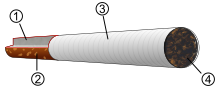

A cigarette filter, also known as a filter tip, is a component of a cigarette, along with cigarette paper, capsules and adhesives. Filters were introduced in the early 1950s.[3]

- Cigarette filter

- Imitation cork tip paper

- Cigarette paper

- Tobacco

Filters may be made from plastic cellulose acetate fiber, paper or activated charcoal (either as a cavity filter or embedded into the plastic cellulose acetate fibers). Macroporous phenol-formaldehyde resins and asbestos have also been used.[4][5] The plastic cellulose acetate filter and paper modify the particulate smoke phase by particle retention (filtration), and finely divided carbon modifies the gaseous phase (adsorption).[6]

Filters are intended to reduce the harm caused by smoking by reducing harmful chemicals inhaled by smokers. While laboratory tests show a reduction of "tar" and nicotine in cigarette smoke, filters are ineffective at removing gases of low molecular weight, such as carbon monoxide.[7] Most of these measured reductions[which?] occur only when the cigarette is smoked on a smoking machine; when smoked by a human, the compounds are delivered into the lungs regardless of whether a filter is used.[2]

Most factory-made cigarettes are equipped with a filter; those who roll their own can buy them from a tobacconist.[2]

History

editIn 1925, Hungarian inventor Boris Aivaz patented the process of making a cigarette filter from crepe paper.[8]

From 1935, Molins Machine Co Ltd [9] a British company began to develop a machine that made cigarettes incorporating the tipped filter. It was considered a specialty item until 1954, when manufacturers introduced the machine more broadly, following a spate of speculative announcements from doctors and researchers concerning a possible link between lung diseases and smoking. Since filtered cigarettes were considered safer, by the 1960s, they dominated the market. Production of filter cigarettes rose from 0.5 percent in 1950 to 87.7 percent by 1975.[10]

Between the 1930s and the 1950s, most cigarettes were 70 millimetres (2+3⁄4 in) long. The modern cigarette market includes mainly filter cigarettes that are 80, 85, 100, or 120 millimetres (3+1⁄8, 3+3⁄8, 3+7⁄8, or 4+3⁄4 in).[11]

Cigarettes filters were originally made of cork and used to prevent tobacco flakes from getting on the smoker's tongue. Many are still patterned to look like cork.[1]

Manufacture

editThe cigarette smoking public attaches great significance to visual examination of the filter material in filter tip cigarettes after smoking the cigarettes. A before and after smoking visual comparison is usually made and if the filter tip material, after smoking, is darkened, the tip is automatically judged to be effective. While the use of such colour change material would probably have little or no effect on the actual effectiveness of the filter tip material, the advertising and sales advantages are obvious.

— Claude Teague, the inventor of the colour-changing filter[2]

Cigarette filters are usually made from plastic cellulose acetate fibre,[3] but sometimes also from paper or activated charcoal (either as a cavity filter or embedded into the cellulose acetate).

Cellulose acetate is made by esterifying bleached cotton or wood pulp with acetic acid. Of the three cellulose hydroxy groups available for esterification, between two and three are esterified by controlling the amount of acid (degree of substitution (DS) 2.35-2.55). The ester is spun into fibers and formed into bundles called filter tow. Flavors (menthol), sweeteners, softeners (triacetin), flame retardants (sodium tungstate), breakable capsules releasing flavors on demand, and additives colouring the tobacco smoke[citation needed] may be added to cigarette filters.[12][13] The five largest manufactures of filter tow are Celanese and Eastman Chemicals in the United States, Cerdia in Germany, Daicel and Mitsubishi Rayon in Japan.

Starch glues or emulsion-based adhesives are used for gluing cigarette seams. Hot-melt and emulsion-based adhesives are used for filter seams. Emulsion-based adhesives are used for bonding the filters to the cigarettes.[14] The tip paper may be coated with polyvinyl alcohol.[15]

Colour change

editThe tobacco industry determined that the illusion of filtration was more important than filtration itself. The pH of the cellulose acetate used is modified, so that its colour becomes darker when exposed to smoke (this was invented in 1953 by Claude Teague,[1] working for R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company).[16] The industry wanted filters to be seen as effective for marketing reasons, despite not making cigarettes any less unhealthy.[3][failed verification]

Health risks

editThis article needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources, specifically: out-of-date sources, does not reflect the balance of evidence. (September 2018) |

In the 1970s epidemiologic evidence relative to tobacco-related cancers and data for coronary heart disease indicated a reduced risk among filter smokers for these diseases.[17] Between 1970 and 1980 some studies showed a 20-50% reduction in risk of lung cancer for long-term smokers of filtered cigarettes as compared to smokers of non-filtered cigarettes (IARC, 1986) but later studies indicated a similar risk for lung cancer in smokers of filtered and non-filtered cigarettes.[18] The risk reductions depend on different aspects such as the gender or whether a person is athletic, the study location, the age of the person, and when only studies providing both unadjusted and adjusted estimates were considered. Whether or not relative risk estimates are adjusted for cigarette consumption is not crucial to the conclusion of a clear advantage to filter cigarettes and tar reduction.[19]

Various add-on cigarette filters ("Water Pik", "Venturi", "David Ross") are sold as stop-smoking or tar-reduction devices. The idea is that filters reduce tar and nicotine levels, permitting the smoker to be weaned away from cigarettes.[20]

Light cigarettes

editThe tobacco industry has reduced tar and nicotine yields in cigarette smoke since the 1960s. This has been achieved in a variety of ways, including use of selected strains of tobacco plant, changes in agricultural and curing procedures, use of reconstituted sheets (reprocessed tobacco leaf waste), incorporation of tobacco stalks, reduction of the amount of tobacco needed to fill a cigarette by expanding it (like puffed wheat) to increase its "filling power", and by the use of filters and high-porosity wrapping papers. However, just as a drinker tends to drink a larger volume of beer than of wine or spirits, many smokers tend to inversely modify their smoking pattern according to the strength of the cigarette being smoked. In contrast to the standardized puffing of the smoking machines on which the tar and nicotine yields are based, when a smoker switches to a low-tar, low nicotine cigarette, they smoke more cigarettes, take more puffs and inhale more deeply. Conversely, when smoking a high-tar, high-nicotine cigarette there is a tendency to smoke and inhale less.[21]

In spite of the changes in cigarette design and manufacturing over the last fifty years, the use of filters and "light" cigarettes neither decreased the nicotine intake per cigarette, nor lowered the incidence of lung cancer (NCI, 2001; IARC 83, 2004; U.S. Surgeon General, 2004).[22] The shift over the years from higher- to lower-yield cigarettes may explain the change in the pathology of lung cancer. That is, the percentage of lung cancers that are adenocarcinomas has increased, while the percentage of squamous cell cancers has decreased. The change in tumor type is believed to reflect the higher nitrosamine delivery of lower-yield cigarettes and the increased depth or volume of inhalation of lower-yield cigarettes to compensate for lower level concentrations of nicotine in the smoke.[23]

Safety

editCellulose acetate is non-toxic, odorless, tasteless, and weakly flammable plastic. It is resistant to weak acids and is largely stable to mineral and fatty oils as well as petroleum. Smoked (i.e., used/discarded) cigarette butts contain 5–7 mg (~ 0.08-0.11 gr) of nicotine (about 25% of the total cigarette nicotine content). Cellulose acetate is hydrophilic and retains the water-soluble smoke constituents (many of which are irritating, including acids, alkali, aldehydes, and phenols), while letting through the lipophilic aromatic compounds.

Waste

editCigarette butts are the most littered anthropogenic (man-made) waste item in the world. Approximately 5.6 trillion cigarettes are smoked every year worldwide.[24] Of these, it is estimated that 4.5 trillion cigarette butts become litter every year.[25] The plastic cellulose acetate in cigarette butts biodegrades gradually, passing through the stage of microplastics.[26] The breakdown of discarded cigarette butts is highly dependent upon environmental conditions. A 2021 review article cites an experiment where 45-50% of cellulose acetate mass was fully degraded to CO2 after 55 days of controlled composting and another where negligible degradation took place after 12 weeks in pilot-scale compost.[27][28][29]

During the act of smoking, plastic cellulose acetate fibers and tipping paper absorb a wide range of chemicals that are present in tobacco smoke. After cigarette butts are discarded, they can leach toxins including nicotine, arsenic, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals into the environment.[30] Smoked cigarette butts and cigarette tobacco in butts have been shown to be toxic to water organisms such as the marine topsmelt (Atherinops affinis) and the freshwater fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas).[31]

Atmospheric moisture, gastric acid, light, and enzymes hydrolyze cellulose acetate to acetic acid and cellulose. Cellulose may be further hydrolyzed to cellobiose or glucose in an acidic medium. Humans cannot digest cellulose and excrete the fibers in feces, because, unlike ruminant animals, rabbits, rodents, termites, and some bacteria and fungi, they lack cellulolytic enzymes such as cellulase.[citation needed]

Many governments have sanctioned stiff penalties for littering of cigarette filters; for example Washington State imposes a penalty of $1,025 for littering cigarette filters.[32] Another option is developing better biodegradable filters. Much of this work relies heavily on the research about the secondary mechanism for photodegradation. However, making a product biodegradable means making it vulnerable to humidity and heat, which does not suit filters made for hot and humid smoke.[16] The next option is using cigarette packs with a compartment for discarded cigarette butts, implementing monetary deposits on filters, increasing the availability of cigarette receptacles, and expanding public education. Others have suggested banning the sale of filtered cigarettes altogether on the basis of their adverse environmental impact.[24]

Recent research has been put into finding ways to use the filter waste in order to develop other products. One research group in South Korea have developed a one-step process that converts the cellulose acetate in discarded cigarette filters into a high-performing supercapacitor electrode material. These materials have demonstrated superior performance as compared to commercially available carbon, graphene and carbon nano tubes.[33]

Another group of researchers has proposed adding tablets of food grade acid inside the filters. Once wet enough the tablets would release acid that accelerates degradation to around two weeks, instead of using cellulose triacetate and besides of cigarette smoke being quite acidic.[34]

Activated charcoal filtration

editCigarette filter can incorporate an activated charcoal filtration system. Instead of acetate or cardboard filters, it consists of two ceramic caps on either sides containing activated charcoal, which reduces tar and other toxins in the smoke.[35]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Kennedy, Pagan (8 July 2012). "Who Made That Cigarette Filter?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 14 March 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d Harris, Bradford (1 May 2011). "The intractable cigarette 'filter problem'". Tobacco Control. 20 (Suppl 1): –10–i16. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.040113. eISSN 1468-3318. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3088411. PMID 21504917.

- ^ a b c Monograph 13: Risks associated with smoking cigarettes with low tar machine-measured yields of tar and nicotine. National Cancer Institute (Report). United States Department of Health and Human Services. 2001.

- ^ Francois de Dardel; Thomas V. Arden (2007), "Ion Exchangers", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–74, doi:10.1002/14356007.a14_393, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Seymour S. Chissick (2007), "Asbestos", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–18, doi:10.1002/14356007.a03_151, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ T. C. Tso (2007), "Tobacco", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–26, doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_123, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Robert Kapp (2005), "Tobacco Smoke", Encyclopedia of Toxicology, vol. 4 (2nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 200–202, ISBN 978-0-12-745354-5

- ^ "The History of Filters". tobaccoasia.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2003. Retrieved 18 May 2008.

- ^ "Cigarette with Filter tip" (PDF).

- ^ Leonard M. Schuman (1977), "Patterns of Smoking Behavior", in Murray E. Jarvik; Joseph W. Cullen; Ellen R. Gritz; Thomas M. Vogt; Louis Jolyon West (eds.), Research on Smoking Behavior (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 17, pp. 36–65, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015, retrieved 21 October 2015

- ^ Lynn T. Kozlowski (1983), "Physical Indicators of Actual Tar and Nicotine Yields of Cigarettes", in John Grabowski; Catherine S. Bell (eds.), Measurement in the Analysis and Treatment of Smoking Behavior (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 48, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, pp. 50–61, PMID 6443144, archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2016, retrieved 29 March 2016

- ^ Ralf Christoph; Bernd Schmidt; Udo Steinberner; Wolfgang Dilla; Reetta Karinen (2007), "Glycerol", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–16, doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_477.pub2, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Erik Lassner; Wolf-Dieter Schubert; Eberhard Luderitz; Hans Uwe Wolf (2007), "Tungsten, Tungsten Alloys, and Tungsten Compounds", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–37, doi:10.1002/14356007.a27_229, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ Werner Haller; Hermann Onusseit; Gerhard Gierenz; Werner Gruber; Richard D. Rich; Günter Henke; Lothar Thiele; Horst Hoffmann; Dieter Dausmann; Riza-Nur Özelli; Udo Windhövel; Hans-Peter Sattler; Wolfgang Dierichs; Günter Tauber; Michael Hirthammer; Christoph Matz; Matthew Holloway; David Melody; Ernst-Ulrich Rust; Ansgar van Halteren (2007), "Adhesives", Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (7th ed.), Wiley, pp. 1–70, doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_221, ISBN 978-3527306732

- ^ F. L. Marten (2002), "Vinyl Alcohol Polymers", Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (5th ed.), Wiley, p. 26, doi:10.1002/0471238961.2209142513011820.a01.pub2, ISBN 0471238961

- ^ a b Robert N. Proctor (2012). Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520270169.

- ^ Ernst L. Wynder (1977), "Interrelationship of Smoking to Other Variables and Preventive Approaches", in Murray E. Jarvik; Joseph W. Cullen; Ellen R. Gritz; Thomas M. Vogt; Louis Jolyon West (eds.), Research on Smoking Behavior (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 17, pp. 67–95, PMID 417264, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015, retrieved 21 October 2015

- ^ K. Rothwell; et al. (1999), Health effects of interactions between tobacco use and exposure to other agents, Environmental Health Criteria, World Health Organization

- ^ Lee, Peter N.; Sanders, Edward (1 December 2004). "Does increased cigarette consumption nullify any reduction in lung cancer risk associated with low-tar filter cigarettes?". Inhalation Toxicology. 16 (13): 817–833. Bibcode:2004InhTx..16..817L. doi:10.1080/08958370490490185. ISSN 0895-8378. PMID 15513814. S2CID 22468291.

- ^ Jerome L. Schwartz (1977), "Smoking Cures: Ways to Kick an Unhealthy Habit", in Murray E. Jarvik; Joseph W. Cullen; Ellen R. Gritz; Thomas M. Vogt; Louis Jolyon West (eds.), Research on Smoking Behavior (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 17, pp. 308–336, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015, retrieved 21 October 2015

- ^ Michael A. H. Russell (1977), "Smoking Problems: An Overview", in Murray E. Jarvik; Joseph W. Cullen; Ellen R. Gritz; Thomas M. Vogt; Louis Jolyon West (eds.), Research on Smoking Behavior (PDF), NIDA Research Monograph, vol. 17, pp. 13–34, archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2015, retrieved 21 October 2015

- ^ Anthony J. Alberg; Jonathan M. Samet (2010), "Epidemiology of Lung Cancer", in Robert J. Mason; V. Courtney Broaddus; Thomas R. Martin; Talmadge E. King, Jr.; Dean E. Schraufnagel; John F. Murray; Jay A. Nadel (eds.), Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, vol. 1 (5th ed.), Saunders, ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0

- ^ Neal L. Benowitz; Paul G. Brunetta (2010), "Smoking Hazards and Cessation", in Robert J. Mason; V. Courtney Broaddus; Thomas R. Martin; Talmadge E. King, Jr.; Dean E. Schraufnagel; John F. Murray; Jay A. Nadel (eds.), Murray and Nadel's Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, vol. 1 (5th ed.), Saunders, ISBN 978-1-4160-4710-0

- ^ a b Novotny TE, Lum K, Smith E, et al. (2009). "Cigarettes butts and the case for an environmental policy on hazardous cigarette waste". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 6 (5): 1691–705. doi:10.3390/ijerph6051691. PMC 2697937. PMID 19543415.

- ^ "The world litters 4.5 trillion cigarette butts a year. Can we stop this?". The Houston Chronicle. 12 May 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Frederic Beaudry (3 July 2019). "Are Cigarette Butts Biodegradable?". treehugger.com. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Yadav, Nisha; Hakkarainen, Minna (2021). "Degradable or not? Cellulose acetate as a model for complicated interplay between structure, environment and degradation". Chemosphere. 265: 128731. Bibcode:2021Chmsp.26528731Y. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128731. PMID 33127118.

- ^ Cantú, Aaron (12 February 2014). "New 'Green' Cigarette Butts Biodegrade Within Days—And Can Even Sprout Into Grass - The company Greenbutts is manufacturing a new filter to address most common litter problem". AlterNet.

- ^ Chamas, Ali (2020). "Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment". ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 8 (9): 3494–3511. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06635.

- ^ Moriwaki, Hiroshi; Kitajima, Shiori; Katahira, Kenshi (2009). "Waste on the roadside, 'poi-sute' waste: Its distribution and elution potential of pollutants into environment". Waste Management. 29 (3): 1192–1197. Bibcode:2009WaMan..29.1192M. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2008.08.017. hdl:10091/3192. PMID 18851907.

- ^ Slaughter E, Gersberg RM, Watanabe K, Rudolph J, Stransky C, Novotny TE (2011). "Toxicity of cigarette butts, and their chemical components, to marine and freshwater fish". Tobacco Control. 20 (Suppl_1): 25–29. doi:10.1136/tc.2010.040170. PMC 3088407. PMID 21504921.

- ^ "Accidents, fires: Price of littering goes beyond fines". Washington: State of Washington Department of Ecology. 1 June 2004. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ Minzae L, Gil-Pyo K, Hyeon DS, Soomin P, Jongheop Y (2014). "Preparation of energy storage material derived from a used cigarette filter for a supercapacitor electrode". Nanotechnology. 25 (34): 34. Bibcode:2014Nanot..25H5601L. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/25/34/345601. PMID 25092115. S2CID 8692351.

- ^ "No more butts: biodegradable filters a step to boot litter problem". Environmental Health News. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- ^ Goel, R.; Bitzer, Z. T.; Reilly, S. M.; Bhangu, G.; Trushin, N.; Elias, R. J.; Foulds, J.; Muscat, J.; Richie Jr, J. P. (2018). "Effect of Charcoal in Cigarette Filters on Free Radicals in Mainstream Smoke". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 31 (8): 745–751. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrestox.8b00092. PMC 6471497. PMID 29979036.