Mahamat-Saleh Haroun (French pronunciation: [ma.ama sale aʁun]; Arabic: محمد الصالح هارون) was born in 1961 in Abéché, Chad. He is a film director from Chad. He left Chad during the civil wars of the 1980s. Haroun is the first Chadian full-length film director. He both writes and directs his films. Though he has lived in France since 1982, most of his films have been set in and made in Chad.

Mahamat-Saleh Haroun | |

|---|---|

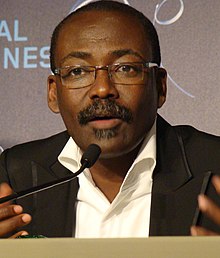

Haroun at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival | |

| Born | 1961 (age 62–63) N'Djamena, Chad |

| Occupation | Film director |

| Awards | 1999: Best first film award at the Venice Film Festival for Bye Bye Africa |

Biography

editMahamat-Saleh Haroun studied film at the Conservatoire Libre du Cinéma in Paris. He later went to study journalism at Bordeaux I.U.T (Technical Institute), and then worked for several years as a journalist in France. He directed his first short film Tan Koul in 1991, but he became famous after his second film Maral Tanié (25 minutes), directed in 1994. This film tells the story of seventeen-year-old Halimé, whose family forces her to marry a man in his fifties. Halimé refuses to consummate the marriage.

In 1999, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun released his first feature film Bye Bye Africa[1], which he wrote, directed, and starred in. The film, a docu-drama, tells the story of a film director from Chad who returns to his home country. It received a jury mention at the Venice Film Festival. Bye Bye Africa is the first feature film from Chad.

In 2001, he directed a short film Letter from New York City,[2] which won the Prize for the best video at the 11th African Film Festival in Milan.

In 2002, he wrote and directed his second feature film, Abouna[3] which won the best cinematography award at FESPACO in 2003. Set in the capital of Chad, N'Djamena, Abouna is the story of two young brothers (Amine and Tahir) who wake up one morning and realise that their father has left the family. The boys decide to search for their father in the city. While watching a movie in the cinema, they think they recognize their father as one of the actors. They try to steal the film to examine it but they are caught by the police. Unsure of how to deal with them and becoming mentally exhausted herself, their mother sends them away to a Koranic school. Here they hatch a plan to escape and find their father - that is until Tahir meets a mute girl at the school.

The filmmaker then shot a documentary, Kalala[4], the intimate portrait of Hissein Djibrine (nicknamed Kalala), a close friend of Haroun who died in 2003 of AIDS. Hissein Djibrine produced the filmmaker's first two feature films, and Haroun was deeply touched by his death and wanted to honor his memory.

In 2006, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun directed Dry Season (Daratt),[5] the story of young Akim, who at the age of 16, left his village in Chad for the capital, N’Djamena, to avenge his father. He quickly finds the murderer, a former war criminal and gets hired as an apprentice in his bakery. But with this man Akim experiences feelings that he never had before. This film won the bronze standard of Yennenga, as well as the best cinematography award at FESPACO in 2007.

In 2008, he directed Sex, Okra and Salted Butter[6] (Sexe, gombo et beurre salé). This comedy follows the lives of a family of Chadian immigrants in Bordeaux, France. Hortense cheats on her much older husband, her husband also strays, and their son goes to great lengths to conceal his sexuality from his parents. Meanwhile, the two younger sons are looking for guidance outside the family.

In 2010, he directed his fourth feature film A Screaming Man[7] which won the Jury Prize at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival. This film tells the story of Adam and his son Abdel who are separated by the civil war in Chad. The father's job is in jeopardy because the new management of the hotel wants to give his job to his son. The presence of rebels in N’Djamena pushes Adam to lose any way to contact his son. Haroun received the Robert Bresson Prize for this film at the Venice Film Festival.

In 2011, he was a member of the jury for the main competition chaired by Robert De Niro at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival.

In 2012, he was selected as a president of the 28th International Love Film Festival at Mons.

In 2013, his film Grigris[8] was nominated for the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival. Set in Chad, the film tells the story of Grisgris, a young man who is disabled, dreams of becoming a dancer and gets involved in smuggling. With Grisgris, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun endeavors to show the youth of a country in full reconstruction.

In 2016, Haroun was again at Cannes to present his documentary Hissein Habré, a Chadian Tragedy,[9] about the Chadian dictator from 1982 to 1990, Hissein Habré. The film consists of interviews (mostly conducted by Clément Abaifouta of the Association of the Victims of the Hissein Habré Regime) of victims of Habré about their arrests and tortures by the secret police.

In 2017 Haroun made his second feature film set in France, A Season in France.[10] This film is about Abbas, a French teacher in the Central African Republic who fled with his family during the civil war. The memory of his wife who was killed during their journey still haunts him. When he returns to France, he falls in love with Carole, a woman who helps him and his two sons. Unable to obtain refugee status, Abbas and his brother are given a notice of deportation and a hard choice to make.

In Haroun's 2020 film Lingui,[11] he returns to Chad, focusing on the problems faced by thirty-year-old Amina and her daughter Maria, who is half her age. When Amina, a practicing Muslim, realizes that her daughter is pregnant and that she wants to have an abortion, the mother and daughter are confronted by the fact that abortion is both illegal and “immoral” in Chad.

Politics

editMahamat-Saleh Haroun was Minister of Tourism, Culture and Crafts of Chad from February 5, 2017, to February 8, 2018.

In December 2023, alongside 50 other filmmakers, Mahamat-Saleh Haroun signed an open letter published in Libération demanding a ceasefire and an end to the killing of civilians amid the 2023 Israeli invasion of the Gaza Strip, and for a humanitarian corridor into Gaza to be established for humanitarian aid, and the release of hostages.[12][13][14]

Novel

editHaroun's first novel, Djibril ou les Ombres portées, was published in 2017 by Gallimard.

Filmography

editShorts

edit- Maral Tanie (1994)

- Goi-Goi (1995)

- B 400 (1997)

- Letter from New York City (2001)

Feature films

edit- Bye Bye Africa (1999)

- Abouna (2002)

- Daratt (2006)

- Sex, Okra and Salted Butter (2008)

- A Screaming Man (2010)

- GriGris (2013)

- A Season in France (2017)

- Lingui, The Sacred Bonds (2021)

Documentaries

edit- Bord' Africa (1995)

- Sotigui Kouyate, a modern griot (1997)

- Kalala (2005)

- Hissane Habré: A Chadian Tragedy (2016)

Distinctions

editAwards

- 1999: Best first film award at the Venice Film Festival for Bye Bye Africa

- 2006: Special Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival for Daratt.

- 2007: Yennenga bronze stallion and Best Photo Award at FESPACO 2007 for Daratt.

- 2010: Jury Prize at the Cannes Festival 2010 for A Screaming Man.

- 2010: Robert-Bresson Prize at the Venice Film Festival (awarded by the Catholic Church) for A Screaming Man.

References

edit- ^ "Bye Bye Africa", Wikipedia, 2020-04-03, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ "Letter from New York City | IFFR". iffr.com. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "List of FESPACO award winners", Wikipedia, 2021-03-11, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ "Kalala (2006)". BFI. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "Daratt", Wikipedia, 2020-04-21, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ "Sex, Okra and Salted Butter", Wikipedia, 2020-11-09, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ "A Screaming Man", Wikipedia, 2021-01-31, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ "GriGris", Wikipedia, 2020-04-30, retrieved 2021-04-03

- ^ Kenigsberg, Ben (2017-09-19). "Review: 'Hissein Habré, a Chadian Tragedy' Shows the Victims of a Dictator". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "A Season in France". Time Out Worldwide. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "Lingui". Cineuropa - the best of european cinema. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- ^ "Gaza : des cinéastes du monde entier demandent un cessez-le-feu immédiat". Libération (in French). 28 December 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ Newman, Nick (29 December 2023). "Claire Denis, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Christian Petzold, Apichatpong Weerasethakul & More Sign Demand for Ceasefire in Gaza". The Film Stage. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- ^ "Directors of cinema sign petition for immediate ceasefire". The Jerusalem Post. 31 December 2023. Retrieved 24 January 2024.