This article is missing information about Geography. (May 2024) |

Pripyat (/ˈpriːpjət, ˈprɪp-/ PREE-pyət, PRIP-yət; Russian: Припять, IPA: [ˈprʲipʲɪtʲ] ), also known as Prypiat (Ukrainian: Припʼять, IPA: [ˈprɪpjɐtʲ] ), is a mostly abandoned city in northern Ukraine, located near the border with Belarus. Named after the nearby river, Pripyat, it was founded on 4 February 1970 as the ninth atomgrad (a type of closed city in the Soviet Union) to serve the nearby Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, which is located in the adjacent abandoned Chernobyl.[3] Pripyat was officially proclaimed a city in 1979 and had grown to a population of 49,360[4] by the time it was evacuated on the afternoon of 27 April 1986, one day after the Chernobyl disaster.[5]

Pripyat

Прип'ять | |

|---|---|

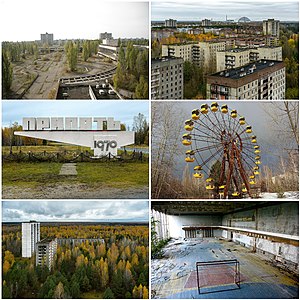

Clockwise from top-left:

| |

| Coordinates: 51°24′17″N 30°03′25″E / 51.40472°N 30.05694°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Kyiv Oblast |

| Raion |

|

| Founded | 4 February 1970 |

| City rights | 1979 |

| Government | |

| • Administration | State Agency of Ukraine on the Exclusion Zone Management |

| Area | |

• Total | 8 km2 (3 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 111 m (364 ft) |

| Population (2023) | |

• Total | 0 |

| (c. 49,000 in 1986) | |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Postal code | None (formerly 01196) |

| Area code | +380 4499[2] |

| |

Although it was located within the administrative district of Ivankiv Raion (now Vyshhorod Raion since the 2020 raion reform), the abandoned municipality now has the status of city of regional significance within the larger Kyiv Oblast, and is administered directly from the capital of Kyiv. Pripyat is supervised by the State Emergency Service of Ukraine which manages activities for the entire Chernobyl exclusion zone. Following the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the entire population of Pripyat was moved to the purpose-built city of Slavutych.

History

editEarly years

editAccess to Pripyat, unlike cities of military importance, was not restricted before the disaster as the Soviet Union deemed nuclear power stations safer than other types of power plants. Nuclear power stations were presented as achievements of Soviet engineering, harnessing nuclear power for peaceful projects. The slogan "peaceful atom" (Russian: мирный атом, romanized: mirnyy atom) was popular during those times. The original plan had been to build the plant only 25 km (16 mi) from Kyiv, but the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, among other bodies, expressed concern that would be too close to the city. As a result, the power station and Pripyat[6] were built at their current locations, about 100 km (62 mi) from Kyiv.[7]

Post-Chernobyl disaster

editIn 1986, the city of Slavutych was constructed to replace Pripyat. After Chernobyl, this was the second-largest city for accommodating power plant workers and scientists in the Commonwealth of Independent States.

One notable landmark often featured in photographs in the city and visible from aerial-imaging websites is the long-abandoned Ferris wheel located in the Pripyat amusement park, which had been scheduled to have its official opening five days after the disaster, in time for May Day celebrations.[8][9] The Azure Swimming Pool and Avanhard Stadium are two other popular tourist sites.

On 4 February 2020, former residents of Pripyat gathered in the abandoned city to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Pripyat's establishment. This was the first time former residents returned to the city since its abandonment in 1986.[10] The 2020 Chernobyl Exclusion Zone wildfires reached the outskirts of the town, but they did not reach the plant.[11]

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the city was occupied by Russian forces during the Battle of Chernobyl after several hours of heavy fighting.[12] On 31 March Russian troops withdrew from the plant and other parts of Kyiv Oblast.[13][14] On 3 April Ukrainian troops took control of Pripyat again.[15][16]

Infrastructure and statistics

editThe following statistics are from 1 January 1986.[17]

- The population was 49,400. The average age was about 26 years old. Total living space was 658,700 m2 (7,090,000 sq ft): 13,414 apartments in 160 apartment blocks, 18 halls of residence accommodating up to 7,621 single males or females, and eight halls of residence for married or de facto couples.

- Education: 15 kindergartens and elementary schools for 4,980 children, and five secondary schools for 6,786 students.

- Healthcare: one hospital could accommodate up to 410 patients, and three clinics.

- Trade: 25 stores and malls; 27 cafes, cafeterias, and restaurants collectively could serve up to 5,535 customers simultaneously. 10 warehouses could hold 4,430 tons of goods.

- Culture: the Palace of Culture Energetik; a cinema; and a school of arts, with eight different societies.

- Sports: 10 gyms, 10 shooting galleries, three indoor swimming-pools, two stadiums.

- Recreation: one park, 35 playgrounds, 18,136 trees, 33,000 rose plants, 249,247 shrubs.

- Industry: four factories with annual turnover of 477,000,000 rubles. One nuclear power plant with four reactors (plus two more planned).

- Transportation: Yanov railway station, 167 urban buses, plus the nuclear power plant car park with 400 spaces.

- Telecommunication: 2,926 local phones managed by the Pripyat Phone Company, plus 1,950 phones owned by Chernobyl power station's administration, Jupiter plant, and Department of Architecture and Urban Development.

Safety

editA concern is whether it is safe to visit Pripyat and its surroundings. The Zone of Alienation is considered relatively safe to visit, and several Ukrainian companies offer guided tours around the area. In most places within the city, the level of radiation does not exceed an equivalent dose of 1 μSv (one microsievert) per hour.[18]

Climate

editThe climate of Pripyat is designated as Dfb (Warm-summer humid continental climate) on the Köppen Climate Classification System.[19]

| Climate data for Pripyat | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −3 (27) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

13.2 (55.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.5 (74.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.9 (75.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

11.6 (53.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −6.1 (21.0) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

0.1 (32.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −9.1 (15.6) |

−9 (16) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

3.7 (38.7) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

13.7 (56.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

8.6 (47.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

| Source: [20] | |||||||||||||

In popular culture

editFilms

edit(Alphabetical by title)

- The horror film Chernobyl Diaries (2012) was inspired by the Chernobyl disaster in 1986 and takes place in Pripyat.[21]

- The majority of the film Land of Oblivion (2011) was shot on location in Pripyat.

- Pripyat is featured in the History Channel documentary Life After People.

- The drone manufacturer DJI produced Lost City of Chernobyl (May 2015), a documentary film about the work of photographer and cinematographer Philip Grossman and his five-year project in Pripyat and the Zone of Exclusion.[22]

- Filmmaker Danny Cooke used a drone to capture shots of the abandoned amusement park, some residential shots of decaying walls, children's toys, and gas masks, and collected them in a 3-minute short film Postcards From Chernobyl (released in November 2014), while making footage for the CBS News 60 Minutes episode "Chernobyl: The Catastrophe That Never Ended" (early 2014).[23][24]

- With the help of drones, aerial views of Pripyat were shot and later edited to appear as a deserted London in the film The Girl with All the Gifts (2016).[25]

- The documentary White Horse (2008) was filmed in Pripyat.[26]

Literature

edit(Alphabetical by artist)

- Markiyan Kamysh's novel, Stalking the Atomic City: Life Among the Decadent and the Depraved of Chornobyl, is about illegal trips to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.[27]

- The Chernobyl Poems of Lyubov Sirota by the professor of Washington University Paul Brians

- Lyubov Sirota’s novel "The Pripyat Syndrome"; Language: English, Publisher: Independently published (February 18, 2021), Paperback: 202 pages, ISBN 979-8710522875 – Lyubov Sirota (Author), Birgitta Ingemanson (Editor), Paul Brians (Editor), A. Yukhimenko (Illustrator), Natalia Ryumina (Translator)

- Much of the James Rollins' novel The Last Oracle takes place in Pripyat and around Chernobyl. The story revolves around a team of American "Killer Scientist" special agents who must stop a terrorist plot to unleash on the world the radiation of Lake Karachay, during the installation of the new sarcophagus over the Chernobyl nuclear power plant.

- The exclusion zone is the setting for Karl Schroeder's science fiction short story "The Dragon of Pripyat".

Music

edit(Alphabetical by artist)

- The Ukrainian singer Alyosha recorded most of the video for her Eurovision 2010 entry, "Sweet People", in Pripyat.

- Ash, the rock band from Northern Ireland, has a song titled "Pripyat" included in their album A–Z Vol.1.

- The song "Dead City" (Ukrainian: Мертве Місто) by the Ukrainian symphonic metal band DELIA is about Pripyat, and scenes from the music video were shot in the city. DELIA's vocalist, Anastasia Sverkunova, was born in Pripyat just before the Chernobyl disaster.[28]

- In 2006, musician Example featured Pripyat in his 18-minute documentary of the ghost town and in his promotional video for his track, "What We Made".

- The Scottish post-rock band Mogwai included a song titled "Pripyat" on their album Atomic (2016), which is a soundtrack to Mark Cousins' documentary Atomic, Living in Dread and Promise.

- The Irish folk-rock singer Christy Moore included a song called "Farewell to Pripyat" on his album Voyage (1989), the song credited to Tim Dennehy.

- Marillion guitarist Steve Rothery's first solo album is titled The Ghosts of Pripyat (2014).

- The Australian rapper Seth Sentry included the two-part song "Pripyat" in his album Strange New Past (2015).

- The English rock band Suede used the city to shoot their music video clip Life Is Golden, including takes of the Azure Swimming Pool, Pripyat amusement park, and Polissya hotel.

- The Italian Rapper Caparezza has a song titled "Come Pripyat" on his album Exuvia, released in 2021.[29]

- The Belarusian post-punk band Molchat Doma released a music video for their song titled, "Waves" (Russian: Волны) as part of their album Etazhi. The music video was filmed in Pripyat through a series of varying drone shots; displaying famous landmarks of the abandoned city.[30]

Television

edit(Alphabetical by series)

- The 60 Minutes episode "Chernobyl: The Catastrophe That Never Ended" (early 2014) aired on CBS.[23][31]

- HBO's drama miniseries Chernobyl (2019) is based on the Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster. The scenes set in 1986 Pripyat were filmed in Vilnius, Lithuania.

- in the Chris Tarrant: Extreme Railways Season 5 episode "Extreme Nuclear Railway: A Journey Too Far?" (episode 22), Chris Tarrant visits Chernobyl on his journey through Ukraine.

- Discovery Science Channel's Mysteries of the Abandoned episode "Chernobyl's Deadly Secrets",[32] produced and hosted by Philip Grossman,[33] was filmed over a four-day period in Pripyat and the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, in 2017.

- The Animal Planet nature investigation series River Monsters conducted an extensive 2013 investigation within Pripyat, the exclusion zone, and the Chernobyl Power Plant in search of a radioactive mutated wels catfish.[34]

- A David Attenborough documentary depicts natural life in Pripyat.[vague]

Video games

editCall of Duty 4: Modern Warfare's (and its remaster's) single-player campaign includes levels "All Ghillied Up" and "One Shot, One Kill", which are set in Pripyat. The former is considered to be one of the greatest video game levels of all time.[35]

The S.T.A.L.K.E.R franchise is set around the Chornobyl exclusion zone, and prominently features Pripyat in the series, namely in S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Call of Pripyat.

Transport

editThe city was served by Yaniv station on the Chernihiv–Ovruch railway. It was an important passenger hub of the line and was located between the southern suburb of Pripyat and Yaniv. An electric train terminus of Semikhody, built in 1988 and located in front of the nuclear plant, is currently the only operating station near Pripyat connecting it to Slavutych.[36]

Notable people

edit- Markiyan Kamysh (born 1988) writer, illegal Chernobyl explorer ("stalker")

- Vitali Klitschko (born 1971) politician, mayor of Kyiv and former professional boxer

- Wladimir Klitschko (born 1976) former professional boxer

- Alexander Sirota (born 1976) photographer, journalist and filmmaker

- Lyubov Sirota (born 1956) poet, writer, playwright, journalist and translator

Gallery

edit-

Pripyat in winter

-

Pripyat in winter

-

A gate in Pripyat city, 2000

-

Ferris wheel of the Pripyat amusement park

-

Pripyat city limit sign with a radiation dosimeter

-

Palace of Culture Energetik — artistic, cultural, entertainment and recreational activities center

-

The former football stadium of Pripyat

-

Abandoned football ground

-

Forest area near the city

-

Pripyat pier

-

Abandoned school

-

Pripyat after the disaster

-

Pripyat skyline

-

Pripyat bumper car floor

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Elevation of Pripyat, Scotland Elevation Map, Topography, Contour". Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ "City Phone Codes". Archived from the original on 15 August 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Pripyat: Short Introduction Archived 11 July 2012 at archive.today

- ^ "Chernobyl and Eastern Europe: My Journey to Chernobyl 6". Chernobylee.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ "Pripyat – City of Ghosts". chernobylwel.com. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 13 February 2016.

- ^ "History of the Pripyat city creation". chornobyl.in.ua. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Anastasia. "dirjournal.com". Info Blog. Archived from the original on 17 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Hjelmgaard, Kim (17 April 2016). "Pillaged and peeling, radiation-ravaged Pripyat welcomes 'extreme' tourists". USA Today. Archived from the original on 29 April 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Gais, Hannah; Steinberg, Eugene (26 April 2016). "Chernobyl in Spring". Pacific Standard. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ LEE, PHOTOS BY ASSOCIATED PRESS, EDITED BY AMANDA (4 February 2020). "AP Gallery: Chernobyl town Pripyat celebrates 50th anniversary". Columbia Missourian. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Roth, Andrew (13 April 2020). "Ukraine: wildfires draw dangerously close to Chernobyl site". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ "Fighting breaks out near Chernobyl, says Ukrainian president". The Independent. 24 February 2022. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Russia Hands Control of Chernobyl Back to Ukraine, Officials Say". Wall Street Journal. 31 March 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Ukrainian flag was raised at the Chornobyl nuclear power plant Archived 2 April 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (2 April 2022)

- ^ Kyiv region: Ukrainian military take control of Pripyat and section of border Archived 25 June 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Ukrainska Pravda (3 April 2022)

- ^ "Ukrainian forces regain control of Pripyat, the ghost town near the Chernobyl nuclear plant". 3 April 2022. Archived from the original on 3 April 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Припять в цифрах Archived 13 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine ("Pripyat in Numbers"), a page from Pripyat website

- ^ "Radiation levels". The Chernobyl Gallery. 24 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Mindat.org https://www.mindat.org/loc-271143.html Archived 6 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Prypiat climate". Archived from the original on 14 February 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Chernobyl Diaries at IMDb

- ^ DJI (14 August 2015), DJI Stories – The Lost City of Chernobyl, archived from the original on 25 August 2015, retrieved 24 March 2016

- ^ a b "Witness a Drone's Eye View of Chernobyl's Urban Decay". The Creators Project. 24 November 2014. Archived from the original on 26 November 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "من فوق.. كيف يبدو ما بقي من تشيرنوبل بعد 30 عاما من الكارثة النووية؟". CNN Arabic. December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (4 August 2016). "The story behind 'The Girl With All The Gifts'". Screen International. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ^ White Horse at IMDb

- ^ "Stalking the Atomic City by Markiyan Kamysh". Penguin Random House Canada. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 19 August 2021.

- ^ "DELIA". Archived from the original on 11 December 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Exuvia". Record Store Day. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ "Molchat Doma - Volny (Official Lyrics Video) молчат дома - волны". YouTube. 5 September 2020. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ^ "من فوق.. كيف يبدو ما بقي من تشيرنوبل بعد 30 عاما من الكارثة النووية؟". CNN Arabic. December 2014. Archived from the original on 24 July 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- ^ "Philip Grossman - Mysteries of the Abandoned Cast". Science. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ "Philip Ethan Grossman". IMDb. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Atomic Assassin". Animal Planet. Archived from the original on 4 May 2021. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

- ^ Burford, GB (23 October 2014). "Why Modern Warfare's 'All Ghillied Up' Is One Of Gaming's Best Levels". Kotaku. Univision Communications. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2024.

- ^ "Radioactive Railroad". Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

External links

edit- Pripyat-Info – Informational Portal: «PRIPYAT :: EXCLUSION ZONE»

- Pripyat.com – Site created by former residents

- 25 years of satellite imagery over Chernobyl Pripyat map

- pripyatpanorama.com Archived 14 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine – Pripyat in Panoramas Project

- exploringthezone.com Archived 12 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine – 5-year project documenting the Pripyat and Chernobyl Zone

- Pripyat-city.ru Archived 17 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine – Blog related to Pripyat

- ChernobylGallery.com – Photographs of Pripyat and Chernobyl

- Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, Pripyat 2018 on YouTube – 2018 Footage of Pripyat and Chernobyl