo Formula One race until the 2014 season, Bernd Schneider failed to qualify his Zakspeed, while Nicola Larini failed to pre-qualify the Osella. A relaxed Nigel Mansell, in his last race in his first spell for Williams, qualified 3rd, though he wasn't confident going into the race as both he and Riccardo Patrese had suffered brake trouble all through practice and qualifying and the Adelaide Street Circuit had been notoriously hard on brakes in its 3 race history.

Before the race Gerhard Berger told both Prost and Senna that with it being the last race for the turbos he was going to "go for it" and run the race with full turbo boost. He reasoned it was better to go out in the lead rather than just drone around in the wake of the McLarens. True to his word, Berger led the race by using maximum turbo boost in his engine and had passed Prost for the lead on lap 14. His race was only to last another 9 laps though as he crashed with René Arnoux on lap 25. After that the race turned into another McLaren demonstration, though late in the race Nelson Piquet did briefly threaten Senna who had been having gear selection problems almost from the start. Mansell's fear of the Williams's brakes came to fruition when he spun into the barriers on lap 65 simply through having no brakes left. He had been in fourth place at the time just in front of Patrese, but had not been able to truly challenge Piquet who was able to use Honda power on the 900-metre-long Brabham Straight to keep his former teammates at bay.

Prost would go on to win in Adelaide, leading home Senna and outgoing champion Nelson Piquet giving Honda turbos a fitting 1–2–3 finish in the final race of the first turbo era in Formula One. Prost's win over Senna in Australia saw him score eleven more points in total than the Brazilian, but only the eleven highest scores counted, with Senna's eight wins and three seconds giving him a total of 90 points to Prost's 87. While Prost agreed that Senna deserved his championship win,[citation needed] he went on to be a proponent of the 1990s scoring system, where all results would count to the final results with the winner scoring 10, not 9, points.

Summary

editIncredibly, of the 14 races Alain Prost finished in 1988 he would record seven wins and seven second places, yet it wasn't enough to win the championship. His wins total equaled the single season record he himself had equalled in 1984 (Jim Clark had won 7 races in 1963) when he had also lost the world championship to then McLaren teammate Niki Lauda. However, unlike Lauda who scored 5 wins and it was his regular points finishes that gave him his 3rd championship, the wins record now belonged to Senna who finished with eight wins. Senna also set the single season pole winning record by claiming the fastest time on thirteen occasions during the year, finishing the season with 29 career pole positions, only four behind the record, which was another held by the great Jim Clark.

In Adelaide, FOCA boss Bernie Ecclestone summed up the season by saying that what McLaren had actually done was nothing more than their usual professional job and that they didn't really do anything exceptional. With the Honda turbo they clearly had the best engines, and in Senna and Prost they had the two best drivers. The problem was that just about every other team performed well below par and the McLarens were rarely challenged. He then jokingly added that all the teams, including McLaren, would have to up their performance in 1989 as Brabham (which he had sold to EuroBrun owner Walter Brun) would be back in Formula One.

While the McLaren-Honda cars had dominated the 1988 Formula One season like no-one had before, the FIA's rules to limit turbo cars' boost and fuel tank size had the desired effect of bringing the atmospheric cars back into contention. This was shown by front row starts for Nigel Mansell in Brazil and Hungary, as well as three second-place and eight third-place finishes for the non-turbo cars, and on each occasion that a non-turbo car finished on the podium, the only cars to finish in front of them were the all-conquering McLaren-Hondas.

Results and standings

editGrands Prix

editScoring system

editPoints were awarded to the top six classified finishers. For the Drivers' Championship, the best eleven results were counted, while, for the Constructors' Championship, all rounds were counted.

Numbers without parentheses are championship points; numbers in parentheses are total points scored. Points were awarded in the following system:

| Position | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Source:[9] | ||||||

World Drivers' Championship standings

edit

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

† Driver did not finish the Grand Prix, but was classified as he completed over 90% of the race distance.

* Only the best 11 results counted toward the championship.[10] Prost scored 105 points during the year, but only 87 points were counted toward the championship. Senna scored 94 points, with 90 points counted toward the championship by virtue of winning more races. Thus, Senna became the World Champion, although he did not score the most points over the course of the year.

World Constructors' Championship standings

edit| Pos | Constructor | Car no. |

BRA |

SMR |

MON |

MEX |

CAN |

DET |

FRA |

GBR |

GER |

HUN |

BEL |

ITA |

POR |

ESP |

JPN |

AUS |

Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | McLaren-Honda | 11 | 1 | 2F | 1 | 1F | 2 | 2F | 1PF | Ret | 2 | 2F | 2 | Ret | 1P | 1F | 2 | 1F | 199 |

| 12 | DSQP | 1P | RetPF | 2P | 1PF | 1P | 2 | 1 | 1P | 1P | 1P | 10P | 6 | 4P | 1PF | 2P | |||

| 2 | Ferrari | 27 | 5 | 18 | 3 | 4 | Ret | Ret | 3 | 17 | 4 | Ret | Ret | 2F | 5 | Ret | 11 | Ret | 65 |

| 28 | 2F | 5 | 2 | 3 | Ret | Ret | 4 | 9P | 3 | 4 | RetF | 1 | RetF | 6 | 4 | Ret | |||

| 3 | Benetton-Ford | 19 | Ret | 6 | Ret | 7 | Ret | Ret | 6 | 3 | 18F | Ret | DSQ | 9 | Ret | 3 | 5 | Ret | 39 |

| 20 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 3 | 3 | Ret | Ret | 6 | 3 | DSQ | 6 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 5 | |||

| 4 | Lotus-Honda | 1 | 3 | 3 | Ret | Ret | 4 | Ret | 5 | 5 | Ret | 8 | 4 | Ret | Ret | 8 | Ret | 3 | 23 |

| 2 | 6 | 8 | DNQ | Ret | 11 | DNQ | 7 | 10 | 9 | 7 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 7 | Ret | |||

| 5 | Arrows-Megatron | 17 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 7 | Ret | Ret | 6 | 7 | Ret | 5 | 4 | 4 | Ret | Ret | Ret | 23 |

| 18 | 8 | 7 | Ret | 6 | Ret | Ret | 11 | 7 | 10 | Ret | 6 | 3 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | |||

| 6 | March-Judd | 15 | Ret | 15 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 8 | 4 | 8 | 5 | Ret | 8 | Ret | 7 | 10 | Ret | 22 |

| 16 | Ret | Ret | 10 | 16 | 5 | DNS | 9 | Ret | 5 | Ret | 3 | 5 | 2 | Ret | Ret | 6 | |||

| 7 | Williams-Judd | 5 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 2F | Ret | Ret | 7 | 11 | Ret | 2 | Ret | Ret | 20 |

| 6 | Ret | 13 | 6 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 8 | Ret | 6 | Ret | 7 | Ret | 5 | 6 | 4 | |||

| 8 | Tyrrell-Ford | 3 | Ret | 14 | 5 | DNQ | 6 | 5 | Ret | Ret | 11 | Ret | 12 | DNQ | Ret | Ret | 12 | Ret | 5 |

| 4 | DNQ | Ret | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | 9 | DNQ | 16 | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | 12 | DNQ | DNQ | 14 | DNQ | |||

| 9 | Rial-Ford | 22 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 9 | 4 | 10 | Ret | 13 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 8 | 3 |

| 10 | Minardi-Ford | 23 | Ret | 16 | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | 6 | 15 | 15 | DNQ | Ret | DNQ | Ret | Ret | Ret | 13 | 7 | 1 |

| 24 | Ret | 11 | Ret | 11 | 13 | Ret | NC | Ret | DNQ | 10 | DNQ | Ret | 8 | 12 | 15 | Ret | |||

| — | Lola-Ford | 29 | Ret | 12 | 7 | 9 | DNQ | 7 | 13 | 13 | 19 | 9 | Ret | Ret | Ret | 11 | 16 | DNQ | 0 |

| 30 | Ret | 17 | Ret | Ret | 10 | Ret | Ret | 14 | Ret | 12 | 9 | Ret | Ret | 14 | 9 | 10 | |||

| — | Dallara-Ford | 36 | DNPQ | Ret | Ret | Ret | DNPQ | 8 | 12 | 11 | 15 | Ret | 8 | Ret | 7 | 10 | Ret | Ret | 0 |

| — | AGS-Ford | 14 | Ret | 10 | Ret | 12 | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | 10 | Ret | 9 | Ret | 8 | 11 | 0 |

| — | Coloni-Ford | 31 | Ret | Ret | Ret | 14 | 8 | DNPQ | DNPQ | DNPQ | DNPQ | 13 | Ret | DNQ | 11 | DNPQ | DNPQ | DNQ | 0 |

| — | Ligier-Judd | 25 | Ret | DNQ | Ret | Ret | Ret | Ret | DNQ | 18 | 17 | Ret | Ret | 13 | 10 | Ret | 17 | Ret | 0 |

| 26 | 9 | DNQ | Ret | 10 | Ret | Ret | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | 11 | DNQ | Ret | Ret | DNQ | 9 | |||

| — | Osella | 21 | DNQ | EX | 9 | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | Ret | 19 | Ret | DNPQ | Ret | Ret | 12 | Ret | Ret | DNPQ | 0 |

| — | EuroBrun-Ford | 32 | Ret | DNQ | Ret | 13 | Ret | Ret | Ret | DNQ | 16 | DNQ | DNPQ | DNPQ | DNPQ | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | 0 |

| 33 | Ret | NC | EX | EX | 12 | Ret | 14 | 12 | Ret | 11 | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | 13 | DNQ | Ret | |||

| — | Zakspeed | 9 | DNQ | Ret | Ret | 15 | 14 | DNQ | EX | DNQ | 14 | DNQ | Ret | Ret | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | 0 |

| 10 | DNQ | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | DNQ | 12 | DNQ | 13 | Ret | DNQ | DNQ | Ret | DNQ | |||

| Pos | Constructor | Car no. |

BRA |

SMR |

MON |

MEX |

CAN |

DET |

FRA |

GBR |

GER |

HUN |

BEL |

ITA |

POR |

ESP |

JPN |

AUS |

Pts |

Non-championship event results

editThe 1988 season also included a single event which did not count towards the World Championship, the Formula One Indoor Trophy at the Bologna Motor Show.

| Race name | Venue | Date | Winning driver | Constructor | Report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formula One Indoor Trophy | Bologna Motor Show | 7, 8 December | Luis Pérez-Sala | Minardi | Report |

Notes

edit- ^ Only the best 11 results counted towards the Drivers' Championship. Numbers without parentheses are championship points; numbers in parentheses are total points scored.

References

edit- ^ "Rial Racing". F1Technical.net. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ^ "Nelson Piquet Profile". grandprix.com. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ "Lunch with...Julian Bailey". motorsportmagazine.com. 7 July 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ ITV F1. "Martin Brundle". Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Steven de Grootte (1 January 2009). "F1 rules and stats 1980-1989". F1Technical.net. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ "Engine rule changes through the years". formula1-dictionary.net. Retrieved 30 January 2024.

- ^ a b c "Safety improvements in F1 since 1963". AtlasF1. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Grand Prix Results: Belgian GP, 1988 Retrieved from www.grandprix.com on 2 December 2009

- ^ "World Championship points systems". 8W. Forix. 18 January 2019. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- ^ Peter Higham, The Guinness Guide to International Motor Racing, 1995, page 126

External links

edit