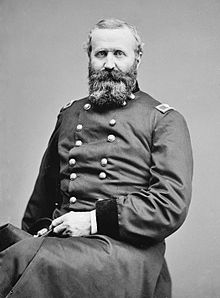

Alexander Hays (July 8, 1819 – May 5, 1864) was a Union Army general in the American Civil War who was killed at the Battle of the Wilderness in 1864.

Alexander Hays | |

|---|---|

Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays | |

| Nickname(s) | "Fighting Elleck" |

| Born | July 8, 1819 Franklin, Pennsylvania |

| Died | May 5, 1864 (aged 44) Battle of the Wilderness, Virginia |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1844–1848, 1861–1864 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | Regular Army |

| Commands | 63rd Pennsylvania Infantry |

| Battles / wars | Mexican–American War American Civil War |

Early life and career

editHays was born in Franklin, Pennsylvania, the son of Samuel Hays, a member of Congress and general in the Pennsylvania militia. He studied at Allegheny College and then transferred to the United States Military Academy in his senior year, graduating in 1844, ranking 20th out of 25 cadets. Among his classmates were future Civil War generals Alfred Pleasonton and Winfield S. Hancock. He became a close personal friend of Ulysses S. Grant, who had graduated the year before. Hays was brevetted as a second lieutenant in the 8th U.S. Infantry. He served in the Mexican–American War, and won special distinction in an engagement near Atlixco. In April 1848, he resigned his commission in the army and returned to Pennsylvania.

He settled in Venango County, where he engaged in the manufacture of iron from 1848 to 1850 before briefly leaving for the California gold fields to seek his fortune. Failing that, he returned home and became an assistant construction engineer for the railroad until 1854. From 1854 through 1860, Hays was a civil engineer for the city of Pittsburgh, helping plan several bridge building projects.

Civil War

editAt the beginning of the Civil War, Hays re-entered the service as colonel of the 63rd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment, also holding the rank of captain in the 16th U.S. Infantry in the regular army to date from May 14, 1861. His men knew him to be "as brave as a lion."[1] During the Peninsula Campaign, he was attached with his regiment to the first brigade of Kearny's division of Heintzelman's III Corps. He fought in the battles of Yorktown, Williamsburg, Seven Pines, Savage's Station, and Malvern Hill. At the close of the Seven Days Battles, he was appointed a brevet lieutenant colonel in the regular army for gallantry in action, as Hays had directed a bayonet charge with his regiment into the enemy lines to cover the retreat of his brigade. Hays briefly went on sick leave a month later, suffering from partial blindness and paralysis of his left arm, injuries incurred from battle.[2]

Hays resumed command of the 63rd Pennsylvania during the Northern Virginia Campaign in August and again led a charge in the Second Battle of Bull Run, receiving a painful wound that shattered his leg. While recovering, he was appointed brigadier general of volunteers, September 29, 1862. Early in 1863 Hays was made a brigade commander in XXII Corps in the defenses of Washington, D.C. His brigade, composed largely of troops surrendered after the Battle of Harpers Ferry, was added to the Army of the Potomac as the 3rd Brigade, 3rd Division, II Corps.

Due to his seniority, after the reassignment of William H. French, Hays was assigned command of the third Division during the Gettysburg Campaign. (Col. George L. Willard took command of Hays's brigade.) During the Battle of Gettysburg, Hays's division defended the right of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge. The division held firm in the repulse of the Confederate attack on July 3, 1863, even counterattacking the left flank of the Confederate attacking force. Hays's passion and flair for the dramatic led to a notable incident as Confederate prisoners were being rounded up: "When the smoke cleared, Hays, who was unhurt but had had two horses shot out from under him, kissed his aide in the exhilaration of the moment, grabbed a captured Rebel battle flag and riding down the division's line dragged it in the dirt ..."[3] For his efforts at Gettysburg, Hays gained the brevet rank of colonel in the regular army. Later returning to divisional command before the Bristoe Campaign, he was engaged at Auburn and Mine Run.

Hays's last major engagement as a division commander was at Morton's Ford on the Rapidan River in Virginia on February 6, 1864. A demonstration in force by II Corps became a bloody fiasco with Hays's division suffering 252 casualties. Stories about Hays being drunk on duty arose from that defeat by Confederates of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell's corps.[4] However, Hays was keenly aware of and sensitive to rumors of his drinking and specifically addressed them in letters to his family. And given that his wife, Annie, was present in camp during the Battle of Morton's Ford, it is highly likely that General Hays was sober during the battle.

When the Army of the Potomac was reorganized in early 1864 under his friend Grant's guidance, Hays was placed in command of the 2nd Brigade of Birney's 3rd Division of the II Corps. Hays was unhappy at losing division command but was happy to serve once more under Birney, with whom he had campaigned in III Corps.[5] During the Overland Campaign, Hays was killed in action near the junction of the Brock and Plank Roads in the Wilderness, being struck in the head by a Minié ball.

He was buried in Allegheny Cemetery (Section 8, Lot 149) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. At a campaign stop in Pittsburgh during his run for the presidency, Ulysses S. Grant visited Hays's grave and wept openly.[6]

Honors

editPost #3 of the Grand Army of the Republic in Pittsburgh was named for General Alexander Hays, as was Fort Hays and the city of Hays in Kansas. Alexander Hays Road in Bristow, Virginia, is named for him. The road is in New Bristow Village in Bristow, Virginia, adjacent to the Bristoe Station Battlefield.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Tagg, p. 53.

- ^ "Allegheny Cemetery webpage for Hays". Archived from the original on 2007-01-04. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Tagg". Archived from the original on 2006-11-04. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ Mahood, pp. 142–48.

- ^ Mahood, pp. 150–52.

- ^ "Allegheny Cemetery website". Archived from the original on 2007-01-04. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link), citing period Pittsburgh newspapers.

References

edit- Tagg, Larry. The Generals of Gettysburg. Campbell, CA: Savas Publishing, 1998. ISBN 1-882810-30-9.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- General Alexander Hays, USA, History Central.

- "Allegheny Cemetery webpage for Alexander Hays". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2006.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Further reading

edit- Fleming, George T. General Alexander Hays at the Battle of Gettysburg. Pittsburgh: 1913. OCLC 6598281.

- Fleming. George T., ed. Life and Letters of Alexander Hays. Pittsburgh: 1919. OCLC 2435162.

- Mahood, Wayne. Alexander "Fighting Elleck" Hays: The Life of a Civil War General, from West Point to the Wilderness. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2005. ISBN 0-7864-2213-0.

External links

edit- Photos of Hays's Grave and monument

- "Alexander Hays". Find a Grave. Retrieved 2008-07-01.