Escitalopram, sold under the brand names Lexapro and Cipralex, among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.[9] Escitalopram is mainly used to treat major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder.[9] It is taken by mouth,[9] available commercially as an oxalate salt exclusively.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌɛsəˈtæləˌpræm/ |

| Trade names | Cipralex, Lexapro, others[1] |

| Other names | (S)-Citalopram; S-Citalopram; S-(+)-Citalopram; S(+)-Citalopram; (+)-Citalopram; LU-26054; MLD-55 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a603005 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~80%[7][8] |

| Protein binding | ~55–56% (low)[7][8] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C19, CYP3A4, CYP2D6)[7][8] |

| Metabolites | • Desmethylcitalopram[7][8] • Didesmethylcitalopram[7][8] |

| Elimination half-life | ~27–32 hours[7] |

| Excretion | Urine (major; 8–10% unchanged), feces (minor)[8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.244.188 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

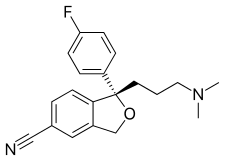

| Formula | C20H21FN2O |

| Molar mass | 324.399 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Levorotatory enantiomer |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include trouble sleeping, nausea, sexual problems, and feeling tired.[9] More serious side effects may include suicidal thoughts in people up to the age of 24 years.[9] It is unclear if use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is safe.[10] Escitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer of citalopram (which exists as a racemate), hence the name es-citalopram.[9]

Escitalopram was approved for medical use in the United States in 2002.[9] Escitalopram is rarely replaced by twice the dose of citalopram; escitalopram is safer and more effective.[11] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12] In 2022, it was the fifteenth most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 30 million prescriptions.[13][14] In Australia, it was one of the top 10 most prescribed medications between 2017 and 2023.[15]

Medical uses

editEscitalopram is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and adults, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in adults.[9] In European countries including the United Kingdom, it is approved for depression and anxiety disorders; these include: generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (SAD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), and panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. In Australia it is approved for major depressive disorder.[16][17][18]

Depression

editEscitalopram is among the most effective and well-tolerated antidepressants for the short-term treatment of major depressive disorder in adults.[19][20] It is also the safest one to give to children and adolescents.[21][22]

Controversy existed regarding the effectiveness of escitalopram compared with its predecessor, citalopram. The importance of this issue followed from the greater cost of escitalopram relative to the generic mixture of isomers of citalopram, prior to the expiration of the escitalopram patent in 2012, which led to charges of evergreening. Accordingly, this issue has been examined in at least 10 different systematic reviews and meta analyses. As of 2012[update], reviews had concluded (with caveats in some cases) that escitalopram is modestly superior to citalopram in efficacy and tolerability.[23][24][25][26]

Anxiety disorders

editEscitalopram appears to be effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder, with relapse on escitalopram at 20% rather than placebo at 50%, which translates to a number needed to treat of 3.33.[27][28] Escitalopram appears effective in treating social anxiety disorder as well.[29]

Other

editEscitalopram is effective in reducing the symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS), whether taken continuously or in the luteal phase only.[30][needs update]

Side effects

editEscitalopram, like other SSRIs, has been shown to affect sexual function, causing side effects such as decreased libido, delayed ejaculation, and anorgasmia.[31][32]

There is also evidence that SSRIs may cause an increase in suicidal ideation. An analysis conducted by the FDA found a statistically insignificant 1.5 to 2.4-fold (depending on the statistical technique used) increase of suicidality among the adults treated with escitalopram for psychiatric indications.[33][34][35] The authors of a related study note the general problem with statistical approaches: due to the rarity of suicidal events in clinical trials, it is hard to draw firm conclusions with a sample smaller than two million patients.[36]

Citalopram and escitalopram are associated with a mild dose-dependent QT interval prolongation,[37] which is a measure of how rapidly the heart muscle repolarizes after each heartbeat. Prolongation of the QT interval is a risk factor for torsades de pointes (TdP), a heart rhythm disturbance that is sometimes fatal. Despite the observed change in the QT interval, the risk of TdP from escitalopram appears to be quite low, and it is similar to other antidepressants that are not known to affect QT interval. A 2013 review[38] discusses several reasons to be optimistic about the safety of escitalopram. It references a crossover study in which 113 subjects were each given four different treatments in randomized order: placebo, 10 mg/day escitalopram, 30 mg/day escitalopram, or 400 mg/day moxifloxacin (a positive control known to cause QTc prolongation). At 10 mg/day, escitalopram increased the QTc interval by 4.5 milliseconds (ms). At 30 mg/day, the QTc increased by 10.7 ms.[39] A QTc increase of less than 60 ms is not likely to confer significant risk.[38] The 30 mg/day escitalopram dose induced significantly less QTc prolongation than a therapeutically equivalent 60 mg/day dose of citalopram, which increased the QTc interval by 18.5 ms.[38]

More data about the cardiac risk from escitalopram can be found in a large observational study from Sweden that took note of all the medications used by all the patients presenting with TdP, and found the incidence of TdP in escitalopram users to be only 0.7 cases of TdP for every 100,000 patients who took the drug (ages 18-64), and only 4.1 cases of TdP for every 100,000 elderly patients who took the drug (ages 65 and up).[40] Of the 9 antidepressants that were used by patients with TdP, escitalopram ranked 7th by TdP incidence in elderly patients (only venlafaxine and amitriptyline had less risk), and it ranked 5th of 9 by TdP incidence in patients ages 18-64. Antidepressants as a class had a relatively low risk of TdP, and most patients on an antidepressant who experienced TdP were also taking another drug that prolongs QT interval. Specifically, 80% of the escitalopram users who experienced TdP were taking at least one other drug known to cause TdP. For comparison, the most popular antiarrhythmic drug in the study was sotalol with 52,750 users, and sotalol had a TdP incidence of 81.1 cases and 41.2 cases of TdP per 100,000 users in the ≥65 and 18-64 year-old demographics, respectively.[40]

Drugs that prolong the QT interval, such as escitalopram, should be used with caution in those with congenital long QT syndrome or known pre-existing QT interval prolongation, or in combination with other medicines that prolong the QT interval. ECG measurements should be considered for patients with cardiac disease, and electrolyte disturbances should be corrected before starting treatment. In December 2011, the UK implemented new restrictions on the maximum daily doses at 20 mg for adults and 10 mg for those older than 65 years or with liver impairment.[41][42] The US Food and Drug Administration and Health Canada did not similarly order restrictions on escitalopram dosage, only on its predecessor citalopram.[43]

Like other SSRIs, escitalopram has also been reported to cause hyponatremia (low sodium levels), with rates ranging from 0.5 to 32%, which can often be attributed to SIADH.[44] This is typically not dose dependent and at higher risk for occurrence within the first few weeks of starting treatment.[45]

Very common effects

editVery common effects (>10% incidence) include:[46][47][48][5][49]

- Headache (24%)

- Nausea (18%)

- Ejaculation disorder (9–14%)

- Somnolence (4–13%)

- Insomnia (7–12%)

Common (1–10% incidence)

editCommon effects (1–10% incidence) include:

- Abnormal dreams

- Anisocoria

- Anorgasmia

- Anxiety

- Arthralgia (joint pain)

- Constipation

- Decreased or increased appetite

- Diarrhea

- Dilated pupils

- Dizziness

- Dry mouth

- Excessive sweating

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Impotence (erectile dysfunction)

- Libido changes

- Myalgia (muscular aches and pains)

- Paraesthesia (abnormal skin sensation)

- Restlessness

- Sinusitis (nasal congestion)

- Tremor

- Vomiting

- Yawning

Psychomotor effects

editThe most common effect is fatigue or somnolence, particularly in older adults,[50] although patients with pre-existing daytime sleepiness and fatigue may experience paradoxical improvement of these symptoms.[51]

Escitalopram has not been shown to affect serial reaction time, logical reasoning, serial subtraction, multitask, or Mackworth Clock task performance.[52]

Sexual dysfunction

editSome people experience persistent sexual side effects when taking SSRIs or after discontinuing them.[53] Symptoms of medication-induced sexual dysfunction from antidepressants include difficulty with orgasm, erection, or ejaculation.[53] Other symptoms may be genital anesthesia, anhedonia, decreased libido, vaginal lubrication issues, and nipple insensitivity in women. Rates are unknown, and there is no established treatment.[54]

Pregnancy

editAntidepressant exposure (including escitalopram) is associated with shorter duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g), and lower Apgar scores (by <0.4 points). Antidepressant exposure is not associated with an increased risk of spontaneous abortion.[55] There is a tentative association of SSRI use during pregnancy with heart problems in the baby.[56] The advantages of their use during pregnancy may thus not outweigh the possible negative effects on the baby.[56]

Withdrawal

editEscitalopram discontinuation, particularly abruptly, may cause certain withdrawal symptoms such as "electric shock" sensations,[57] colloquially called "brain shivers" or "brain zaps" by those affected. Frequent symptoms in one study were dizziness (44%), muscle tension (44%), chills (44%), confusion or trouble concentrating (40%), amnesia (28%), and crying (28%). Very slow tapering is recommended.[58] There have been spontaneous reports of discontinuation of escitalopram and other SSRIs and SNRIs, especially when abrupt, leading to dysphoric mood, irritability, agitation, anxiety, headache, lethargy, emotional lability, insomnia, and hypomania. Other symptoms such as panic attacks, hostility, aggression, impulsivity, akathisia (psychomotor restlessness), mania, worsening of depression, and suicidal ideation can emerge when the dose is adjusted down.[59]

Overdose

editExcessive doses of escitalopram usually cause relatively minor untoward effects, such as agitation and tachycardia. However, dyskinesia, hypertonia, and clonus may occur in some cases. Therapeutic blood levels of escitalopram are usually in the range of 20–80 μg/L but may reach 80–200 μg/L in the elderly, patients with hepatic dysfunction, those who are poor CYP2C19 metabolizers or following acute overdose. Monitoring of the drug in plasma or serum is generally accomplished using chromatographic methods. Chiral techniques are available to distinguish escitalopram from its racemate, citalopram.[42][60][61]

Interactions

editEscitalopram weakly inhibits CYP2D6, and hence may increase plasma levels of a number of CYP2D6 substrates such as aripiprazole, risperidone, tramadol, codeine, etc.[7] As escitalopram is only a weak inhibitor of CYP2D6, analgesia from tramadol may not be affected.[62] Escitalopram (at the maximum dose of 20 mg/day) has been found to increase peak levels of the CYP2D6 substrate desipramine by 40% and total exposure by 100%.[8] Likewise, it has been found to increase peak levels of the CYP2D6 substrate metoprolol by 50% and overall exposure by 82%.[8] Escitalopram does not inhibit CYP3A4, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, or CYP2E1.[7][8]

Exposure to escitalopram is increased moderately, by about 50%, when it is taken with omeprazole, a CYP2C19 inhibitor.[7] The authors of this study suggested that this increase is unlikely to be of clinical concern.[63] Combination of citalopram with fluoxetine or fluvoxamine resulted in increased exposure to the escitalopram enantiomer, owing to the strong inhibition of CYP2C19 and CYP2D6 by these agents.[8] Bupropion, a known strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, has been found to significantly increase citalopram plasma concentration and systemic exposure (peak levels increased by 30%, total exposure increased by 40%); as of April 2018[update] the interaction with escitalopram had not been studied, but some monographs warned of the potential interaction.[64] Citalopram did not affect the pharmacokinetics of bupropion or its metabolites in the study.[64]

Escitalopram should be taken with caution when using St. John's wort, ginseng, dextromethorphan (DXM), linezolid, tramadol, and other serotonergic drugs due to the risk of serotonin syndrome.[65][66] As an SSRI, escitalopram should not be given concurrently with MAOIs.[67]

Escitalopram, similarly to other SSRIs, may increase bleed risk with NSAIDs (ibuprofen, naproxen, mefenamic acid), antiplatelet drugs, anticoagulants, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin E, and garlic supplements due to escitalopram's inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation via blocking serotonin transporters on platelets.[68]

Escitalopram can also prolong the QT interval, and hence it is not recommended in patients that are concurrently on other medications that also have the ability to prolong the QT interval. These drugs include antiarrhythmics, antipsychotics, tricyclic antidepressants, some antihistamines (astemizole, mizolastine), macrolide and fluoroquinolone antibiotics, some 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (except palonosetron), and some antiretrovirals (ritonavir, saquinavir, lopinavir).[41]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

edit| Site | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.8–1.1 |

| NET | 7,800 |

| DAT | 27,400 |

| 5-HT1A | >1,000 |

| 5-HT2A | >1,000 |

| 5-HT2C | 2,500 |

| α1 | 3,900 |

| α2 | >1,000 |

| D2 | >1,000 |

| H1 | 2,000 |

| mACh | 1,240 |

| hERG | 2,600 (IC50) |

Escitalopram increases intrasynaptic levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by blocking the reuptake of the neurotransmitter into the presynaptic neuron. Over time, this leads to a downregulation of pre-synaptic 5-HT1A receptors, which is associated with an improvement in passive stress tolerance, and delayed downstream increase in expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, which may contribute to a reduction in negative affective biases.[71][72]

Of the SSRIs currently available, escitalopram has the highest selectivity for the serotonin transporter (SERT) compared to the norepinephrine transporter (NET), making the side-effect profile relatively mild in comparison to less-selective SSRIs.[67] In addition to its antagonist action at the orthosteric site of SERT, escitalopram also binds to an allosteric site on the transporter, thereby decreasing its own disassociation rate.[73] Escitalopram binds to this allosteric site at a greater affinity than other SSRIs.[74] The clinical relevance of this action is unknown.

Pharmacokinetics

editEscitalopram is a substrate of P-glycoprotein and hence P-glycoprotein inhibitors such as verapamil and quinidine may improve its blood brain barrier penetrability.[75] In a preclinical study in rats combining escitalopram with a P-glycoprotein inhibitor, its antidepressant-like effects were enhanced.[75]

Chemistry

editEscitalopram is the (S)-enantiomer (left-handed version) of the racemate citalopram, which is responsible for its name: escitalopram.[9] [76]

History

editEscitalopram was developed in cooperation between Lundbeck and Forest Laboratories. Its development was initiated in 1997, and the resulting new drug application was submitted to the US FDA in March 2001. The short time (3.5 years) it took to develop escitalopram can be attributed to the previous experience of Lundbeck and Forest with citalopram, which has similar pharmacology.[77]

Society and culture

editBrand names

editEscitalopram is sold under many brand names worldwide such as Cipralex, Lexapro, Lexam, Mozarin, Aciprex, Depralin, Ecytara, Elicea, Gatosil, Nexpram, Nexito, Nescital, Szetalo, Stalopam, Pramatis, Betesda, Scippa and Rexipra.[1][78]

Legal status

editThe FDA issued the approval of escitalopram for major depression in August 2002, and for generalized anxiety disorder in December 2003. In May 2006, the FDA approved a generic version of escitalopram by Teva.[79] In July 2006, the U.S. District Court of Delaware decided in favor of Lundbeck regarding a patent infringement dispute and ruled the patent on escitalopram valid.[80]

In 2006, Forest Laboratories was granted an 828-day (2 years and 3 months) extension on its US patent for escitalopram.[81] This pushed the patent expiration date from 7 December 2009, to 14 September 2011. Together with the 6-month pediatric exclusivity, the final expiration date was 14 March 2012.

Allegations of illegal marketing

editIn 2004, separate civil suits alleging illegal marketing of citalopram and escitalopram for use by children and teenagers by Forest were initiated by two whistleblowers: a physician named Joseph Piacentile and a Forest salesman named Christopher Gobble.[82] In February 2009, the suits were joined. Eleven states and the District of Columbia filed notices of intent to intervene as plaintiffs in the action.

The suits alleged that Forest illegally engaged in off-label promotion of Lexapro for use in children; hid the results of a study showing lack of effectiveness in children; paid kickbacks to physicians to induce them to prescribe Lexapro to children; and conducted so-called "seeding studies" that were, in reality, marketing efforts to promote the drug's use by doctors.[83][84] Forest denied the allegations[85] but ultimately agreed to settle with the plaintiffs for over $313 million.[86]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "Escitalopram". Drugs.com International. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 21 June 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Lexapro- escitalopram tablet, film coated; Lexapro- escitalopram solution". DailyMed. 17 November 2023. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

- ^ Human Medicines Division (September 2022). "Active substance(s): escitalopram" (PDF). List of nationally authorised medicinal products. European Medicines Agency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 September 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Pastoor D, Gobburu J (January 2014). "Clinical pharmacology review of escitalopram for the treatment of depression". Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 10 (1): 121–128. doi:10.1517/17425255.2014.863873. PMID 24289655.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rao N (2007). "The clinical pharmacokinetics of escitalopram". Clin Pharmacokinet. 46 (4): 281–290. doi:10.2165/00003088-200746040-00002. PMID 17375980.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "X". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ^ "Escitalopram (Lexapro) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2017.

- ^ "Protocol for switching patients from escitalopram to citalopram". NHS. 2015. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Escitalopram Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Medicines in the health system". Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. 2 July 2024. Retrieved 30 September 2024.

- ^ "Escitalopram oxalate". Australian Prescriber. 26: 146–151. 2003. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2003.107. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Lundbeck's Cipralex gets EU ok for OCD treatment". Reuters. 12 January 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Cipralex 10 mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". www.medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "The most effective antidepressants for adults revealed in major review". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 3 April 2018. doi:10.3310/signal-00580.

- ^ Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Chaimani A, Atkinson LZ, Ogawa Y, et al. (April 2018). "Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 391 (10128): 1357–1366. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7. PMC 5889788. PMID 29477251.

- ^ "Psychiatric drugs given to children and adolescents have been ranked in order of safety". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 1 September 2020. doi:10.3310/alert_40795. S2CID 241309451.

- ^ Solmi M, Fornaro M, Ostinelli EG, Zangani C, Croatto G, Monaco F, et al. (June 2020). "Safety of 80 antidepressants, antipsychotics, anti-attention-deficit/hyperactivity medications and mood stabilizers in children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders: a large scale systematic meta-review of 78 adverse effects". World Psychiatry. 19 (2): 214–232. doi:10.1002/wps.20765. PMC 7215080. PMID 32394557.

- ^ Ramsberg J, Asseburg C, Henriksson M (2012). "Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of antidepressants in primary care: a multiple treatment comparison meta-analysis and cost-effectiveness model". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e42003. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742003R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042003. PMC 3410906. PMID 22876296.

- ^ Cipriani A, Purgato M, Furukawa TA, Trespidi C, Imperadore G, Signoretti A, et al. (July 2012). "Citalopram versus other anti-depressive agents for depression". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012 (7): CD006534. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006534.pub2. PMC 4204633. PMID 22786497.

- ^ Favré P (February 2012). "[Clinical efficacy and achievement of a complete remission in depression: increasing interest in treatment with escitalopram]" [Clinical efficacy and achievement of a complete remission in depression: Increasing interest in treatment with escitalopram]. L'Encéphale (in French). 38 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1016/j.encep.2011.11.003. PMID 22381728.

- ^ Sicras-Mainar A, Navarro-Artieda R, Blanca-Tamayo M, Gimeno-de la Fuente V, Salvatella-Pasant J (December 2010). "Comparison of escitalopram vs. citalopram and venlafaxine in the treatment of major depression in Spain: clinical and economic consequences". Current Medical Research and Opinion. 26 (12): 2757–2764. doi:10.1185/03007995.2010.529430. PMID 21034375. S2CID 43179425.

- ^ Slee A, Nazareth I, Bondaronek P, Liu Y, Cheng Z, Freemantle N (February 2019). "Pharmacological treatments for generalised anxiety disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis". Lancet. 393 (10173): 768–777. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31793-8. PMID 30712879. S2CID 72332967.

- ^ Bech P, Lönn SL, Overø KF (February 2010). "Relapse prevention and residual symptoms: a closer analysis of placebo-controlled continuation studies with escitalopram in major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 71 (2): 121–129. doi:10.4088/JCP.08m04749blu. PMID 19961809.

- ^ Baldwin DS, Asakura S, Koyama T, Hayano T, Hagino A, Reines E, et al. (June 2016). "Efficacy of escitalopram in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis versus placebo". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 26 (6): 1062–1069. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.02.013. PMID 26971233.

- ^ Marjoribanks J, Brown J, O'Brien PM, Wyatt K (June 2013). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for premenstrual syndrome". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (6): CD001396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001396.pub3. PMC 7073417. PMID 23744611.

- ^ Clayton A, Keller A, McGarvey EL (March 2006). "Burden of phase-specific sexual dysfunction with SSRIs". Journal of Affective Disorders. 91 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.007. PMID 16430968.

- ^ "Lexapro prescribing information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C. "Antidepressants and Suicidality in Adults: Statistical Evaluation. (Presentation at Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee; December 13, 2006)". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ Stone MB, Jones ML (17 November 2006). "Clinical Review: Relationship Between Antidepressant Drugs and Suicidality in Adults" (PDF). Overview for 13 December Meeting of Pharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 11–74. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Levenson M, Holland C (17 November 2006). "Statistical Evaluation of Suicidality in Adults Treated with Antidepressants" (PDF). Overview for 13 December Meeting of Pharmacological Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC). FDA. pp. 75–140. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 March 2007. Retrieved 22 September 2007.

- ^ Khan A, Schwartz K (2007). "Suicide risk and symptom reduction in patients assigned to placebo in duloxetine and escitalopram clinical trials: analysis of the FDA summary basis of approval reports". Annals of Clinical Psychiatry. 19 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1080/10401230601163550. PMID 17453659.

- ^ Castro VM, Clements CC, Murphy SN, Gainer VS, Fava M, Weilburg JB, et al. (January 2013). "QT interval and antidepressant use: a cross sectional study of electronic health records". BMJ. 346: f288. doi:10.1136/bmj.f288. PMC 3558546. PMID 23360890.

- ^ a b c Lam RW (March 2013). "Antidepressants and QTc prolongation". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 38 (2): E5–E6. doi:10.1503/jpn.120256. PMC 3581598. PMID 23422053.

In summary, the effects of citalopram and other antidepressants in therapeutic doses on QTc are not likely to be of clinical relevance unless other known risk factors are present.

- ^ US FDA (15 December 2017). "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Revised recommendations for Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide) related to a potential risk of abnormal heart rhythms with high doses". US FDA. Retrieved 1 May 2024.

- ^ a b Danielsson B, Collin J, Nyman A, Bergendal A, Borg N, State M, et al. (March 2020). "Drug use and torsades de pointes cardiac arrhythmias in Sweden: a nationwide register-based cohort study". BMJ Open. 10 (3): e034560. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034560. PMC 7069257. PMID 32169926.

- ^ a b "Citalopram and escitalopram: QT interval prolongation—new maximum daily dose restrictions (including in elderly patients), contraindications, and warnings". Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. December 2011. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ^ a b van Gorp F, Whyte IM, Isbister GK (September 2009). "Clinical and ECG effects of escitalopram overdose". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 54 (3): 404–408. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.016. PMID 19556032.

- ^ Hasnain M, Howland RH, Vieweg WV (July 2013). "Escitalopram and QTc prolongation". Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 38 (4): E11. doi:10.1503/jpn.130055. PMC 3692726. PMID 23791140.

- ^ Leth-Møller KB, Hansen AH, Torstensson M, Andersen SE, Ødum L, Gislasson G, et al. (May 2016). "Antidepressants and the risk of hyponatremia: a Danish register-based population study". BMJ Open. 6 (5): e011200. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011200. PMC 4874104. PMID 27194321.

- ^ Naschitz JE (June 2018). "Escitalopram Dose-Dependent Hyponatremia". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 58 (6): 834–835. doi:10.1002/jcph.1091. PMID 29878443.

- ^ "Lexapro (escitalopram) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Cipralex 5, 10 and 20 mg film-coated tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. 2 October 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ "Escitalopram-Lupin Tablets (LUPIN AUSTRALIA PTY. LTD)" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Lupin Australia Pty Ltd. 21 December 2011. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ^ Mancano MA (May 2016). "Unequal Sized Pupils Due to Escitalopram; Adverse Events to Dietary Supplements Causing Emergency Department Visits; Compulsive Masturbation Due to Pramipexole; Metformin-Induced Lactic Acidosis Masquerading As an Acute Myocardial Infarction". Hospital Pharmacy. 51 (5). Thomas Land Publishers, Inc.: 358–361. doi:10.1310/hpj5105-358. PMC 4896342. PMID 27303087.

- ^ Lenze EJ (20 May 2009). "Escitalopram Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder in Older Adults—Reply". JAMA. 301 (19): 1987. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.652. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ^ Shen J, Hossain N, Streiner DL, Ravindran AV, Wang X, Deb P, et al. (November 2011). "Excessive daytime sleepiness and fatigue in depressed patients and therapeutic response of a sedating antidepressant". Journal of Affective Disorders. 134 (1–3): 421–426. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.047. PMID 21616541.

- ^ Rosekind MR, Gregory KB, Mallis MM (December 2006). "Alertness management in aviation operations: enhancing performance and sleep". Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine. 77 (12): 1256–1265. doi:10.3357/asem.1879.2006. PMID 17183922.

- ^ a b American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. pp. 446–449. ISBN 9780890425558.

- ^ Bala A, Nguyen HM, Hellstrom WJ (January 2018). "Post-SSRI Sexual Dysfunction: A Literature Review". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 6 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.07.002. PMID 28778697.

- ^ Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, Vonderporten EH, Roerecke M, Rehm J, et al. (April 2013). "Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA Psychiatry. 70 (4): 436–443. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684. PMID 23446732. S2CID 2065578.

- ^ a b Gentile S (1 July 2015). "Early pregnancy exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, risks of major structural malformations, and hypothesized teratogenic mechanisms". Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 11 (10): 1585–1597. doi:10.1517/17425255.2015.1063614. PMID 26135630. S2CID 43329515.

- ^ Prakash O, Dhar V (June 2008). "Emergence of electric shock-like sensations on escitalopram discontinuation". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 28 (3): 359–360. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181727534. PMID 18480703.

- ^ Yasui-Furukori N, Hashimoto K, Tsuchimine S, Tomita T, Sugawara N, Ishioka M, et al. (June 2016). "Characteristics of Escitalopram Discontinuation Syndrome: A Preliminary Study". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 39 (3): 125–127. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000139. PMID 27171568. S2CID 45460237.

- ^ "Lexapro (Escitalopram Oxalate) Drug Information: Warnings and Precautions - Prescribing Information at RxList". Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2015.

- ^ Haupt D (October 1996). "Determination of citalopram enantiomers in human plasma by liquid chromatographic separation on a Chiral-AGP column". Journal of Chromatography. B, Biomedical Applications. 685 (2): 299–305. doi:10.1016/s0378-4347(96)00177-6. PMID 8953171.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of toxic drugs and chemicals in man (8th ed.). Foster City, Ca: Biomedical Publications. pp. 552–553. ISBN 978-0962652370.

- ^ Noehr-Jensen L, Zwisler ST, Larsen F, Sindrup SH, Damkier P, Brosen K (December 2009). "Escitalopram is a weak inhibitor of the CYP2D6-catalyzed O-demethylation of (+)-tramadol but does not reduce the hypoalgesic effect in experimental pain". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 86 (6): 626–633. doi:10.1038/clpt.2009.154. PMID 19710642. S2CID 29063004.

- ^ Malling D, Poulsen MN, Søgaard B (September 2005). "The effect of cimetidine or omeprazole on the pharmacokinetics of escitalopram in healthy subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 60 (3): 287–290. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02423.x. PMC 1884771. PMID 16120067.

- ^ a b "Drug interactions between bupropion and Lexapro". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Karch A (2006). 2006 Lippincott's Nursing Drug Guide. Philadelphia, Baltimore, New York, London, Buenos Aires, Hong Kong, Sydney, Tokyo: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-58255-436-5.

- ^ Boyer EW, Shannon M (March 2005). "The serotonin syndrome". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (11): 1112–1120. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041867. PMID 15784664.

- ^ a b Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

- ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Sanchez C, Reines EH, Montgomery SA (July 2014). "A comparative review of escitalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline: Are they all alike?". International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (4): 185–196. doi:10.1097/YIC.0000000000000023. PMC 4047306. PMID 24424469.

- ^ Chae YJ, Jeon JH, Lee HJ, Kim IB, Choi JS, Sung KW, et al. (January 2014). "Escitalopram block of hERG potassium channels". Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology. 387 (1): 23–32. doi:10.1007/s00210-013-0911-y. PMID 24045971. S2CID 15062534.

- ^ Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ (September 2017). "Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 31 (9): 1091–1120. doi:10.1177/0269881117725915. PMC 5606297. PMID 28858536.

- ^ Harmer CJ, Duman RS, Cowen PJ (May 2017). "How do antidepressants work? New perspectives for refining future treatment approaches". The Lancet. Psychiatry. 4 (5): 409–418. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30015-9. PMC 5410405. PMID 28153641.

- ^ Zhong H, Haddjeri N, Sánchez C (January 2012). "Escitalopram, an antidepressant with an allosteric effect at the serotonin transporter--a review of current understanding of its mechanism of action". Psychopharmacology. 219 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2463-5. PMID 21901317.

- ^ Mansari ME, Wiborg O, Mnie-Filali O, Benturquia N, Sánchez C, Haddjeri N (February 2007). "Allosteric modulation of the effect of escitalopram, paroxetine and fluoxetine: in-vitro and in-vivo studies". The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 10 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1017/S1461145705006462. PMID 16448580.

- ^ a b O'Brien FE, O'Connor RM, Clarke G, Dinan TG, Griffin BT, Cryan JF (October 2013). "P-glycoprotein inhibition increases the brain distribution and antidepressant-like activity of escitalopram in rodents". Neuropsychopharmacology. 38 (11): 2209–2219. doi:10.1038/npp.2013.120. PMC 3773671. PMID 23670590.

- ^ "Citalopram and escitalopram". Meyler's Side Effects of Drugs (6 ed.). Elsevier. 2016. p. 383.

- ^ "2000 Annual Report. p 28 and 33" (PDF). Lundbeck. 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ "Mozarin, zamienniki i podobne rodukty". Gdziepolek.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Miranda H. "FDA OKs Generic Depression Drug – Generic Version of Lexapro Gets Green Light". WebMD. Archived from the original on 5 January 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Laforte ME (14 July 2006). "US court upholds Lexapro patent". FirstWord. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Forest Laboratories Receives Patent Term Extension for Lexapro" (Press release). PRNewswire-FirstCall. 2 March 2006. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Frankel A (27 February 2009). "Forest Laboratories: A Tale of Two Whistleblowers". The American Lawyer. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009.

- ^ "United States of America v. Forest Laboratories" (PDF). US District Court for the district of Massachusetts. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2009.

- ^ Meier B, Carey B (25 February 2009). "Drug Maker Is Accused of Fraud". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020.

- ^ "Forest Laboratories, Inc. Provides Statement in Response to Complaint Filed by U.S. Government". Forest press-release. 26 February 2009. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- ^ "Drug Maker Forest Pleads Guilty; To Pay More Than $313 Million to Resolve Criminal Charges and False Claims Act Allegations". www.justice.gov. 15 September 2010. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

External links

edit- Harris G (1 September 2009). "A Peek at How Forest Laboratories Pushed Lexapro". The New York Times.