The European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II) is a system introduced by the European Economic Community on 1 January 1999 alongside the introduction of a single currency, the euro (replacing ERM 1 and the euro's predecessor, the ECU) as part of the European Monetary System (EMS), to reduce exchange rate variability and achieve monetary stability in Europe.

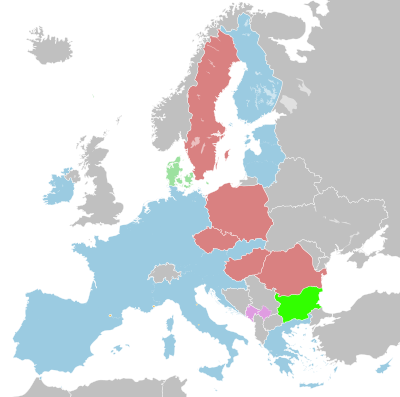

After the adoption of the euro, policy changed to linking currencies of EU countries outside the eurozone to the euro (having the common currency as a central point). The goal was to improve the stability of those currencies, as well as to gain an evaluation mechanism for potential eurozone members. As of March 2024, two currencies participate in ERM II: the Danish krone and the Bulgarian lev.

Intent and operation of the ERM II

editThe ERM is based on the concept of fixed currency exchange rate margins, but with exchange rates variable within those margins. This is also known as a semi-pegged system. Before the introduction of the euro, exchange rates were based on the European Currency Unit (ECU), the European unit of account, whose value was determined as a weighted average of the participating currencies.[1]

A grid (known as the Parity Grid) of bilateral rates was calculated on the basis of these central rates expressed in ECUs, and currency fluctuations had to be contained within a margin of 2.25% on either side of the bilateral rates (with the exception of the Italian lira, the Spanish peseta, the Portuguese escudo and Pound sterling, which were allowed to fluctuate by ±6%).[2] Determined intervention and loan arrangements protected the participating currencies from greater exchange rate fluctuations.

United Kingdom Chancellor of the Exchequer Denis Healey reportedly chose not to join the ERM in 1979 owing to concerns that it would benefit the German economy by preventing the Deutsche Mark from appreciating, at the expense of the economies of other countries.[3] The UK did join the ERM in October 1990 under Chancellor John Major, in a move which at the time was largely supported by business and the press,[4] but was forced to leave again two years later on Black Wednesday.[5]

Historical exchange-rate regimes for EU members

editThe chart below provides a full summary of all applying exchange-rate regimes for EU members, since the European Monetary System with its Exchange Rate Mechanism and the related new common currency ECU came into being on 13 March 1979. The euro replaced the ECU 1:1 at the exchange rate markets, on 1 January 1999. Between 1979 and 1999 the D-Mark functioned as a de facto anchor for the ECU, meaning there was only a minor difference between pegging a currency against the ECU and pegging it against the D-Mark.

Sources: EC convergence reports 1996-2014, Italian lira, Spanish peseta, Portuguese escudo, Finnish markka, Greek drachma, Sterling

The eurozone was established with its first 11 member states on 1 January 1999. The first enlargement of the eurozone, to Greece, took place on 1 January 2001, one year before the euro had physically entered into circulation. The zone's next enlargements were with states that joined the EU in 2004, and then joined the eurozone on 1 January in the mentioned year: Slovenia (2007), Cyprus (2008), Malta (2008), Slovakia (2009), Estonia (2011), Latvia (2014), Lithuania (2015). Croatia, which joined in the EU 2013, adopted the euro in 2023.

All new EU members having joined the bloc after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992 are obliged to adopt the euro under the terms of their accession treaties.[6] However, the last of the five economic convergence criteria, which need to be complied with in order to qualify for euro adoption, is the exchange rate stability criterion. This requires having been a member of the ERM for a minimum of two years without the presence of "severe tensions" for the currency exchange rate.[7]

Irish pound breaks parity with sterling

editTo participate in the European Monetary System, Ireland chose to break the Irish pound's parity with sterling in 1979, because the UK had decided not to participate.[8] (The Irish Central Bank had maintained parity with sterling since the foundation of the state in 1922. "It was only in the 1970s, when high inflation in the UK threatened price stability in Ireland, that alternatives were seriously considered".[8])

Sterling's forced withdrawal from the ERM

editThe United Kingdom entered the ERM in October 1990, but was forced to exit the programme within two years after sterling came under major pressure from currency speculators. The ensuing crash of 16 September 1992 was subsequently dubbed "Black Wednesday". There was some revision of attitude towards this event given the UK's strong economic performance after 1992, with some commentators dubbing it "White Wednesday".[9]

Some commentators, following Norman Tebbit, took to referring to ERM as an "Eternal Recession Mechanism",[10] after the UK fell into recession in 1990. The UK spent over £6 billion trying to keep the currency within the narrow limits with reports at the time widely noting that the controversial Hungarian-American investor George Soros's individual profit of £1 billion equated to over £12 for each man, woman and child in Britain and dubbing Soros "the man who broke the Bank of England".[11][12][13]

Britain's membership of the ERM was also blamed for prolonging the recession at the time,[14] and Britain's exit from the ERM was seen as an economic failure which contributed significantly to the defeat of the Conservative government of John Major at the general election in May 1997, despite the strong economic recovery and significant fall in unemployment which that government had overseen after Black Wednesday.[15]

Increase of margins

editIn August 1993, the margin was expanded to 15% to accommodate speculation against the French franc and other currencies.[16]

History of the ERM II

editOn 31 December 1998, the European Currency Unit (ECU)[17] exchange rates of the eurozone countries were frozen and the value of the euro, which then superseded the ECU at par, was thus established.

In 1999, ERM II replaced the original ERM.[18][page needed] The Greek and Danish currencies were part of the new mechanism, but when Greece joined the euro in 2001, the Danish krone was left at that time as the only participant member. A currency in ERM II is allowed to float within a range of ±15% with respect to a central rate against the euro. In the case of the krone, Danmarks Nationalbank keeps the exchange rate within the narrower range of ± 2.25% against the central rate of EUR 1 = DKK 7.46038.[19][20]

EU countries that have not adopted the euro are expected to participate for at least two years in ERM II before joining the eurozone.[6][7]

New EU members

editOn 1 May 2004, the ten national central banks (NCBs) of the new member countries became party to the ERM II Central Bank Agreement. The national currencies themselves were to become part of the ERM II at dates to be agreed.[21]

The Estonian kroon, Lithuanian litas, and Slovenian tolar were included in the ERM II on 28 June 2004; the Cypriot pound, the Latvian lats and the Maltese lira on 2 May 2005; the Slovak koruna on 28 November 2005.[22]

On 10 July 2020 it was announced that the Bulgarian lev (which had joined the EU on 1 January 2007) and Croatian kuna (which had joined the EU on 1 July 2013) would be included in the ERM II.[23][24]

These states (with the exception of Bulgaria) have all since joined the eurozone, and hence left ERM II: Slovenia (1 January 2007), Cyprus (1 January 2008), Malta (1 January 2008), Slovakia (1 January 2009), Estonia (1 January 2011), Latvia (1 January 2014), Lithuania (1 January 2015),[25] and Croatia (1 January 2023).[26]

Current status

editAs of January 2023, two currencies participate in ERM II: the Danish krone and the Bulgarian lev. The currencies of Sweden (the Swedish krona), the three largest countries which joined the European Union on 1 May 2004 (the Polish złoty, the Czech koruna, and the Hungarian forint), and Romania which joined on 1 January 2007 (the Romanian leu), are required to join in accordance with the terms of the applicable treaties of accession.

Sweden has voted in a referendum to stay out of the mechanism, despite being expected to join by the ECB, since Sweden has no opt-out like Denmark. EU members are required to join the ERM by the Maastricht convergence criteria.[27]

Exchange rate bands

editIn theory, most of the currencies are allowed to fluctuate as much as 15% from their assigned value.[16] In practice, however, the currency of Denmark deviates very little.[28]

| Date of entry [20][29] | Country | Currency | €1 =[20] | Band | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Actual | |||||

| 1 January 1999 | Denmark | Krone (kr.) | 7.46038 | 2.25% | <1% | The krone entered the ERM II in 1999, when the euro was created. See Denmark and the euro for more information. |

| 10 July 2020 | Bulgaria | Lev (лв.) | 1.95583 | 15% | 0% | The lev has been on the currency board since 1997 through a fixed exchange rate of the Bulgarian lev against the Deutsche Mark. See Bulgaria and the euro for more information. The euro is targeted to be introduced on January 1, 2025, making the euro the country's second currency after more than 140 years of the lev being the national currency. |

Historical reference

editThe former members of ERM II are the Greek drachma, Slovenian tolar, Cypriot pound, Estonian kroon, Maltese lira, Slovak koruna, Latvian lats, Lithuanian litas, and Croatian kuna.[25]

| Period | Country | Currency | €1.00 = | Band | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal | Actual | |||||

| 1 January 1999 – 16 January 2000 |

Greece | Drachma (₯) | 353.109[30] | 15% | Unknown | |

| 17 January 2000 – 31 December 2000 |

340.75[31] | Unknown | ||||

| 28 June 2004 – 31 December 2006 |

Slovenia | Tolar (T) | 239.64[32] | 15% | 0.16%[33] | |

| 2 May 2005 – 7 December 2007 |

Cyprus | Pound (£C) | 0.585274 | 15% | 2.1%[33] | |

| 7 December 2007 – 31 December 2007 |

0% | |||||

| 2 May 2005 – 31 December 2007 |

Malta | Lira (Lm) | 0.4293 | 15% | 0% | The lira had been pegged to the euro since joining ERM II. Only two exceptions exist: 2005-05-02 (ECB rate: 1 EUR = 0.4288 MTL) and 2005-08-15 (ECB rate: 1 EUR = 0.4292 MTL).[33] |

| 28 November 2005 – 16 March 2007 |

Slovakia | Koruna (Sk.) | 38.455[34][35][36] | 15% | 12%[33] | |

| 17 March 2007 – 27 May 2008 |

35.4424[37][38] | 12%[33] | ||||

| 28 May 2008 – 31 December 2008 |

30.126[39] | 1.9%[33] | ||||

| 28 June 2004 – 31 December 2010 |

Estonia | Kroon (kr.) | 15.6466 | 15% | 0% | The kroon had been pegged to the D–Mark since its re-introduction on 20 June 1992, and then to the euro. |

| 2 May 2005 – 31 December 2013 |

Latvia | Lats (Ls.) | 0.702804 | 15% | 1% | Latvia had a fixed exchange-rate system arrangement whose anchor switched from the SDR to the euro on 1 January 2005. |

| 28 June 2004 – 31 December 2014 |

Lithuania | Litas (Lt.) | 3.4528 | 15% | 0% | The litas was pegged to the US dollar until 2 February 2002, when it switched to a euro peg. |

| 10 July 2020 – 31 December 2022 |

Croatia | Kuna (kn.) | 7.53450 | 15% | 0% | |

See also

editCitations

edit- ^ "European Currency Unit Definition from Financial Times Lexicon". lexicon.ft.com. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "Economic and Monetary Union". European Commission – European Commission.

- ^ William Keegan: David Cameron's EU referendum raises spectre of Thatcher-era euroscepticism W. Keegan, International Business Times, 19 October 2015

- ^ John Major (1999). John Major: The Autobiography. Harper Collins. p. 163.

- ^ Eichengreen, Barry; Naef, Alain (2022). "Imported or Home Grown? The 1992-3 EMS Crisis". Journal of International Economics. Cambridge, MA. doi:10.3386/w29488.

- ^ a b "The problem with Europe is the euro". The Guardian. 10 August 2016. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Radio Prague – Czech officials talk up euro adoption but target date still not on agenda". Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ a b Irish Central Bank (Spring 2003). "The Irish Pound: From Origins to EMU" (PDF). Quarterly Bulletin. IE. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ Kaletsky, Anatole (9 June 2005). "The reason that Europe is having a breakdown...it's the Euro, stupid". The Times. UK. Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Tebbit, Norman (10 February 2005). "An electoral curse yet to be lifted". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 30 December 2008.

- ^ Slater, Robert (1996). Soros : the life, times & trading secrets of the world's greatest investor. Burr Ridge, Ill.: Irwin Professional Pub. p. 186. ISBN 0786303611.

- ^ Constable, Nick (2003). This is gambling. London: Sanctuary. pp. 46, 168. ISBN 1860744958.

- ^ Slater, Robert (2009). Soros the world's most influential investor. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0071608459.

- ^ Davis, Evan (15 September 2002). "Lessons learned on 'Black Wednesday'". BBC News.

- ^ "1997: Labour landslide ends Tory rule". BBC News. 15 April 2005.

- ^ a b Sirtaine, Sophie; Skamnelos, Ilias (1 January 2007). Credit Growth in Emerging Europe: A Cause for Stability Concerns?. World Bank Publications. p. 30.

- ^ "Council Regulation (EC) No 1103/97 of 17 June 1997 on certain provisions relating to the introduction of the euro". Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ^ Bitzenis, Aristidis (23 March 2016). The Balkans: Foreign Direct Investment and EU Accession. Routledge. ISBN 9781317040651.

- ^ "Learn about inflation, interest rates and the fixed exchange rate policy". Danmarks Nationalbank. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c "Foreign exchange operations". European Central Bank. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "What is ERM II? – European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "European Central Bank". European Central Bank. 28 November 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ European Central Bank (10 July 2020). "Communiqué on Bulgaria" (Press release) – via www.ecb.europa.eu.

- ^ European Central Bank (10 July 2020). "Communiqué on Croatia" (Press release) – via www.ecb.europa.eu.

- ^ a b "A timeline of the eurozone's growth". POLITICO. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "Croatia set to join the euro area on 1 January 2023: Council adopts final required legal acts". www.consilium.europa.eu. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Sweden 'not ready' for euro". BBC News. 22 May 2002. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- ^ Ryan (19 May 2016). "Danish Central Bank Stumbles with Its Currency Peg to the Euro". Mises Institute. Retrieved 31 December 2016.

- ^ "ERM II – the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism". European Commission.

- ^ "31 December 1998 – Euro central rates and intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 31 December 1998. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "17 January 2000 – Euro central rates and intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 17 January 2000. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "28 June 2004 – Euro central rates and compulsory intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 28 June 2004. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "ECB historic exchange rates". Ecb.eu. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "28 November 2005 – Euro central rates and compulsory intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 28 November 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Slovak Koruna Included in the ERM II". National Bank of Slovakia. 28 November 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ European Commission. "Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II)". Archived from the original on 23 April 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ Radoslav Tomek and Meera Louis (17 March 2007). "Slovakia, EU Raise Koruna's Central Rate After Appreciation". Bloomberg. Retrieved 17 March 2007.

- ^ "Euro central rates and compulsory intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 19 March 2007. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- ^ "Euro central rates and compulsory intervention rates in ERM II". European Central Bank. 29 May 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2011.