Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is a class of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, which is a type of cancer of the immune system. Unlike most non-Hodgkin lymphomas (which are generally B-cell-related), CTCL is caused by a mutation of T cells. The cancerous T cells in the body initially migrate to the skin, causing various lesions to appear. These lesions change shape as the disease progresses, typically beginning as what appears to be a rash which can be very itchy and eventually forming plaques and tumors before spreading to other parts of the body.

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma | |

|---|---|

| |

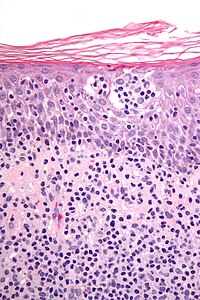

| Micrograph showing cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. H&E stain | |

| Specialty | Hematology and oncology |

Signs and symptoms

editThe presentation depends if it is mycosis fungoides or Sézary syndrome, the most common, though not the only types. Among the symptoms for the aforementioned types are: enlarged lymph nodes, an enlarged liver and spleen, and non-specific dermatitis.[1]

Cause

editThe cause of CTCL remains largely unknown, but several external risk factors have been proposed as potential triggers and promoters of the disease. These include the use of hydrochlorothiazide diuretics, therapy-induced immunosuppression, and possible infections by a range of viral (e.g., HTLV-1, HTLV-2, HIV, Epstein-Barr virus, Cytomegalovirus, HHV-6, HHV-7, HHV-8 (KSHV), and Polyomaviruses such as Merkel cell polyomavirus) and bacterial or fungal pathogens (including Staphylococcus aureus, Mycobacterium leprae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and dermatophytes). The level of evidence varies among the different factors.[2]

Diagnosis

editA point-based algorithm for the diagnosis for early forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma was proposed by the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas in 2005.[3]

Classification

editCutaneous T-cell lymphoma may be divided into the several subtypes.[4]: 727–740 Mycosis fungoides is the most common form of CTCL and is responsible for half of all cases.[5] A WHO-EORTC classification has been developed.[6][7][8][9]

- Pagetoid reticulosis

- Sézary syndrome

- Granulomatous slack skin

- Lymphomatoid papulosis

- Pityriasis lichenoides chronica

- Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta

- CD30+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Secondary cutaneous CD30+ large cell lymphoma

- Non-mycosis fungoides CD30− cutaneous large T-cell lymphoma

- Pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma

- Lennert lymphoma

- Subcutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Angiocentric lymphoma

- Blastic NK-cell lymphoma

- Primary cutaneous anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

- Primary cutaneous acral CD8 positive T cell lymphoproliferative disorder

Treatment

editThere is no cure for CTCL, but there are a variety of treatment options available and some CTCL patients are able to live normal lives with this cancer, although symptoms can be debilitating and painful, even in earlier stages. FDA approved treatments include the following:[10]

- (1999) Denileukin diftitox (Ontak)

- (2000) Bexarotene (Targretin) a retinoid

- (2006) Vorinostat (Zolinza) a hydroxymate histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor

- (2009) Romidepsin (Istodax) a cyclic peptide histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor

- (2018) Poteligeo (mogamulizumab-kpkc)

Histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors are shown to have antiproliferative and cytotoxic properties against CTCL.[11] Other (off label) treatments include:

- Topical and oral corticosteroids

- Bexarotene (Targretin) gel and capsules

- Carmustine (BCNU, a nitrosourea)

- Mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard)

- Phototherapy (broad and narrow band UVB or PUVA)

- Electron therapy

- Conventional radiation therapy

- Photopheresis

- Interferons

- Alemtuzumab (Campath-1H)

- Methotrexate

- Pentostatin and other purine analogues (Fludarabine, 2-deoxychloroadenosine)

- Liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil)

- Gemcitabine (Gemzar)

- Cyclophosphamide

- Bone marrow / stem cells

- Allogenic transplantation

- Forodesine (inhibits purine nucleoside phosphorylase)

In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted orphan drug designation for naloxone lotion as a treatment for pruritus in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma to a pharmaceutical company called Elorac.[12]

Epidemiology

editOf all cancers involving lymphocytes, 2% of cases are cutaneous T cell lymphomas.[13] CTCL is more common in men and in African-American people.[10] The incidence of CTCL in men is 1.6 times higher than in women.[10]

There is some evidence of a relationship with human T-lymphotropic virus (HTLV) with the adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma subtype.[10] No definitive link between any viral infection or environmental factor has been definitely shown with other CTCL subtypes.[10]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 2016-06-02.

- ^ Ghazawi, Feras M.; Alghazawi, Nebras; Le, Michelle; Netchiporouk, Elena; Glassman, Steven J.; Sasseville, Denis; Litvinov, Ivan V. (2019). "Environmental and Other Extrinsic Risk Factors Contributing to the Pathogenesis of Cutaneous T Cell Lymphoma (CTCL)". Frontiers in Oncology. 9: 300. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00300. ISSN 2234-943X. PMC 6499168. PMID 31106143.

- ^ Pimpinelli, Nicola; Olsen, Elise A.; Santucci, Marco; Vonderheid, Eric; Haeffner, Andreas C.; Stevens, Seth; Burg, Guenter; Cerroni, Lorenzo; Dreno, Brigitte (December 2005). "Defining early mycosis fungoides" (PDF). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 53 (6): 1053–1063. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.08.057. hdl:2158/311708. PMID 16310068.

- ^ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- ^ Sidiropoulos, KG; Martinez-Escala, ME; Yelamos, O; Guitart, J; Sidiropoulos, M (December 2015). "Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas: a review". Journal of Clinical Pathology (Review). 68 (12): 1003–10. doi:10.1136/jclinpath-2015-203133. PMID 26602417. S2CID 44407772.

- ^ Willemze, R.; Jaffe, ES.; Burg, G.; Cerroni, L.; Berti, E.; Swerdlow, SH.; Ralfkiaer, E.; Chimenti, S.; et al. (May 2005). "WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas". Blood. 105 (10): 3768–85. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. hdl:2434/566817. PMID 15692063.

- ^ Khamaysi, Z.; Ben-Arieh, Y.; Izhak, OB.; Epelbaum, R.; Dann, EJ.; Bergman, R. (Feb 2008). "The applicability of the new WHO-EORTC classification of primary cutaneous lymphomas to a single referral center". Am J Dermatopathol. 30 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815f9841. PMID 18212543. S2CID 13571836.

- ^ Melchers RC, Willemze R, van de Loo M, van Doorn R, Jansen PM, Cleven AH, Solleveld N, Bekkenk MW, van Kester MS, Diercks GF, Vermeer MH, Quint KD (June 2020). "Clinical, Histologic, and Molecular Characteristics of Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase-positive Primary Cutaneous Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 44 (6): 776–781. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001449. hdl:1887/3280088. PMID 32412717. S2CID 213450901.

- ^ Saleh JS, Subtil A, Hristov AC (August 2023). "Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: a review of the most common entities with focus on recent updates". Human Pathology. 138: 76–102. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2023.06.001. PMID 37307932.

- ^ a b c d e Devata, S; Wilcox, RA (June 2016). "Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: A Review with a Focus on Targeted Agents". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology (Review). 17 (3): 225–37. doi:10.1007/s40257-016-0177-5. PMID 26923912. S2CID 28520647.

- ^ Beigi, Pooya Khan Mohammad (2017). "Treatment". Clinician's Guide to Mycosis Fungoides. Springer International Publishing. pp. 23–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-47907-1_6. ISBN 9783319479064.

- ^ Elorac, Inc. Announces Orphan Drug Designation for Novel Topical Treatment for Pruritus in Cutaneous T-cell Lymphoma (CTCL) Archived 2010-12-30 at the Wayback Machine website

- ^ Turgeon, Mary Louise (2005). Clinical hematology: theory and procedures. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-7817-5007-3.

Frequency of lymphoid neoplasms. (Source: Modified from WHO Blue Book on Tumour of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. 2001, p. 2001.)

External links

edit