History of African Americans in Baltimore

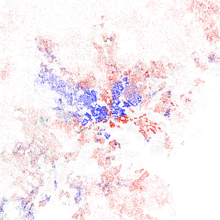

The history of African Americans in Baltimore dates back to the 17th century when the first African slaves were being brought to the Province of Maryland. Majority white for most of its history, Baltimore transitioned to having a black majority in the 1970s.[2] As of the 2010 Census, African Americans are the majority population of Baltimore at 63% of the population. As a majority black city for the last several decades with the 5th largest population of African Americans of any city in the United States, African Americans have had an enormous impact on the culture, dialect, history, politics, and music of the city. Unlike many other Northern cities whose African-American populations first became well-established during the Great Migration, Baltimore has a deeply rooted African-American heritage, being home to the largest population of free black people half a century before the Emancipation Proclamation. The migrations of Southern and Appalachian African Americans between 1910 and 1970 brought thousands of African Americans to Baltimore, transforming the city into the second northernmost majority-black city in the United States after Detroit. The city's African-American community is centered in West Baltimore and East Baltimore. The distribution of African Americans on both the West and the East sides of Baltimore is sometimes called "The Black Butterfly", while the distribution of white Americans in Central and Southeast Baltimore is called "The White L."[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 375,002[1] (2020) |

Demographics

edit| African-American population in Baltimore | |

|---|---|

| Year | Percentage |

| 1790 | 11.7% |

| 1800 | 21.2% |

| 1810 | 22.2% |

| 1820 | 23.4% |

| 1830 | 23.5% |

| 1840 | 20.7% |

| 1850 | 16.8% |

| 1860 | 13.1% |

| 1870 | 14.8% |

| 1880 | 16.2% |

| 1890 | 15.4% |

| 1900 | 15.6% |

| 1910 | 15.2% |

| 1920 | 14.8% |

| 1930 | 17.7% |

| 1940 | 19.3% |

| 1950 | 23.8% |

| 1960 | 34.7% |

| 1970 | 46.4% |

| 1980 | 54.8% |

| 1990 | 59.2% |

| 2000 | 64.3% |

| 2010 | 63.7% |

| 2020 | 62.4% |

In the 1790 census, the first census in the history of the United States, African American constituted 11.7% of Baltimore's population. 1,578 lived in Baltimore in that year.[4] From 1800 until 1840, African Americans were between a fifth and a quarter of Baltimore's population. The African-American population decreased in the 1850s to around 17%. The lowest percentage for African Americans in Baltimore was in 1860, constituting 13% of the population. Between the 1860s and the 1920s, Baltimore's African-American population remained between 13-16% of the population. The proportion only began to increase again in the 1930s and 1940s, during the Great Migration.[4] During the Great Migration, thousands of African Americans from the Southern United States moved to Baltimore in search of better socioeconomic conditions and freedom from segregationist Jim Crow laws, lynching, and other forms of anti-black racism. Baltimore was a major destination for Southern and Appalachian African Americans, with many coming from the states of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina.[5]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 325,589 African-American residents, 34.7% of Baltimore's population.[6] By 1970 Africans Americans were 46.4% of Baltimore's population, on the verge of becoming the majority for the first time.[4]

In the 1980 United States Census, there were 431,151 African Americans living in Baltimore, constituting 54.8% of the population. The 1980 census was the first census for which African Americans were a majority in Baltimore.[7] By the 1990 United States Census, there were 435,768 African Americans, constituting 59.2% of the population.[7]

The Black or African-American community in the Baltimore metropolitan area numbered 699,962 as of 2000, making up 27.4% of the area's population.[8]

In the 2010 United States Census, there were 395,781 African Americans living in Baltimore, constituting 63.7% of the population.[9]

In 2017, an estimated 389,222 African Americans resided in Baltimore city, 62.8% of the population.[10]

Baltimore's African-American population has been declining in numbers each year since 1993, while the white population has been increasing during the 2010s. The black population has decreased due to a combination of black flight, an influx of younger whites, gentrification, and immigration of Latinos and Asians.[11]

Many black Baltimore residents have moved to the suburbs or returning to Southern cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, Houston, Birmingham, Memphis, San Antonio and Jackson.[12][13]

History

edit17th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

The first black people to reside in what is now Baltimore city came in 1634 under Lord Baltimore's charter alongside the Englishmen, only fifteen years after the first Africans arrived in the Colony of Virginia in 1619. A Jesuit missionary named Andrew White brought two mixed-race indentured servants named Mathias de Sousa and Francisco. The brothers Frederick and Edward Wintour brought a enslaved african named John Prince.[14]

18th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

19th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

The first annual conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church was held in Baltimore in 1817.[15]

From the late 18th century into the 1820s Baltimore was a "city of transients," a fast-growing boom town attracting thousands of ex-slaves from the surrounding countryside. Slavery in Maryland declined steadily after the 1810s as the state's economy shifted away from plantation agriculture, as evangelicalism and a liberal manumission law encouraged slaveholders to free enslaved people held in bondage, and as other slaveholders practiced "term slavery," registering deeds of manumission but postponing the actual date of freedom for a decade or more. Baltimore's shrinking population of enslaved people often lived and worked alongside the city's growing free black population as "quasi-freedmen." With unskilled and semiskilled employment readily available in the shipyards and related industries, little friction with white workers occurred. Despite the overall poverty of the city's free black people, compared with the condition of those living in Philadelphia, Charleston, and New Orleans, Baltimore was a "city of refuge," where enslaved and free black people alike found an unusual amount of freedom. Churches, schools, and fraternal and benevolent associations provided a cushion against hardening white attitudes toward free people of color in the wake of Nat Turner's revolt in Virginia in 1831. But a flood of German and Irish immigrants swamped Baltimore's labor market after 1840, driving free black people deeper into poverty.[16]

The Maryland Chemical Works of Baltimore used a mix of free labor, hired slave labor, and enslaved people held by the corporation to work in its factory.[17] Since chemicals needed constant attention, the rapid turnover of free white labor encouraged the owner to use enslaved workers. While slave labor was about 20 percent cheaper, the company began to reduce its dependence on enslaved labor in 1829 when two slaves ran away and one died.[18]

The location of Baltimore in a border state created opportunities for enslaved people in the city to run away and find freedom in the north—as Frederick Douglass did. Therefore, slaveholders in Baltimore frequently turned to gradual manumission as a means to secure dependable and productive labor from slaves. In promising freedom after a fixed period of years, slaveholders intended to reduce the costs associated with lifetime servitude while providing slaves incentive for cooperation. Enslaved people tried to negotiate terms of manumission that were more advantageous, and the implicit threat of flight weighed significantly in slaveholders' calculations. The dramatic decrease in the enslaved population during 1850-60 indicates that slavery was no longer profitable in the city. Slaves were still used as expensive house servants: it was cheaper to hire a free worker by the day, with the option of dropping him or replacing him with a better worker, rather than run the expense of maintaining a slave month in and month out with little flexibility.[19]

On the eve of the Civil War, Baltimore had the largest free black community in the nation. About 15 schools for black people were operating, including Sabbath schools operated by Methodists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, along with several private academies. All black schools were self-sustaining, receiving no state or local government funds, and whites in Baltimore generally opposed educating the black population, continuing to tax black property holders to maintain schools from which black children were excluded by law. Baltimore's black community, nevertheless, was one of the largest and most divided in America due to this experience.[20]

Civil War period

editMaryland was not subject to Reconstruction, but the end of slavery meant heightened racial tensions as free black people flocked to the city and many armed confrontations erupted between black people and whites. Rural black people who flocked to Baltimore created increased competition for skilled jobs and upset the prewar relationship between free black people and whites. As black migrants were relegated to unskilled work or no work at all, violent strikes erupted. Denied entry into the regular state militia, armed black people formed militias of their own. In the midst of this change, white Baltimoreans interpreted black discontent as disrespect for law and order, which justified police repression.[21]

Baltimore had a larger population of African Americans than any northern city. The new Maryland state constitution of 1864 ended slavery and provided for the education of all children, including black people. The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People established schools for black people that were taken over by the public school system, which then restricted education for black people beginning in 1867 when Democrats regained control of the city. Establishing an unequal system that prepared white students for citizenship while using education to reinforce black subjugation, Baltimore's postwar school system exposed the contradictions of race, education, and republicanism in an age when African Americans struggled to realize the ostensible freedoms gained by emancipation.[22] Thus black people found themselves forced to support Jim Crow legislation and urged that the "colored schools" be staffed only with black teachers. From 1867 to 1900 black schools grew from 10 to 27 and enrollment from 901 to 9,383. The Mechanical and Industrial Association achieved success only in 1892 with the opening of the Colored Manual Training School. Black leaders were convinced by the Rev. William Alexander and his newspaper, the Afro American, that economic advancement and first-class citizenship depended on equal access to schools.[20]

20th century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

After the supreme court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional in 1883[23] and the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Supreme court case upheld the principle of "separate but equal",[24] Maryland passed a series of legislation that segregated the state by race. Starting in 1902, Democratic legislators proposed a bill to segregate transportation, but the combined efforts of railroad and steamship companies and over one thousand opposing citizens defeated the bill. Two years later, however, Maryland passed a law requiring railroad companies to operate separate cars and coaches for white and colored passengers.[25] Segregation laws were extended to steamboats in 1908, outlawing people of color from sharing the same restrooms and sleeping quarters as white people.[26]

With the upswell of urbanization and industrialization, Baltimore experienced a boom in population, with its African American population growing from 54,000 to 79,000 between 1880 and 1900 and its total population more than doubling from 250,000 to 509,000 between 1870 and 1900.[27] At the turn of the century, Baltimore citizens were also grappling with the escalation of disease and economic depression. African Americans moving from the South and rural areas with little money and limited job opportunities compromised living conditions by seeking cheaper housing and sharing apartments designed for single-families across multiple large families. This influx of residents into neighborhoods with poor sanitation and structural integrity began the formation of Baltimore's first slums.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Baltimore citizens had experienced no legislation segregating their housing. However, white residents became hostile towards black citizens moving from rural areas and the Baltimore slums into predominantly white neighborhoods, leading lawyer Milton Dashiell to draft an ordinance to segregate Baltimore. Milton Dashiell advocated for an ordinance to bar African Americans from moving into the Eutaw Place neighborhood in northwest Baltimore. He proposed to recognize majority white residential blocks and majority black residential blocks, and to prevent people from moving into housing on such blocks where they would be a minority. The Baltimore Council passed the ordinance, and it became law on December 20, 1910, with Democratic Mayor J. Barry Mahool's signature, cementing Baltimore as the first U.S. city to pass a residential segregation ordinance.[28] The Baltimore segregation ordinance was the first of its kind in the United States. Many other southern cities followed with their own segregation ordinances, though the US Supreme Court ruled against them in Buchanan v. Warley (1917).[29] [30]

Although Baltimore had experienced an influx in its African American population around the turn of the century, the start of the First World War and the increased availability of urban industry jobs spurred the Great Migration, leading Baltimore like other Northern cities to experience a surge in its African American population, particularly around its ports. In response to the 1917 supreme court decision that abolished residential segregation and the influx of African American migrants, Mayor James H. Preston ordered housing inspectors to report anyone who rented or sold property to black people in predominantly white neighborhoods.[31] This order entrenched the geographical divide by race in Baltimore, laying the redline foundations in the city. Twenty years later, Baltimore's housing projects were racially segregated into "white housing" and "Negro housing", further discriminating the distribution of Baltimore's resources.

By 1968, Baltimore was home to a local chapter of the Black Panther Party. The Black Panther Party struggled in Baltimore during the late 1960s and early 1970s due to campaigns of surveillance and harassment from the FBI and the Baltimore City Police Department. Between 1968 and 1972, the Baltimore Black Panthers used a number of different buildings to house meetings and other activities. Over a period of four years, the Party organized community activities and classes and conducted dozens of protests. The Party was initially organized informally at the Soul School on 522 North Fremont Avenue near the George P. Murphy Homes. The first formal headquarters for the Party was at a private residence at 1209 North Eden Street. Party members organized free breakfast and lunch programs at the St. Martin de Porres Recreation Hall at the former St. John the Evangelist Catholic Church (a building which is now home to Sweet Prospect Baptist Church). By 1970 the Black Panther Party headquarters was known as the "Black Community Information Center" and have moved into a rented residence at 1248 N. Gay Street. The largely white Baltimore Committee for Political Freedom was created due to fears that Baltimore police were planning to assassinate Black Panther Party leaders in Baltimore, with Reverend Chester Wickwire and the sociologist Peter H. Rossi playing a prominent role.[32]

21st century

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2019) |

On April 12, 2015, outrage over the Death of Freddie Gray while under the custody of Baltimore Police Department officers lead to the 2015 Baltimore protests. On April 19, 2015, West Baltimore resident Freddie Gray died after being in a coma for a week. Gray, who had a record of arrests for petty criminal activity, had been taken into custody after running from police. Gray suffered spinal injuries while in police custody and fell into the coma. The cause of his injuries was disputed, with some claiming they were accidental, while others claiming they were the result of police brutality. Protests were initially nonviolent, with thousands of peaceful protesters filled the City Hall square. Protests against police brutality turned violent following Gray's funeral on April 27, as people burned police cruisers and buildings and damaged shops. The Governor of Maryland, Larry Hogan sent in the National Guard and imposed a curfew.[33] Six police officers were charged with crimes relating to Gray's death. One was acquitted, one trial ended in a hung jury, and four cases are on going as of June 12, 2016.[citation needed]

Culture

editDialect

editAccording to linguists, the accent and dialect of African American Baltimoreans are different from the "hon" variety that is popularized in the media as being spoken by white blue-collar Baltimoreans.[34] White working-class families who migrated out of Baltimore city along the Maryland Route 140 and Maryland Route 26 corridors brought local pronunciations with them, creating colloquialisms that make up the Baltimore accent, cementing the image of "Bawlmerese" as the "Baltimore accent". This white working-class dialect is not the only "Baltimore accent", as Black Baltimoreans have their own unique accent. For example, among Black speakers, Baltimore is pronounced more like "Baldamore," as compared to "Bawlmer." Other notable phonological characteristics include vowel centralization before /r/ (such that words such as "carry" and "parents" are often pronounced as "curry" or "purrents") and the mid-centralization of /ɑ/, particularly in the word "dog," often pronounced like "dug," and "frog," as "frug."[35] The accent and dialect of African-American Baltimoreans also share features of African American English.[35]

LGBT community

editIn 2001, The Portal was established as a community center for LGBT African-Americans.[36] The now-defunct center was intended as a safe place for LGBT people of color and offered health and safety information including AIDS awareness.[37] The Portal's goal was to promote "stronger, more effective same gender loving communities of color through access to quality healthcare and economic and educational services" and they served men who have sex with men as well as women who have sex with women.[38][39]

Many black bisexual and black gay men in Baltimore are "on the down low." Men who are "down-low" identify as heterosexual, but also have sex with men. This is often due to homophobia in the African-American community. The taboo on acknowledging homosexuality and bisexuality can contribute to issues of infidelity and higher rates of HIV/AIDS. Black bisexual men may conceal their bisexuality while projecting an image of machismo. As part of his research into the "down-low" phenomena for his 2004 book On the Down Low, gay African-American author and HIV/AIDS activist J. L. King interviewed 2,500 men on the down-low, many of them from Baltimore.[40]

The Unity Fellowship Church of Baltimore, headed by Reverend Harris Thomas, is a church that serves LGBT African-American Christians and other LGBT Christians of color. Unity Fellowship is the local branch of a national movement that caters to LGBT Christians of color. Baltimore's Unity Fellowship Church is located on Old York Road and has a congregation of around 150 people. While homophobia exists within the African-American community, the majority of African Americans in Maryland are supportive of same-sex marriage.[41]

Club Bunns, a gay club near Lexington Market that attracted a gay black male clientele, closed in February 2019 after 30 years in business.[42]

Literature

editIn the 1930s and 1940s, the Communist Party of Maryland ran a communist bookstore called the Frederick Douglass Bookshop, which was frequently monitored by FBI agents and informants. The Frederick Douglass Bookshop was described by the FBI as a “Communist Party literature distribution point in the Negro section of [West] Baltimore.” For a decade this black communist bookstore served as a central meeting place for Baltimore's Communist Party, hosting meetings for party officials and new members.[43]

William Paul Coates (father of Ta-Nehisi Coates) founded Black Classic Press (BCP) in 1978 in Baltimore, originally working from the basement of his house.[44][45] The company is one of the oldest independently owned Black publishers in operation in the United States.[46] BCP has published original titles by notable authors including Walter Mosley, John Henrik Clarke, E. Ethelbert Miller, Yosef Ben-Jochannan, and Dorothy B. Porter, as well as reissuing significant works by Amiri Baraka, Larry Neal, W. E. B. Du Bois, Edward Blyden, Bobby Seale, J. A. Rogers, and others.

Media

editThe Baltimore Afro-American, commonly known as The Afro, is a weekly newspaper published in the city. It is the flagship newspaper of the Afro-American chain and the longest-running African-American family-owned newspaper in the United States, established in 1892 by John H. Murphy Sr.[47][48]

Museums

editThe Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture is the premier experience and best resource for information and inspiration about the lives of African American Marylanders. The Lewis Museum's mission is to collect, preserve, interpret, document, and exhibit the rich contributions of African American Marylanders using its collection of over 11,000 documents and objects and resources drawn from across the country. The 82,000 square foot museum is located an easy two-block walk from Baltimore's Inner Harbor at 830 E. Pratt Street. Opened in 2005, the museum is an affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, and was named after Reginald F. Lewis, the first African American to build a billion-dollar company, TLC Beatrice International Holdings.[49]

The National Great Blacks In Wax Museum is a wax museum located in the neighborhood of Oliver that features prominent African-American historical figures. It was established in 1983, in a downtown storefront on Saratoga Street. The museum is currently located on 1601 East North Avenue in a renovated firehouse, a Victorian Mansion, and two former apartment dwellings that provide nearly 30,000 square feet (3,000 m2) of exhibit and office space. The exhibits feature over 100 wax figures and scenes, a full model slave ship exhibit which portrays the 400-year history of the Atlantic Slave Trade, an exhibit on the role of youth in making history, and a Maryland room highlighting the contributions to African American history by notable Marylanders.[50]

Theatre and cinema

editThe Royal Theatre, located at 1329 Pennsylvania Avenue in Baltimore, Maryland, first opened in 1922 as the black-owned Douglass Theatre. It was the most famous theater along West Baltimore City's Pennsylvania Avenue, one of a circuit of five such theaters for black entertainment in big cities. Its sister theaters were the Apollo in Harlem, the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C., the Regal Theatre in Chicago, and the Earl Theater in Philadelphia.[51] As middle-class, white flight from Old West Baltimore continued during the 1960s and 1970s and accelerated after Pennsylvania Avenue was damaged during the civil rights riots, the entire community began a period of long decline. In 1971, the Royal Theater was demolished.[51]

The subject of young African-American dirt bike riders in Baltimore has been the subject of two documentaries and one fictional film. Debuting in 2001, 12 O'Clock Boyz was the first film to documentary the dirt bike scene in the city. In 2013, another documentary titled 12 O'Clock Boys was made focusing on the same subject of urban dirt bike culture.[52] The film Charm City Kings, starring Teyonah Parris and Meek Mill, is a feature film adaptation of the 2013 12 O'Clock Boys documentary.[53]

Religion

editMost African Americans in Baltimore are Christians, generally either Protestant or Catholic. Smaller numbers of African-American Christians belong to denominations such as Mormonism, the Jehovah's Witnesses, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Oriental Orthodoxy. Minorities of African Americans belong to other religions such as Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, and the Black Hebrew Israelites, while some are atheist or agnostic. A growing number of black millennials, particularly young black women, are leaving the black church to embrace witchcraft rooted in traditional African religions.[54]

Christianity

editProtestantism

editThe Orchard Street United Methodist Church is the oldest standing structure built by African Americans in the city of Baltimore. The church was founded in 1825 by Truman Le Pratt, a West Indian former slave of Governor John Eager Howard. The building now houses offices for the National Urban League.[55]

Catholicism

editBaltimore has a prominent and well-established African-American Roman Catholic community. St. Francis Xavier Church in the neighborhood of Oliver, claims to be the "first Catholic church in the United States for the use of an all-colored congregation", established in 1863. The church attracted the black elite of Baltimore. The founders of the church were Black Haitian refugees from Saint-Domingue, along with the Sulpician Fathers.[56][57] The second black parish to be established in Baltimore was St. Monica's in 1883, in the area where Camden Yards now stands.[56] By the early 20th century, Baltimore was home to two other Black Catholic parishes: St. Peter Claver and St. Barnabas.[57]

Judaism

editBaltimore is home to a small population of African-American Jews. Historically, there were strong links between African-American and Jewish-American communities in Baltimore and many white Jewish Baltimoreans were strong supporters of the civil rights movement. However, there has been tension between the two communities, with instances of anti-black racism from white Jews such as the 2010 Park Heights beating of a black teenager by white members of an Orthodox Jewish community patrol group.[58] In majority white Jewish spaces in Baltimore, white Jews are sometimes accepted while black Jews and other Jews of color may face skepticism and questioning of their identity. Congregation Beth HaShem on Collington Avenue was established as a synagogue for African-American Jews. Rabbi George McDaniel, founder of Beth HaShem, claims that white Ashkenazi Jews of Russian and Eastern European descent are not questioned about their Jewishness because they are white whereas "If you're black and you say I'm Jewish, now you have to prove your Jewishness...Sometimes people walk up to us and ask: are you Jewish?...You're questioned to the point of -- prove you're Jewish."[59] Black Jews in Baltimore experience both racism for being black and antisemitism for being Jewish, with some Black Jewish Baltimoreans reporting being called the slur "schvartze" by non-black Jews as well as being harassed by gentiles for wearing a kippah.[60]

Irreligion

editSeveral hundred African Americans in Baltimore belong to black atheist groups.[61]

Majority African-American neighborhoods in Baltimore

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

- Ashburton[62]

- Barclay[63]

- Belair-Edison[64]

- Berea

- Better Waverly

- Broadway East

- Brooklyn

- Cedonia

- Cherry Hill

- Coldstream-Homestead-Montebello

- Coppin Heights

- East Baltimore Midway

- Edmondson Village

- Ednor Gardens-Lakeside

- Ellwood Park

- Glen, Baltimore

- Govans, Baltimore[65]

- Greenmount West

- Gwynn's Falls

- Hillen, Baltimore

- Lakeland

- Langston Hughes

- Liberty Square

- Loch Raven

- Johnston Square

- Jonestown

- McElderry Park[66]

- Middle East[67]

- Mid-Govans[65]

- Mondawmin

- Mosher

- Northwood[65]

- Oliver[68]

- Pen Lucy

- Pimlico

- Ramblewood

- Rosemont

- Sandtown-Winchester[65]

- Stonewood-Pentwood-Winston

- Upton

- Washington Hill

- Waverly

- Westgate

- West Hills

- Westport

- Wilson Park

- Woodbourne Heights

Notable African Americans from Baltimore

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2019) |

Gallery

edit- Victorine Q. Adams, the first African-American woman to serve on the Baltimore City Council.

- Benjamin Banneker, self-taught mathematician and astronomer who predicted a solar eclipse with precision[69]

- Muggsy Bogues, shortest player in the history of the National Basketball Association (NBA)

- Clarence H. Burns, a Democratic politician and first African American mayor of Baltimore in 1987.

- Cab Calloway, a jazz singer, dancer, and bandleader.

- Kevin Clash, a puppeteer, director and producer whose characters included Elmo, Clifford, Benny Rabbit, and Hoots the Owl.

- Ta-Nehisi Coates, author and journalist who writes on socio-political issues related to African Americans and white supremacy.

- Marshall "Eddie" Conway, a leading member of the Baltimore chapter of the Black Panther Party who in 1971 was convicted of murder of a police officer a year earlier, in a trial with many irregularities.

- Elijah Cummings, civil rights advocate and politician who served in the Maryland House of Delegates for fourteen years and in the United States House of Representatives for Maryland’s 7th congressional district.[69]

- Carl Dix, a founding member and representative of the Revolutionary Communist Party, USA (RCP).

- Sheila Dixon, served as the forty-eighth mayor of Baltimore.

- Bea Gaddy, a Baltimore City Council member and a leading advocate for the poor and homeless known locally as the "Mother Teresa of Baltimore."

- Joe Gans, a professional boxer known as the "Old Master", the first African-American world boxing champion of the 20th century.

- L. S. Alexander Gumby, an archivist and historian whose collection of 300 scrapbooks documenting African-American history have been part of the collection of Columbia University.

- Ken Harris, a Democratic politician who served on the Baltimore City Council.

- William Ashbie Hawkins, one of Baltimore's first African American lawyers.

- Billie Holiday, a jazz singer with a career spanning nearly thirty years who had a seminal influence on jazz music and pop singing.

- Reginald Lewis, a businessman who was one of the richest African-American men in the 1980s, worth $400 million, and the first African American to build a billion-dollar company

- Lillie Mae Carroll Jackson, pioneer civil rights activist who was an organizer of the Baltimore branch of the NAACP.

- Thurgood Marshall, first African American U.S. Supreme Court Justice and lead counsel for the landmark school desegregation case, Brown v. Board of Education (1954).[70]

- Angel McCoughtry, a professional basketball player for the Atlanta Dream of the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA).

- DeRay Mckesson, a Black Lives Matter activist, podcaster, and former school administrator.

- Enolia McMillan, an African American educator, civil rights activist, and community leader and the first female national president of the NAACP.

- Sharon Green Middleton, a Democratic politician serving as the acting President of the Baltimore City Council during Jack Young's service as Acting Mayor of Baltimore.

- Abbie Mitchell, a soprano opera singer known for singing the role of "Clara" in the premier production of George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess.

- Clarence Mitchell Jr., a civil rights activist who was the chief lobbyist for the NAACP for nearly 30 years.

- Clarence Mitchell III, a politician who served in the Maryland Senate and the Maryland House of Delegates.

- Keiffer Mitchell Jr., a politician who once served in the Maryland House of Delegates and the Baltimore City Council.

- Parren Mitchell, the first African American elected to Congress from Maryland.

- Wes Moore, a politician who has served as the first African-American governor of Maryland since 2023.

- Nick J. Mosby, a politician who is currently the chair of the Baltimore City Council and a former member of the Maryland House of Delegates from the 40th District.

- John H. Murphy Sr., an African-American newspaper publisher, born into slavery, best known as the founder of the Baltimore Afro-American.

- Pauli Murray, a civil rights activist who became a lawyer, a women's rights activist, an author, and the first African-American woman to be ordained as an Episcopal priest.

- Felicia "Snoop" Pearson, an actress and author who played "Snoop" on The Wire and wrote an autobiographical memoir titled Grace After Midnight.

- Catherine Pugh, a Democratic politician, who served as the 51st mayor of Baltimore from 2016 to 2019.

- Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, a politician and attorney who served as the 49th Mayor of Baltimore from 2010 to 2016.

- Oscar Requer, a former detective of the Baltimore Police Department.

- Gloria Richardson, the leader of the Cambridge Movement, a civil rights struggle in the early 1960s in Cambridge, Maryland.

- April Ryan, a journalist and author who has served as a White House correspondent since 1997.

- Kurt Schmoke, a politician and lawyer who served as the 46th mayor of Baltimore, the first African American to be elected mayor.

- Brandon Scott, the current mayor of the Baltimore since 2020.

- Serpentwithfeet, a Baltimore-born experimental musician based in Brooklyn, New York.

- Tupac Shakur, a rapper, writer, and actor considered by many to be one of the greatest rappers of all time.

- André De Shields, an actor, singer, director, dancer, novelist, choreographer, lyricist, composer, and professor.

- Breanna Sinclairé, a transgender singer who became the first transgender woman to sing the American national anthem at a professional sporting event.

- Jada Pinkett Smith an actress, singer-songwriter, and businesswoman. Will Smith is her husband.

- Rain Pryor, an actress and comedian who is the daughter of the late comedian Richard Pryor.

- Sonja Sohn, an actress and director best known for her roles as Detective Kima Greggs on the HBO drama The Wire.

- Carl Stokes, a politician who represents the 12th district on the Baltimore City Council.

- Melvin L. Stukes, a politician who represented the 44th legislative district in the Maryland House of Delegates.

- Mary L. Washington, a Democratic politician who was elected in 2018 to the Maryland Senate to represent the state's 43rd district.

- William A. White, an American-born Nova Scotian who was commissioned as the first black officer in the British army.

- Deniece Williams, a Grammy-winning singer, songwriter and producer who has been described as "one of the great soul voices" by the BBC.

- Montel Williams, actor and television show host

- William Llewellyn Wilson, a conductor, musician, music critic, and music educator who was the first conductor of the first African American symphony in the city of Baltimore.

- Jack Young, a Democratic politician and the 52nd mayor of Baltimore from 2019 to 2020.

Fictional African Americans from Baltimore

editSee also

edit- African Americans in Maryland

- Desegregation of the Baltimore City Public Schools

- Ethnic groups in Baltimore

- History of Baltimore

- Atlantic Creole

- Female slavery in the United States

- History of slavery in Maryland

- Maryland-in-Africa

- Slavery in the colonial history of the United States

- Tobacco colonies

- History of Africans in Baltimore

- History of Ethiopian Americans in Baltimore

- History of Caribbean Americans in Baltimore

- History of Hispanics and Latinos in Baltimore

- History of Native Americans in Baltimore

- History of White Americans in Baltimore

- History of the Appalachian people in Baltimore

- History of Koreans in Baltimore

- History of Syrians in Baltimore

- History of Russians in Baltimore

- History of the Irish in Baltimore

- History of Italians in Baltimore

- History of Greeks in Baltimore

- History of Poles in Baltimore

- History of Czechs in Baltimore

- History of the French in Baltimore

- History of Lithuanians in Baltimore

- History of Ukrainians in Baltimore

- History of the Jews in Baltimore

- History of the Germans in Baltimore

References

edit- ^ "Baltimore - Place Explorer - Data Commons". datacommons.org.

- ^ Alabaster cities: urban U.S. since 1950. John R. Short (2006). Syracuse University Press. p.142. ISBN 0-8156-3105-7

- ^ "Two Baltimores: The White L vs. the Black Butterfly". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ a b c "Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "Black Appalachian Families". Western Michigan University. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "Census Tracts Baltimore, Md" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ a b "Census 1980, 1990 and 2000 Profile of General Demographic Characteristics (PDF Format)" (PDF). Maryland Department of Planning, Maryland State Data Center. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). 2000 United States Census. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Race and Hispanic or Latino Origin: 2010". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "2013-2017 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Baltimore's Demographic Divide". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "Baltimore Black Population". blackdemographics.com.

- ^ "Latinos, Blacks Show Strong Growth in San Antonio as White Population Declines". August 13, 2021.

- ^ "BLACKS BEFORE THE LAW IN COLONIAL MARYLAND". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved 2020-08-28.

- ^ "Baltimore: A City of Firsts". Visit Baltimore. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Christopher Phillips Freedom's Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1791-1860 (1997)

- ^ Rice, Laura. Maryland History In Prints 1743-1900. p. 77.

- ^ T. Stephen Whitman, "Industrial Slavery at the Margin: the Maryland Chemical Works," Journal of Southern History 1993 59(1): 31-62,

- ^ Stephen Whitman, "Manumission and the Transformation of Urban Slavery," Social Science History 1995 19(3): 333-370

- ^ a b Collier-Thomas, Bettye (1974). The Baltimore Black Community, 1865-1910. Washington, DC: George Washington University. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Richard Paul Fuke, "Blacks, Whites, and Guns: Interracial Violence in Post-emancipation Maryland," Maryland Historical Magazine 1997 92(3): 326-347

- ^ Robert S. Wolff, "The Problem of Race in the Age of Freedom: Emancipation and the Transformation of Republican Schooling in Baltimore, 1860-1867," Civil War History 2006 52(3): 229-254

- ^ "Landmark Legislation: Civil Rights Act of 1875". United States Senate. Senate Historical Office. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ "Plessy v. Ferguson (1896)". National Archives. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ "Session Laws, 1904, Laws of Maryland, ch. 109". Archives of Maryland Online. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ "Session Laws, 1908, Laws of Maryland, ch. 617". Archives of Maryland Online. Archives of Maryland Online. Retrieved 2023-12-18.

- ^ Power, Garrett (May 1, 1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: The Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913". Faculty Scholarship. 184. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Power, Garrett (1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: the Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910–1913". Maryland Law Review. 42 (2): 299–300.

- ^ Power (1983), p. 289.

- ^ Power, Garrett (May 1, 1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: The Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913". Faculty Scholarship. 184. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Bock, James. "'Apartheid, Baltimore Style' City Housing Suit and History of Bias". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ "1966–1976: After the Unrest". Baltimore Heritage. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ Sheryl Gay Stolberg, "Crowds Scatter as Baltimore Curfew Takes Hold," New York Times, April 28, 2015

- ^ "The Relevatory Power of Language". Maryland Humanities Council. May 11, 2019.

- ^ a b DeShields, Inte'a. "Baldamor, Curry, and Dug': Language Variation, Culture, and Identity among African American Baltimoreans". Podcast. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Sean Bugg, "Dan Furmansky and Equality Maryland's growing fight for the state's gay and lesbian community", Metro Weekly, May 18, 2006.

- ^ Jonathan Bor, "Gay Blacks at Highest Aids Risk: Researchers Seek To Explain Racial Disparity Among Gay, Bisexual Men", The Baltimore Sun, December 4, 2007.

- ^ "Meet the Newest NHVREI Local Partners", The NIAID HIV Vaccine Research Education Initiative, 2009.

- ^ "Empowering New Concepts Inc", POZ Magazine, 2010.

- ^ "Straight talk about the Down Low". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Black, gay and Christian, Marylanders struggle with conflicts". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "'Where do we go?' Baltimore's gay nightlife takes a hit with Grand Central's Impending Closure". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ "The Forgotten World of Communist Bookstores". Jacobin Magazine. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ Gross, Terry (February 18, 2009). "Ta-Nehisi Coates' 'Unlikely Road to Manhood'". Fresh Air. NPR. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "Black History Month & Baltimore's Black History". Baltimore.org. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Pride, Felicia (June 4, 2008). "Manning Up: The Coates Family's Beautiful Struggle in Word and Deed". Baltimore City Paper. Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "Baltimore City Newspapers". Johns Hopkins University Library. Archived from the original on 2008-02-15. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ Farrar, Hayward (1998-05-30). The Baltimore Afro-American: 1892-1950. Greenwood Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-313-30517-X.

- ^ Taylor, Asha (July 18, 2005). "Baltimore Celebrates Opening of Maryland Black History Museum Named For Late Business Tycoon Reginald F. Lewis". Jet. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Wood, Marcus (2009). "Slavery, Memory, and Museum Display in Baltimore: The Great Blacks in Wax and the Reginald F. Lewis". Curator: The Museum Journal. 52 (2): 147–167. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2009.tb00341.x.

- ^ a b "Royal Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "12 O'Clock Boys' Eric Blair takes Baltimore audience behind the scenes". Baltimore Post-Examiner. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ N'Duka, Amanda (September 19, 2018). "Sony & Overbrook Entertainment Team On Film About Dirt-Bike Riders". Deadline. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ "The Witches of Baltimore". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ George J. Andreve (1975). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Orchard Street United Methodist Church" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ a b "Telling the tale Black Catholics in Baltimore". Archdiocese of Baltimore. 19 January 2012. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ a b Gatewood, Willard B. (1990). Aristocrats of Color: The Black Elite, 1880-1920. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 306. ISBN 1-55728-593-4. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "The story behind Baltimore's Jews and their African-American ties". Times of Israel. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "In face of doubters, Black rabbi finds his spiritual destiny Faith is Proof Enough". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Black Jews Are Being Chased Out Of the Jewish Community By Racism. Here Are Their Stories". The Forward. Retrieved 2019-05-19.

- ^ "Black atheists say their concerns have been overlooked for too long". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "In past and present, Ashburton is special". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ^ "Barclay-Midway-Old Goucher Small Area Plan" (PDF). Baltimore Department of Planning. June 2005. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ "Belair-Edison: Fighting for a neighborhood for 'the middle'". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ a b c d "Legacy of segregation lingers in Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

- ^ "America's 'Inner City' Problem, As Seen In One Baltimore Neighborhood". Forbes. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Gentrify or die? Inside a university's controversial plan for Baltimore". The Guardian. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 2019-05-09.

- ^ "Blighted East Baltimore neighborhood finally turning around, residents say". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2019-05-12.

- ^ a b "33 Black Heroes From Maryland You Need To Know | ACLU of Maryland | ACLU of Maryland exists to empower Marylanders to exercise their rights so that the law values and uplifts their humanity". www.aclu-md.org. 2023-02-01. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

- ^ "A Lasting Legacy: Notable Baltimoreans". Explore Baltimore. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

Further reading

edit- Allen, Devin. A Beautiful Ghetto, Haymarket Books, 2017.

- Baum, Howell S. Brown in Baltimore: School Desegregation and the Limits of Liberalism, (Cornell University Press, 2010).

- Diemer, Andrew Keith. Black nativism: African American politics, nationalism and citizenship in Baltimore and Philadelphia, 1817 to 1863 (Temple University, 2011) online.

- Durr, Kenneth D. Behind the backlash: White working-class politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980 (Univ of North Carolina Press, 2003).

- Farrar, Hayward. The Baltimore Afro-American, 1892-1950 (Greenwood, 1998), newspaper history. online

- Fernández-Kelly, Patricia. The Hero's Fight: African Americans in West Baltimore and the Shadow of the State, (Princeton University Press, 2016).

- Gomez, Marisela B. Race, Class, Power, and Organizing in East Baltimore: Rebuilding Abandoned Communities in America, (Lexington Books, 2015).

- Mcdougall, Harold. Black Baltimore: A New Theory of Community, (Temple University Press, 1993).

- Malka, Adam. The Men of Mobtown: Policing Baltimore in the Age of Slavery and Emancipation (UNC Press Books, 2018).

- Müller, Viola Franziska. "Runaway Slaves in Antebellum Baltimore: An Urban Form of Marronage?." International Review of Social History 65.S28 (2020): 169-195. online

- Nix, Elizabeth. Baltimore '68: Riots and Rebirth in an American City, (Temple University Press, 2011).

- Orser, W. Edward. Blockbusting in Baltimore: The Edmondson Village Story (University Press of Kentucky, 2014). online

- Phillips, Christopher. Freedom's Port: the African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860, (Urbana : University of Illinois Press, 1997).

- Pietila, Antero. Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Ivan R. Dee, 2010).

- Pryor-Trusty, Rosa; Taliaferro, Tonya. African-American Entertainment in Baltimore (Black America Series), (Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

- Williams, Jennie K. "Trouble the water: The Baltimore to New Orleans coastwise slave trade, 1820–1860." Slavery & Abolition 41.2 (2020): 275-303.

- Wolff, Robert S. "The problem of race in the age of freedom: emancipation and the transformation of republican schooling in Baltimore, 1860-1867." Civil War History 52.3 (2006): 229-254.

External links

edit- A Lasting Legacy: Baltimore’s African American History, Explore Baltimore

- African American Marylanders

- African Americans in Baltimore

- Black Panther Party Baltimore, Maryland Branch 1968-1972, Black Panther Party Alumni official website]

- Experience African-American Culture in Baltimore

- New Black Panther Party official page, Facebook

- Percentage of Blacks (African Americans) in Baltimore, MD by Zip Code