Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take varied forms, including artistic pottery, including tableware, tiles, figurines and other sculpture. As one of the plastic arts, ceramic art is a visual art. While some ceramics are considered fine art, such as pottery or sculpture, most are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramic art can be created by one person or by a group, in a pottery or a ceramic factory with a group designing and manufacturing the artware.[1]

In Britain and the United States, modern ceramics as an art took its inspiration in the early twentieth century from the Arts and Crafts movement, leading to the revival of pottery considered as a specifically modern craft. Such crafts emphasized traditional non-industrial production techniques, faithfulness to the material, the skills of the individual maker, attention to utility, and an absence of excessive decoration that was typical to the Victorian era.[2]

The word "ceramics" comes from the Greek keramikos (κεραμεικός), meaning "pottery", which in turn comes from keramos (κέραμος) meaning "potter's clay".[3] Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae.

There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures, like that of the Nok in Africa over 2,000 years ago. Cultures especially noted for ceramics include the Chinese, Cretan, Greek, Persian, Mayan, Japanese, and Korean cultures, as well as the modern Western cultures.

Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics.

Materials

editDifferent types of clay, when used with different minerals and firing conditions, are used to produce different types of ceramic, including earthenware, stoneware, porcelain and bone china.

Earthenware

editEarthenware is pottery that has not been fired to vitrification and is thus permeable to water.[4] Many types of pottery have been made from it from the earliest times, and until the 18th century it was the most common type of pottery outside the far East. Earthenware is often made from clay, quartz and feldspar. Terracotta, a type of earthenware, is a clay-based unglazed or glazed ceramic,[5] where the fired body is porous.[6][7][8][9] Its uses include vessels (notably flower pots), water and waste water pipes, bricks, and surface embellishment in building construction. Terracotta has been a common medium for ceramic art (see below).

Stoneware

editStoneware is a vitreous or semi-vitreous ceramic made primarily from stoneware clay or non-refractory fire clay.[10] Stoneware is fired at high temperatures.[11] Vitrified or not, it is nonporous;[12] it may or may not be glazed.[13]

One widely recognised definition is from the Combined Nomenclature of the European Communities, a European industry standard states "Stoneware, which, though dense, impermeable and hard enough to resist scratching by a steel point, differs from porcelain because it is more opaque, and normally only partially vitrified. It may be vitreous or semi-vitreous. It is usually coloured grey or brownish because of impurities in the clay used for its manufacture, and is normally glazed."[12]

Porcelain

editPorcelain is a ceramic material made by heating materials, generally including kaolin, in a kiln to temperatures between 1,200 and 1,400 °C (2,200 and 2,600 °F). The toughness, strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises mainly from vitrification and the formation of the mineral mullite within the body at these high temperatures. Properties associated with porcelain include low permeability and elasticity; considerable strength, hardness, toughness, whiteness, translucency and resonance; and a high resistance to chemical attack and thermal shock. Porcelain has been described as being "completely vitrified, hard, impermeable (even before glazing), white or artificially coloured, translucent (except when of considerable thickness), and resonant". However, the term porcelain lacks a universal definition and has "been applied in a very unsystematic fashion to substances of diverse kinds which have only certain surface-qualities in common".[14]

Bone china

editBone china is a type of soft-paste porcelain that is composed of bone ash, feldspathic material, and kaolin. It has been defined as ware with a translucent body containing a minimum of 30% of phosphate derived from animal bone and calculated calcium phosphate.[12][clarification needed]

Developed by English potter Josiah Spode, bone china is known for its high levels of whiteness and translucency,[15] and very high mechanical strength and chip resistance.[16] Its high strength allows it to be produced in thinner cross-sections than other types of porcelain.[15] Like stoneware it is vitrified, but is translucent due to differing mineral properties.[17]

From its initial development and up to the later part of the twentieth century, bone china was almost exclusively an English product, with production being effectively localised in Stoke-on-Trent.[16]

Most major English firms made or still make it, including Mintons, Coalport, Spode, Royal Crown Derby, Royal Doulton, Wedgwood and Worcester. In the UK, references to "china" or "porcelain" can refer to bone china, and "English porcelain" has been used as a term for it, both in the UK and around the world.[18] Fine china is not necessarily bone china, and is a term used to refer to ware which does not contain bone ash.[12]

Surface treatments

editPainting

editChina painting, or porcelain painting is the decoration of glazed porcelain objects such as plates, bowls, vases or statues. The body of the object may be hard-paste porcelain, developed in China in the 7th or 8th century, or soft-paste porcelain (often bone china), developed in 18th-century Europe. The broader term ceramic painting includes painted decoration on lead-glazed earthenware such as creamware or tin-glazed pottery such as maiolica or faience. Typically the body is first fired in a kiln to convert it into a hard porous biscuit. Underglaze decoration may then be applied, followed by ceramic glaze, which is fired so it bonds to the body. The glazed porcelain may then be decorated with overglaze painting and fired again at a lower temperature to bond the paint with the glaze. Decoration may be applied by brush or by stenciling, transfer printing, lithography and screen printing.[19]

Slipware

editSlipware is a type of pottery identified by its primary decorating process where slip is placed onto the leather-hard clay body surface before firing by dipping, painting or splashing. Slip is an aqueous suspension of a clay body, which is a mixture of clays and other minerals such as quartz, feldspar and mica. A coating of white or coloured slip, known as an engobe, can be applied to the article to improve its appearance, to give a smoother surface to a rough body, mask an inferior colour or for decorative effect. Slips or engobes can also be applied by painting techniques, in isolation or in several layers and colours. Sgraffito involves scratching through a layer of coloured slip to reveal a different colour or the base body underneath. Several layers of slip and/or sgraffito can be done while the pot is still in an unfired state. One colour of slip can be fired, before a second is applied, and prior to the scratching or incising decoration. This is particularly useful if the base body is not of the desired colour or texture.[20]

Terra sigillata

editIn sharp contrast to the archaeological usage, in which the term terra sigillata refers to a whole class of pottery, in contemporary ceramic art, 'terra sigillata' describes only a watery refined slip used to facilitate the burnishing of raw clay surfaces and used to promote carbon smoke effects, in both primitive low temperature firing techniques and unglazed alternative western-style Raku firing techniques. Terra sigillata is also used as a brushable decorative colourant medium in higher temperature glazed ceramic techniques.[21]

Forms

editStudio pottery

editStudio pottery is pottery made by amateur or professional artists or artisans working alone or in small groups, making unique items or short runs. Typically, all stages of manufacture are carried out by the artists themselves.[22] Studio pottery includes functional wares such as tableware, cookware and non-functional wares such as sculpture. Studio potters can be referred to as ceramic artists, ceramists, ceramicists or as an artist who uses clay as a medium. Much studio pottery is tableware or cookware but an increasing number of studio potters produce non-functional or sculptural items. Some studio potters now prefer to call themselves ceramic artists, ceramists or simply artists. Studio pottery is represented by potters all over the world.

Tile

editA tile is a manufactured piece of hard-wearing material such as ceramic, stone, metal, or even glass, generally used for covering roofs, floors, walls, showers, or other objects such as tabletops. Alternatively, tile can sometimes refer to similar units made from lightweight materials such as perlite, wood, and mineral wool, typically used for wall and ceiling applications. In another sense, a "tile" is a construction tile or similar object, such as rectangular counters used in playing games (see tile-based game). The word is derived from the French word tuile, which is, in turn, from the Latin word tegula, meaning a roof tile composed of fired clay.

Tiles are often used to form wall murals and floor coverings, and can range from simple square tiles to complex mosaics. Tiles are most often made of ceramic, typically glazed for internal uses and unglazed for roofing, but other materials are also commonly used, such as glass, cork, concrete and other composite materials, and stone. Tiling stone is typically marble, onyx, granite or slate. Thinner tiles can be used on walls than on floors, which require more durable surfaces that will resist impacts.

Figurines

editA figurine (a diminutive form of the word figure) is a statuette that represents a human, deity, legendary creature, or animal. Figurines may be realistic or iconic, depending on the skill and intention of the creator. The earliest were made of stone or clay. In ancient Greece, many figurines were made from terracotta (see Greek terracotta figurines). Modern versions are made of ceramic, metal, glass, wood and plastic. Figurines and miniatures are sometimes used in board games, such as chess, and tabletop role playing games. Old figurines have been used to discount some historical theories, such as the origins of chess.

Tableware

editTableware is the dishes or dishware used for setting a table, serving food and dining. It includes cutlery, glassware, serving dishes and other useful items for practical as well as decorative purposes.[23][24] Dishes, bowls and cups may be made of ceramic, while cutlery is typically made from metal, and glassware is often made from glass or other non-ceramic materials. The quality, nature, variety and number of objects varies according to culture, religion, number of diners, cuisine and occasion. For example, Middle Eastern, Indian or Polynesian food culture and cuisine sometimes limits tableware to serving dishes, using bread or leaves as individual plates. Special occasions are usually reflected in higher quality tableware.[24]

Terracotta (artworks)

editIn addition to being a material, "terracotta" also refers to items made out of this material. In archaeology and art history, "terracotta" is often used to describe objects such as statues, and figurines not made on a potter's wheel. A prime example is the Terracotta Army, a collection of man-sized terracotta sculptures depicting the armies of Qin Shi Huang, the first Emperor of China. It is a form of funerary art buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE and whose purpose was to protect the emperor in his afterlife.[25]

French sculptor Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse made many terracotta pieces, but possibly the most famous is The Abduction of Hippodameia depicting the Greek mythological scene of a centaur kidnapping Hippodameia on her wedding day. American architect Louis Sullivan is well known for his elaborate glazed terracotta ornamentation, designs that would have been impossible to execute in any other medium. Terracotta and tile were used extensively in the town buildings of Victorian Birmingham, England.

History

editThere is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures, like that of the Nok in Africa over 3,000 years ago.[26] Cultures especially noted for ceramics include the Chinese, Cretan, Greek, Persian, Mayan, Japanese, and Korean cultures, as well as the modern Western cultures. There is evidence that pottery was independently invented in several regions of the world, including East Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, the Near East, and the Americas.

Paleolithic pottery (c. 20,000 BP)

editAlthough pottery figurines are found from earlier periods in Europe, the oldest pottery vessels come from East Asia, with finds in China and Japan, then still linked by a land bridge, and some in what is now the Russian Far East, providing several from 20,000 to 10,000 BCE, although the vessels were simple utilitarian objects.[30][31] Xianrendong Cave in Jiangxi province contained pottery fragments that date back to 20,000 years ago.[32][33] These early pottery containers were made well before the invention of agriculture, by mobile foragers who hunted and gathered their food during the Late Glacial Maximum.[28] Many of the pottery fragments had scorch marks, suggesting that the pottery was used for cooking.[28]

Before Neolithic pottery: stone containers (12,000–6,000 BC)

editMany remarkable containers were made from stone before the invention of pottery in Western Asia (which occurred around 7,000 BC), and before the invention of agriculture. The Natufian culture created elegant stone mortars during the period between 12,000 and 9,500 BC. Around 8000 BC, several early settlements became experts in crafting beautiful and highly sophisticated containers from stone, using materials such as alabaster or granite, and employing sand to shape and polish. Artisans used the veins in the material to maximize visual effect. Such object have been found in abundance on the upper Euphrates river, in what is today eastern Syria, especially at the site of Bouqras.[34] These form the early stages of the development of the Art of Mesopotamia.

-

Stone mortar from Eynan, Natufian period, 12,500-9,500 BC

-

Calcite tripod vase, mid-Euphrates, probably from Tell Buqras, 6,000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 31551

-

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6,500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Alabaster pot, Mid-Euphrates region, 6,500 BC, Louvre Museum

Neolithic pottery (6,500–3,500 BC)

editEarly pots were made by what is known as the "coiling" method, which worked the clay into a long string that wound to form a shape that later made smooth walls. The potter's wheel was probably invented in Mesopotamia by the 4th millennium BCE, but spread across nearly all Eurasia and much of Africa, though it remained unknown in the New World until the arrival of Europeans. Decoration of the clay by incising and painting is found very widely, and was initially geometric, but often included figurative designs from very early on.

So important is pottery to the archaeology of prehistoric cultures that many are known by names taken from their distinctive, and often very fine, pottery, such as the Linear Pottery culture, Beaker culture, Globular Amphora culture, Corded Ware culture and Funnelbeaker culture, to take examples only from Neolithic Europe (approximately 7000–1800 BCE).

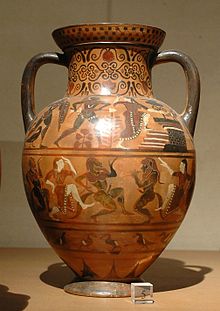

Ceramic art has generated many styles from its own tradition, but is often closely related to contemporary sculpture and metalwork. Many times in its history styles from the usually more prestigious and expensive art of metalworking have been copied in ceramics. This can be seen in early Chinese ceramics, such as pottery and ceramic-wares of the Shang dynasty, in Ancient Roman and Iranian pottery, and Rococo European styles, copying contemporary silverware shapes. A common use of ceramics is for "pots" - containers such as bowls, vases and amphorae, as well as other tableware, but figurines have been very widely made.

Ceramics as wall decoration

editThe earliest evidence of glazed brick is the discovery of glazed bricks in the Elamite Temple at Chogha Zanbil, dated to the 13th century BCE. Glazed and coloured bricks were used to make low reliefs in Ancient Mesopotamia, most famously the Ishtar Gate of Babylon (c. 575 BCE), now partly reconstructed in Berlin, with sections elsewhere. Mesopotamian craftsmen were imported for the palaces of the Persian Empire such as Persepolis. The tradition continued, and after the Islamic conquest of Persia coloured and often painted glazed bricks or tiles became an important element in Persian architecture, and from there spread to much of the Islamic world, notably the İznik pottery of Turkey under the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Using the lusterware technology, one of the finest examples of medieval Islamic use of ceramics as wall decoration can be seen in the Mosque of Uqba also known as the Great Mosque of kairouan (in Tunisia), the upper part of the mihrab wall is adorned with polychrome and monochrome lusterware tiles; dating from 862 to 863, these tiles were most probably imported from Mesopotamia.[35][36]

Transmitted via Islamic Iberia, a new tradition of Azulejos developed in Spain and especially Portugal, which by the Baroque period produced extremely large painted scenes on tiles, usually in blue and white. Delftware tiles, typically with a painted design covering only one (rather small) tile, were ubiquitous in the Netherlands and widely exported over Northern Europe from the 16th century on. Several 18th-century royal palaces had porcelain rooms with the walls entirely covered in porcelain. Surviving examples include ones at Capodimonte, Naples, the Royal Palace of Madrid and the nearby Royal Palace of Aranjuez.[37] Elaborate cocklestoves were a feature of rooms of the middle and upper-classes in Northern Europe from the 17th to 19th centuries.

There are several other types of traditional tiles that remain in manufacture, for example, the small, almost mosaic, brightly coloured zellige tiles of Morocco. With exceptions, notably the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing, tiles or glazed bricks do not feature largely in East Asian ceramics.

Regional developments

editAlthough pottery figurines are found from earlier periods in Europe, the oldest pottery vessels come from East Asia, with finds in China and Japan, then still linked by a land bridge, and some in what is now the Russian Far East, providing several from between 20,000 and 10,000 BCE, although the vessels were simple utilitarian objects.[30][31] Xianrendong Cave in Jiangxi province contained pottery fragments that date back to 20,000 years ago.[32][33]

Cambodia

editRecent archaeological excavations at Angkor Borei (in southern Cambodia) have recovered a large number of ceramics, some of which probably date back to the prehistoric period. Most of the pottery, however, dates to the pre-Angkorian period and consists mainly of pinkish terracotta pots which were either hand-made or thrown on a wheel, and then decorated with incised patterns.

Glazed wares first appear in the archaeological record at the end of the 9th century at the Roluos temple group in the Angkor region, where green-glazed pot shards have been found. A brown glaze became popular at the beginning of the 11th century and brown-glazed wares have been found in abundance at Khmer sites in northeast Thailand. Decorating pottery with animal forms was a popular style from the 11th to 13th century. Archaeological excavations in the Angkor region have revealed that towards the end of Angkor period production of indigenous pottery declined while there was a dramatic increase in Chinese ceramic imports.

Direct evidence of the shapes of vessels is provided by scenes depicted on bas-reliefs at Khmer temples, which also offer insight into domestic and ritualistic uses of the wares. The wide range of utilitarian shapes suggest the Khmers used ceramics in their daily life for cooking, food preservation, carrying and storing liquids, as containers for medicinal herbs, perfumes and cosmetics.[38]

China

editThere is Chinese porcelain from the late Eastern Han period (100–200 CE), the Three Kingdoms period (220–280 CE), the Six Dynasties period (220–589 CE), and thereafter. China in particular has had a continuous history of large-scale production, with the Imperial factories usually producing the best work. The Tang dynasty (618 to 906 CE) is especially noted for grave goods figures of humans, animals and model houses, boats and other goods, excavated (usually illegally) from graves in large numbers.

Some experts believe the first true porcelain was made in the province of Zhejiang in China during the Eastern Han period. Shards recovered from archaeological Eastern Han kiln sites estimated firing temperature ranged from 1,260 to 1,300 °C (2,300 to 2,370 °F).[40] As far back as 1000 BCE, the so-called "porcelaneous wares" or "proto-porcelain wares" were made using at least some kaolin fired at high temperatures. The dividing line between the two and true porcelain wares is not a clear one. Archaeological finds have pushed the dates to as early as the Han dynasty (206–BCE – 220 CE).[41]

The Imperial porcelain of the Song dynasty (960–1279), featuring very subtle decoration shallowly carved by knife in the clay, is regarded by many authorities as the peak of Chinese ceramics, though the large and more exuberantly painted ceramics of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) have a wider reputation.

Chinese emperors gave ceramics as diplomatic gifts on a lavish scale, and the presence of Chinese ceramics no doubt aided the development of related traditions of ceramics in Japan and Korea in particular.

Until the 16th century, small quantities of expensive Chinese porcelain were imported into Europe. From the 16th century onwards attempts were made to imitate it in Europe, including soft-paste and the Medici porcelain made in Florence. None was successful until a recipe for hard-paste porcelain was devised at the Meissen factory in Dresden in 1710. Within a few years, porcelain factories sprung up at Nymphenburg in Bavaria (1754) and Capodimonte in Naples (1743) and many other places, often financed by a local ruler.

Japan

editThe earliest Japanese pottery was made around the 11th millennium BCE. Jōmon ware emerged in the 6th millennium BCE and the plainer Yayoi style in about the 4th century BCE. This early pottery was soft earthenware, fired at low temperatures. The potter's wheel and a kiln capable of reaching higher temperatures and firing stoneware appeared in the 3rd or 4th centuries CE, probably brought from China via the Korean peninsula.[42] In the 8th century, official kilns in Japan produced simple, green lead-glazed earthenware. Unglazed stoneware was used as funerary jars, storage jars and kitchen pots up to the 17th century. Some of the kilns improved their methods and are known as the “Six Old Kilns”. From the 11th to the 16th century, Japan imported much porcelain from China and some from Korea. The Japanese overlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi's attempts to conquer China in the 1590s were dubbed the "Ceramic Wars";[citation needed] the emigration of Korean potters appeared to be a major cause. One of these potters, Yi Sam-pyeong, discovered the raw material of porcelain in Arita and produced first true porcelain in Japan.

In the 17th century, conditions in China drove some of its potters into Japan, bringing with them the knowledge to make refined porcelain. From the mid-century, the Dutch East India Company began to import Japanese porcelain into Europe. At this time, Kakiemon wares were produced at the factories of Arita, which had much in common with the Chinese Famille Verte style. The superb quality of its enamel decoration was highly prized in the West and widely imitated by the major European porcelain manufacturers. In 1971 it was declared an important "intangible cultural treasure" by the Japanese government.

In the 20th century, interest in the art of the village potter was revived by the Mingei folk movement led by potters Shoji Hamada, Kawai Kajiro and others. They studied traditional methods in order to preserve native wares that were in danger of disappearing. Modern masters use ancient methods to bring pottery and porcelain to new heights of achievement at Shiga, Iga, Karatsu, Hagi, and Bizen. A few outstanding potters were designated living cultural treasures (mukei bunkazai 無形文化財). In the old capital of Kyoto, the Raku family continued to produce the rough tea bowls that had so delighted connoisseurs. At Mino, potters continued to reconstruct the classic formulas of Momoyama-era Seto-type tea wares of Mino, such as Oribe ware. By the 1990s many master potters worked away from ancient kilns and made classic wares in all parts of Japan.

Korea

editKorean pottery has had a continuous tradition since simple earthenware from about 8000 BCE. Styles have generally been a distinctive variant of Chinese, and later Japanese, developments. The celadon Goryeo ware from the Goryeo dynasty (918–1392) and early Joseon white porcelain of the following dynasty are generally regarded as the finest achievements.[43]

Western Asia and the Middle East

editIslamic pottery

editFrom the 8th to 18th centuries, glazed ceramics was important in Islamic art, usually in the form of elaborate pottery,[44] developing on vigorous Persian and Egyptian pre-Islamic traditions in particular. Tin-opacified glazing was developed by the Islamic potters, the first examples found as blue-painted ware in Basra, dating from about the 8th century. The Islamic world had contact with China, and increasingly adapted many Chinese decorative motifs. Persian wares gradually relaxed Islamic restrictions on figurative ornament, and painted figuratives scenes became very important.

Stoneware was also an important craft in Islamic pottery, produced throughout Iraq and Syria by the 9th century.[45] Pottery was produced in Raqqa, Syria, in the 8th century.[46] Other centers for innovative ceramics in the Islamic world were Fustat (near modern Cairo) from 975 to 1075, Damascus from 1100 to around 1600 and Tabriz from 1470 to 1550.[47]

The albarello form, a type of maiolica earthenware jar originally designed to hold apothecaries' ointments and dry drugs, was first made in the Islamic Middle East. It was brought to Italy by Hispano-Moresque traders; the earliest Italian examples were produced in Florence in the 15th century.

Iznik pottery, made in western Anatolia, is highly decorated ceramics whose heyday was the late 16th century under the Ottoman sultans. Iznik vessels were originally made in imitation of Chinese porcelain, which was highly prized. Under Süleyman the Magnificent (1520–66), demand for Iznik wares increased. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman sultans started a programme of building, which used large quantities of Iznik tiles. The Sultan Ahmed Mosque in Istanbul (built 1609–16) alone contains 20,000 tiles and tiles were used extensively in the Topkapi Palace (commenced 1459). As a result of this demand, tiles dominated the output of the Iznik potteries.

Europe

editEarly figurines

editThe earliest known ceramic objects are the Gravettian figurines from the Upper Paleolithic period, such as those discovered at Dolní Věstonice in the modern-day Czech Republic. The Venus of Dolní Věstonice (Věstonická Venuše in Czech) is a statuette of a nude female figure dating from some time from 29,000–25,000 BCE.[48] It was made by moulding and then firing a mixture of clay and powdered bone.[49] Similar objects in various media found throughout Europe and Asia and dating from the Upper Paleolithic period have also been called Venus figurines. Scholars are not agreed as to their purpose or cultural significance.

The ancient Mediterranean

editGlazed Egyptian faience dates to the third millennium BCE), with painted but unglazed pottery used even earlier during the predynastic Naqada culture. Faience became sophisticated and produced on a large scale, using moulds as well modelling, and later also throwing on the wheel. Several methods of glazing were developed, but colours remained largely limited to a range in the blue-green spectrum.

On the Greek island of Santorini are some of the earliest finds created by the Minoans dating to the third millennium BCE, with the original settlement at Akrotiri dating to the fourth millennium BCE;[50] excavation work continues at the principal archaeological site of Akrotiri. Some of the excavated homes contain huge ceramic storage jars known as pithoi.

Ancient Greek and Etruscan ceramics are renowned for their figurative painting, especially in the black-figure and red-figure styles. Moulded Greek terracotta figurines, especially those from Tanagra, were small figures, often religious but later including many of everyday genre figures, apparently used purely for decoration.

Ancient Roman pottery, such as Samian ware, was rarely as fine, and largely copied shapes from metalwork, but was produced in enormous quantities, and is found all over Europe and the Middle East, and beyond. Monte Testaccio is a waste mound in Rome made almost entirely of broken amphorae used for transporting and storing liquids and other products. Few vessels of great artistic interest have survived, but there are very many small figures, often incorporated into oil lamps or similar objects, and often with religious or erotic themes (or both together – a Roman speciality). The Romans generally did not leave grave goods, the best source of ancient pottery, but even so they do not seem to have had much in the way of luxury pottery, unlike Roman glass, which the elite used with gold or silver tableware. The more expensive pottery tended to use relief decoration, often moulded, rather than paint. Especially in the Eastern Empire, local traditions continued, hybridizing with Roman styles to varying extents.

Tin-glazed pottery

editTin-glazed pottery, or faience, originated in Iraq in the 9th century, from where it spread to Egypt, Persia and Spain before reaching Italy in the Renaissance, Holland in the 16th century and England, France and other European countries shortly after. Important regional styles in Europe include: Hispano-Moresque, maiolica, Delftware, and English Delftware. By the High Middle Ages the Hispano-Moresque ware of Al-Andalus was the most sophisticated pottery being produced in Europe, with elaborate decoration. It introduced tin-glazing to Europe, which was developed in the Italian Renaissance in maiolica. Tin-glazed pottery was taken up in the Netherlands from the 16th to the 18th centuries, the potters making household, decorative pieces and tiles in vast numbers,[51] usually with blue painting on a white ground. Dutch potters took tin-glazed pottery to the British Isles, where it was made between about 1550 and 1800. In France, tin-glaze was begun in 1690 at Quimper in Brittany,[52] followed in Rouen, Strasbourg and Lunéville. The development of white, or near white, firing bodies in Europe from the late 18th century, such as Creamware by Josiah Wedgwood and porcelain, reduced the demand for Delftware, faience and majolica. Today, tin oxide usage in glazes finds limited use in conjunction with other, lower cost opacifying agents, although it is generally restricted to specialist low temperature applications and use by studio potters,[53][54] including Picasso who produced pottery using tin glazes.

Porcelain

editUntil the 16th century, small quantities of expensive Chinese porcelain were imported into Europe. From the 16th century onwards attempts were made to imitate it in Europe, including soft-paste and the Medici porcelain made in Florence. In 1712, many of the elaborate Chinese porcelain manufacturing secrets were revealed throughout Europe by the French Jesuit father Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles and soon published in the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses de Chine par des missionnaires jésuites[55] After much experimentation, a recipe for hard-paste porcelain was devised at the Meissen porcelain factory in Dresden soon after 1710, and was on sale by 1713. Within a few decades, porcelain factories sprung up at Nymphenburg in Bavaria (1754) and Capodimonte in Naples (1743) and many other places, often financed by a local ruler.

Soft-paste porcelain was made at Rouen in the 1680s, but the first important production was at St.Cloud, letters-patent being granted in 1702. The Duc de Bourbon established a soft-paste factory, the Chantilly porcelain, in the grounds of his Château de Chantilly in 1730; a soft-paste factory was opened at Mennecy; and the Vincennes factory was set up by workers from Chantilly in 1740, moving to larger premises at Sèvres[56][57] in 1756. The superior soft-paste made at Sèvres put it in the leading position in Europe in the second half of the 18th century.[58] The first soft-paste in England was demonstrated in 1742, apparently based on the Saint-Cloud formula. In 1749 a patent was taken out on the first bone china, subsequently perfected by Josiah Spode. The main English porcelain makers in the 18th century were at Chelsea, Bow, St James's, Bristol, Derby and Lowestoft.

Porcelain was ideally suited to the energetic Rococo curves of the day. The products of these early decades of European porcelain are generally the most highly regarded, and expensive. The Meissen modeler Johann Joachim Kaendler and Franz Anton Bustelli of Nymphenburg are perhaps the most outstanding ceramic artists of the period. Like other leading modelers, they trained as sculptors and produced models from which moulds were taken.

By the end of the 18th century owning porcelain tableware and decorative objects had become obligatory among the prosperous middle-classes of Europe, and there were factories in most countries, many of which are still producing. As well as tableware, early European porcelain revived the taste for purely decorative figures of people or animals, which had also been a feature of several ancient cultures, often as grave goods. These were still being produced in China as blanc de Chine religious figures, many of which had reached Europe. European figures were almost entirely secular, and soon brightly and brilliantly painted, often in groups with a modelled setting, and a strong narrative element (see picture).

Wedgwood and the North Staffordshire Potteries

editFrom the 17th century, Stoke-on-Trent in North Staffordshire emerged as a major centre of pottery making.[59] Important contributions to the development of the industry were made by the firms of Wedgwood, Spode, Royal Doulton and Minton.

The local presence of abundant supplies of coal and suitable clay for earthenware production led to the early but at first limited development of the local pottery industry. The construction of the Trent and Mersey Canal allowed the easy transportation of china clay from Cornwall together with other materials and facilitated the production of creamware and bone china. Other production centres had a lead in the production of high quality wares but the preeminence of North Staffordshire was brought about by methodical and detailed research and a willingness to experiment carried out over many years, initially by one man, Josiah Wedgwood. His lead was followed by other local potters, scientists and engineers.

Wedgwood is credited with the industrialization of the manufacture of pottery. His work was of very high quality: when visiting his workshop, if he saw an offending vessel that failed to meet with his standards, he would smash it with his stick, exclaiming, "This will not do for Josiah Wedgwood!" He was keenly interested in the scientific advances of his day and it was this interest that underpinned his adoption of its approach and methods to revolutionize the quality of his pottery. His unique glazes began to distinguish his wares from anything else on the market. His matt finish jasperware in two colours was highly suitable for the Neoclassicism of the end of the century, imitating the effects of Ancient Roman carved gemstone cameos like the Gemma Augustea, or the cameo glass Portland Vase, of which Wedgwood produced copies.

He also is credited with perfecting transfer-printing, first developed in England about 1750. By the end of the century this had largely replaced hand-painting for complex designs, except at the luxury end of the market, and the vast majority of the world's decorated pottery uses versions of the technique to the present day. The perfecting of underglaze transfer printing is widely credited to Josiah Spode the first. The process had been used as a development from the processes used in book printing, and early paper quality made a very refined detail in the design incapable of reproduction, so early print patterns were rather lacking in subtlety of tonal variation. The development of machine made thinner printing papers around 1804 allowed the engravers to use a much wider variety of tonal techniques which became capable of being reproduced on the ware, much more successfully.

Far from perfecting underglaze print Wedgwood was persuaded by his painters not to adopt underglaze printing until it became evident that Mr Spode was taking away his business through competitive pricing for a much more heavily decorated high quality product.

Stoke-on-Trent's supremacy in pottery manufacture nurtured and attracted a large number of ceramic artists including Clarice Cliff, Susie Cooper, Lorna Bailey, Charlotte Rhead, Frederick Hurten Rhead and Jabez Vodrey.

Studio pottery in Britain

editStudio pottery is made by artists working alone or in small groups, producing unique items or short runs, typically with all stages of manufacture carried out by one individual.[22] It is represented by potters all over the world but has strong roots in Britain, with potters such as Bernard Leach, William Staite Murray, Dora Billington, Lucie Rie and Hans Coper. Bernard Leach (1887–1979) established a style of pottery influenced by Far-Eastern and medieval English forms. After briefly experimenting with earthenware, he turned to stoneware fired to high temperatures in large oil- or wood-burning kilns. This style dominated British studio pottery in the mid-20th-century. The Austrian refugee Lucie Rie (1902–1995) has been regarded as essentially a modernist who experimented with new glaze effects on often brightly coloured bowls and bottles. Hans Coper (1920–1981) produced non-functional, sculptural and unglazed pieces. After the Second World War, studio pottery in Britain was encouraged by the wartime ban on decorating manufactured pottery and the modernist spirit of the Festival of Britain. The simple, functional designs chimed in with the modernist ethos. Several potteries were formed in response to this fifties boom, and this style of studio pottery remained popular into the nineteen-seventies.[60] Elizabeth Fritsch (1940-) took up ceramics working under Hans Coper at the Royal College of Art (1968–1971). Fritsch was one of a group of outstanding ceramicists who emerged from the Royal College of Art at that time. Fritschs' ceramic vessels broke away from traditional methods and she developed a hand built flattened coil technique in stoneware smoothed and refined into accurately profiled forms. They are then hand painted with dry matt slips, in colours unusual for ceramics.

Pottery in Germany

editGerman pottery has its roots in the alchemistry laboratories searching for gold production.

Pottery in Austria

editIn 1718 a pottery was founded in Vienna.[62]

Pottery in Russia

editThe Imperial Porcelain Manufacture was founded in 1744 in Oranienbaum, Russia.[63] It was based on the invention of porcelain by D. I. Winogradow (independent from Böttgers invention 1708, Dresden). An important collection of antique porcelain is preserved in the Russian Museum of Ceramics.

The Americas

editNative American pottery

editThe people in North, Central, and South America continents had a wide variety of pottery traditions before Europeans arrived. The oldest ceramics known in the Americas—made from 5,000 to 6,000 years ago—are found in the Andean region, along the Pacific coast of Ecuador at Valdivia and Puerto Hormiga, and in the San Jacinto Valley of Colombia; objects from 3,800 to 4,000 years old have been discovered in Peru. Some archaeologists believe that ceramics know-how found its way by sea to Mesoamerica, the second great cradle of civilization in the Americas.[64]

The best-developed styles found in the central and southern Andes are the ceramics found near the ceremonial site at Chavín de Huántar (800–400 BCE) and Cupisnique (1000–400 BCE). During the same period, another culture developed on the southern coast of Peru, in the area called Paracas. The Paracas culture (600–100 BCE) produced marvelous works of embossed ceramic finished with a thick oil applied after firing. This colorful tradition in ceramics and textiles was followed by the Nazca culture (1–600 CE), whose potters developed improved techniques for preparing clay and for decorating objects, using fine brushes to paint sophisticated motifs. In the early stage of Nazca ceramics, potters painted realistic characters and landscapes.

The Moche cultures (1–800 CE) that flourished on the northern coast of modern Peru produced modelled clay sculptures and effigies decorated with fine lines of red on a beige background. Their pottery stands out for its huacos portrait vases, in which human faces are shown expressing different emotions—happiness, sadness, anger, melancholy—as well for its complicated drawings of wars, human sacrifices, and celebrations.[65]

The Maya were relative latecomers to ceramic development, as their ceramic arts flourished in the Maya Classic Period, or the 2nd to 10th century. One important site in southern Belize is known as Lubaantun, that boasts particularly detailed and prolific works. As evidence of the extent to which these ceramic art works were prized, many specimens traced to Lubaantun have been found at distant Maya sites in Honduras and Guatemala.[66] Furthermore, the current Maya people of Lubaantun continue to hand produce copies of many of the original designs found at Lubaantun.

In the United States, the oldest pottery dates to 2500 BCE. It has been found in the Timucuan Ecological and Historic Preserve in Jacksonville, Florida, and some slightly older along the Savannah River in Georgia.[67]

The Hopi in Northern Arizona and several other Puebloan peoples including the Taos, Acoma, and Zuñi people (all in the Southwestern United States) are renowned for painted pottery in several different styles. Nampeyo[68] and her relatives created pottery that became highly sought after beginning in the early 20th century. Pueblo tribes in the state of New Mexico have styles distinctive to each of the various pueblos (villages). They include Santa Clara Pueblo, Taos Pueblo, Hopi Pueblos, San Ildefonso Pueblo, Acoma Pueblo and Zuni Pueblo, amongst others. Some of the renowned artists of Pueblo pottery include: Nampeyo, Elva Nampeyo, and Dextra Quotskuyva of the Hopi; Leonidas Tapia of San Juan Pueblo; and Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez of San Ildefonso Pueblo. In the early 20th century Martinez and her husband Julian rediscovered the method of creating traditional San Ildefonso Pueblo Black-on Black pottery.

Mexican ceramics

editMexican ceramics are an ancient tradition. Precolumbian potters built up their wares with pinching, coiling, or hammer-an-anvil methods and, instead of using glaze, burnished their pots.

Studio pottery in the United States

editThere is a strong tradition of studio artists working in ceramics in the United States. It had a period of growth in the 1960s and continues to present times. Many fine art, craft, and contemporary art museums have pieces in their permanent collections. Beatrice Wood was an American artist and studio potter located in Ojai, California. She developed a unique form of luster-glaze technique, and was active from the 1930s to her death in 1998 at 105 years old. Robert Arneson created larger sculptural work, in an abstracted representational style. There are ceramics arts departments at many colleges, universities, and fine arts institutes in the United States.

Sub-Saharan Africa

editIt appears that pottery was independently developed in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 10th millennium BC, with findings dating to at least 9,400 BC from central Mali.[69] In Africa, the earliest pottery has been found in the large mountain massifs of the Central Sahara, in the Eastern Sahara, and the Nile Valley, dating back to between the ninth and tenth millennium.[70]

Pottery in Sub-Saharan Africa is traditionally made by coiling and is fired at low temperature. The figurines of the ancient Nok culture, whose function remains unclear, are an example of high-quality figural work, found in many cultures, such as the Benin of Nigeria.

In the Aïr Region of Niger (West Africa) (Haour 2003) pottery dating from around 10,000 BCE was excavated.[71]

Ladi Kwali, a Nigerian potter who worked in the Gwari tradition, made large pots decorated with incised patterns. Her work is an interesting hybrid of traditional African with western studio pottery. Magdalene Odundo is a Kenyan-born British studio potter whose ceramics are hand built and burnished.

Ceramics museums and museum collections

editA ceramics museum is a museum wholly or largely devoted to ceramics, normally ceramic artworks, whose collections may include glass and enamel as well, but will usually concentrate on pottery, including porcelain. Most national ceramics collections are in a more general museum covering all the arts, or just the decorative arts, but there are a number of specialized ceramics museums, some concentrating on the production of just one country, region or manufacturer. Others have international collections, which may concentrate on ceramics from Europe or East Asia, or have global coverage.

In Asian and Islamic countries ceramics are usually a strong feature of general and national museums.[citation needed] Also most specialist archaeological museums, in all countries, have large ceramics collections, as pottery is the commonest type of archaeological artifact.[72] Most of these are broken shards however.

Outstanding major ceramics collections in general museums include The Palace Museum, Beijing, with 340,000 pieces,[73] and the National Palace Museum in Taipei city, Taiwan (25,000 pieces);[74] both are mostly derived from the Chinese Imperial collection, and are almost entirely of pieces from China. In London, the Victoria and Albert Museum (over 75,000 pieces, mostly after 1400 CE) and British Museum (mostly before 1400 CE) have very strong international collections. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and Freer Gallery of Art in Washington DC (thousands, all Asian[75]) have perhaps the best of the many fine collections in the large city museums of the United States. The Corning Museum of Glass, in Corning, New York, has more than 45,000 glass objects. Museo internazionale delle ceramiche in Faenza, Italy, is the nation's largest collection of ceramics artworks, with 60,000 pieces.[76]

-

100 BCE – 250 CE

-

Ceramic goblet from Navdatoli, Malwa, India, 1300 BCE; Malwa culture

-

A funerary urn in the shape of a "bat god" or a jaguar, from Oaxaca, Mexico, dated to 300–650 CE. Height: 9.5 in (23 cm).

-

Luca della Robbia the Young, Virgin and Child with John the Baptist

See also

edit- American Museum of Ceramic Art – ceramic Art Museum in Pomona, California

- List of studio potters

- Sculpture – Artworks that are three-dimensional objects

- Visual arts – Art forms involving visual perception

References

editCitations

edit- ^ "Art Pottery Manufacturers and Collectors". Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2003.

- ^ "California Art Pottery, 1895-1920" Scholar Works, California State University

- ^ The Webster Encyclopedic Dictionary

- ^ "Earthenware" Britannica online

- ^ OED, "Terracotta"

- ^ 'Diagnosis Of Terra-Cotta Glaze Spalling.' S.E. Thomasen, C.L. Searls. Masonry: Materials, Design, Construction and Maintenance. ASTM STP 992 Philadelphia, USA, 1988. American Society for Testing & Materials.

- ^ 'Colour Degradation In A Terra Cotta Glaze' H.J. Lee, W.M. Carty, J.Gill. Ceram.Eng.Sci.Proc. 21, No.2, 2000, p. 45–58.

- ^ 'High-lead glaze compositions and alterations: example of byzantine tiles.' A. Bouquillon. C. Pouthas. Euro Ceramics V. Pt.2. Trans Tech Publications, Switzerland,1997, p. 1487–1490 Quote: "A collection of architectural Byzantine tiles in glazed terra cotta is stored and exhibited in the Art Object department of the Louvre Museum as well as in the Musee de la Ceramique de Sevres."

- ^ 'Industrial Ceramics.' F.Singer, S.S.Singer. Chapman & Hall. 1971. Quote: "The lighter pieces that are glazed may also be termed 'terracotta.'

- ^ Standard Terminology of Ceramic Whiteware and Related Products: ASTM Standard C242.

- ^ "What Temperature Should I Fire My Clay To?". bigceramicstore.com. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ a b c d Dodd 1994.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Jasperware is unglazed stoneware

- ^ Definition in The Combined Nomenclature of the European Communities defines, Burton, 1906

- ^ a b Ozgundogdu, Feyza Cakir. "Bone China from Turkey" Ceramics Technical; May2005, Issue 20, p 29–32.

- ^ a b 'Trading Places.' R.Ware. Asian Ceramics. November, 2009, p.35,37-39.

- ^ What is China? As with stoneware, the body becomes vitrified; which means the body fuses, becomes nonabsorbent, and very strong. Unlike stoneware, china becomes very white and translucent. Archived 14 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Osborne, Harold (ed), The Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts, p. 130, 1975, OUP, ISBN 0-19-866113-4; Faulkner, Charles H., "The Ramseys at Swan Pond: The Archaeology and History of an East Tennessee Farm, p.96, 2008, Univ. of Tennessee Press, 2008, ISBN 1-57233-609-9, 9781572336094; Lawrence, Susan, "Archaeologies of the British: Explorations of Identity in the United Kingdom and Its Colonies 1600–1945", p. 196, 2013, Routledge, ISBN 1-136-80192-8, 781136801921

- ^ Lewis, Florence (1883). China painting. Cassell.

- ^ Eden, Victoria and Michael. (1999) Slipware, Contemporary Approaches. A & C Black, University of Pennsylvania Press, G & B Arts International. ISBN 90-5703-212-0

- ^ Garbsch, Jochen, Terra Sigillata. (1982) Ein Weltreich im Spiegel seines Luxusgeschirrs, Munich. (in German)

- ^ a b Cooper 2010.

- ^ Bloomfield, Linda (2013). Contemporary tableware. London: A. & C. Black. ISBN 978-1-4081-5395-6.

- ^ a b Venable, Charles L.; et al. (2000). China and Glass in America, 1880–1980: From Table Top to TV Tray. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-6692-5.

- ^ Portal, Jane (2007). The First Emperor: China's Terracotta Army. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02697-1.

- ^ Breunig, Peter. 2014. Nok: African Sculpture in Archaeological Context: p. 21.

- ^ Huan, Anthony (13 April 2019). "Ancient China: Neolithic". National Museum of China.

- ^ a b c Bar-Yosef, Ofer; Arpin, Trina; Pan, Yan; Cohen, David; Goldberg, Paul; Zhang, Chi; Wu, Xiaohong (29 June 2012). "Early Pottery at 20,000 Years Ago in Xianrendong Cave, China". Science. 336 (6089): 1696–1700. Bibcode:2012Sci...336.1696W. doi:10.1126/science.1218643. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22745428. S2CID 37666548.

- ^ Marshall, Michael (2012). "Oldest pottery hints at cooking's ice-age origins". New Scientist. 215 (2872): 14. Bibcode:2012NewSc.215Q..14M. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(12)61728-X.

- ^ a b "BBC NEWS – Science & Environment – 'Oldest pottery' found in China". bbc.co.uk. June 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ a b Boaretto, E.; et al. (2009). "Radiocarbon dating of charcoal and bone collagen associated with early pottery at Yuchanyan Cave, Hunan Province, China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 106 (24): 9537–9538. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.9595B. doi:10.1073/pnas.0900539106. PMC 2689310. PMID 19487667.

- ^ a b "Harvard, BU researchers find evidence of 20,000-year-old pottery". Boston.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ a b Stanglin, Douglas (29 June 2012). "Pottery found in China cave confirmed as world's oldest". USA Today.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Hess, Catherine; Komaroff, Linda; Saliba, George (27 December 2004). The Arts of Fire: Islamic Influences on Glass and Ceramics of the Italian Renaissance. Getty Publications. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-89236-758-0 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Qantara – Mihrāb of the Great Mosque of Kairouan". qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Porcelain Room, Aranjuez Comprehensive but shaky video [dead link]

- ^ "Contact Support". cambodiamuseum.info. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "Celadon". Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007.

- ^ He Li, (1996). Chinese Ceramics. The New Standard Guide. Thames and Hudson, London. ISBN 0-500-23727-1.

- ^ Temple, Robert K.G. (2007). The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (3rd edition). London: André Deutsch, pp. 103–6. ISBN 978-0-233-00202-6

- ^ The Metropolitan Museum of Art [1] "Although the roots of Sueki reach back to ancient China, its direct precursor is the grayware of the Three Kingdoms period in Korea."

- ^ "Collection: Korean Art". Freer/Sackler. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 1 September 2015. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Mason, Robert B. (1995). New Looks at Old Pots: Results of Recent Multidisciplinary Studies of Glazed Ceramics from the Islamic World. Vol. XII. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-10314-6.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) Mason (1995), p. 1 - ^ Mason (1995), p. 5

- ^ Henderson, J.; McLoughlin, S. D.; McPhail, D. S. (2004). "Radical changes in Islamic glass technology: evidence for conservatism and experimentation with new glass recipes from early and middle Islamic Raqqa, Syria". Archaeometry. 46 (3): 439–68. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00167.x.

- ^ Mason (1995), p. 7

- ^ "No. 359: The Dolni Vestonice Ceramics". uh.edu. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Chris Stringer. Homo Britannicus, Alan Lane, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7139-9795-8.

- ^ "Archaeological site of akrotiri Santorini Greece". travel-to-santorini.com. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Caiger-Smith, Alan, Tin Glazed Pottery, Faber and Faber, 1973

- ^ "สล็อตเว็บตรง เว็บแท้ไม่มีขั้นต่ำ รวมเกมสล็อตแตกง่ายทุกค่าย". Archived from the original on 13 April 2005.

- ^ 'Ceramic Glazes.' F.Singer & W.L.German. Borax Consolidated Limited. London. 1960.

- ^ 'Ceramics Glaze Technology.' J.R. Taylor & A.C. Bull. The Institute Of Ceramics & Pergamon Press. Oxford. 1986.

- ^ Baghdiantz McAbe, Ina (2008). Orientalism in Early Modern France. Oxford: Berg Publishing, p. 220. ISBN 978-1-84520-374-0; Finley, Robert (2010). The pilgrim art. Cultures of porcelain in world history. University of California Press, p. 18. ISBN 978-0-520-24468-9; Kerr, R. & Wood, N. (2004). Joseph Needham : Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5 Chemistry and Chemical Technology : Part 12 Ceramic Technology. Cambridge University Press, p. 36-7. ISBN 0-521-83833-9

- ^ "The 18th Century: The Rise and Success". Manufacture nationale de Sèvres. Archived from the original on 24 November 2006.

- ^ "Sèvres Porcelain in the Nineteenth Century". The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "French Porcelain in the Eighteenth Century". The Met's Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "all about Stoke-on-Trent in 5 minutes..." thepotteries.org. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Harrod, Tanya, "From A Potter's Book to The Maker's Eye: British Studio Ceramics 1940–1982", in The Harrow Connection, Northern Centre for Contemporary Art, 1989

- ^ "HISTORY Porzellan Manufaktur Nymphenburg". Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ "Porcelain Museum in the Augarten". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ "Imperial Porcelain: The History of Russian Imperial Porcelain from 1744 to 1917*". Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ^ The New York Times, Art Review Museum of American Indian's 'Born of Clay' Explores Culture Through Ceramics By GRACE GLUECK, Published: 1 July 2006

- ^ Born of Clay – Ceramic from the National Museum of the American Indian, 2005 Smithsonian Institution

- ^ C.M. Hogan, Comparison of Mayan sites in southern and western Belize, Lumina Technologies (2006)

- ^ Soergel, Matt (18 October 2009). "The Mocama: New name for an old people". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- ^ A Nampeyo Showcase Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, a display of some of Nampeyo's work

- ^ Simon Bradley, A Swiss-led team of archaeologists has discovered pieces of the oldest African pottery in central Mali, dating back to at least 9,400BC Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, SWI swissinfo.ch – the international service of the Swiss Broadcasting Corporation (SBC), 18 January 2007

- ^ Jesse, Friederike (25 October 2010). "Early Pottery in Northern Africa – An Overview". Journal of African Archaeology. 8 (2): 219–238. doi:10.3213/1612-1651-10171. ISSN 1612-1651.

- ^ Olivier P. Gosselain (2008). "Ceramics in Africa". Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. pp. 464–476. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4425-0_8911. ISBN 978-1-4020-4559-2.

- ^ "Archaeological Analysis", Ohio State Archeological excavations in Greece

- ^ "Palace Museum Opens Its New Porcelain Hall". chinaculture.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ "國立故宮全球資訊網-訊息頁". npm.gov.tw. Retrieved 19 March 2016.

- ^ Peterson 1996, p. 369.

- ^ "Le collezioni".

Sources

edit- Cooper, Emmanuel (2010). Ten Thousand Years of Pottery (4th ed.). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-3554-8. OCLC 42475956.

- Cooper, Emmanuel (1989). A History of World Pottery. Chilton Book Co. ISBN 978-0-8019-7982-8.

- Howard, Coutts (2001). The Art of Ceramics: European Ceramic Design 1500–1830. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08387-3.* Cox, Warren (1970). The book of pottery and porcelain. Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-517-53931-6.

- Dinsdale, Allen (1986). Pottery Science. Ellis Horwood, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-470-20276-0.

- Dodd, Arthur (1994). Dictionary of Ceramics: Pottery, Glass, Vitreous Enamels, Refractories, Clay Building Materials, Cement and Concrete, Electroceramics, Special Ceramics. Maney Publishing. ISBN 978-0-901716-56-9.

- Levin, Elaine (1988). The History of American Ceramics: From Pipkins and Bean Pots to Contemporary Forms, 1607 to the present. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-1172-7.

- Perry, Barbara (1989). American Ceramics: The Collection of Everson Museum of Art. Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-1025-3.

- Peterson, Susan (1996). The craft and art of clay. Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press. ISBN 978-0-87951-634-5. OCLC 604392596 – via Internet Archive.

- George, Savage; Newman, Harold (2000). Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27380-7.

External links

edit- Ceramic from the Victoria & Albert Museum

- Ceramic history for potters by Victor Bryant

- Index to the Metropolitan Museum Timeline of Art History – see "ceramics" for many features

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts: Ceramics – The Art of Asia* Potweb Online catalogue & more from the Ashmolean Museum

- Stoke-on-Trent Museums – Ceramics Online

- Royal Dutch Ceramics

- UK Ceramics Information – British Ceramic Brands

- The ceramic art of Great Britain (1878), Llewellynn Jewitt