José Manuel Emiliano Balmaceda Fernández (Latin American Spanish: [maˈnwel βalmaˈseða]; July 19, 1840 – September 19, 1891) served as the 10th President of Chile from September 18, 1886, to August 29, 1891. Balmaceda was part of the Castilian-Basque aristocracy in Chile.[1] While he was president, his political disagreements with the Chilean congress led to the 1891 Chilean Civil War, following which he shot and killed himself.

José Manuel Balmaceda | |

|---|---|

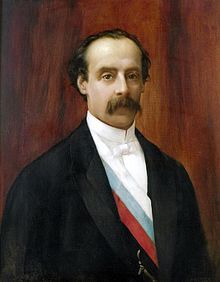

Portrait by Fernando Laroche, 1891 | |

| 10th President of Chile | |

| In office September 18, 1886 – August 29, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Domingo Santa María |

| Succeeded by | Manuel Baquedano |

| Personal details | |

| Born | July 19, 1840 Hacienda Bucalemu, Chile |

| Died | September 19, 1891 (aged 51) Santiago, Chile |

| Political party | Liberal |

| Spouse | Emilia de Toro Herrera |

| Signature | |

Early life

editBalmaceda was born in Bucalemu, the eldest of the 12 children of Manuel José Balmaceda Ballesteros and Encarnación Fernández Salas.[2] His parents were wealthy, and in his early days he was chiefly concerned in industrial and agricultural enterprises.[3] In 1849, he attended the School of the French Friars, and considered joining the clergy, studying several years of theology at the Santiago Seminary.[2]

In 1864 he became secretary to Manuel Montt,[4] who was one of the representatives of the Chilean government at the general South American congress at Lima, and after his return obtained great distinction as an orator in the national assembly.[3] In 1868 he joined forces with Justo and Domingo Arteaga Alemparte to found and publish the newspaper "La Libertad" (Freedom). He also was a constant contributor to the "Revista de Santiago", and published two monographs: "The political solution in electoral freedom" and "Church and State". In 1869 he joined the Club de la Reforma, which became the political basis of the Liberal Party. The essential tenets of the political program were freedom of religion, increased personal and political freedom, elimination of governmental intervention in the electoral process, reform of the 1833 constitution and restriction of the powers of the President.[2]

On the basis of this radical program, he was elected Deputy for Carelmapu several times: 1864–1867; 1870–1873; 1873–1876; 1876–1879; 1879–1882. Under President Aníbal Pinto,[2] he discharged some diplomatic missions abroad,[3] and is credited with persuading Argentina not to join the War of the Pacific in 1878.[2] In 1882 he was re-elected both for Carelmapu and Santiago.[citation needed] He decided to accept neither and became instead successively Minister of Foreign Affairs and Colonization and of the Interior under the presidency of Domingo Santa María.[2] In the latter capacity he carried compulsory civil marriage and several other laws highly obnoxious to the conservatives and the clergy.[3] Balmaceda was also elected a Senator for Coquimbo (1882–1888).[citation needed] He was proclaimed a candidate to the presidency on the Odeon Theater of Valparaíso on January 17, 1886, with the support of the Nacional, Liberal and part of the Radical Parties. On June 25 he was elected president as sole candidate.[2]

Presidency

editby Nicolás Guzmán Bustamante

Balmaceda became President of Chile in 1886.[3] His election was bitterly opposed by the Conservatives and dissident Liberals, but was finally achieved by the official influence of President Domingo Santa María. On assuming office President Balmaceda endeavoured to bring about a reconciliation of all sections of the Liberal Party in Congress and so form a solid majority to support the administration, and to this end he nominated representatives of the different political groups as ministers. Six months later the cabinet was reorganized, and two of the most bitter opponents of his election were accorded portfolios. But despite his great capacity, Balmaceda's imperious temper little fitted him for the post.[5]

Balmaceda instituted wide-reaching reforms, believing that he had now secured the support of the majority in Congress for any measures he decided to put forward. The new president initiated an unparalleled policy of heavy expenditure on public works, school building, and the strengthening of the naval and military forces of the republic. Contracts were given out to the value of £6,000,000 for the construction of railways in the southern districts; some $10,000,000 were expended in the erection of schools and colleges; three cruisers and two seagoing torpedo boats were added to the Navy; the construction of the naval port at Talcahuano was actively pushed forward; new armament was purchased for the infantry and artillery branches of the Army, and heavy guns were acquired for permanently and strongly fortifying the ports of Valparaíso, Talcahuano, and Iquique.[5]

In itself this policy was not unreasonable, and in many ways extremely beneficial for the country. Unfortunately corruption crept into the expenditure of the large sums involved. Contracts were given by favour and not by merit, and the progress made in the construction of the new public works was far from satisfactory. The opposition in Congress to President Balmaceda began to increase rapidly towards the close of 1887, and further gained ground in 1888. In order to ensure a majority favourable to his views, the President threw the whole weight of his official influence into the elections for Senators and Deputies in 1888; but many of the members returned to the chambers through this official influence joined the opposition shortly after taking their seats.[5]

Conflict with Congress

editIn 1889 Congress became distinctly hostile to the administration of President Balmaceda, and the political situation became grave, and at times threatened to involve the country in civil war. According to usage and custom in Chile at the time, a ministry (the set of ministers) did not remain in office unless supported by a majority in the chambers. Balmaceda now found himself in the impossible position of being unable to appoint ministers that would be supported by a majority in the Senate and Chamber of Deputies and at the same time be in accordance with his policies. At this juncture the President assumed that the constitution gave him the power of nominating and maintaining in office any ministers he might consider fitting persons for the purpose, and that Congress had no right of interference in the matter.[5]

The chambers were now only waiting for a suitable opportunity to assert their authority. In 1890 it was stated that President Balmaceda had determined to nominate and cause to be elected as his successor in 1891 one of his own personal friends. This question of the election of another President brought matters to a head, and Congress refused to vote any funds to carry on the government. To avoid trouble Balmaceda entered into a compromise with Congress, and agreed to nominate a ministry to their liking on condition that the supplies for 1890 were voted. This cabinet, however, was of short duration, and resigned when the ministers understood the full amount of friction between the President and Congress. Balmaceda then nominated a ministry not in accord with the views of Congress, under Claudio Vicuña, whom it was no secret that Balmaceda intended to be his successor in the presidential chair. To prevent any expression of opinion upon his conduct in the matter, he refrained from summoning an extraordinary session of the legislature for discussion of the estimates of revenue and expenditure for 1891.[5]

Civil war

editWhen January 1, 1891 arrived, the president published a decree in the Diario Oficial to the effect that the budget of 1890 would be considered the official budget for 1891. This act was illegal and exceeded the authority of executive power. In response to the action of President Balmaceda, the vice-president of the Senate, Waldo Silva, and the president of the Chamber of Deputies, Ramón Barros Luco, issued a proclamation appointing Captain Jorge Montt as commander of the Navy, and stating that the Navy could not recognize the authority of Balmaceda so long as he did not administer public affairs in accordance with the constitutional law of Chile. The majority of the members of the chambers sided with this movement, and signed an Act of Deposition of President Balmaceda. On 7 January Waldo Silva, Barros Luco, and a number of senators and deputies embarked on the Chilean warship "Blanco Encalada," accompanied by the "Esmeralda" and "O'Higgins" and other vessels, and sailed out of Valparaiso harbor and proceeded northwards to Tarapacá to organize armed resistance against the president, launching the civil war.[5]

This act in defiance of Congress was not the only issue that brought about the revolution. Balmaceda had alienated the aristocratic classes of Chile with his personal vanity and ambition and soon after his election was irreconcilably at odds with the majority of the national representatives. The oligarchy composed of the great landowners had always been an important factor in the political life of the republic; when President Balmaceda found himself outside this circle he endeavored to govern without their support, and to bring into the administration a group of people outside the inner circles of political power, whom he could easily control. Clerical influence also turned against him as a result of his radically secular ideas about government.[5]

On 23 May 1891, London Times correspondent in Chile Maurice Hervey alleged British intervention as having been key to the overthrow of Balmaceda, writing, "Beyond the possibility of contradiction, the instigators, the wire-pullers, the financial supporters of the so called revolution were and are the English or Anglo Chilean owners of the nitrate deposits of the Tarapacá."[6]

Aftermath

editAfter Balmaceda's forces were overwhelmed and destroyed in the Battle of La Placilla, it was clear that he could no longer hope to find a sufficient strength amongst his adherents to maintain himself in power, and in view of the rapid approach of the rebel army, he abandoned his official duties to seek an asylum in the Argentine legation.[5] On August 29, he officially handed power to General Manuel Baquedano, who maintained order in Santiago until the arrival of the congressional leaders on August 30.[citation needed]

The president remained concealed in the Argentine legation until September 19. On the morning of that date, one day after the anniversary of his elevation to the presidency and when the term for which he had been elected president of the republic terminated, he shot and killed himself, rather than surrender to the new government.[5][7] His reason for this act, put forward in letters written shortly before his end, was that he did not believe the conquerors would give him an impartial trial. The death of Balmaceda finished all cause of contention in Chile, and was the closing act of the most severe and bloodiest struggle that the country had ever witnessed.[citation needed]

Family

editOn 11 October 1865,[8] Balmaceda married Emilia de Toro Herrera, granddaughter of Mateo de Toro Zambrano, 1st Count of La Conquista, and together they had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood:[4][9]

- María Emilia del Carmen (born 14 July 1866)

- Domingo Nicolás (born 14 September 1870)

- Pedro Alberto José (23 April 1868–1889), poet and writer, died age 21[9]

- María Elisa (born 24 March 1873), married Emilio Bello Codesido

- Julia (born 10 May 1874)

- María Catalina (6 November 1875–1967)

- Enrique Víctor Aquiles (3 March 1878 – 4 January 1962), Chilean diplomat

- José Manuel (born 13 March 1882)

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "Historia de Chile". 26 June 2003. [verification needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g BCN staff.

- ^ a b c d e Chisholm 1911a, p. 284.

- ^ a b Visión y Verdad Sobre Balmaceda (PDF) (in Spanish). Fundación Presidente Balmaceda. p. 60. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Chisholm 1911, p. 156.

- ^ Zeitlin 2014, p. 93.

- ^ Collier & Sater 2004, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Marriage of Emilia Toro Herrera and Jose Manuel Balmaceda Fernandez; Chile, Select Marriages, 1579–1930

- ^ a b Ramírez Morales, Fernando. Breve Esbozo de la Familia del Presidente Jose Manuel Balmaceda Y Sus Relaciones Afines (1850–1925) (PDF) (in Spanish). p. 199. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

References

edit- BCN staff. "Parliamentary Artist Profile José Manuel Balmaceda Fernández" (in Spanish). Library of National Congress of Chile (BCN). Archived from the original on 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2016-09-06. (published under the Creative Commons Atribución 3.0 Chile )

- Collier, Simon; Sater, William F. (2004) [1996]. "Santa Maria and Balmaceda Studies". A History of Chile, 1808–2002. Cambridge Latin American (Second ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-0-521-53484-0.

- Zeitlin, Maurice (2014) [1988]. The Civil Wars in Chile: (or The Bourgeois Revolutions that Never Were). Princeton University Press.

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911a). "Balmaceda, José Manuel". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 284.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Chile". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 153–160.