A major contributor to this article appears to have a close connection with its subject. (January 2024) |

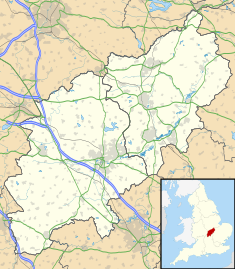

Apethorpe Palace (pronounced Ap-thorp), formerly known as "Apethorpe Hall", is a Grade I listed[1] country house, dating to the 15th century, close to Apethorpe, Northamptonshire. It was a "favourite royal residence" for James I.[2]

| Apethorpe Palace | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formerly Apethorpe Hall | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Apethorpe Palace south elevation

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The house is acknowledged as one of the finest remaining examples of a Jacobean stately home[3] and one of Britain's ten best palaces.[4] It holds a particular importance due to its ownership by, and role in entertaining, Tudor and Stuart monarchs; Elizabeth I inherited the estate from her father Henry VIII and her successor, James I, personally contributed to its 1622 extension, housing the state rooms and featuring some of the most important surviving plasterwork and fireplaces of the period.[5] There were at least thirteen extended royal visits – more than to any other house in the county – between 1566 and 1636,[6] and it was at Apethorpe, in August 1614, that King James met his favourite and speculated lover, George Villiers, later to become Duke of Buckingham.[7][6] A series of court masques written by Ben Jonson for James I were performed while the King was in residence at Apethorpe.[8][9] The house was also lived in regularly by Charles I.[2]

History

editIn May 1231 Henry III granted the manor of Apethorpe to Ralph le Breton; however on 21 June 1232 the manor was taken back into the king's hands.[10][11] In the 15th century the manor was owned by Sir Guy Wolston. In 1515 Apethorpe was purchased by Henry Keble, grandfather of Lord Mountjoy, who sold the manor to Henry VIII.[12]

Apethorpe was left to Princess Elizabeth in her father Henry VIII's will. In April 1551 Sir Walter Mildmay acquired it from Edward VI in exchange for property in Gloucestershire and Berkshire. Queen Elizabeth dined with Mildmay at Apethorpe on her progress in 1562, 1566 and 1587. He added a stone chimney-piece engraved with his motto dated 1562,[13][14] and after his death the house was inherited by his eldest son Sir Anthony Mildmay (c. 1549–1617), from whom Apethorpe passed to his daughter Mary (1581/2–1640) and her husband, Sir Francis Fane (1617),[15] later Earl of Westmorland. Apethorpe remained in the Fane family for nearly three centuries.

The 12th Earl and his son came into financial difficulties and so they sold the house in 1904 to Henry Brassey. After World War II the Brassey family moved into the manor house and much of the adjoining estate was sold. The house became an approved school under the Catholic Church, but in 1982 the school closed and in 1983 the house was sold to Wanis Mohamed Burweila, who wanted to found a university in the cloisters and courtyards of Apethorpe. His plans never materialised and he left the country for political reasons, leaving the house empty. When English Heritage started its Buildings at Risk Register in 1998 the house was included on it as one of the most important houses at risk.[16]

In September 2004 the entire remaining estate was compulsorily purchased by the British Government under section 47 of the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. This was only the second time the government had resorted to using these powers. English Heritage spent £8 million refurbishing it to make it waterproof. Much of the work was carried out by Stamford restoration and conservation builders, E. Bowman & Sons Ltd. From 2007, buyers were sought, in spite of an estimated £6 million still required in renovation (as of 2014, the house was without any plumbing, power or heating). In 2008, the asking price had been reduced, but remained upwards of £4.5 million.[17]

In December 2014, English Heritage announced that Baron von Pfetten, a French anglophile and keen field sportsman, had bought the property. Simon Thurley, English Heritage's chief executive, welcomed the purchase:[18]

"Since 2000 English Heritage has consistently said that the best solution for Apethorpe is for it to be taken on by a single owner, who wants to continue to restore the house and to live in it; especially one who has experience of restoring historic buildings and is prepared to share its joys with a wide public, as Baron Pfetten will do. Apethorpe is certainly on a par with Hatfield and Knole and is by far the most important country house to have been threatened with major loss through decay since the 1950s."

Baron Pfetten agreed to publicly open the house 50 days a year for 80 years. This is much longer than the normal 10 year period for English Heritage grant-aided properties.[18]

Before the sale English Heritage and Baron Pfetten agreed to rename the house "Apethorpe Palace" due to its royal ownership and use, along with its outstanding historic and architectural significance.[19] In a video introducing the sale, English Heritage director Simon Thurley described the house as "the Royal Palace of Apethorpe."[18] Since April 2015, the house has been officially registered as Apethorpe Palace in the National Heritage List.[20] The decision was met with some concern.[21] Since 2015 the palace has been undergoing renovation works.[22][23]

Architecture and gardens

editThe house has been significantly altered and extended throughout its history. The first major alteration, the Jacobean royal extension, is attributed to Thomas Thorpe, brother of John Thorpe (at times himself attributed). The second, Neo-Palladian modifications which were planned to be more widespread, are attributed to Roger Morris. The third & final, largely Neo-Jacobean embellishments and internal reworking, was by Sir Reginald Blomfield.[24][25] As a result of these, it is vast, with a floor area of approximately 51,000 square feet (4,700 m2).[26] This size, along with its three courtyards,[27] led to Country Life saying it has "something of the character of a Cambridge college".[25] For similar reasons, a later article stated that the entire palace "splits quite naturally into three contiguous houses: the Jacobean Hall, a central medieval hall house, and an Elizabethan hall house incorporating the 18th-century orangery."[28]

Apethorpe was large enough to accommodate both King James and his consort Anne of Denmark in August 1605.[29] In 1622 King James financed an enlargement of the house and rebuilding of the south range with a new suite of state rooms on the first floor, and an open gallery around the perimeter of the house on the second floor. This suite of state rooms consisted of the Dining Chamber, the Drawing Chamber, the King Bedchamber, the Prince of Wales Bedchamber (with the three feathers carved on the fireplace) and the Long Gallery (last complete set of original Jacobean State apartments left in England). The entrance is still now surmounted by a statue of James I dating from that period. The King Bedchamber was embellished with a hunting scene over the fireplace and the royal arms decorated the ceiling. These State rooms contain a notable series of fireplaces incorporating in the carving iconographical statements such as the nature of kingship.[30] During renovations in the 21st century, workers discovered a passageway linking James' apartment to that of his favourite, George Villiers.[17][31] The discovery of the secret passage, according to Emma Dabiri, provides an "intriguing clue to the nature of the affair" between the King and Duke, who wrote each other love letters and were inseperable, she says.[32] Historian Keith Coleman see the passage, dated to 1622-24, as evidence that physical intimacy between the pair may have lasted into the last years of James's life.[33]

Its Lebanese cedar, planted in 1614 and considered to be the oldest surviving one in England, is a scheduled monument. Blomfield also worked on the formal gardens.

Film location

editThe house has been used for filming scenes in Another Country and Porterhouse Blue. The restoration and attempts to sell the property were the subject of a fly on the wall documentary first shown on BBC Two in April 2009.[34]

References

edit- ^ Historic England. "Apethorpe Palace Formerly Known As Apethorpe Hall (1040083)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Apethorpe Palace". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Gaches, Philip (2008). "Apethorpe Hall's Jacobean Ceilings". www.buildingconservation.com. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ "Britain's 10 best palaces".

- ^ "Historic England – Championing England's heritage | Historic England". English-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b "Historic England – Championing England's heritage | Historic England". English-heritage.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 December 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Kathryn A. Morrison, Apethorpe (Yale, 2016), 92.

- ^ "The progresses, processions, and magnificent festivities, of King James the First, his royal consort, family, and court : collected from original MSS., scarce pamphlets, corporation records, parochials registers, &c., &c : Nichols, John, 1745–1826 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive". Archive.org. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ E. K. Chambers, The Elizabethan Stage (1923) vol. IV, 83

- ^ Vincent 1996, pp. 269, 298, 312.

- ^ "Fine Rolls Henry III: 16 HENRY III (28 October 1231 – 27 October 1232)". Finerollshenry3.org.uk. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ The Victoria History of the County of Northampton, Volume 2. Constable. 1906. p. 543. ISBN 9780712904506.

- ^ Ford 2004.

- ^ "Apethorpe". British History Online. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1984. Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Barron 1905, p. 9.

- ^ Heritage at Risk Register: Apethorpe

- ^ a b Graham 2008.

- ^ a b c "Future Secured for Magnificent Grade I Listed Jacobean Palace of Apethorpe | English Heritage". Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ In a sale and conveyance by English Heritage: "Due to its past royal ownership and use, along with its outstanding historic and architectural significance, English Heritage and the new owner jointly agreed, prior to the sale in 2014, that the building would henceforth be known as Apethorpe Palace" [1]

- ^ Historic England. "Apethorpe Palace formerly known as Apthorpe Hall (1040083)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Gallagher, Paul (5 April 2015). "It's a palace, not a hall: French baron's stately home is renamed". The Independent. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Red Baron's Jacobean Apethorpe Palace marks its rebirth with party". TheGuardian.com. 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Baron von Pfetten's Puppy Show - Apethorpe Palace".

- ^ Morrison, Kathryn (2016). Apethorpe: The Story of an English Country House. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300148701.

- ^ a b "The rebirth of Apethorpe Hall". Country Life. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ "Apethorpe Hall sold to French baron after £8m English Heritage restoration". BBC News. 7 January 2015. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ "Historic England – Championing England's heritage | Historic England". English-heritage.org.uk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Apethorpe Hall". Country Life. 9 June 2008.

- ^ Kathryn A. Morrison, Apethorpe (Yale, 2016), 91.

- ^ "Apethorpe | British History Online". British-history.ac.uk. 20 March 1909. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Kennedy, Maev (3 August 2007). "Restoration opens doors on a royal scandal after 400 years". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Glasgow". Britain's Lost Masterpieces. Series 2. 27 September 2017. BBC. BBC 4.

- ^ Coleman, Keith (30 June 2023). "Chapter 11: Steenie". James I: The King Who United Scotland and England. Pen and Sword History. ISBN 978-1-3990-9360-6. Retrieved 5 January 2024.

- ^ Appleyard 2009.

References

edit- Alexander, Jennifer S.; Morrison, Kathryn A. (2007). "Apethorpe Hall and the workshop of Thomas Thorpe, mason of King's Cliffe: a study in masons' marks". Architectural History. 50: 59–94. doi:10.1017/S0066622X00002884. S2CID 194946520.

- Appleyard, Bryan (27 April 2009). "English Heritage becomes reality TV show". The Times.[dead link]

- Barron, Oswald (January 1905). "The Fanes". The Ancestor (XIII). London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- Historic England. "Grade I (1040083)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- English Heritage. "Visitor information – Apethorpe Hall". English Heritage.

- Ford, L.L. (2004). "Mildmay, Sir Walter (1520/21–1589)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18696. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Graham, Fiona (5 June 2008). "To the manor bought". BBC News.

- Pevsner, Sir Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2002) [1973]. Northamptonshire (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of England). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09632-1.

- Smith, Pete (2007). "The Palladian Palace at Apethorpe". English Heritage Historical Review. 2: 84–105. doi:10.1179/175201607797644095.

- Vincent, Nicholas (1996). Peter des Roches: An Alien in English Politics, 1205–1238. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521522151. Retrieved 27 November 2013.