The Official Irish Republican Army or Official IRA (OIRA; Irish: Óglaigh na hÉireann) was an Irish republican paramilitary group whose goal was to remove Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom and create a "workers' republic" encompassing all of Ireland.[2] It emerged in December 1969, shortly after the beginning of the Troubles, when the Irish Republican Army (IRA) split into two factions. The other was the Provisional IRA. Each continued to call itself simply "the IRA" and rejected the other's legitimacy.

| Official Irish Republican Army (Óglaigh na hÉireann) | |

|---|---|

Official IRA patrol vehicle in Turf Lodge, Belfast, April 1972 | |

| Leaders | Cathal Goulding, Billy McMillen |

| Dates of operation | December 1969 – Late 1990s (on ceasefire since 1972) |

| Split from | Anti-Treaty Irish Republican Army |

| Headquarters | Dublin |

| Active regions | Northern Ireland (mainly); Republic of Ireland; England |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-left |

| Size | 1,500–2,000 (between 1969 and 1972) |

| Allies | |

| Opponents | Provisional IRA Irish National Liberation Army |

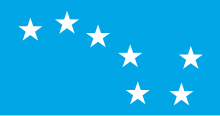

| Flag |  |

Unlike the "Provisionals", the "Officials" did not think that Ireland could be unified until the Protestant majority and Catholic minority of Northern Ireland were at peace. The Officials were Marxist-Leninists and worked to form a united front with other Irish communist groups, named the Irish National Liberation Front (NLF).[3] The Officials were called the NLF by the Provisionals[4][5] and "stickies" by nationalists in Belfast (apparently in reference to members who would glue Easter lilies to their uniforms),[6] and they were sometimes nicknamed the "Red IRA" by others.[7][8][9]

It waged a limited campaign against the British Army, mainly involving shooting and bombing attacks on troops in urban working-class neighbourhoods. Most notably, it was involved in the 1970 Falls Curfew and carried out the 1972 Aldershot bombing. In May 1972, it declared a ceasefire and vowed to limit its actions to defence and retaliation.[10] By this time, the Provisional IRA had become the larger and more active faction. Following the ceasefire, the OIRA began to be referred to as "Group B" within the Official movement.[11][12] It became involved in feuds with the Provisional IRA and the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA),[13] an OIRA splinter group formed in 1974. It has also been involved in organized crime and vigilantism.

The Official IRA was linked to the political party Official Sinn Féin, later renamed Sinn Féin The Workers Party and then the Workers' Party.

Split in the Republican movement, 1969–1970

editShift to the left

editThe split in the Irish Republican Army, soon followed by a parallel split in Sinn Féin, was the result of the dissatisfaction of more traditional and militant republicans at the political direction taken by the leadership. The particular object of their discontent was Sinn Féin's ending of its policy of abstentionism in the Republic of Ireland. This issue is a key one in republican ideology, as traditional republicans regarded the Irish state as illegitimate and maintained that their loyalty was due only to the Irish Republic declared in 1916 and in their view, represented by the IRA Army Council.[14]

During the 1960s, the republican movement under the leadership of Cathal Goulding radically re-assessed their ideology and tactics after the dismal failure of the IRA's Border Campaign in the years 1956–62. They were heavily influenced by popular front ideology and drew close to communist thinking. A key intermediary body was the Communist Party of Great Britain's organisation for Irish exiles, the Connolly Association. The Marxist analysis was that the conflict in Northern Ireland was a "bourgeois nationalist" one between the Ulster Protestant and Irish Catholic working classes, fomented and continued by the ruling class. Its effect was to depress wages, since worker could be set against worker. They concluded that the first step on the road to a 32-county socialist republic in Ireland was the "democratisation" of Northern Ireland (i.e., the removal of discrimination against Catholics) and radicalisation of the southern working class. This would allow "class politics" to develop, eventually resulting in a challenge to the hegemony of both what they termed "British imperialism" and the respective unionist and Irish nationalist establishments north and south of the Irish border.[15]

Goulding and those close to him argued that, in the context of sectarian division in Northern Ireland, a military campaign against the British presence would be counter-productive, since it would delay the day when the workers would unite to address social and economic issues.

The sense that the IRA seemed to be drifting away from its conventional republican roots into Marxism angered more traditional republicans. The radicals viewed Ulster Protestants with unionist views as "fellow Irishmen deluded by bourgeois loyalties, who needed to be engaged in dialectical debate".[citation needed] As a result, they were reluctant to use force to defend Catholic areas of Belfast when they came under attack from Ulster loyalists—a role the IRA had performed since the 1920s.[16] Since the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association marches began in 1968, there had been many cases of street violence. The Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) had been shown on television in undisciplined baton charges, and had already killed five non-combatant civilians, three of whom were children. The Orange Order's "marching season" during the summer of 1969 had been characterised by violence on both sides, which culminated in the three-day "Battle of the Bogside" in Derry.

August 1969 riots

editThe critical moment came in August 1969 when there was a major outbreak of intercommunal violence in Belfast and Derry, with eight deaths, six of them Catholics, and whole streets ablaze. On 14–15 August loyalists burned out several Catholic streets in Belfast in the Northern Ireland riots of August 1969. IRA units offered resistance, however very few weapons were available for the defence of Catholic areas. Many local IRA figures, and ex-IRA members such as Joe Cahill and Billy McKee, were incensed by what they saw as the leadership's decision not to take sides and in September, they announced that they would no longer be taking orders from the Goulding leadership.[17]

Discontent was not confined to the northern IRA units. In the south also, such figures as Ruairí Ó Brádaigh and Sean MacStiofain opposed both the leadership's proposed recognition of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This increasing political divergence led to a formal split at the 1969 IRA Convention, held in December. when a group led by Ó Brádaigh and MacStiofán walked out. The split resulted from a vote at the first IRA Convention where a two-thirds majority voted that republicans should take their seats if elected to the British, Republic of Ireland or Northern Ireland Parliaments. At a second convention, a group consisting of Mac Stiofáin, Dáithí Ó Conaill, Ó Brádaigh, Joe Cahill, Paddy Mulcahy, Leo Martin, and Sean Tracey, were elected as the "Provisional" Army Council. Their supporters included Seamus Twomey.

Accounts at that time suggest that the IRA members split roughly in half, with those loyal to the Goulding-led "Official" IRA prominent in some areas while the Provisional IRA were prominent in others.[18] A strong area for the Official IRA in Belfast was the Lower Falls and Markets district, which were under the command of Billy McMillen. Other OIRA units were located in Derry, Newry, Strabane, Dublin, Wicklow and other parts of Belfast. However, the Provisionals would rapidly become the dominant faction, both as a result of intensive recruitment in response to the sectarian violence and because some Official IRA units (such as the Strabane company) later defected to them.[19]

There was a similar ideological split in Sinn Féin after a contentious 1970 Sinn Féin Ard Fheis. The leadership of Sinn Féin passed a motion to recognise the Parliaments in London, Dublin and Stormont but failed to attain the prerequisite two-thirds majority necessary to change Sinn Féin's constitutional opposition to partitionist assemblies. Those defeated in the motion walked out.[20] This resulted in a split into two groups with the Sinn Féin name. Those supportive of Seán Mac Stiofáin's "Provisional Army Council", were referred to in the media as Provisional Sinn Féin,[21][22] or Sinn Féin Kevin Street, and contested elections as Sinn Féin. The other group, under the leadership of Tomás Mac Giolla, was to contest elections first as Official Sinn Féín, then Sinn Féin The Workers' Party, and aligned itself with the Official IRA, as the Marxist faction had come to be known. The party retained the historic Sinn Féin headquarters of Gardiner Street, thus giving legitimacy to its claim, in the eyes of some,[who?] to be the legitimate successor of that party. It was briefly known popularly as Sinn Féin Gardiner Place.

The Officials were known as the "Stickies" because they sold stick-on lilies to commemorate the Easter Rising. The Provisionals, by contrast, were known as "Pinnies" (pejoratively "Pinheads") because they produced pinned-on lilies. The term "Stickies" persisted for the Officials, although Pinnies (and Pinheads) disappeared, in favour of the nickname "Provos" and for a time, "Provies" for the Provisional IRA. (The paper-and-pin Easter Lily of the IRA was the traditional commemorative badge of the Easter Rising,[23] whereas the self-adhesive Easter Lily of the Officials was a novel invention, symbolic of the divergence of opinion between them).

Impact of the split

editInitially there was much confusion among republicans on the ground; Martin McGuinness for example, joined the Official IRA in 1970, unaware that there had been a split and only later joined the Provisionals. The Provisionals eventually extended their armed campaign from defence of Catholic areas. Despite the reluctance of Cathal Goulding and the OIRA leadership, their volunteers on the ground were inevitably drawn into the violence. The Official IRA's first major confrontation with the British Army came in the Falls Curfew of July 1970, when over 3,000 British soldiers raided the Lower Falls area for arms, leading to three days of gun battles. The Official IRA lost a large amount of weaponry, and their members on the ground blamed the Provisionals for starting the firing and then leaving them alone to face the British. The bad feeling left by this and other incidents led to a feud between the two IRAs in 1970, with several shootings carried out by either side. The two IRA factions arranged a truce between them after the OIRA killing of Provisional activist, and Belfast brigade D-Company commander, Charlie Hughes (a cousin of the well-known Provisional Brendan Hughes).[citation needed]

Soviet defector Vasili Mitrokhin alleged in the 1990s that the Goulding leadership sought, in 1969, a small quantity of arms (roughly 70 rifles, along with some hand guns and explosives) from the KGB. The request was approved and the weapons reportedly arrived in Ireland in 1972,[24] although this has not been independently verified. On the whole, the OIRA had a more restricted level of activity than the Provisionals. Unlike the Provisionals, it did not establish de facto control over large Catholic areas of Belfast and Derry and its use of force was more defensive. However it retained a strong presence in certain localities, notably the Lower Falls Road, Andersonstown, Turf Lodge and the Markets areas of Belfast, along with a strong presence in Derry (particularly Free Derry in the Bogside area) as well as Newry and South County Down.[25]

Paramilitary campaign

editWhile the OIRA occasionally fought the British Army and the RUC throughout 1970 (as well as the Provisional IRA during a 1970 feud), they did not have a strong paramilitary presence until early 1971. In August 1971, after the introduction of internment without trial, OIRA units fought numerous gun battles with British troops who were deployed to arrest suspected republicans.[citation needed] The Official IRA company in the Markets area of Belfast, led by Joe McCann, held off an incursion into the area by over 600 British troops.[26] In December 1971, the Official IRA killed Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) Senator John Barnhill at his home in Strabane.[27] This was the first murder of a politician in Northern Ireland or the Republic of Ireland since the assassination of Free State Minister for Justice Kevin O'Higgins in 1927. In February 1972, the organisation also made an attempt on the life of UUP politician John Taylor.[28]

On Bloody Sunday (30 January 1972), an OIRA man in Derry is believed by the Saville Inquiry to have fired a shot with a revolver at British troops, after they had shot dead 13 civil rights demonstrators – the only republican shots fired on the day and contrary to his orders.[29] The anger caused by Bloody Sunday among Irish people was such that the Official IRA announced that it would launch an "offensive" against British forces.[citation needed]

However, the OIRA declared a ceasefire later in the same year.[30] The ceasefire, on 30 May,[30] followed a number of armed actions which had been politically damaging. The organisation bombed the Aldershot headquarters of the Parachute Regiment (the main perpetrators of Bloody Sunday), but killed only six civilians and a Roman Catholic army chaplain.[citation needed] After the killing of William Best, a Catholic British soldier home on leave in Derry, the OIRA declared a ceasefire. In addition, the death of several militant OIRA figures such as Joe McCann in confrontations with British soldiers, enabled the Goulding leadership to call off their armed campaign, which it had never supported wholeheartedly.

After 1972

editAlthough formally on ceasefire (except for "defensive actions") since 1972, the Official IRA continued some attacks on British forces up until at least 1976,[31] killing seven British soldiers in what it termed "retaliatory attacks". In addition, the OIRA's weapons were used intermittently in the ongoing feud with the Provisionals. This flared up into violence on several occasions, notably in October 1975. 11 republicans on either side were killed in the feud and a nine-year-old girl was shot dead by the Provisionals when they tried to shoot her father.

In 1974, radical elements within the organisation who objected to the ceasefire, led by Seamus Costello, established the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). Another feud ensued in the first half of 1975, during which three INLA and five OIRA members were killed. The dead included prominent members of both organisations including Costello and the OIRA O/C, Billy McMillen. However, from the mid-1970s onwards, the Official republican movement became increasingly focused on achieving its aims through left-wing constitutional politics. This did not stop sporadic paramilitary activity from the OIRA, who on 8 September 1979 killed Hugh O'Halloran in a punishment beating in the Ballymurphy area of Belfast.[32][33] O' Halloran was beaten to death with a hurley stick and a pickaxe handle.[34] Two men, one of them who admitted to OIRA membership, were imprisoned for his manslaughter.[34] The OIRA lost a number of members who gradually drifted away from the ceasefire up to shortly after the 1981 Hunger Strike, many either joining the Provisional IRA or the INLA or some simply dropping out.

From 1981 on, Sinn Féin the Workers Party, renamed the Workers' Party the following year, had some success in the Republic of Ireland, but little in Northern Ireland.

Throughout the 1980s, allegations that the Official IRA remained in existence and was engaged in criminal activity appeared in the Irish press. In June 1982 the feud with the INLA flared again after OIRA member James Flynn, the alleged assassin of Seamus Costello,[35] was shot dead by the INLA in Dublin.[36] In December 1985 five men, including Anthony McDonagh, pleaded guilty to charges of conspiracy to defraud the Inland Revenue in Northern Ireland—McDonagh was described in court as an Official IRA commander.[37] In February 1992 a British Spotlight programme alleged that the Official IRA was still active and involved in widespread racketeering and armed robberies.[38]

In 1990 the OIRA and Provisional IRA came to the brink of a feud twice, following clashes in which members of the two organisations were injured. Allegedly, mediators attempting to defuse the situation said the OIRA were at fault in both incidents.[39][40]

British security forces were aware of the continued existence of the OIRA; in 1991 a senior RUC source was quoted on a BBC Spotlight programme as saying that the Worker's Party couldn't survive without funding from OIRA criminal activity and the protection the OIRA gave the party against the Provisional IRA. Despite this the Northern Ireland Office continued to receive Workers Party delegations. Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) politician Brian Feeney alleged that the OIRA weren't interfered with in working-class Nationalist areas of Belfast to keep the Provisional IRA in check.[40]

These eventually proved a considerable political embarrassment to the Workers' Party, and in 1992 the leadership proposed amendments to the party constitution which would, inter alia, effectively allow it to purge members suspected of involvement in the Official IRA. This proposal failed to obtain the required two-thirds support at the party conference that year, and as a result the leadership, including six of the party's seven members of Dáil Éireann, left to establish a new party, later named Democratic Left.

In 1995, some former Official IRA members in the Newry area launched a "re-founded" Official Republican Movement (ORM). This group was believed to have engaged in attacks on drug dealers in the Newry area in the late 1990s.[41] In 1997 violence erupted between the ORM and the IRA; two ORM members and two Sinn Féin supporters were injured in separate gun attacks.[42]

There have been allegations of criminality against former senior Official IRA figure Seán Garland, who was accused in 2005 by the United States of helping to produce and circulate counterfeit US dollars allegedly printed in North Korea.[43][44]

Timeline of attacks and actions

editDecommissioning

editIn October 2009, after a long period of inactivity, the Official IRA began talks with a view to decommissioning its stockpile of weapons,[45] and in February 2010 the Newry-based Official Republican Movement announced that it had decommissioned its weapons.[46][47] The process was confirmed to be completed by the Independent International Commission on Decommissioning on 8 February 2010, coming in the last 24 hours of the commission's existence.[48] The decommissioning was completed at the same time as that of the republican INLA and the loyalist UDA South East Antrim Brigade.[48] The step was described by British Prime Minister Gordon Brown as a "central part of moving Northern Ireland from violence to peace".[48]

In 2015, it was reported that up to 5,000 Official IRA weapons may still be hidden in secret bunkers. The weapons were supplied to the OIRA in the 1980s by the Soviet Union's KGB and North Korea. The report said that the weapons were to be used to defend Catholic areas if there was an outbreak of major sectarian conflict, and that the plan was known only to a few high-ranking members of the organisation.[49]

Support

editThe Official IRA had relations with the Soviet Union during the Troubles. One Irish diplomat in Moscow once wrote that Ireland provided the Soviets with a "convenient stick with which to beat the West."[50] Assistance from the Soviet Union first occurred in late 1972 when Yuri Andropov who was then the head of the KGB (later to become General Secretary of the Soviet Union) authorized weapons shipments. On 21 August 1972, Andropov had presented a plan known as SPLASH to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. It was entitled "Plan for the Operation of a Shipment of Weapons to the Irish Friends". Two machine guns, 70 automatic rifles, 10 Walther pistols and 41,600 cartridges were sent. The pistols were lubricated with West German oil and the packaging was taken from several countries around the world by KGB agents so that the weapons could not be traced back to the Soviet Union. The weapons were brought to Ireland using the ship known as the Reduktor.[51] Official IRA members also travelled to the Soviet Union for training. North Korea also sent arms to the Officials and taught them with assassination techniques and bomb-making skills. Throughout the 1980s, at least 5,000 weapons were supplied by Soviet and North Korean officials to the OIRA.[1][49]

In July 1973, Irish Garda discovered eight cases of 17 rifles, 29,000 rounds of ammunition and about 60 pounds of gunpowder in Dublin sent to the OIRA by Canadian citizen John Patrick Murphy.[52] While the Officials tried to gather help from supporters in America, there was little to no evidence of such a thing happening.[53]

Deaths as a result of activity

editAccording to Malcolm Sutton's Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland, part of the Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN), the OIRA was responsible for at least 50 killings during the Troubles.[54] According to the book Lost Lives (2006 edition), it was responsible for 57 killings.[55]

Of those killed by the OIRA:[56]

- 22 (≈44%) were civilians, including 4 civilian political activists

- 19 (≈38%) were members or former members of the British security forces, including:

- 15 British soldiers and 1 former soldier

- 3 RUC officers

- 8 (≈16%) were members or former members of Republican paramilitaries

- 1 was a UDA member

The CAIN database says there were 27 OIRA members killed during the conflict,[57] while Lost Lives says there were 35 killed.[55]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b "'Official' IRA hid 5,000 AK-47s in secret bunkers". Independent.ie. 31 May 2015.

- ^ Statement from Cathal Goulding, C/S of the Official IRA, in early 1972, quoted in On Our Knees by Rosita Sweetman, Pan Books, London. 1972. ISBN 0-330-23320-3. p. 146

- ^ Coogan, Tim Pat. The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal and the Search for Peace. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. p.113

- ^ Taylor, Peter. Behind the Mask: The IRA and Sinn Fein. TV Books, 1999. p.84

- ^ O'Ballance, Edgar. Terror in Ireland: The Heritage of Hate. Presidio Press, 1981. p.133

- ^ "On the streets of Belfast, they were often distinguished as the ‘Provos’ and the ‘Stickies’, because Officials would supposedly wear commemorative Easter lilies stuck onto their shirtfronts with adhesive, whereas the more dyed-in-the wool Provos wore paper lilies affixed with a pin." Chapter 4, Keefe, Patrick Redden "Say Nothing: A Tale of Murder and Mystery in Ireland", published 2018

- ^ Rekawek, Kacper. Irish Republican Terrorism and Politics: A Comparative Study of the Official and the Provisional IRA. Taylor & Francis, 2011. pp.1-2

- ^ "Obituaries: Seamus Twomey, 70, a Leader of Provisional I.R.A." Archived 19 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters. The New York Times, 14 September 1989.

- ^ "IRA itself is divided on strategy, ideology". The Toledo Blade, 11 November 1971.

- ^ Holland, Jack (1994). INLA: Deadly Divisions. Dublin: Torc. pp. 17, 26, 39. ISBN 1-898142-05-X.

- ^ Sanders, Andrew. Inside the IRA: Dissident Republicans and the War for Legitimacy. Edinburgh University Press, 2011. p.191

- ^ Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers' Party. Penguin UK, 2009. Chapter 12: Group B.

- ^ Holland, Jack (1994). INLA: Deadly Divisions. Dublin: Torc. pp. 41–54. ISBN 1-898142-05-X.

- ^ The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, ISBN 1-84488-120-2

- ^ The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, pp. 22–70, ISBN 1-84488-120-2

- ^ Holland, Jack (1994). INLA:Divisions. Dublin: Torc. pp. 8–10. ISBN 1-898142-05-X.

- ^ The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, p. 33

- ^ "The numerous faces of the I.R.A.", This Week, 29 May 1970; J. Bowyer Bell, The Secret Army, pp. 367, 377

- ^ Eamon Mallie, Patrick Bishop, Provisional IRA, p.144

- ^ Self, Identity, and Social Movements Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Sheldon Stryker, Timothy Joseph Owens, Robert William White, (2000), p333

- ^ Assassin Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, John Bowyer Bell, (1979), p118

- ^ Sinn Féin, 1905–2005: in the shadow of gunmen, Kevin Rafter, (2005), p76

- ^ The Easter Lily Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine An Phoblacht, 5 April 2007

- ^ Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive pp492 – 503

- ^ "Members of the ruling army council of The Official I.R.A. issuing a statement july 1970" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Jack Holland, Henry McDonald, Deadly Divisions, p10

- ^ Acceptable Violence?, Time Magazine, 27 December 1971

- ^ "John Taylor: Profile". BBC News. 30 January 2001. Archived from the original on 10 April 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Report of The Bloody Sunday Inquiry – Volume I – Chapter 3". Saville Bloody Sunday Inquiry. 15 June 2010.

- ^ a b "30 May 1972: Official IRA declares ceasefire". On this day. BBC Online. 30 May 1972. Archived from the original on 2 January 2008. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ Belfast News Letter, 27 August 1976.

- ^ Sutton Index of Deaths – 1979 Archived 9 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Conflict Archive on the Internet

- ^ The Lost Revolution: The Story of the Official IRA and the Workers Party, Brian Hanley and Scott Millar, p. 411

- ^ a b McKittrick, David (2004). Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Mainstream Publishing. p. 800. ISBN 978-1840185041.

- ^ A Chronology of the Conflict – 1982 Archived 6 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Conflict Archive on the INternet

- ^ Sutton Index of Deaths – 1982 Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Conflict Archive on the Internet

- ^ Derek Dunne: In Dublin Magazine, October 1987

- ^ De Baroid, Ciaran (1989). Ballymurphy and the Irish War. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-1514-3.

- ^ Sunday Tribune, 3 December 1990.

- ^ a b Sunday Tribune, 27 October 1991.

- ^ Holland, Jack; Markey, Patrick (21–27 October 1998). "North's major drug baron shot dead in Newry". Irish Echo. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ Moriarty, Gerry (17 July 1997). "Four injured as republicans feud". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ^ "Leader of Irish Workers' Party and Official Irish Republican Army Leader of Irish Workers' Party and Official Irish Republican Army Arrested in United Kingdom on U.S. Indictment Charging Trafficking in Counterfeit United States Currency" (Press release). U.S. Department of Justice. 8 October 2005. Archived from the original on 14 October 2005.

- ^ BBC US says N Korea forged dollars Archived 12 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine 13 October

- ^ McCaffrey, Barry (10 October 2009). "Official IRA starts talking to arms body". Irish News. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009.

- ^ Allison Morris (20 February 2018). "Exclusive: The inside story of how the gun was taken out of Irish politics". Irish News. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ "Statement by the Official IRA about Decommissioning". Conflict Archive on the Internet. 8 February 2010. Archived from the original on 8 July 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ a b c Three more Northern Ireland terrorist groups lay down their arms The Times Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Official IRA "doomsday" bunkers may still contain thousands of weapons" Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Belfast Telegraph. 31 May 2015.

- ^ Casey, Maurice (26 August 2015). "Northern Ireland Under Soviet Eyes". History to the Public. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ "KGB armed Official IRA, book reveals". 16 February 2011.

- ^ Andrew Sanders and F. Stuart Ross (2020). "The Canadian Dimension to the Northern Ireland Conflict". The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies. 43: 200. JSTOR 27041321.

- ^ Andrew Sanders (25 April 2011). Inside the IRA: Dissident Republicans and the War for Legitimacy. Edinburgh University Press. p. 121. ISBN 9-7807-4864-6043.

- ^ "Sutton Index of Deaths: Organisation responsible for the death". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ^ a b David McKittrick et al. Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles. Random House, 2006. pp. 1551-54

- ^ "Sutton Index of Deaths: Crosstabulations (two-way tables)". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2014. (choose "organization" and "status"/"status summary" as the variables)

- ^ "Sutton Index of Deaths: Status of the person killed". Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN). Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

Further reading

edit- "Official IRA declares ceasefire". BBC News, 30 May 1972.