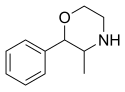

Phenmetrazine (INN, USAN, BAN) (brand name Preludin, and many others) is a stimulant drug first synthesized in 1952 and originally used as an appetite suppressant, but withdrawn from the market in the 1980s due to widespread abuse. It was initially replaced by its analogue phendimetrazine (under the brand name Prelu-2) which functions as a prodrug to phenmetrazine, but now it is rarely prescribed, due to concerns of abuse and addiction. Chemically, phenmetrazine is a substituted amphetamine containing a morpholine ring.

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Preludin, others |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, Intravenous, Vaporized, Insufflated, Suppository |

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | 8 hours |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.004.677 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C11H15NO |

| Molar mass | 177.247 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

History

editPhenmetrazine was first patented in Germany in 1952 by Boehringer-Ingelheim,[2][3] with some pharmacological data published in 1954.[4] It was the result of a search by Thomä and Wick for an anorectic drug without the side-effects of amphetamine.[5] Phenmetrazine was introduced into clinical use in 1954 in Europe.[6]

Medical use

editIn clinical use, phenmetrazine produces less nervousness, hyperexcitability, euphoria and insomnia than drugs of the amphetamine family.[7] It tends not to increase heart rate as much as other stimulants. Due to the relative lack of side effects, one study found it well tolerated in children.[5] In a study of the effectiveness on weight loss between phenmetrazine and dextroamphetamine, phenmetrazine was found to be slightly more effective.[8]

Pharmacology

editPhenmetrazine acts as a releasing agent of norepinephrine and dopamine with EC50 values of 50.4 ± 5.4 nM and 131 ± 11 nM, respectively.[9] It has negligible efficacy as a releaser of serotonin, with an EC50 value of only 7,765 ± 610 nM.[9]

After an oral dose, about 70% of the drug is excreted from the body within 24 hours. About 19% of that is excreted as the unmetabolised drug and the rest as various metabolites.[10]

In trials performed on rats, it has been found that after subcutaneous administration of phenmetrazine, both optical isomers are equally effective in reducing food intake, but in oral administration the levo isomer is more effective. In terms of central stimulation however, the dextro isomer is about 4 times as effective in both methods of administration.[11]

The salt which has been used for immediate-release formulations is phenmetrazine hydrochloride (Preludin). Sustained-release formulations were available as resin-bound, rather than soluble, salts. Both of these dosage forms share a similar bioavailability as well as time to peak onset, however, sustained-release formulations offer improved pharmacokinetics with a steady release of active ingredient which results in a lower peak concentration in blood plasma.

Synthesis

editPhenmetrazine can be synthesized in three steps from 2-bromopropiophenone and ethanolamine. The intermediate alcohol 3-methyl-2-phenylmorpholin-2-ol (1) is converted to a fumarate salt (2) with fumaric acid, then reduced with sodium borohydride to give phenmetrazine free base (3). The free base can be converted to the fumarate salt (4) by reaction with fumaric acid.[12]

Chemistry

editPhenmetrazine's structure incorporates the backbone of amphetamine, the prototypical CNS stimulant which, like phenmetrazine, is a releasing agent of dopamine and norepinephrine. The molecule also loosely resembles ethcathinone, the active metabolite of popular anorectic amfepramone (diethylpropion). Unlike phenmetrazine, ethcathinone (and therefore amfepramone as well) are mostly selective as noradrenaline releasing agents.

Recreational use

editPhenmetrazine has been used recreationally in many countries, including Sweden. When stimulant use first became prevalent in Sweden in the 1950s, phenmetrazine was preferred to amphetamine and methamphetamine by users.[13] In the autobiographical novel Rush by Kim Wozencraft, intravenous phenmetrazine is described as the most euphoric and pro-sexual of the stimulants the author used.

Phenmetrazine was classified as a narcotic in Sweden in 1959, and was taken completely off the market in 1965. At first the illegal demand was satisfied by smuggling from Germany, and later Spain and Italy. At first, Preludin tablets were smuggled, but soon the smugglers started bringing in raw phenmetrazine powder. Eventually amphetamine became the dominant stimulant of abuse because of its greater availability.

Phenmetrazine was taken by the Beatles early in their career. Paul McCartney was one known user. McCartney's introduction to drugs started in Hamburg, Germany. The Beatles had to play for hours, and they were often given the drug (referred to as Prellies) by the maid who cleaned their housing arrangements, German customers, or by Astrid Kirchherr (whose mother bought them). McCartney would usually take one, but John Lennon would often take four or five.[14] Hunter Davies asserted, in his 1968 biography of the band,[15] that their use of such stimulants then was in response to their need to stay awake and keep working, rather than a simple desire for kicks.

Jack Ruby said he was on phenmetrazine at the time he killed Lee Harvey Oswald.[16]

Preludin was also used recreationally in the US throughout the 1960s and 1970s. It could be crushed up in water, heated and injected. The street name for the drug in Washington, DC was "Bam".[17] Phenmetrazine continues to be used and abused around the world, in countries including South Korea.[18]

References

edit- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ GB 773780, Boehringer A, Boehringer E, "Improvements in or relating to the preparation of substituted morpholines"

- ^ US patent 2835669, Thomä O, "Process for the Production of Substituted Morpholines", issued 20 May 1958, assigned to C. H. Boehringer Sohn

- ^ Thomä O, Wick H (1954). "Über einige Tetrahydro-1,4-oxazine mit sympathicomimetischen Eigenschaften". Arch. Exp. Pathol. Pharmakol. 222 (6): 540. doi:10.1007/BF00246905. S2CID 25143525.

- ^ a b Martel A (January 1957). "Preludin (phenmetrazine) in the treatment of obesity". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 76 (2): 117–120. PMC 1823494. PMID 13383418.

- ^ Kalant OJ (1966). The Amphetamines: Toxicity and Addiction. ISBN 0-398-02511-8.

- ^ "Phenmetrazine hydrochloride". Journal of the American Medical Association. 163 (5): 357. February 1957. PMID 13385162.

- ^ Hampson J, Loraine JA, Strong JA (June 1960). "Phenmetrazine and dexamphetamine in the management of obesity". Lancet. 1 (7137): 1265–1267. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)92250-9. PMID 14399386.

- ^ a b Rothman RB, Baumann MH (2006). "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 6 (17): 1845–1859. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961. Archived from the original on 26 March 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Moffat AC, Osselton MD, Widdop D (2004). Clarke's Analysis of Drugs and Poisons. ISBN 0-85369-473-7.

- ^ Engelhardt A (1961). "Studies of the Mechanism of the Anti-Appetite Action of Phenmetrazine". Biochem. Pharmacol. 8 (1): 100. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(61)90520-2.

- ^ WO 2011146850, Blough BE, Rothman R, Landavazo A, Page KM, Decker AM, "Phenylmorpholines and analogues thereof", assigned to Research Triangle Institute, pages 51,54–55

- ^ Brecher EM. "The Swedish Experience". Retrieved 31 October 2009.

- ^ Miles B (1998). Paul McCartney: Many Years from Now. H. Holt. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0-8050-5248-8.

- ^ Davies H (1968). The Beatles: The Authorized Biography. New York, McGraw-Hill Book Co. p. 78. ISBN 0-07-015457-0.

- ^ Ruby J (1964). Testimony of Jack Ruby. Vol. 5. Washington: US Government Printing Office. pp. 198–99.

- ^ Dash L (1996). Rosa Lee. HarperCollins. p. 108.

- ^ Choi H, Baeck S, Jang M, Lee S, Choi H, Chung H (February 2012). "Simultaneous analysis of psychotropic phenylalkylamines in oral fluid by GC-MS with automated SPE and its application to legal cases". Forensic Science International. 215 (1–3): 81–87. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.02.011. PMID 21377815.