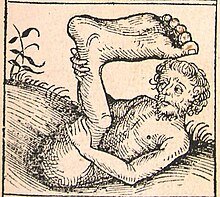

Monopods (also called sciapods, skiapods, skiapodes) were mythological dwarf-like creatures with a single, large foot extending from a leg centred in the middle of their bodies. The names monopod and skiapod (σκιάποδες) are both Greek, respectively meaning "one-foot" and "shadow-foot".

Ancient Greek and Roman literature

editMonopods appear in Aristophanes' play The Birds, first performed in 414 BC.[1] They are described by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where he reports travelers' stories from encounters or sightings of Monopods in India. Pliny remarks that they are first mentioned by Ctesias in his book Indika (India), a record of the view of Persians of India which only remains in fragments. Pliny describes Monopods like this:

He [Ctesias] speaks also of another race of men, who are known as Monocoli, who have only one leg, but are able to leap with surprising agility. The same people are also called Sciapodae, because they are in the habit of lying on their backs, during the time of the extreme heat, and protect themselves from the sun by the shade of their feet.[2]

Philostratus mentions Skiapodes in his Life of Apollonius of Tyana, which was cited by Eusebius in his Treatise Against Hierocles. Apollonius of Tyana believes the Skiapodes live in India and Ethiopia, and asks the Indian sage Iarkhas about their existence.

St. Augustine (354–430) mentions the "Skiopodes" in The City of God, Book 16, Chapter 8 entitled "Whether Certain Monstrous Races of Men Are Derived From the Stock of Adam or Noah's Sons",[3] and mentions that it is uncertain whether such creatures exist.

Medieval literature

editReference to the legend continued into the Middle Ages, for example with Isidore of Seville in his Etymologiae, where he writes:

The race of Sciopodes are said to live in Ethiopia; they have only one leg, and are wonderfully speedy. The Greeks call them σκιαπόδες ("shade-footed ones") because when it is hot they lie on their backs on the ground and are shaded by the great size of their foot.[4]

The Hereford Mappa Mundi, drawn c. 1300, shows a sciapod on one side of the world,[5] as does a world map drawn by Beatus of Liébana (c. 730 – c. 800).[6]

Einfœtingr of Canada

editA race of the "One-Legged",[7] or the "Uniped" (Old Norse: einfœtingr)[8][9] was allegedly encountered by Thorfinn Karlsefni and his group of Icelandic settlers in North America in the early 11th century, according to Eiríks saga rauða (Saga of Erik the Red).[a] The presence of "unipedes maritimi" in Greenland was marked on Claudius Clavus's map dated 1427.[11]

According to the saga, Karlsefni Thorvald Eiriksson and others assembled a search party for Thorhall, and sailed around Kjalarnes and then south. After sailing for a long time, while moored on the south side of a west-flowing river, they were shot at by a one-footed man (einfœtingr), and Thorvald died from an arrow wound.[7]

The saga goes on to relate that the party went northward and approached what they guessed to be Einfœtingaland ("Land of the One-Legged" or "Country of the Unipeds").[7][9]

Origin

editAccording to Carl A. P. Ruck, the Monopods' cited existence in India refers to the Vedic Aja Ekapad ("Not-born Single-foot"), an epithet for Soma. Since Soma is a botanical deity the single foot would represent the stem of an entheogenic plant or fungus.[12]

John of Marignolli (1338–1353) provides another explanation of these creatures. Quote from his travels from India:[13]

The truth is that no such people do exist as nations, though there may be an individual monster here and there. Nor is there any people at all such as has been invented, who have but one foot which they use to shade themselves withal. But as all the Indians commonly go naked, they are in the habit of carrying a thing like a little tent-roof on a cane handle, which they open out at will as a protection against sun or rain. This they call a chatyr; I brought one to Florence with me. And this it is which the poets have converted into a foot.

— Giovanni de' Marignolli

Fiction

editChronicles of Narnia

editC. S. Lewis features monopods in the book The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, a part of his children's series The Chronicles of Narnia.

In the story, a tribe of foolish dwarves known as Duffers inhabit a small island near the edge of the Narnian world along with a magician named Coriakin, who has transformed them into monopods as a punishment. They have become so unhappy with their appearance that they have made themselves invisible. They are (re)discovered by explorers from the Narnian ship, the Dawn Treader, which has landed on the island to rest and resupply, and at their request Lucy Pevensie makes them visible again. Through confusion between their old name, "Duffers", and their new name of "Monopods", they become known as the "Dufflepuds".[14]

According to Brian Sibley's book The Land of Narnia, Lewis may have based their appearance on drawings from the Hereford Mappa Mundi.

Baudolino

editUmberto Eco in his novel Baudolino describes a sciapod named Gavagai. The name of the creature "Gavagai" is a reference to Quine's example of indeterminacy of translation.

The Name of the Rose

editIn Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose, the abbey's chapter house is decorated with carvings of "the inhabitants of unknown worlds," including "sciopods, who run swiftly on their single leg and when they want to take shelter from the sun stretch out and hold up their great foot like an umbrella."[15]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ It was also noted by C. C. Rafn that Rímbegla (end of 12th century, published 1780) mentions a population of Unipeds (einfœtingjar) dwelling in Bláland in Aethiopia.[10]

References

edit- Citations

- ^ Aristophanes. The Birds, ln. 1554

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History VII:2

- ^ Augustine, Chapter 8. — Whether Certain Monstrous Races of Men Are Derived From the Stock of Adam or Noah's Sons

- ^ Barney, Stephen A. et al (translators) (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge University Press. p. 245. ISBN 9781139456166.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "The Hereford Mappamundi". Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ Beato del Burgo de Osma (c. 750–800). Hereford Mappa Mundi. Folios 34v-35.

- ^ a b c Kunz, Keneva (tr.) (2000). Eirik the Red's Saga (Ch. 11–12). New York: Viking. pp. 671–672. ISBN 9780670889907.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) 2005 e-text edition - ^ Steensby, H. P. (1918), "Norsemen´s Route to Wineland", Meddelelser om Grønland, 56: 194-196; entire volume (pdf)

- ^ a b Beamish, North Ludlow, ed. (1841). "Saga of Thorfinn Karlsefne". The Discovery of America by the Northmen: In the Tenth Century. London: T. and W. Boone. pp. 100–102., after C. C. Rafn's edition.

- ^ Beamish (1841), p. 100, note *, apud Rafn, Carl Christian (1837) p. 158

- ^ Steensby (1918), p. 195, note 2apud Storm, Gustav (1887) p. 317

- ^ Ruck, Carl A.P. (1981). "Mushrooms and philosophers". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 4 (2): 179–205. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(81)90034-9. PMID 7031377.

- ^ Yule, Sir Henry (1913). Cathay and the way thither: being a collection of medieval notices of China VOL. II. London: The Hakluyt Society. p. 257.

- ^ Lewis, C.S. (1965) [1952]. The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. Puffin. pp. 114–124, 139–147.

- ^ Eco, Umberto (1994) [1980]. The Name of the Rose. Harcourt Brace and Company. pp. 336–337.