The Ford Richmond Plant, formally the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant, in Richmond, California, was the largest assembly plant to be built on the West Coast[2] and its conversion to wartime production during World War II aided the United States' war effort. The plant is part of the Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It currently houses the National Park Service visitor center, several private businesses and the Craneway Pavilion, an event venue.

Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant | |

| |

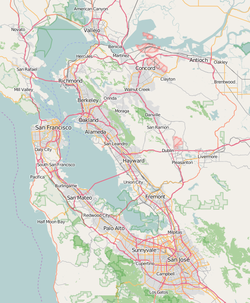

| Location | Richmond, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 37°54′38.6″N 122°21′30.1″W / 37.910722°N 122.358361°W |

| Built | 1930 |

| Architect | Albert Kahn |

| NRHP reference No. | 88000919 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 23, 1988 |

Construction

editBuilt in 1930 during the Great Depression, the assembly plant measures nearly 500,000 square feet (46,450 m2). The factory was a major stimulant to the local and regional economy and was an important development in Richmond's inner harbor and port plan.[2] Ford became Richmond's third largest employer, behind Standard Oil and the Santa Fe Railroad. It is also an outstanding example of 20th-century industrial architecture designed by architect Albert Kahn, known for his "daylight factory" design, which employed extensive window openings that became his trademark. The main building is composed of a two-story section, a single-story section, a craneway, a boiler house and a shed canopy structure over the railroad track.

World War II

editTo ensure that America prepared for total war by mobilizing all the industrial might of the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt banned the production of civilian automobiles during World War II. The Richmond Ford Assembly Plant switched to assembling jeeps and to putting the finishing touches on tanks, half-tracked armored personnel carriers, armored cars and other military vehicles destined for the Pacific Theater. By July 1942, military combat vehicles began flowing into the Richmond Ford plant to get final processing before being transported out the deep-water channel to the war zones. The "Richmond Tank Depot" (only one of three tank depots in the country[3]) as the Ford plant was then called, helped keep American fighting men supplied with up-to-the-minute improvements in their battle equipment. Approximately 49,000 jeeps were assembled and 91,000 other military vehicles were processed here.[3]

In mobilizing the wartime production effort to its full potential, Federal military authorities and private industry began to work closely together on a scale never seen before in American history. This laid the groundwork for what became known as the "military-industrial complex" during the Cold War years.[2] This Assembly Plant was one cog in the mobilization of the "Arsenal of Democracy" and a historic part of what is today's industrial culture of the United States.

Post-war

editAfter the war, the devastation to the local economy as a result of the closing of the Richmond Shipyards would have been crippling had it not been for the continued production of the Ford Plant. The last Ford was assembled in February 1953, with the plant being closed in 1956 and production transferred to the San Jose Assembly Plant because of the inability to accommodate increased productivity demands.

The plant was featured in the movie Tucker: The Man and His Dream. Principal photography started with first unit shooting on April 13, 1987 in the Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant in Richmond, California.

In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake severely damaged the plant. After the earthquake, the City of Richmond repaired and prepared the Ford Assembly building for rehabilitation and selected Orton Development as the developer of the rehabilitation project. In 2008, after the building's rehabilitation was completed, tenants including SunPower Corporation and Mountain Hardwear made the building their new home. The craneway ("Craneway Pavilion")[4] of the building is also used for banquets, weddings, and corporate events.[5][6] In 2018, the Craneway Conference Center was the venue for West Edge Opera's summer opera festival.[7] In April 2020, Contra Costa County officials announced that the Craneway Pavilion would be converted into a 250-bed hospital for COVID-19 patients who do not require an intensive care unit level of care, which has since closed. The California National Guard helped set up the facility.[8] Currently, the Craneway Pavilion is used for a privately run pickleball and ping-pong hall, open to paying customers.[9]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 15, 2006.

- ^ a b c "Ford Motor Company Assembly Plant". World War II in the San Francisco Bay Area. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ a b "Self-Guided Auto Tour" (PDF). Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park. National Park Service. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ^ Craneway Pavilion: Venue - About

- ^ Skrillex Insomniac Halloween Archived copy

- ^ Björk Breathes New Life Into Craneway Pavilion - East Bay Express

- ^ Rowe, Georgia (30 July 2018). "Why SF Bay Area's West Edge company does opera like no one else". San Jose Mercury News. Bay Area News Group. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ Lee, Henry; Fernandez, Lisa (April 2, 2020). "The Craneway Pavilion in Richmond used in WWII to be converted into a federal medical station for COVID-19 patients". KTVU. Oakland, California. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Pickleball". Craneway Pavilion. Retrieved 2024-10-31.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the National Park Service.