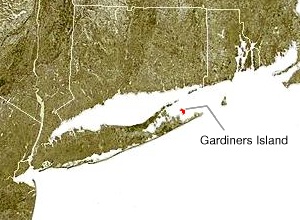

Gardiner's Island is a small island in the Town of East Hampton, New York, in Eastern Suffolk County. It is located in Gardiner's Bay between the two peninsulas at the east end of Long Island. It is 6 miles (9.7 km) long, 3 miles (4.8 km) wide and has 27 miles (43 km) of coastline.

| |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Gardiners Bay |

| Total islands | 2 |

| Area | 5.184 sq mi (13.43 km2) |

| Administration | |

United States | |

| State | New York |

| County | Suffolk County |

The island has been owned by the Gardiner family and their descendants since 1639 when Lion Gardiner purchased it from the Montaukett chief Wyandanch.[1] At 5.19 square miles (13.4 km2), it is one of the largest privately owned islands in the United States, though slightly smaller than Naushon Island in Massachusetts, owned by the Forbes family.[2][a]

Geography

editThe island is 5.19 square miles (13.4 km2) in size.[4] Its 3,318 acres include more than 1,000 acres (400 ha) of old growth forest and another 1,000 acres (405 ha) of meadows. Many of the buildings date back to the 17th century. In 1989, the island was said to be worth $125 million.[5]

The island has the largest stand of white oak in the American Northeast. Other trees include swamp maple, wild cherry and birch. The island is home to New York state's largest colony of ospreys and is one of the few locations in the world where they build their nests on the ground, as the birds have no natural predators on the island.

Structures

editIn addition to the family mansion and the Gardiners Island Windmill, structures on the island include a private airstrip on the south side and a carpenter's shed said to have been built in 1639.

The shed's claim to being the oldest surviving wood-frame structure in New York state is disputed by some. No primary sources authenticating its construction have been produced, only a description by Robert David Lion Gardiner in a 1976 documentary about the island.[6][7] An earlier source that describes the settlement and early life on the island makes no mention of the shed.[8]

History

editFirst English settlement in New York

editThe island was settled by Lion Gardiner in 1639, who moved there with his family from the Connecticut Colony. He reportedly purchased the island from the local Montaukett people for "a large black dog, some powder and shot, and a few Dutch blankets."[8] The Indians called the island Manchonake, while Gardiner initially called it Isle of Wight, because it reminded him of the Isle of Wight in England.[9] The Montauketts gave Gardiner the title, at least in part because of his support for them in the Pequot War.

The island was not part of the Connecticut Colony or the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations of the British, nor was it a part of the Dutch colony of New Netherlands. It evidently fell under the jurisdiction of Earl of Stirling, William Alexander, who had been given Long Island by the King of England in 1636 and required Gardiner to gain his approval of the land grant through his agent James Farrett. It has been privately owned by Gardiner's descendants for 385 years.

The royal patent of 1639 gave Gardiner the "right to possess the land forever", with the island being declared a proprietary colony[citation needed] Gardiner was given the title of Lord of the Manor and the attenuating privileges of governorship.

On October 5, 1665, after the British had taken over New Netherlands and established the Province of New York, and it had been established that Long Island would not be part of the Connecticut Colony, Richard Nicolls, the first Governor of the Province, issued a new patent to Lion Gardiner's son David.

In 1688, when Governor Thomas Dongan granted a patent formally establishing the East Hampton municipal government, there was an attempt to annex the island, which the Gardiners successfully resisted.[10] Gardiner's Island would remain independent of outside municipal jurisdiction until after the American Revolution, when it was formally annexed to East Hampton.

Gardiner established a plantation on the island, raising corn, wheat, fruit, tobacco, and livestock.

Captain Kidd

editPrivateer William Kidd stopped at the island in June 1699 while sailing to Boston to answer charges of piracy. With the permission of the island's proprietor, he buried a chest, a box of gold, and two boxes of silver in a ravine between Bostwick's Point and the Manor House. Indicating to Mrs. Gardiner that the box of gold was intended for the Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Lord Bellomont, Kidd gave Mrs. Gardiner a length of gold cloth,[11] captured from a Moorish ship off the coast of India,[b] and a sack of sugar in thanks for her hospitality.

A legend developed that Kidd warned that if the treasure was not there when he returned he would kill the Gardiners, though trial testimony given by John Gardiner on July 17, 1699, makes no mention of any threats, and Kidd's conduct appears to have been quite civil.[13] Kidd was tried in Boston, and Gardiner was ordered by Governor Bellomont to deliver the treasure as evidence. The booty included gold dust, bars of silver, Spanish dollars, rubies, diamonds, candlesticks, and porringers. Gardiner kept one of the diamonds which he later gave to his daughter. A plaque on the island marks the spot where the treasure was buried.[14][15][16]

American Revolution

editThe Gardiners sided with the colonists during the American Revolution. A fleet of thirteen British ships sailed into the island's Cherry Harbor and began foraging and pillaging its manor house at will; they were planning to turn it into a private hunting preserve. Among the British interlopers were Henry Clinton and John André. At one point, Major André and Gardiner's son Nathaniel Gardiner exchanged toasts on the island. Nathaniel Gardiner was a surgeon for the New Hampshire Continental Infantry. He was the American surgeon who later attended to André before he was executed for spying with Benedict Arnold.[17]

Following the revolution, the island was formally brought under East Hampton town jurisdiction.

War of 1812

editDuring the War of 1812, a British fleet of seven ships of the line and several smaller frigates anchored in Cherry Harbor and conducted raids on American shipping through Long Island Sound. Crews would come ashore for provisions, which were purchased at market prices. During one of the British excursions, Americans captured some of the crew. The British came to arrest then owner John Lyon Gardiner, who, being a delicate man, adopted the "green room defense", where he stayed in a bed with green curtains surrounded by medicine to make him look feeble.[11] The British, not wanting a sick man on board, let him be.[17]

The British were to bury several personnel on the island during the course of the war. Some of the British fleet that burned Washington assembled in the harbor in 1814.[18]

Gardiner's supply boats were manned by slaves during the war, and this made it easier for them to pass through British lines.[how?] After the State of New York abolished slavery in 1827, many of the freed Gardiner slaves went to live in Freetown, just north of East Hampton village.[17]

Remainder of 19th century

editJulia Gardiner, who was to become President John Tyler's second wife and First Lady in 1844, was born on the island in 1820.[11]

Gardiners Point Island is an tiny islet in Block Island Sound that is the former location of both the Gardiners Island Lighthouse and Fort Tyler. Once a peninsula of Gardiner's Island, it is the location of a 14 acres (5.7 ha) parcel the federal government purchased from the Gardiners in 1851 for $400. Work on the lighthouse began in 1854, with the lighthouse being first lit in 1855 following a $7,000 construction expenditure. It was a 27-foot (8.2 m) square 1½ story brick building with a sixth order Fresnel Lens producing a fixed white light located 33 feet (10 m) above sea level.

A March 1888 nor'easter caused a break in the peninsula, permanently turning the point into an island (but leaving it under the jurisdiction of East Hampton). Between 1890 and 1893 the island was shrinking at the rate of 10+3⁄4 feet (3.3 m) per year. On March 7, 1894, the lighthouse was abandoned and shortly afterward fell into the ocean. A lighted buoy was then moored ¼ miles northeast of the lighthouse.

During the Spanish–American War, the War Department appropriated $500,000 to build the Fort Tyler battery on the island. One source states it was named in General Order 194 of 27 December 1904 for Daniel Tyler, a general and Civil War veteran who died in 1882.[19][better source needed] Another claim is that it was named for former President John Tyler (1841–1845), who married Julia Gardiner Tyler, born on Gardiners Island.[citation needed]

The fort was intended to consist of Battery Edmund Smith, with emplacements for two 8-inch M1888 disappearing guns and two 5-inch M1900 guns on pedestal mounts.[20][21] Records indicate that it was never armed.[19] The shifting sands caused problems for the fort and it was abandoned in the late 1920s.

20th century

editIn 1938, Gardiners Point Island was declared a National Wildlife Refuge by Franklin D. Roosevelt and transferred to the Agriculture Department.[citation needed] During World War II, the former Fort Tyler was used for target practice and was reduced to its present state of ruin. The state of New York briefly considered turning it into a park, but it is deemed a navigational hazard because of the possibilities of unexploded ordnance. It is privately owned now.[citation needed]

A manor house built by David Gardiner in 1774 burned to the ground in 1947, it is thought after a guest fell asleep while smoking. Valuable antiques were destroyed, with the caretaker escaping by jumping from a window. Owing to the high cost of upkeep, the island was put up for sale in 1937. It was bought by a multimillionaire relative, Sarah Diodati Gardiner, for $400,000. She erected a new 28-room manor house in the Georgian style. She died in 1953, unmarried, at age 90. Upon her death in 1953, the island passed in trust to her nephew Robert David Lion Gardiner and niece Alexandra Gardiner Creel (brother and sister).[5]

From 1955 until 1963, Sperry Rand leased the island for top echelon meetings.[22]

Robert David Lion Gardiner and Alexandra Gardiner Creel occupied the island at the expiration of Sperry Rand's lease in 1963. Gardiner inherited three Gardiner fortunes: from his father, his uncle and his Aunt Sarah.[11]

The island was designated as a National Natural Landmark (NNL) in April 1967 by the National Park Service, in recognition of its waterfowl and shorebird habitat, and its role as a breeding ground for osprey.[23]

Bickering ownership

editSarah Diodati Gardiner had also set aside a trust fund for upkeep of the island, but it was exhausted by the 1970s. When Alexandra Gardiner Creel died, her rights passed to her daughter, Alexandra Creel Goelet. Robert David Lion Gardiner and Goelet were to have a highly publicized dispute over ownership and direction of the island.

Robert accused Alexandra of wanting to sell and develop the island. She accused him of not paying his share of the estimated $2 million per year upkeep and taxes of the island. Robert said he would not oppose ownership by the government or a private conservancy group.[5] The case went to court in 1980 and Robert was initially barred from visiting the island, but in 1992, courts ruled that he could visit the island (although the Goelets and Gardiner were not on the island at the same time).

Robert Gardiner, who claimed the notional title "16th Lord of the Manor of Gardiner's Island" and lived in East Hampton, married in 1961 but had no children, leaving him with no direct heir. In 1989, Gardiner attempted unsuccessfully to adopt a middle-aged Mississippi businessman, George Gardiner Green Jr., as his son.[5] Green was a descendant of Lion Gardiner. Upon Robert's death in 2004, total ownership passed to Goelet. Shortly before his death he said:

We have always married into wealth. We've covered all our bets. We were on both sides of the Revolution, and both sides of the Civil War. The Gardiner family always came out on top.[5]

21st century

editIn 2005, the Goelets offered to place a conservation easement on the island in exchange for a promise from the Town of East Hampton not to rezone the land, change its assessment or attempt to acquire it by condemnation. The Goelets and East Hampton agreed upon the easement through 2025.[24]

Gardiners Island's NNL status was removed in July 2006, following a request from the island's owner, Alexandra Creel Goelet.[25]

Ownership

edit- Poggatacut (sachem) and Aswaw, his wife, deeded Manchonat to Lion Gardiner. He was succeeded by Wyandanch as Grand Sachem.

- Lion Gardiner as a proprietary colony,[citation needed][how?] 1st Proprietor and Lord of the Manor, 1639–63[26]

- David Gardiner[11]

- John Gardiner[11]

- David Gardiner[11]

- John Lyon Gardiner I[11]

- Joseph Gardiner jr 1992 [11]

- David Johnson Gardiner, 1825–29[11]

- John Gardiner, 1829–61[11]

- Samuel Buell Gardiner, 1861–82[11]

- John Lyon Gardiner II, 1882–1910[11][27]

- Lion Gardiner, 1910–?[11]

- Joseph Gardiner sr 1969–

- Joseph Gardiner[11]

- Sarah Diodati Gardiner 1937–53[26]

- Alexandra Gardiner Creel and Robert David Lion Gardiner, 1953–2004[26]

- Alexandra Creel Goelet, 2004—

Notable people

edit- Lewis A. Edwards (1811–1879), was an American businessman, manufacturer, politician and a Democratic member of the New York State Senate (1st D.)[28]

- Julia Gardiner Tyler, former First Lady of the United States; wife of U.S. President John Tyler (1844–1845)

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ Weigold, Mary E. (2015). Peconic Bay: Four Centuries of History on Long Island's North and South Forks. Syracuse University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780815653097.

- ^ Nevius, Michelle & Nevius, James (2009), Inside the Apple: A Streetwise History of New York City, New York: Free Press, ISBN 141658997X, pp. 84-85

- ^ Trebay, Guy (2004-08-29). "The Last Lord Of Gardiners Island". The New York Times.

- ^ "1999 Land Available for Development — Eastern Suffolk County" (PDF). co.suffolk.ny.us. Suffolk County Department of Planning. October 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 18, 2006. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

- ^ a b c d e Wick, Steve. "Gardiners Island: What Next?". Newsday. Archived from the original on June 16, 2004.

- ^ Gardiner's Island: A Visit with Robert David Lion Gardiner (1976), retrieved 2021-05-16

- ^ "Robert Gardiner Dies". Washington Post. 25 Aug 2004. Retrieved 16 Mar 2021.

- ^ a b Gardiner, Curtiss Crane (1890). Lion Gardiner, and his descendants ... [1599-1890]. St. Louis : A. Whipple.

- ^ "Another Isle of Wight". Round-the-island.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2008-07-05. Retrieved 2020-12-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) Referencing Newsday. - ^ Hedges, Henry P. (1849). "Chapter 6". History of East Hampton – via longislandgenealogy.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Grant, Ellsworth S. (October 1975). "To The Manor Born". American Heritage. 26 (6). Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Captain William Kidd's cloth of gold". OCLC.org. The Long Island Collection, East Hampton Library. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "A verbatim report of John Gardiner's testimony taken before a board of government commissioners at Boston". New England Historical and Genealogy Register. VI: 72–84.

- ^ Edwards Rattray, Jeannette (1953). "Pirates and Prohibition". East Hampton History. Garden City, New York: Country Life Press. Retrieved January 12, 2007 – via longislandgeneology.com.

- ^ Zacks, Richard. The Pirate Hunter: The True Story of Captain Kidd. pp. 153–59, 241, 260.

- ^ "History". East Hampton Star – via easthamptonstar.com. [permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Stevens, John Austin (January 1885). "The Manor of Gardiners Island". The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. p. 12 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Gardiners Island Lighthouses". East End Lighthouses. Archived from the original on 2012-01-29. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ^ a b "Fort Tyler". FortWiki.com.

- ^ Berhow, Mark A., ed. (2015). American Seacoast Defenses (Third ed.). McLean, Virginia: CDSG Press. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-9748167-3-9.

- ^ "Fort Tyler". dmna.ny.gov. New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center, NYS Division of Military and Naval Affairs. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Gardiners Is One Family Island". Reading Eagle. Associated Press. August 1, 1976. pp. 8, 10. Retrieved December 23, 2020 – via Google News Archive.

- ^ National Registry of Natural Landmarks. National Park Service. 1989. p. 79. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ Freedman, Mitchell (May 24, 2005). "Town strikes deal to preserve island". Newsday.

- ^ "Notice of Multiple National Natural Landmark Boundary Changes and De-designations" (PDF). Federal Register. 71 (138): 41050. July 19, 2006. Retrieved November 20, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Robert D.L. Gardiner, 93, Lord of His Own Island, Dies". The New York Times. August 24, 2004. Retrieved January 29, 2014.

Robert David Lion Gardiner, the last heir to bear the name of the family that has owned Gardiner's Island ... Mr. Gardiner called himself the 16th Lord of the Manor

- ^ "John Lyon Gardiner Dead. Owner of Gardiner's Island, Associated with Capt. Kidd, the Pirate" (PDF). The New York Times. January 22, 1910. Retrieved 2014-01-29.

- ^ The New York Civil List compiled by Franklin Benjamin Hough, Stephen C. Hutchins and Edgar Albert Werner (1870; pg. 444 and 591)

External links

edit- "Gardiners Island". Encyclopedia of New York. Syracuse University.