Fort Dix, the common name for the Army Support Activity (ASA) located at Joint Base McGuire–Dix–Lakehurst, is a United States Army post. It is located 16.1 miles (25.9 km) south-southeast of Trenton, New Jersey. Fort Dix is under the jurisdiction of the Air Force Air Mobility Command. As of the 2020 U.S. census, Fort Dix census-designated place (CDP) had a total population of 7,716,[9][10][11][12] of which 5,951 were in New Hanover Township, 1,765 were in Pemberton Township, and none were in Springfield Township (though portions of the CDP are included there).[12]

| Fort Dix | |

|---|---|

| Located near: Trenton, New Jersey | |

U.S. Army combat training at Fort Dix in January 2008 | |

| Coordinates | 40°01′09″N 74°31′22″W / 40.01917°N 74.52278°W |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1917 |

| In use | 1917–present |

Army Support Activity Fort Dix | |

|---|---|

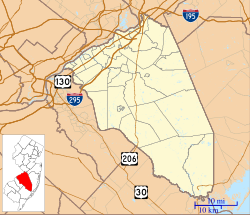

Fort Dix's location in Burlington County, New Jersey. Inset: Location of Burlington County in New Jersey | |

| Coordinates: 40°00′22″N 74°36′40″W / 40.006°N 74.611°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Burlington |

| Township | New Hanover Pemberton Springfield |

| Area | |

• Total | 10.34 sq mi (26.78 km2) |

| • Land | 10.21 sq mi (26.45 km2) |

| • Water | 0.13 sq mi (0.33 km2) 1.22% |

| Elevation | 141 ft (43 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 6,508 |

| • Density | 637.16/sq mi (246.02/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (Eastern (EDT)) |

| ZIP Code | 08640[4] |

| Area code(s) | 609, 640 |

| FIPS code | 34-24300[5][6][7] |

| GNIS feature ID | 02389104[5][8] |

| Website | www |

Established in 1917, Fort Dix was in 2009 combined with adjoining U.S. Air Force and Navy facilities to become Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (JB MDL) in 2009. However, it remains commonly known as "Fort Dix", "ASA Dix", or "Dix".

During 2015 to 2016, Colonel Shelley Balderson was commander, making her the first female commander of Fort Dix in the base's century-long history.

Overview

editFort Dix was established on 16 July 1917, as Camp Dix, named in honor of Major General John Adams Dix, a veteran of the War of 1812 and the American Civil War, and a former U.S. Senator, U.S. Secretary of the Treasury, and Governor of New York.[13] Camp Dix was home to the 153rd Depot Brigade. The role of World War I depot brigades was to receive recruits and draftees, then organize them and provide them with uniforms, equipment, and initial military training. Depot brigades also received soldiers returning home at the end of the war and carried out their mustering out and discharges.

Dix has a history of mobilizing, training, and demobilizing soldiers from as early as World War I through April 2015, when Fort Bliss and Fort Hood in Texas assumed full responsibility for that mission. In 1978, the first female recruits entered basic training at Fort Dix. In 1991, Dix trained Kuwaiti civilians in basic military skills so they could take part in their country's liberation.[13]

Dix ended its active U.S. Army training mission in 1991 due to Base Realignment and Closure Commission recommendations, which ended its command by a two-star general. Presently, it serves as a joint training site for all military components and all services.

In 2009, Fort Dix and the adjacent Air Force and Naval facilities were consolidated into a single secure facility, called Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst. The supporting component is the U.S. Air Force, and base operations are executed by the 87th Air Base Wing, which provides installation management to all of the joint base while both the Navy and Army retain command and control of their missions, personnel, equipment, and component-specific services. Neither the Navy nor the Army base is subordinate to the Joint Base; each is simply supported by the joint base in base operations such as utilities, child-care centers, gyms, and other services, but each one reports through its own service-specific command chain and has its own commander (the Navy a captain and the Army a colonel). The commanders of both Fort Dix and Lakehurst serve also as deputy joint base commanders.[14]

Units assigned

edit- 1st Brigade, Atlantic Training Division, 84th Training Command[13]

- 99th Readiness Division[13]

- 174th Infantry Brigade[13]

- 305th Aerial Port Squadron

- Fleet Logistics Squadron (VR-64)[13]

- Marine Aircraft Group 49[13]

- Military Entrance Processing Station[13]

- Navy Operational Support Center[13]

- NCO Academy[13]

- United States Air Force Expeditionary Center[13]

- USCG Atlantic Strike Team[13]

History

edit- See footnote[15]

Construction began in June 1917. Camp Dix, as it was known at the time, was a training and staging ground for units during World War I. Though the camp was an embarkation camp for the New York Port of Embarkation, it did not fall under the direct control of that command, with the War Department retaining direct jurisdiction.[16] The camp became a demobilization center after the war. Between the World Wars, Camp Dix was a reception, training, and discharge center for the Civilian Conservation Corps. Camp Dix became Fort Dix on 8 March 1939, and the installation became a permanent Army post. During and after World War II, the fort served the same purpose as in the First World War, serving as a training and staging ground during the war and a demobilization center after the war.

After victory in Europe, arrangements were made to return prisoners of war to their home countries. 154 Soviet citizens who had been captured in German uniform were brought from Camp Ruston in Louisiana to Fort Dix in preparation for their return. On 29 June 1945, having learned of the plan, they rioted, attempting to provoke their guards to shoot them. Three hanged themselves. Seven proved they were not Soviet citizens, and the rest were shipped out on 31 August.[17]

On 15 July 1947, Fort Dix became a basic-training center and the home of the 9th Infantry Division. In 1954, the 9th moved out and the 69th Infantry Division made the fort home until it was deactivated on 16 March 1956. During the Vietnam War, rapid expansion took place. A mock Vietnamese village was constructed, and soldiers received Vietnam-specific training before being deployed. Since Vietnam, Fort Dix has sent soldiers to Operation Desert Shield, Desert Storm, Bosnia, Afghanistan, and Iraq.

U.S. Coast Guard site

editThe Atlantic Strike Team (AST) of the U.S. Coast Guard is based at Fort Dix. As part of the Department of Homeland Security, the AST is responsible for responding to oil-pollution and hazardous-materials release incidents to protect public health and the environment.[18][19]

Federal Correctional Institution

editFort Dix is also home to Fort Dix Federal Correctional Institution, the largest single federal prison. It is a low-security installation for male inmates located within the military installation. As of 19 November 2009, it housed 4,310 inmates, and a minimum-security satellite camp housed an additional 426.[20]

Mission realignment

editKnowing that Fort Dix was on a base closure list, the U.S. Air Force (USAF) attempted to save the U.S. Army post during 1987. The USAF moved the Security Police (SP) Air Base Ground Defense school from Camp Bullis, Texas, to Dix in fall 1987. Putting 50–100 SP trainees on a commercial flight from San Antonio, Texas, to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, every few weeks was eventually realized to be not cost effective, so the school was later moved back to Camp Bullis.

Fort Dix was an early casualty of the first base realignment and closure process in the early 1990s, after having lost its traditional basic-training mission, but advocates attracted Army Reserve interest in keeping the 31,000-acre (13,000 ha) post as a training reservation. With the reserves, and millions of dollars for improvements, Fort Dix has grown again to employ 3,000. As many as 15,000 troops train there on weekends, and the post has been a major mobilization point for reserve and National Guard troops since the September 11 attacks on New York City and Washington, D.C.

Fort Dix has completed its realignment from an individual training center to a FORSCOM Power Projection Platform for the Northeastern United States under the command and control of the Army's Installation Management Command. Primary missions include training and providing regional base operations support to on-post and off-post active component and U.S. Army Reserve units, soldiers, families, and retirees. Fort Dix supported more than 1.1 million man-days of training in 1998. More than 13,500 persons, on average, live or work within the garrison and its tenant organizations. Devens Reserve Force Training Area in Massachusetts is a subinstallation of the ASA.

2005 realignments

editIn 2005, the US Department of Defense announced that Fort Dix would be affected by a base realignment and closure. For base operations support, it became part of Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, N.J. It was the first base of its kind in the United States and is the Department of Defense's only three-service joint base. ASA, Fort Dix occupies and supports all training across 31,000 of the joint base's 42,000 acres.

Attack plots

edit1970

editIn 1970, the Weather Underground planned to detonate a nail bomb at a noncommissioned officers' dance at the base to "bring the war home" and "give the United States and the rest of the world a sense that this country was going to be completely unlivable if the United States continued in Vietnam." The plot failed the morning of the dance, when a bomb under construction exploded at the group's Greenwich Village, New York City, townhouse, killing three members of the group.[21]

2007

editOn 8 May 2007, six individuals, mostly ethnic Albanian Muslims,[22] were arrested for plotting an attack against Fort Dix and the soldiers within. The men are believed to be Islamic radicals who may have been inspired by the ideologies of al-Qaeda.[23] The men allegedly planned to storm the base with automatic weapons in an attempt to kill as many soldiers as possible.[22] The men faced charges of conspiracy to kill U.S. soldiers.[24]

1969 stockade riot

editOn 5 June 1969, 250 men imprisoned in the military stockade rioted. The prisoners called it a rebellion and cited grievances including "unsanitary conditions", overcrowding, starvation, beatings, being chained to chairs, forced confessions and participation in an unjust war. The Army initially called it a "disturbance" caused by a small number of "instigators" and "troublemakers", but soon charged 38 soldiers with riot and inciting to riot. The antiwar movement, which had been increasingly recognizing and supporting resistance to the war within the military, quickly moved to defend the rebels/rioters and those the Army singled out for punishment. Soon the slogan "Free the Fort Dix 38" was heard in antiwar speeches, written about in underground newspapers and leaflets, and demonstrations were planned.[25][26][27]

Due to public backlash against the military's treatment of the prisoners, only five of the original 38 were brought before a general court-marital on serious charges. Most had their charges dropped entirely, while nine faced a special court-martial, the military equivalent of misdemeanor court. Four of those were convicted of misdemeanor participation in a riot and the other five acquitted.[28][29] Of the five singled out for general courts-martial, one was acquitted completely while four were discharged with varying sentences including hard labor.[26][30]

Ultimate Weapon monument

editIn 1957, during their leisure hours, Specialist 4 Steven Goodman, assisted by PFC Stuart Scherr, made a small clay model of a charging infantryman. Their tabletop model was spotted by a public-relations officer, who brought it to the attention of Deputy Post Commander Bruce Clarke, who suggested the construction of a larger statue to serve as a symbol of Fort Dix.[31] Goodman and Scherr, who had studied industrial arts together in New York City and were classified by the Army as illustrators, undertook the project under the management of Sergeant Major Bill Wright. Operating on a limited budget, and using old railroad track, Bondo, and other available items, they created a 12-foot figure of a charging infantryman in full battle dress,[31] representing no particular race or ethnicity.[32]

By 1988, years of weather had taken a toll on the statue, and a restoration campaign raised over $100,000. Under the auspices of Goodman and the Fort Dix chapter of the Association of the United States Army, the statue was recast in bronze and its concrete base was replaced by black granite.[33]

The statue stands 25 feet tall at the entrance to Infantry Park. Its inscription reads

This monument is dedicated to

the only indispensable instrument of war,

The American Soldier—

The Ultimate Weapon

"If they are not there,

you don't own it."

17 August 1990

Geography

editAccording to the U.S. Census Bureau, Fort Dix had a total area of 10.389 square miles (26.909 km2), of which 0.127 square mile (0.329 km2) is covered by water (1.22%).[5][34]

Climate

editThe climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen climate classification, Fort Dix has a humid subtropical climate, Cfa on climate maps.[35]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 26,290 | — | |

| 1980 | 14,297 | −45.6% | |

| 1990 | 10,205 | −28.6% | |

| 2000 | 7,464 | −26.9% | |

| 2010 | 7,716 | 3.4% | |

| 2020 | 6,508 | −15.7% | |

| Population sources: 1970–1980[36] 1990-2010[12] 2000[37] 2010[9] 2020[3] | |||

2010 census

editThe 2010 United States census counted 7,716 people, 784 households, and 590 families in the CDP. The population density was 751.9 per square mile (290.3/km2). There were 898 housing units at an average density of 87.5 per square mile (33.8/km2). The racial makeup was 52.57% (4,056) White, 34.47% (2,660) Black or African American, 0.67% (52) Native American, 1.91% (147) Asian, 0.30% (23) Pacific Islander, 6.07% (468) from other races, and 4.02% (310) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 21.47% (1,657) of the population.[9]

Of the 784 households, 59.1% had children under the age of 18; 63.8% were married couples living together; 8.7% had a female householder with no husband present and 24.7% were non-families. Of all households, 15.1% were made up of individuals and 0.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.05 and the average family size was 3.56.[9]

12.1% of the population were under the age of 18, 4.2% from 18 to 24, 50.2% from 25 to 44, 30.9% from 45 to 64, and 2.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38.9 years. For every 100 females, the population had 522.8 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older there were 757.5 males.[9]

Transportation

editNew Jersey Route 68 links Fort Dix to U.S. Route 206 near the latter's interchanges with the New Jersey Turnpike, U.S. Route 130, and Interstate 295. New Jersey Transit provides service to and from Philadelphia on the 317 route.[38]

Education

editThe U.S. Census Bureau lists "Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst" in Burlington County as having its own school district.[39] Students attend area school district public schools, as the Department of Defense Education Activity does not operate any schools on that base. Students on McGuire and Dix may attend one of the following in their respective grade levels, with all siblings in a family taking the same choice: North Hanover Township School District (PK-6), Northern Burlington County Regional School District (7-12), and Pemberton Township School District (K-12).[40]

The Pemberton district operates Fort Dix Elementary School, located on-post.[41]

In prior years, Pemberton was the sole school district for Fort Dix. In 1988, 23% of the students in that district were from military families.[42] In 1997, plans were made to shift the students, numbering around 700, to North Hanover schools. Pemberton school officials were against that move.[43]

Pop-culture references

editFort Dix is the home base setting in Cinemaware's 1988 C64 and Nintendo video game Rocket Ranger; the game is based on an alternate World War II scenario, wherein the Nazis discover lunarium, which could allow them to win the war unless a young American scientist stops them.[44]

Notable people

edit- Jay Berger (born 1966), a former professional tennis player, reached a highest world ranking of number seven.[45]

- Bruce Hill (born 1964), is former wide receiver for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

- Jim Riggleman (born 1952) is a former professional baseball player and manager.[46]

- Mel Brooks (born 1926) is an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker.[47]

- Franco Harris (1950-2022) was a National Football League Hall of Fame running back, born in Fort Dix.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "Fort Dix Census Designated Place". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 17 June 2013.

- ^ a b QuickFacts Fort Dix CDP, New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed June 20, 2023.

- ^ Look Up a ZIP Code for Fort Dix, NJ, United States Postal Service. Accessed 17 June 2013.

- ^ a b c Gazetteer of New Jersey Places, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 21 July 2016.

- ^ U.S. Census website, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 4 September 2014.

- ^ Geographic codes for New Jersey, Missouri Census Data Center. Accessed June 9, 2023.

- ^ US Board on Geographic Names, United States Geological Survey. Accessed 4 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e DP-1 - Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data for Fort Dix CDP, New Jersey Archived 12 February 2020 at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 17 June 2013.

- ^ GCT-PH1 - Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County -- County Subdivision and Place from the 2010 Census Summary File 1 for Burlington County, New Jersey Archived 12 February 2020 at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 8 June 2013.

- ^ 2006-2010 American Community Survey Geography for New Jersey, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 8 June 2013.

- ^ a b c New Jersey: 2010 - Population and Housing Unit Counts - 2010 Census of Population and Housing (CPH-2-32), United States Census Bureau, p. III-5, August 2012. Accessed 8 June 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst Dix". Newpreview.afnews.af.mil. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Mission Partners Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine webpage. Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst (JB MDL) official website. Accessed 18 June 2010.

- ^ John Adams Dix and the history of Fort Dix Archived 27 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine webpage (ASA-Dix (U.S. Army Support Activity) official website). Accessed 18 June 2010.

- ^ Huston, James A. (1966). The Sinews of War: Army Logistics 1775—1953. Army Historical Series. Washington, DC: Center Of Military History, United States Army. p. 346. ISBN 9780160899140. LCCN 66060015. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ^ "1945: The Fort Dix POW riot". www.capitalcentury.com. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "Atlantic Strike Team (AST)". Uscg.mil. 22 December 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Nash, Margo (2 July 2000). "A Coast Guard Team Based (Where Else?) in the Pine Barrens". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ^ "Federal Bureau of Prisons Weekly Population Report". Bop.gov. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "The Weather Underground". Time. 7 October 2008. Archived from the original on 10 October 2008.

- ^ a b Russakoff, Dale; Eggen, Dan (8 May 2007). "Fort Dix Targeted in Terror Plot". Washington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ "6 held on terror conspiracy charges in N.J." NBC News. 8 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ "6 Arrested In New Jersey Terror Plot". CBS. 8 May 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2007.

- ^ "150 Riot at Ft. Dix Stockade; Fires Set and Windows Broken". The New York Times. 6 June 1969.

Prisoners in the Fort Dix stockade set mattress fires, smashed windows and hurled footlockers, beds, and other equipment tonight in what an Army spokesman characterized as a 'disturbance.'

- ^ a b Crowell, Joan (1974). Fort Dix Stockade: Our Prison Camp Next Door. Berlin: Links. p. 9. ISBN 0-8256-3035-5.

- ^ Wallechinsky, David (1975). The People's Almanac. Garden City: Doubleday. p. 68. ISBN 0-385-04060-1.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (7 December 1969). "Third G.I. on Trial in Ft. Dix Rioting". The New York Times.

- ^ Investigation of Students for a Democratic Society: Hearings, Ninety-First Congress, First-Session. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1970. pp. 2437–2447. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ "Free the Ft. Dix 38!". content.wisconsinhistory.org/digital/collection. Wisconsin Historical Society: GI Press Collection. The Shakedown.

- ^ a b "Stuart Scherr and Steven Goodman, Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. Universal Match Corporation and United States of America, Defendants-Appellees., 417 F.2d 497 (2nd Cir. 1969)". Vlex.com. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ "Historical Marker Database, The Ultimate Weapon". Hmdb.org. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ The Ultimate Weapon - soldier's artwork stands for military tradition Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 4 September 2014.

- ^ Climate Summary for Fort Dix

- ^ Staff. 1980 Census of Population: Number of Inhabitants United States Summary, p. 1-140. United States Census Bureau, June 1983. Accessed 17 June 2013.

- ^ DP-1 - Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000 from the Census 2000 Summary File 1 (SF 1) 100-Percent Data for Fort Dix CDP, New Jersey Archived 12 February 2020 at archive.today, United States Census Bureau. Accessed 8 June 2013.

- ^ Burlington County Bus / Rail Connections, New Jersey Transit, backed up by the Internet Archive as of 26 June 2010. Accessed 17 June 2013.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Burlington County, NJ" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 7 August 2022. - Text list

- ^ "Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst Education". Military One Source. Retrieved 7 August 2022. - This is a .mil site.

- ^ "Welcome to Ft. Dix Elementary School". Ft. Dix Elementary School. Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- ^ Johnston, David; Frush, Charlie (30 December 1988). "Assessing the blow at N.J.'s biggest base". Philadelphia Inquirer. Philadelphia. pp. 1-A, 11-A. - Clipping of first and of second page at Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Pemberton could lose 700 students". Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey. 15 August 1997. p. 2B. - Clipping from Newspapers.com.

- ^ Farrell, Andrew. "Future's back to good old days", The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 October 1988. Accessed 17 June 2013. "Cinemaware's new game, Rocket Ranger, brings back the memories and pays tribute to old-time greats. ... Commands can only be issued from home base in Fort Dix, New Jersey."

- ^ "Tennis", New York Daily News, 1 September 1988. Accessed 9 January 2021, via Newspapers.com. "Next up for Lendl is Jay Berger, a 21-year-old who was born in Fort Dix, N.J. but now lives in Plantation, Fla."

- ^ Newberry, Paul, via Associated Press. "Braves make major splash; Riggleman hired as Mets bench coach", The Times-Tribune, 27 November 2018. Accessed 9 January 2021, via Newspapers.com. "Jim Riggleman, a 66-year-old veteran of 13 seasons as a major league manager, was hired by the New York Mets as bench coach for Mickey Callaway. ... Riggleman, a native of Fort Dix, New Jersey, also managed the Chicago Cubs (1995-99), Seattle (2008) and Washington (2009-11)."

- ^ Brooks, Mel (30 November 2021). All About Me!: My Remarkable Life in Show Business. Penguin Random House. ISBN 9780593159118.[page needed]

External links

edit- Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst official website

- ASA - Dix official website (U.S. Army Support Activity)

- Fort Dix Command Chaplain Section. Army Support Activity–Dix (ASA-Dix) official website

- IMCOM Atlantic Region official website (U.S. Army Installation Management Command)

- Details on the Ultimate Weapon monument from the Fort Dix website