The Eighth Crusade was the second Crusade launched by Louis IX of France, this one against the Hafsid dynasty in Tunisia in 1270. It is also known as the Crusade of Louis IX Against Tunis or the Second Crusade of Louis. The Crusade did not see any significant fighting as Louis died of dysentery shortly after arriving on the shores of Tunisia. The Treaty of Tunis was negotiated between the Crusaders and the Hafsids. No changes in territory occurred, though there were commercial and some political rights granted to the Christians. The Crusaders withdrew back to Europe soon after.

| Eighth Crusade | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Crusades | |||||||||

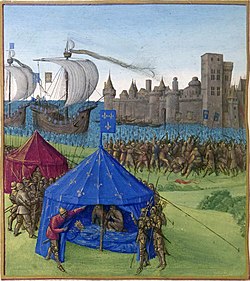

Death of Louis IX in Tunis | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Muhammad I al-Mustansir | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||||

Situation in the Holy Land

editDespite the failure of the Seventh Crusade, which ended in the capture of Louis IX of France by the Mamluks, the king did not lose interest in crusading. He continued to send financial aid and military support to the settlements in Outremer from 1254 to 1266, with the objective of eventually returning to the Holy Land.

The Kingdom of Jerusalem

editThe Seventh Crusade officially ended on 24 April 1254 with the departure of Louis IX of France from the Holy Land. He left Geoffrey of Sergines as his representative with the official post of seneschal to the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The bailli of the kingdom was John of Ibelin, succeeding his cousin John of Arsuf in 1254. John of Arsuf returned to Cyprus where he was advising Plaisance of Antioch, the regent to Hugh II of Cyprus who had claim to both kingdoms––Cyprus and Jerusalem. The death of Conrad II of Jerusalem in May 1254 had given the nominal crown of Jerusalem to his two-year-old son Conradin.[1] Prior to his departure, Louis had arranged for a truce with Damascus, to last through October 1256, reflecting the fear that an-Nasir Yusuf, the emir of Damascus and Aleppo, had of the Mongols. Because of this, he had no wish for war with the Franks. Aybak, the sultan of Egypt, also wished to avoid war and in 1255 made a ten-year truce with the Franks. Jaffa was expressly excluded from the truce, with the sultan wishing to secure it as a Palestinian port. The established frontier was hardly secure. In January 1256, the Mamluk governor of Jerusalem led an expedition in March to punish a band of Frankish raiders, he was defeated and killed. Aybak subsequently made a new treaty with Damascus that was mediated by caliph al-Musta'sim. Both Muslim leaders renewed their truces with the Franks, this time to also cover Palestine and Jaffa.[2]

Urban IV

editLatin patriarch Robert of Nantes died in 1255, having been in captivity with Louis IX during the Seventh Crusade. The new patriarch appointed by pope Alexander IV was James Pantaléon, then bishop of Verdun and later appointed as Alexander's successor, taking the name Urban IV. He was experienced in the Prussian Crusades, having helped negotiate the Treaty of Christburg in 1249. He was appointed patriarch in December 1255, and only reached Acre in the summer of 1260. Consequently, the kingdom faced the continued threats from the Muslims and Mongols, as well as internal strife, without the benefit of a senior patriarch.[3]

Conflict over Saint Sabas

editIn addition to the Muslim wars between the Mamluks and Ayyubids, and the Mongol invasions of the Levant, the Outremer states had to contend with the various Italian merchants engaged in the War of Saint Sabas. The three rival Italian cities of Genoa, Venice and Pisa maintained a presence in every Outremer seaport and from these, dominated Mediterranean trade. This commerce was equally beneficial to the Muslim emirs and both sides showed a willingness to sign treaties partially based on the fear of interrupting these sources of profit. Trouble between Pisa and Genoa had long been brewing and in 1250, a Genoese merchant was murdered by a Venetian, resulting in street fighting in Acre. When Louis finally returned home to Europe in 1254, trouble again broke out. In 1256, the commercial rivalry between the Venetian and Genoese merchant colonies erupted over possession of the monastery of Saint Sabas in Acre. The Genoese, assisted by the Pisan merchants, attacked the Venetian quarter and burned their ships, but the Venetians drove them out.[4]

The Venetians were then expelled from Tyre by Philip of Montfort. The Venetians were supported by John of Arsuf, John of Jaffa, John II of Beirut, the Knights Templar, the Teutonic Knights and the Pisans. The Knights Hospitaller supported the Genoese. In 1257, the Venetians conquered the monastery and destroyed its fortifications, although they were unable to completely expel the Genoese. The Genoese quarter was blockaded, who were then resupplied by the Hospitallers, whose complex was nearby. Philip of Montfort also sent food from Tyre. In August 1257, John of Arsuf tried to end the war by granting commercial rights in Acre to the Republic of Ancona, an Italian ally of Genoa, but aside from Philip of Montfort and the Hospitallers, the rest of the nobles continued to support Venice.[5]

Plaisance returns to Acre

editPlaisance of Cyprus was both queen of Cyprus and regent to Jerusalem. In February 1258, she and her five-year-old son, Hugh II of Cyprus, came to Tripoli to meet her brother Bohemond VI of Antioch, who escorted her to Acre. The Haute Cour of Jerusalem was convened and Bohemond asked it to confirm the claim of Hugh II as next heir after Conradin, long absent from the kingdom. It was requested that Hugh be recognized as the royal power with Plaisance as regent. Bohemond had hoped that his sister's presence would still the civil war. The Ibelins recognized the claims of Hugh and Plaisance, along with the Templars and Teutonic Knights. The Hospitallers nevertheless declared that no decision was possible in absence of Conradin. Thus the royal family was drawn into the civil war. The Venetians supported Plaisance and her son. Genoa, the Hospitallers and Philip of Montfort supported Conradin, despite the fact that they were in the past bitter opponents of Frederick II. A majority vote acknowledged Plaisance as regent. John of Arsuf resigned as bailli, only to be immediately reappointed. She and Bohemond then returned to Cyprus, instructing her bailli to act decisively against the rebels.[6]

The problems came to a head before the new Latin patriarch could arrive in Acre. While James Pantaleon had shown great ability in dealing with the Prussians, the situation in the Holy Land presented a much larger problem. He supported Plaisance, appealing to Alexander IV to take action. The pope summoned delegates from the three republics to his court at Viterbo and ordered an immediate armistice. The Venetian and Pisan diplomats were to go to Syria on a Genoese ship, and the Genoese on a Venetian ship. The envoys set out in July 1258, actually after the major conflicts had occurred. Genoa had sent a fleet under admiral Rosso della Turca, arriving off Tyre in June and there joining the deployed Genoese squadrons. On 23 June, a fleet set sail from Tyre, while Philip of Montfort's soldiers marched down the coast. The Venetians and Pisan had a smaller force under Lorenzo Tiepolo, who was not a military man and later elected Doge of Venice. The decisive Battle of Acre took place on 24 June 1258, with the Genoese retreating in disorder to Tyre. Philip's advance was halted by the Acrean militias, and the Genoese quarter within the city was overrun. Consequently, the Genoese abandoned Acre and established their headquarters at Tyre.[7]

In April 1259, the pope sent a legate to the East, Thomas Agni, then bishop of Bethlehem and later Latin patriarch, with orders to resolve the quarrel. About the same time the bailli John of Arsuf died and Plaisance came to Acre and appointed Geoffrey of Sargines as bailli. He worked with Agni to secure an armistice. In January 1261, in a meeting between the Haute Cour and delegates of the Italians, an agreement was reached. The Genoese maintained their headquarters at Tyre and the Venetians and Pisans theirs at Acre. The warring nobles and Military Orders were also reconciled. But the Italians never regarded the arrangement as final, with their war soon beginning again, to the detriment of all the commerce and the shipping along the Syrian coast, with naval skirmishes through 1270.[8]

Geoffrey of Sargines restored some semblance of order to the kingdom. His authority did not however extend into the County of Tripoli. There, Geoffrey's vassal, Henry of Jebail, was at war with Bohemond VI. Henry's cousin Bertrand Embriaco had attacked Bohemond in Tripoli itself despite the fact the Bertrand was regent to daughter Lucia of Tripoli. In 1258, the barons marched on Tripoli, laying siege to the city where Bohemond was residing. Bohemond was defeated and wounded by Bertrand and the Templars sent men to rescue him. One day, Bertrand was attacked by unknown farmers and killed. He was beheaded and his head sent as a gift to Bohemond. No one doubted that Bohemond had inspired the murder. The rebels retreated to Jebail and there was now a blood-feud between Antioch and the Embriaco family.[9]

The Byzantines recapture Constantinople

editThe inconclusive resolution of the War of Saint Sabas had implications beyond Syria. The Latin Empire of Constantinople had prospered with the help of Italian trade. Venice had holdings in both Constantinople and the Aegean islands, and so had a particular interest in the success of the empire. To counter that, Genoa actively supported Michael VIII Palaeologus, emperor of Nicaea. Michael laid the foundations for the recovery of Byzantium in 1259 by his victory at the Battle of Pelagonia where William of Villehardouin, Prince of Achaea, was captured with all his barons and obliged to cede the fortresses that dominated the eastern half of the peninsula. In March 1261, Michael signed a treaty with the Genoese, giving them preferential treatment throughout his dominions, present and future. On 25 July, with the help of the Genoese, his troops entered Constantinople. The Latin Empire, born from the Fourth Crusade, was dissolved.[10]

Regency of Cyprus and Jerusalem

editPlaisance died in September 1261. Her son Hugh II of Cyprus, then eight years old but with claims to the thrones of Cyprus and Jerusalem, required a regent. Hugh II's father Henry I of Cyprus had had two sisters. The eldest was Marie of Lusignan who had married Walter IV of Brienne, dying young and leaving a son Hugh of Brienne. The younger, Isabella of Cyprus, was married to Henry of Antioch, brother of Bohemond V of Antioch. Their son Hugh III of Cyprus, was older than his cousin, and Isabella had raised both. Hugh of Brienne, though next heir to the throne, was unwilling to compete against his aunt and her son for the regency. After some deliberation, the High Court of Cyprus appointed Hugh III as regent. The Haute Cour was given more time to consider the matter, and it was not until the spring of 1263 that Isabella came with her husband to Acre. She was accepted as regent de facto, but they refused to give her an oath of allegiance. That could only be done if Conradin were present. Geoffrey of Sargines resigned the office of bailli, which Isabella then gave to her husband, and she returned without him to Cyprus.[11]

Isabella died in Cyprus in 1264 and the regency of Jerusalem was again vacant. Hugh III of Cyprus claimed it but a counterclaim was now put in by Hugh of Brienne. He argued that the custom of France that claim of the son of an elder sister took precedence over the son of a younger, no matter which cousin was older. The jurists of Outremer rejected this argument and ruled that the decisive factor was kinship to the last holder of the office. As Isabella had been accepted as the last regent, her son Hugh III took precedence over her nephew. The nobles and high officers of state unanimously accepted him and provided the homage that had been denied to his mother. Importantly, Hugh III was recognized by Hugues de Revel and Thomas Bérard, the Grand Masters of the Hospital and the Temple. He did not appoint a formal bailli, but the government of Acre was entrusted once more to Geoffrey of Sargines.[12]

The Mongols

editThe situation in the Holy Land was complicated by the rise of the Mongols, particularly with the Mongol invasions of the Levant, beginning in the 1240s. The Mongols established the Ilkhanate in the southwestern part of their empire which served as a counterbalance to the influence of the Muslim dynasties, first defeating the Ayubbids. Their relationships with the Mamluks and the Christian West were constantly changing, serving as sometimes allies, sometimes enemies.

Louis IX and the Mongols

editLouis IX also maintained contact with the Mongol rulers of the period. During his first crusade in 1248, Louis was approached by envoys from Eljigidei, the Mongol military commander stationed in Armenia and Persia.[13] Eljigidei suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, to prevent the Egyptians and Syrians from joining forces. Louis sent the Dominican André de Longjumeau as an emissary to the Great Khan Güyük Khan in Mongolia. Güyük died before the emissary arrived at his court and no action was taken by the two parties. Instead Güyük's queen and now regent, Oghul Qaimish, politely turned down the diplomatic offer.[14] Louis dispatched another envoy to the Mongol court, the Franciscan William of Rubruck, who visited the Great Khan Möngke in Mongolia. He spent several years at the Mongol court. In 1259, Berke, the ruler of the Golden Horde, westernmost part of the Mongolian Empire, demanded the submission of Louis.[15] By contrast, Mongolian emperors Möngke and Khubilai's brother, the Ilkhan Hulagu Khan, sent a letter to the king of France seeking his military assistance, but the letter never reached France.[16]

The annihilation of the Assassins in Persia

editIn 1257, the Mongol army was in Persia, and Hulagu moved against the murderous Isma'ili sect known as the Assassins. Their ruler Rukn ad-Din Khurshah tried to avert disaster through diplomatic maneuvers. Hulagu moved deliberately through Damavand and Abbass Abad, into the Assassins' valleys. When the Mongol army approached Alamut Castle, Rukn ad-Din surrendered. The governor of the castle refused the surrender order and it was taken by force within several days. Rukn ad-Din was sent to Karakorum to meet with Möngke, who refused to see him. The two Assassin fortresses that still remained unconquered were Gerdkuh and Lambsar Castle and Rukn ad-Din was directed to arrange for their surrender. En route, he was put to death and Hulagu was ordered to exterminated the entire sect. By the end of 1257, only a few of the storied Assassins were left in the Persian mountains.[17]

The Mongols in Syria

editIn 1258, the Mongol forces under Hulagu defeated the Abbasids in the Siege of Baghdad, sacking the city following his successful campaign against the Assassins. His wife Doquz Khatun is credited with the sparing of her fellow Christians in the city.[18] Hulagu then moved on to Syria, with their invasions of the Levant. Here the Mongols were joined with their Christian allies which included Hethum I of Armenia and Bohemond VI of Antioch. The consolidated army successfully completed the Siege of Aleppo in January 1260 and then the capture of Damascus in March, led by the Nestorian Christian Kitbuqa. This effectively ended destroyed what was left of the Ayyubids. Note that the account of the triumphal ride of the Christians Kitbuqa, Hethum and Bohemond into the captured Muslim cities is questionable.[13]

Bohemond was given the port city of Lattakieh in partial exchange for the installation of the Greek patriarch Euthymius at Antioch, as the Mongols were trying to improve relations with Byzantium. For this, Bohemond earned the enmity of Acre, and he was excommunicated by the Latin patriarch of Jerusalem, James Pantaléon. When Bohemond's case was heard, Pantaléon had been elected as pope Urban IV who accepted Bohemond's explanation for his submission to the Mongols and suspended the excommunication. Euthymius was later kidnapped and taken to Armenia, replaced the Latin patriarch Opizzo Fieschi.[19]

The Mongols had no intention of engaging the Franks in battle. Nevertheless, Julian of Sidon conducted raids near Damascus, killing a Mongol commander, a nephew of Kitbuqa. In response, Sidon was sacked. John II of Beirut led a group of Templars to attack the Mongols, leading to the capture of John and Templar grand master Thomas Bérard, requiring a large ransom.[20] The Mongol capture of Damascus compelled the sultan of Egypt Qutuz to take action. Hulagu had sent envoys demanding that the sultan surrender Egypt. The envoys' heads were quickly removed and displayed on the Bab Zuweila gate of Cairo. This was followed by raids into Palestine and the apparently inevitable Mongol conquest was stalled when Hulagu, the Mongol commander in Syria, returned home after the death of his brother Möngke, leaving Kitbuqa with a small garrison. The Mamluks of Egypt then sought, and were granted, permission to advance through Frankish territory, and defeated the Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut in September 1260. Kitbuqa was killed and all of Syria fell under Mamluk control. On the way back to Egypt, Qutuz was assassinated by the general Baibars, who was far less favourable than his predecessor to alliances with the Franks.[21]

The death of Hulagu and rise of Abaqa

editHulagu died of natural causes in February 1265, weakening the Mongols' position. His widow Doquz Khatun secured the succession for her step-son Abaqa, a Buddhist who was then governor of Turkestan. Before his death, Hulagu had been negotiating with Michael VIII Palaiologos to add a daughter of the Byzantine imperial family to his large number of wives. The emperor's illegitimate daughter Maria Palaiologina was sent in 1265, escorted by Euthymius. Since Hulagu died before Maria arrived, she was instead married to Abaqa. Abaqa's transition to Ilkhan was slow, and was continually threatened by the Golden Horde, invading his territory the next spring as part of an alliance with the Mamluks. The hostilities continued until the death of Berke in 1267. Kublai Khan attempted to intervene and the new khan Möngke-Temür did not launch a major invasion into Abaqa's territory. Nevertheless, Möngke-Temür maintained the alliance with Baibars, who then felt that he could resume his campaigns against the Christians without fear of interference.[22]

Clement IV and Gregory X

editUrban IV died in October 1264 and Clement IV was elected as pope in February 1265.[23] Abaqa attempted to secure cooperation with the Western Christians against the Mamluks. Beginning in 1267, he corresponded with Clement IV and sent an ambassador to Europe in 1268, trying to form a Franco-Mongol alliance between his forces, those of the West, and those of his father-in-law Michael VIII. In 1267, the pope and James I of Aragon sent Jayme Alaric de Perpignan as an ambassador to Abaqa. In 1267, a papal letter responded positively to previous messages from the Mongols, and informed the Ilkhan of an impending Crusade:

The kings of France and Navarre, taking to heart the situation in the Holy Land, and decorated with the Holy Cross, are readying themselves to attack the enemies of the Cross. You wrote to us that you wished to join your father-in-law (the Greek emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos) to assist the Latins. We abundantly praise you for this, but we cannot tell you yet, before having asked to the rulers, what road they are planning to follow. We will transmit to them your advice, so as to enlighten their deliberations, and will inform your Magnificence, through a secure message, of what will have been decided.

— 1267 letter from Pope Clement IV to Abaqa[24]

Aqaba received responses from Rome and from James I of Aragon, though it is unclear if this was what led to James' unsuccessful expedition to Acre in 1269. Abaqa is recorded as having written to the Aragonese king, saying that he was going to send his brother, Aghai, to join the Aragonese when they arrived in Cilicia. Abaqa also sent embassies to Edward I of England. Clement IV died in 1268 and, following the longest papal election in history, was succeeded by Gregory X in September 1271.[25] In 1274, Abaqa sent a Mongol delegation to Gregory X at the Second Council of Lyons, where Abaqa's secretary Rychaldus read a report to the assembly, reminding them of Hulagu's friendliness towards Christians, and assuring them that Abaqa planned to drive the Muslims from Syria.[26]

Baibars in the Holy Land

editBaibars came to power as a military man. He was one of the commanders of the Egyptian forces that defeated the West in the Seventh Crusade and was at the vanguard of the army at Ain Jalut. This marked the first substantial defeat of the Mongol army and is regarded a turning point in history. Baibars saw the complete destruction of the Kingdom of Jerusalem as means of consolidation of power as the establishment his credentials as an Islamic ruler. He rejected the accommodating policies of his predecessors, rebuffing the numerous Frankish attempts at alliance.[27]

Ascension as sultan

editBaibars became sultan on October 1260 and quickly suppressed opposition in Egypt and Syria. However, after the conquest of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258, the Abbasid caliphate was essentially over, and the Muslim world lacked a caliph.[28] The first attempt of a new leader of the Muslims, based in Cairo, was al-Mustansir II who was killed by the Mongols in 1261 attempting to recapture Baghdad. He was replaced by al-Hakim I, beginning a dynasty that lasted until the 16th century.[29] Baibars consolidated his position by fortifying the Egyptian coastal cities and forming alliances with Michael VIII Palaiologos and Manfred of Sicily to better understand the intentions of the Europeans.[30] He also had alliances with Berke of the Kipchak Khanate and his vassal Kilij Arslan IV.[31]

Campaign in Syria and Armenia

editBaibars continued the Mamluk warring against the Crusader kingdoms in Syria. In 1263, he first began an unsuccessful siege on Acre. Abandoning this formidable target, he then turned to Nazareth, destroying all Christian buildings and declaring the city off-limits to Latin clergy. His next target resulted in the Fall of Arsuf in April 1263. After capturing the town he offered free passage to the defending Hospitallers if they surrendered their formidable citadel. Baibars' offer was accepted, but were enslaved anyway. Baibars razed the fortress to the ground. In 1265, he attacked the city and fortifications of Haifa, again razing the citadels and resulting in the Fall of Haifa. Soon after came the Fall of Caesarea.[32]

In 1266, Baibars invaded the Christian country of Cilician Armenia which Hethum I had submitted to the Mongol Empire. After defeating his forces at the Disaster of Mari, Baibars ravaged the three great cities of Mamistra, Adana and Tarsus, so that when Hetoum arrived with Mongol troops, the country was already devastated.[33] Hetoum had to negotiate the return of his son Leo II of Armenia by giving control of Armenia's border fortresses to the Mamluks. In 1269, Hetoum abdicated in favour of his son and became a monk, dying a year later. Leo was left in the awkward situation of keeping Cilicia as a subject of the Mongol Empire, while at the same time paying tribute to the Mamluks.[34]

The siege of Safed

editSafed, held by the Knights Templar, was positioned overlooking the Jordan River, allowing early warning of Muslim troop movements in the area. The fortress had been a consistent aggravation for the Muslim regional powers, and in June 1266, Baibars began the Siege of Safed, capturing it in July. Baibars had promised the Templars safe passage to Acre if they surrendered their fortress. Badly outnumbered, they agreed. Upon surrender, Baibars broke his promise as he had with the Hospitallers and massacred the entire Templar garrison. On capturing Safed, Baibars did not raze the strategically situated fortress but instead occupied and fortified it.[35] Odo of Burgundy died fighting at the same time, having led a Crusading force of fifty knights to defend the Holy Land. As early as October 1266, Clement IV would mention the fall of Safed when ordering the preaching of a new Crusade. He also arranged for a regiment of crossbowmen to be sent to the Holy Land by March 1267. The Templars' heroic defence of Safed had become legendary by the early 14th century, when it was cited at the Trial of the Knights Templars in Cyprus.[36]

The siege of Antioch

editThe loss of Cilician Armenia in 1266 isolated Antioch and Tripoli, led by Hethum's son-in-law Bohemond VI, and Baibars continued the extermination of remaining Crusader garrisons in the following years.[37] In 1268, Baibars laid siege to Jaffa, which belonged to Guy of Ibelin, the son of the jurist John of Ibelin. Jaffa fell on 7 March 1268 after twelve hours of fighting. Most of Jaffa's citizens were slain, but Baibars allowed the garrison to go unharmed. From there he proceeded to the seat of the principality and began the Siege of Antioch. The Antiochene knights and garrison were under the command of the constable of Antioch, Simon Mansel. The city was captured on 18 May 1268. Baibars had yet again promised to spare the lives of the inhabitants, but he broke his promise and had the city razed, killing or enslaving much of the population after the surrender. The loss prompted the fall of the Principality of Antioch. The massacre of men, women, and children at Antioch "was the single greatest massacre of the entire Crusading era."[38] Priests had their throats slit inside their churches, and women and children sold into slavery. As many as seventeen thousand Christians were slaughtered, and a hundred thousand dragged away into slavery.[39]

The Eighth Crusade

editAfter his victory over at Antioch, Baibars paused to assess his situation. The Mongols were restless and there were rumours of a new Crusade to be led by Louis IX. Hugh III of Cyprus asked for a truce and Baibars replied with an embassy to Acre to offer a cessation of hostilities. Bohemond VI asked to be included in the truce, but was offended when he was addressed as mere count. Nevertheless, he accepted what was offered to him. There were some minor raids into the Christian lands, but on the whole the truce was observed.[40]

Louis IX again takes the cross

editThe years after Louis IX left the Holy Land saw an escalation of the military threat posed by the Mamluks with their capturing a number of Frankish towns and fortifications and subjected Acre to frequent attack. The unthinkable––the complete loss of the kingdom––became a distinct possibility, reviving long-dormant plans for a new Crusade. The Second Barons' War was all but over with the defeat of Simon de Montfort and his rebellious barons by Edward I of England at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. The victory of Louis' brother Charles I of Anjou in the Battle of Benevento in 1266 brought the Kingdom of Sicily under Capetian control, finally freeing up French fighting forces. This encouraged Clement IV to revive the plans for a Crusade begun on 1263 under Urban IV, proclaiming a new expedition to the Holy Land in January 1266. According to the Chronica minor auctore Minorita Erphordiensi:

In the year of our Lord 1266, Pope Clement sent out letters throughout the kingdom of Germany commanding the Dominicans and Franciscans to preach the cross faithfully and urgently against the Sultan of Babylon, who is the Pharaoh of Egypt, and against the Saracens overseas, so that the suffering of the Christians [there] might be alleviated and for the support of the Holy Land.[41]

By September 1266, Louis IX had decided to take the cross once more, to lead what he hoped would be an international effort. He always hoped to set out again on a Crusade, but the needs of France were pressing. The next year, weary and ill, Louis felt able to prepare for his second Crusade and he began making the necessary arrangements, collecting the funds needed. At the Feast of the Annunciation and before the relics housed in the Sainte Chapelle, Louis IX and most of the great nobles of France once again took the cross. The date was 25 March 1267.[42]

A second ceremony took place on 5 June 1267 before a papal legate in Notre-Dame de Paris. Louis' son-in-law, Theobald II of Navarre, who had also taken the cross, was also present. The response was less enthusiastic than to his calling of the Seventh Crusade in 1248, although its unpopularity may have been exaggerated by his chronicler Jean de Joinville, who was personally opposed to the venture. Unlike Louis' first Crusade which was documented extensively by Joinville, the primary chronicler of his second Crusade was Primat of Saint-Denis. The Gestes des Chiprois and works by Guillaume de Nangis, Matthew Paris, Fidentius of Padua and al-Makrizi also form the basis of the history of the expedition.[43]

The Crusade of 1267

editThe Crusade of 1267 was a military expedition from the Upper Rhine region to the Holy Land. It was one of several minor crusades of the 1260s that resulted from a period of Papally-sponsored crusade preaching of unprecedented intensity. After Clement IV issued his bull, he ordered the German bishops, Dominicans, and Franciscans to preach the cross. The response was poor except in those regions bordering France. In the Upper Rhine however, the Crusade was preached with considerable success, resulting in several hundred Crusaders taking the cross by early 1267. The Crusaders departed from Basel during Lent 1267, under the leadership of two ministerial knights of the bishop of Basel and traveling by sea to Acre. Several of the Crusaders were able to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, but little else is known of their activity in the Holy Land; it is probable that the Germans held off from any significant military activity in expectation of the arrival of the expeditions of Louis IX of France and Edward I of England. The majority appear to have returned to Germany by 1270.[44]

The Crusade of the Infants of Aragon, 1269

editThe Mongol Ilkhan Abaqa had corresponded with James I of Aragon in early 1267, inviting him to join forces against the Mamluks. James had sent an ambassador to Abaqa in the person of Jayme Alaric de Perpignan, who returned with a Mongol embassy. Clement IV and Alfonso X of Castile tried to dissuade James from a military mission to the Holy Land, regarding him as having low moral character. However, Clement IV died in November 1268 and it was almost three years until Gregory X became the new pope, and the king of Castile had little influence in Aragon. James, who had just completed the conquest of Murcia, began collecting funds for a crusade.[45] On 1 September 1269, he sailed east from Barcelona with a powerful squadron. Immediately running into a storm. The king and most of his fleet returned home. Only a small squadron under two of the king's illegitimate sons, Pedro Fernández and Fernán Sánchez, continued the journey. They arrived at Acre at the end of December, shortly after Baibars had broken the truce, appearing at Acre with a large force. The Aragonese immediately wanted to attack the enemy, but were restrained by the Templars and Hospitallers. The Christian forces were diminished. Geoffrey of Sargines had died in April 1269 and was replaced by Robert of Cresque. His French regiment, now commanded by Olivier de Termes, was deployed on a raid beyond Montfort. The Acrean forces caught sight of the Muslim forces as they were returning. Olivier de Termes wished to slip unobserved back into Acre, but Robert of Cresque insisted on an attack. They fell into the ambush laid for them by Baibars, with few of them survived. The troops inside Acre wanted to go to their rescue, but the Aragonese restrained them. Soon afterwards they returned to Aragon, having achieved nothing.[46]

Charles I of Anjou

editThe forces of Manfred of Sicily were defeated at Benevento by Charles I of Anjou in 1266 and Manfred himself, refusing to flee, was killed in battle. Charles was lenient with Manfred's supporters, but they did not believe that this conciliatory policy could last. Clement IV censured Charles for his methods of administration, regarding him as an arrogant and obstinate. Nevertheless, Charles was asked to help oust the Ghibellines from Florence, but his expansionism towards Tuscany alarmed the pope. Clement forced Charles to promise that he would abandon all claims to Tuscany within three years. Charles pledged that he would assist Baldwin II of Courtenay in recapturing Constantinople from the Byzantine emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, in exchange for one third of the conquered lands.[47]

Charles returned to Tuscany and laid siege to the fortress of Poggibonsi, but it did not fall until the end of November 1267.[48] Some of Manfred's supporters had fled to Bavaria to attempt to persuade the 15-year-old Conradin to assert his hereditary right to Sicily. Conradin accepted their proposal and Frederick of Castile, a supporter of Manfred, was allowed by Muhammad I al-Mustansir, the Hafsid caliph of Ifiqiya (modern Tunisia), to invade Sicily from North Africa. At the Battle of Tagliacozzo on 23 August 1268, it appeared that Conradin had won the day, but, in the end, his army was routed. On 29 October 1268, Conradin and his ally Frederick of Baden were beheaded.[49] Frederick of Castile and his forces were allowed to escape to Tunis rather than being imprisoned. There they served the Tunisians in fighting against Louis' Crusaders in 1270.[50]

The preparation for the Crusade

editLouis IX never abandoned the idea of the liberation of Jerusalem, but at some point he decided to begin his new Crusade with a military campaign against Tunis. According to his confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, Louis was convinced that Muhammad I al-Mustansir was ready to convert to Christianity. The 13th-century historian Saba Malaspina believed that Charles had persuaded Louis to attack Tunis because he wanted to secure the payment of the tribute that their rulers had paid to former Sicilian monarchs. The precise motivation behind the decision is unknown, but it is believed that Louis made the choice as early as 1268.[51]

The Crusade was set to sail in early summer 1270 in ships of Genoese (19 vessels) and Marseillois (20 vessels) origin. Louis' initial plan was to descend on the coast of Outremer by way of Cyprus. However, the final plan was developed in 1269, wherein the fleet would first descend on Tunis. While Louis had limited knowledge of Africa, this objective was the only one the met the religious needs of Louis and political aims of Charles. Financing was, as usual, a challenge. Because of the lack of enthusiasm for the expedition, Louis needed to bear much of the burden. Clement IV had also ceded a tenth of the church's income in Navarre to Theobald II of Navarre to support the Crusade. The prior of Roncesvalles and the dean of Tudela were to oversee the collection of the tenth. The preaching of the Crusade in Navarre was primarily undertaken by the Franciscans and Dominicans of Pamplona.[52]

Campaign and the death of Louis IX

editOn 2 July 1270, Louis' host finally embarked from Aigues-Mortes.[53] The fleet was led by Florent de Varennes, who was the first Admiral of France, appointed in 1269. They sailed with a large, well-organized fleet, with the king stating:

"Déjà vieux, j'entreprends le voyage d'outremer. Je sacrifie pour Dieu richesse, honneurs, plaisirs... J'ai voulu vous donner ce dernier exemple et j'espère que vous le suivrez si les circonstances le commandent..."[54]

Translated, Louis told his troops that: "Already old, I begin the overseas journey. I sacrifice to God wealth, honor, pleasure. I wanted to give you this last example and I hope you will follow it if circumstances dictate."

Accompanying Louis were his brother Alphonse of Poitiers and his wife Joan of Toulouse. Also traveling with the king were his three surviving sons, Philip III of France (with his wife Isabella of Aragon), John Tristran and Peter I of Alençon, and his nephew Robert II of Artois. Also participating were Robert III of Flanders, John I of Brittany and Hugh XII de Lusignan, all sons of veterans of the previous Crusade, as well as Guy III of Saint-Pol, John II of Soissons and Raoul de Soissons.

The sailing was at least a month late. This meant that he must contend with the heat in Tunisia as well as the prospect of bad weather at sea on the second leg of the expedition, that to the Holy Land. The army was smaller than that of the Seventh Crusade. Louis' own household included 347 knights, and the total garrison was estimated at 10,000. A second fleet under Louis' son-in-law Theobald II sailed from Marseille accompanied by his wife Isabella of France, Louis' daughter.[43]

The first part of the journey was hectic. They stopped in Sardinia. The king sent Florent ahead as a scout to meet with the Sards. As their boats were Genoan, they were unwelcome. The French and Navarrene fleets joined up at Cagliari, on the southern coast of Sardinia. Here the decision to attack Tunis was announced, causing consternation among the troops as they were told they were going to Jerusalem. The high regard they had for the king reassured them.[55]

After a week at Cagliari, the force was ready and departed, quickly landing at Carthage on 18 July 1270 without serious opposition. The king sent Florent with a few men to reconnoitre the land. He found an empty harbour, with only a few Muslim and Genoan merchant ships present. The royal council was divided as to a strategy, with some thinking it was a trap, while others wanted to take advantage of the situation and disembark. The latter course was taken, and on 21 July the tower of La Goulette was seized and the army settled in the plain of Carthage. The Genoan sailors captured the fortress and, slaughtering the inhabitants, using it as their base of operations. Both sides played a waiting game, as Louis did not want to repeat his mistakes made in Egypt in 1250. He would not risk a major battle until Charles arrived. The sultan was safe behind the walls of his fortress and did not wish to engage the Franks in the open, limiting his actions to ones of harassment.[56]

The Tunisian heat, and lack of sanitation and fresh food were to doom the expedition. The Crusading force was stricken with disease, likely dysentery, with many dying. Louis IX was given last rites by Geoffrey of Beaulieu and uttered his last words, Domine in manus tuas animam meam commendavi. The king of France and leader of the Crusade died in penitence on a bed of ashes on 25 August. Philip III was the new king, but his coronation was delayed for a year.[57] As the king's death was being announced, the fleet of Charles I arrived at Tunis. After a few inconsequential skirmishes, Charles sued for peace. Muhammad I al-Mustansir, with his army similarly afflicted, was of a like mind.[56]

John II of Soissons and Raoul de Soissons died either in Tunisia or shortly after returning to France. Dying in Tunisia were Alfonso of Brienne, son of John of Brienne and a squire in the Seventh Crusade. Others, including Olivier de Termes, Raoul II of Clermont, Jean d'Eppe, Geoffrey de Geneville and John I of Brittany survived. Of the French marshals, Lancelot de Saint-Maard died, while both Raoul II Sores, and Simon de Melun survived. Of the contingent from the British Isles, Scottish nobles David Strathbogie, Earl of Atholl, died in Tunis, while Adam of Kilconquhar and Alexander de Baliol survived to fight the next year with Prince Edward.[58]

Treaty of Tunis

editThe Treaty of Tunis was signed on 1 November 1270 by Philip III of France, Charles I of Anjou and Theobald II of Navarre for the Latin Christians and Muhammad I al-Mustansir for Tunis. The treaty guaranteed a truce between the two armies. In this agreement, the Christians gained free trade with Tunis, and residence for monks and priests in the city was guaranteed. Baibars cancelled his plan to send Egyptian troops to fight the Franks in Tunis. The treaty was quite beneficial to Charles, who received one-third of a war indemnity from the Tunisians, and was promised that Hohenstaufen refugees in the sultanate would be expelled. The Crusaders left shortly thereafter and the Eighth Crusade was over.[59]

Philip III of France

editAs Count of Orléans, Philip III of France accompanied his father to Tunis. Louis IX had entrusted the kingdom to Mathieu de Vendôme and Simon II of Clermont, to whom he had also given the royal seal. The epidemic that took Louis spared neither Philip nor his family. His brother John Tristan died first, on 3 August, and on 25 August the king died. To prevent putrefaction of his remains, it was decided to carry out mos Teutonicus, the process of rendering the flesh from the bones so as to make transporting the remains feasible.[60]

Philip III, only 25 years old and stricken with disease, was proclaimed king in Tunisia. He was party to the treaty between the kings of France, Sicily and Navarre and the caliph of Tunis. Other deaths followed this debacle. In December 1270, Philip's brother-in-law, Theobald II of Navarre, died. He was followed in February by Philip's wife, Isabella, who fell off her horse while pregnant with their fifth child. In April, Theobald's widow and Philip's sister Isabella also died. Philip III arrived in Paris on 21 May 1271, and paid tribute to the deceased. The next day the funeral of his father was held. The new sovereign was crowned king of France in Reims on 15 August 1271.[61]

Aftermath

editEdward arrived with an English fleet the day before the Crusaders left Tunis. The English returned to Sicily with the rest of Louis' force. On 22 November the combined fleet was destroyed in a storm off Trapani. At the end of April 1271, the English continued to Acre to carry on Lord Edward's Crusade. It was to be the last of the great crusades to the Holy Land.[62]

On 1 September 1271, Gregory X was finally elected pope. The election took place while he was engaged at Acre with Edward's expedition. Not wanting to abandon his mission, his first action upon hearing of his election, was to send out appeals for aid to the Crusaders. At his final sermon at Acre just before setting sail for Italy, he famously remarked, quoting Psalm 137, "If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning". He was consecrated on 27 March 1272 at St. Peter's Basilica.[63]

On 31 March 1272, the Second Council of Lyons convened. The council approved plans for passagium generale to recover the Holy Land, which was to be financed by a tithe imposed for six years on all the benefices of Christendom. James I of Aragon wished to organize the expedition at once, but this was opposed by the Knights Templar. The Franciscan friar Fidentius of Padua, who had experience in the Holy Land, was commissioned by the pope to write a report on the recovery of the Holy Land.[64]

Abaqa sent a Mongol delegation to the council where his secretary Rychaldus read a report to the assembly, reminding them of Hulagu's friendliness towards Christians, and assuring them that the Ilkhan planned to drive the Muslims from Syria. Gregory then promulgated a new Crusade to start in 1278 in conjunction with the Mongols. The pope's death in 1276 put an end to any such plans, and the money that had been gathered was instead distributed in Italy.[65]

Philip III launched the unfortunate Aragonese Crusade in 1284.[66] Like his father before him, he died of dysentery, on 5 October 1285, and was succeeded by his son Philip IV of France. Philip IV would oversee the final loss of the Holy Land after the Siege of Acre in 1291.[67]

Participants

editA partial list of those that participated in the Eighth Crusade can be found in the category collections of Christians of the Eighth Crusade and Muslims of the Eighth Crusade.

Literary response

editBertran d'Alamanon, a diplomat in the service of Charles of Anjou, and Ricaut Bono criticised the papal policy of pursuing wars in Italy with money that should have gone overseas. The failure of the Eighth Crusade, like those of its predecessors, caused a response to be crafted in Occitan poetry by the troubadours. The death of Louis IX of France especially sparked their creative output, notable considering the hostility which the troubadours had previously shown towards the French monarchy during the Albigensian Crusade. Three planhs, songs of lament, were composed for the death of Louis IX.

Guilhem d'Autpol composed Fortz tristors es e salvaj'a retraire for Louis. Raimon Gaucelm de Bezers composed Qui vol aver complida amistansa to celebrate the preparations of the Crusade in 1268, but in 1270 he had to compose Ab grans trebalhs et ab grans marrimens in commemoration of the French king. Austorc de Segret composed No sai quim so, tan sui desconoissens, a more general Crusading song, that laments Louis but also that either God or Satan is misleading Christians. He also attacks Louis' brother Charles, whom he calls the caps e guitz (head and guide) of the infidels, because he convinced Louis to attack Tunis and not the Holy Land, and he immediately negotiated a peace with the Muslims after Louis' death.

After the Crusade, the aged troubadour Peire Cardenal wrote a song, Totz lo mons es vestitiz et abrazatz (more or less: the entire world is besieged and surrounded [by falsehood]), encouraging Louis' heir, Philip III, to go to the Holy Land to aid Edward Longshanks.

Satiric verses were composed in Tunis about Louis' new plan to invade Tunis: "O Louis, Tunis is the sister of Egypt! thus expect your ordeal! you will find your tomb here instead of the house of Ibn Lokman; and the eunuch Sobih will be here replaced by Munkir and Nakir.".[68]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Conradin". Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 968–969.

- ^ Gibb 1969, pp. 712–714, The Ayyubids and the Mamluks.

- ^ Douglas Raymund Webster (1912). "Pope Urban IV". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Marshall 1994, pp. 217–231, Sieges.

- ^ Runciman 1969, pp. 568–570, The War of Saint Sabas.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 284–285, Queen Plaisance at Acre (1258).

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 285–286, The Battle of Acre, 1258.

- ^ Richard 1979, pp. 364–406, The war of St Sabas.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 287–288, Bohemond in Tripoli.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 286–287, The Byzantines Recapture Constantinople.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 288–289, Hugh of Cyprus, Regent of Jerusalem.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 289–290, Hugh III of Cyprus.

- ^ a b Jackson, Peter (1980). “The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260”. The English Historical Review, Vol. 95, No. 376, Oxford University Press, pp. 481–513.

- ^ Grousset 1970, pp. 272–274, Regency of Orhul Qaimish.

- ^ Sinor, Denis (1999). "The Mongols in the West". Journal of Asian History, Vol. 33, No. 1, Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 1–44.

- ^ Aigle, Denise (2005). "The Letters of Eljigidei, H¨uleg¨u and Abaqa: Mongol overtures or Christian Ventriloquism?". Inner Asia. 7 (2): 143–162.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 300–302, Annihilalation of the Assassins in Persia, 1257.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 302–303, The Mongols sack Baghdad.

- ^ Richard 1999, pp. 423–426, The Crusade and the Mongols.

- ^ Marshall 1994, pp. 176–187, Raiding Expeditions.

- ^ Runciman 1969, pp. 571–575, The Mongols.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 318–319, Death of Hulagu.

- ^ William Walker Rockwell (1911). "Clement IV". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 483–484.

- ^ Grousset 1934, p. 644, Volume 3, Clement IV and Abaqa.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gregory X". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 574.

- ^ Cahen 1969, pp. 722–723, Abagha.

- ^ Ziyādaẗ 1969, pp. 747–750, Baybars.

- ^ Holt, P. M. “Some Observations on the ’Abbāsid Caliphate of Cairo.” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 47, no. 3, 1984, pp. 501–507.

- ^ Bosworth 2004, pp. 7–10, The Caliphs in Cairo, 659–923/1261–1517.

- ^ Pahlitzsch 2006, pp. 156–158, Baybars I.

- ^ Holt 1995, pp. 11–22, Mamluk–Frankish diplomatic relations.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 316–318, Baibars in Palestine.

- ^ Chahin 2001, pp. 242–258, The Kingdom of Armenia in Cilicia.

- ^ Stewart 2001, The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks.

- ^ Shachar, Uri Zvi (2020). "Enshrined Fortification: A Trialogue on the Rise and Fall of Safed". The Medieval History Journal. 23 (2): 265–290. doi:10.1177/0971945819895898. S2CID 212846031.

- ^ Marshall 1994, pp. 217–249, Siege of Safed.

- ^ Bouchier 1921, pp. 268–270, Invasion of Sultan Baibars.

- ^ Madden 2005, p. 168, Siege of Antioch.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 324–325, The Fall of Antioch, 1268.

- ^ Madden 2010, pp. 173–194, Louis IX, Charles of Anjou and the Tunis Crusade of 1270.

- ^ Morton, Nicholas (2011). "In subsidium: The Declining Contribution of Germany and Eastern Europe to the Crusades to the Holy Land, 1221–1291". German Historical Institute London Bulletin. 33 (1): 38–66

- ^ Strayer 1969, pp. 508–518, The Crusade of Louis IX to Tunis.

- ^ a b Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 207–212, The Second Crusade of Louis.

- ^ Bleck, Reinhard, “Ein oberrheinischer Palästina-Kreuzzug 1267” Basler Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Altertumskunde 87 (1987), pp. 5–27.

- ^ Chaytor 1933, pp. 90–96, The Crusade of James I of Aragon.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 330–331, The Crusades of the Infants of Aragon.

- ^ Abulafia, David, “Charles of Anjou Reassessed,” Journal of Medieval History 26 (2000), 93–114.

- ^ Runciman 1958, p. 101, The fortress of Poggibonsi.

- ^ James Francis Loughlin (1908). "Pope Clement IV". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 326–327, Hugh, King of Cyprus and Jerusalem.

- ^ Strayer 1969, pp. 512–513, Louis' decision to attack Tunis.

- ^ Cazel 1969, pp. 116–149, Financing the Crusades.

- ^ Lower 2018, pp. 100–122, The Crusade Begins.

- ^ Florent de Varennes. Net-Marine

- ^ Runciman 1954, pp. 290–292, Louis's Last Crusade.

- ^ a b Strayer 1969, pp. 513–515, Louis' Crusade to Tunis.

- ^ Archer 1904, pp. 402–403, Death of St. Louis.

- ^ Bruce Beebe, The English Baronage and the Crusade of 1270. Bulletin of the Institute of Historical Research, Volume 48, Issue 118, November 1975. pp. 127–148.

- ^ Lower 2018, pp. 123–143, The Peace of Tunis.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Philip III, King of France. Encyclopædia Britannica. 21 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 381.

- ^ Kitchin 1892, pp. 358–367, Philip III, A.D. 1270–1285.

- ^ Summerson, Henry (2005). Lord Edward's crusade (act. 1270–1274). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ Johann Peter Kirsch (1908). "Pope Gregory X". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Pierre-Louis-Théophile-Georges Goyau (1910). "Second Council of Lyons (1274)". In Catholic Encyclopedia. 4. New York.

- ^ Second Council of Lyons 1274. Papal Encyclicals Online, 2020.

- ^ Strayer, J. R. “The Crusade against Aragon.” Speculum, Vol. 28, No. 1, 1953, pp. 102–113.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Philip IV, King of France. Encyclopædia Britannica. 21(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 381–382.

- ^ Verses by a contemporary Tunesian named Ahmad Ismail Alzayat (Al-Maqrizi, p. 462/vol. 1) – House of Ibn Lokman was the house in al-Mansurah where Louis was imprisoned in chains after he was captured in Fariskur during the Seventh Crusade and where he was under the guard of a eunuch named Sobih. According to Muslim creed Munkir and Nakir are two angels who interrogate the dead.

Bibliography

edit- Archer, Thomas Andrew (1904). The Crusades: The Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Story of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Putnam.

- Asbridge, Thomas (2012). The Crusades: The War for the Holy Land. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1849836883.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). The New Islamic dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748621378.

- Bouchier, Edmund Spenser (1921). A Short History of Antioch, 300 B.C. – A.D. 1268. B. Blackwell, Oxford.

- Cahen, Claude (1969). The Mongols and the Near East (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume IIf.

- Carolus-Barré, Louis (1976). Septième centenaire de la mort de Saint Louis. Actes des Colloques de Royaumont et de Paris.

- Cazel, Fred A. Jr. (1969). Financing the Crusades (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume VI.

- Chahin, Mack (2001). The Kingdom of Armenia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0700714520.

- Chaytor, Henry John (1933). A History of Aragon and Catalonia. Methuen. ISBN 978-0404014797.

- Dawson, Christopher (1955). The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Sheed and Ward. ISBN 978-0758139252.

- Furber, Elizabeth Chapin (1969). The Kingdom of Cyprus, 1191–1291 (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1969). The Aiyūbids (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Grousset, René (1934). Histoire des croisades et du royaume franc de Jérusalem. Plon, Paris.

- Grousset, René (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia. Translated by Naomi Walford. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813513041.

- Hardwicke, Mary Nickerson (1969). The Crusader States, 1192–1243 (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Holt, Peter Malcom (1995). Early Mamluk Diplomacy, 1260–1290: Treaties of Baybars and Qalāwūn with Christian Rulers. E. J. Brill, New York. ISBN 978-9004102460.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen (1977). From Saladin to the Mongols: The Ayyubids of Damascus, 1193–1260. State University of New York. ISBN 978-0873952637.

- Irwin, Robert (1986). The Middle East in the Middle Ages: The Early Mamluk Sultanate, 1250–1382. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-1597400480.

- Jordan, William (1979). Louis IX and the Challenge of the Crusade: A Study in Rulership. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691635453.

- Kitchin, George W. (1892). A History of France. Clarendon Press series. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1901). History of Egypt in the Middle Ages. A History of Egypt; v. 6. Methuen, London. ISBN 978-0790532042.

- Lapina, Elizabeth (2017). "Crusades, Memory and Visual Culture: Representations of the Miracle of Intervention of Saints in Battle". In Megan Cassidy-Welch (ed.). Remembering the Crusades and Crusading. Routledge. pp. 49–72.

- Lock, Peter (2006). The Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203389638. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.

- Lower, Michael (2018). The Tunis Crusade of 1270: A Mediterranean History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198744320.

- Maalouf, Amin (2006). The Crusades through Arab Eyes. Saqi Books. ISBN 978-0863560231.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2005). The New Concise History of the Crusades. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0742538221.

- Madden, Thomas F. (2010). Crusades: Medieval Worlds in Conflict. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1138383937.

- Maier, Christoph T. (1998). Preaching the Crusades: Mendicant Friars and the Cross in the Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521638739.

- Marshall, Christopher (1994). Warfare in the Latin East, 1192–1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521477420.

- Murray, Alan V. (2006). The Crusades – An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1576078624.

- Norwich, J.J. (1995). Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. Penguin, London. ISBN 978-0670823772.

- Oman, Charles (1924). A History of the Art of War in the Middle Ages. Metheun.

- Pahlitzsch, Johannes (2006). Baybars I (d. 1277). The Crusades – An Encyclopedia.

- Paterson, Linda (2003). Lyric allusions to the Crusades and the Holy Land. Colston Symposium.

- Perry, Guy (2018). The Briennes: The Rise and Fall of a Champenois Dynasty in the Age of the Crusades, c. 950–1356. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107196902.

- Phillips, Jonathan (2009). Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades. Random House. ISBN 978-0224079372.

- Richard, Jean C. (1979). The Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Amsterdam, North Holland. ISBN 978-0444852625.

- Richard, Jean C. (1992). Saint Louis, Crusader King of France. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521381567.

- Richard, Jean C. (1999). The Crusades, c. 1071 – c. 1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521625661.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1973). The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174–1277. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0333063798.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300101287.

- Roux, Jean-Paul (1993). Histoire de l'Empire mongol. Fayard. ISBN 978-2213031644.

- Runciman, Steven (1954). A History of the Crusades, Volume Three: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521347723.

- Runciman, Steven (1958). The Sicilian Vespers: A History of the Mediterranean World in the Later Thirteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107604742.

- Runciman, Steven (1969). The Crusader States, 1243–11291 (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1969). A History of the Crusades. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Smith, Caroline (2006). Crusading in the Age of Joinville. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0754653639.

- Stewart, Angus Donal (2001). The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks. Brill. ISBN 978-9004122925.

- Strayer, Joseph (1969). The Crusades of Louis IX (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Tyerman, Christopher (1996). England and the Crusades, 1095–1588. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226820122.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0674023871.

- Whalen, Brett Edward (2019). The Two Powers: The Papacy, the Empire, and the Struggle for Sovereignty in the Thirteenth Century. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812250862.

- Wolff, Robert Lee (1969). The Latin Empire of Constantinople, 1204–1312 (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.

- Ziyādaẗ, Muḥammad Muṣṭafā (1969). The Mamluk Sultans to 1293 (PDF). A History of the Crusades (Setton), Volume II.