The Pygmies (‹See Tfd›Greek: Πυγμαῖοι Pygmaioi, from the adjective πυγμαῖος, from the noun πυγμή pygmē "fist, boxing, distance from elbow to knuckles," from the adverb πύξ pyx "with the fist") were a tribe of diminutive humans in Greek mythology.

Attestations

editAccording to the Iliad,[1] they were involved in a constant war with the cranes, which migrated in winter to their homeland on the southern shores of the earth-encircling river Oceanus:

Now when the men of both sides were set in order by their leaders,

the Trojans came on with clamour and shouting, like wildfowl,

as when the clamour of cranes goes high to the heavens,

when the cranes escape the winter time and the rains unceasing

and clamorously wing their way to the streaming Ocean,

bringing to the Pygmaian men bloodshed and destruction:

at daybreak they bring on the baleful battle against them.

According to Aristotle in History of Animals,[2] the story is true:

these birds [the cranes] migrate from the steppes of Scythia to the marshlands south of Egypt where the Nile has its source. And it is here, by the way, that they are said to fight with the pygmies; and the story is not fabulous, but there is in reality a race of dwarfish men, and the horses are little in proportion, and the men live in caves underground.

Hesiod wrote that Epaphus, son of Zeus, through his daughters was the ancestor of the "dark Libyans, and high-souled Aethiopians, and the Underground-folk and feeble Pygmies".[3]

According to Stephanus of Byzantium, the tribe of Pygmies was descended from Pygmaios, son of Doros, son of Epaphus.[4]

One story in Ovid describes the origin of the age-old battle, speaking of a Pygmy Queen named Gerana who offended the goddess Hera with her boasts of superior beauty, and was transformed into a crane.

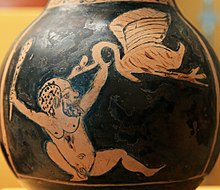

In art the scene was popular with little Pygmies armed with spears and slings, riding on the backs of goats, battling the flying cranes. The 2nd-century BC tomb near Panticapaeum, Crimea "shows the battle of human pygmies with a flock of herons".[5]

The Pygmies were often portrayed as pudgy, comical dwarves.

In another legend, the Pygmies once encountered Heracles, and climbing all over the sleeping hero attempted to bind him down, but when he stood up they fell off. The story was adapted by Jonathan Swift as a template for Lilliputians. [citation needed]

St. Augustine (354–430) mentions the Pygmies in The City of God, Book 16, chapter 8 entitled, "Whether Certain Monstrous Races of Men Are Derived From the Stock of Adam or Noah's Sons".[6]

Later Greek geographers and writers attempted to place the Pygmies in a geographical context. Sometimes they were located in far India, at other times near the Ethiopians of Africa. The Pygmy bush tribes of central Africa were so named after the Greek mythological creatures by European explorers in the 19th century.

Greeks used the proverbial phrase "fitting Pygmies' spoils onto a colossus", in reference "to those toiling in vain" and also in reference "to those bringing together incompatible things, and especially when we compare tiny things to huge ones".[7][8][9]

Descriptions in literature

editAncient

editFrom Pliny's Natural History:

Beyond these in the most outlying mountain region we are told of the Three-Span (Trispithami) Pygmae who do not exceed three spans, that is, twenty-seven inches, in height; the climate is healthy and always spring-like, as it is protected on the north by a range of mountains; this tribe Homer has also recorded as being beset by cranes. It is reported that in springtime their entire band, mounted on the backs of rams and she-goats and armed with arrows, goes in a body down to the sea and eats the cranes' eggs and chicks, and that this outing occupies three months; and that otherwise they could not protect themselves against the flocks of cranes would grow up; and that their houses are made of mud and feathers and egg-shells. Aristotle says that the Pygmies live in caves, but in the rest of this statement about them he agrees with the other authorities.[10]

From The Life of Apollonius of Tyana by Flavius Philostratus:

And as to the pigmies, he said that they lived underground, and that they lay on the other side of the Ganges and lived in the manner which is related by all. As to men that are shadow-footed or have long heads, and as to the other poetical fancies which the reatise of Scylax recounts about them, he said that they didn't live anywhere on the earth, and least of all in India.[11]

From Imagines by Philostratus:

HERACLES AMONG THE PYGMIES.

While Herakles is asleep in Libya after conquering Antaeus, the Pygmies set upon him with the avowed intention of avenging Antaeus; for they claim to be brothers of Antaeus, high-spirited fellows, not athletes, indeed, nor his equals at wrestling, but earth-born and quite strong besides, and when they come up out of the earth the sand billows in waves. For the Pygmies dwell in the earth just like ants and store their provisions underground, and the food they eat is not the property of others but their own and raised by themselves. For they sow and reap and ride on a cart drawn by pigmy horses, and it said that they use an axe on stalks of grain, believing that these are trees. But ah, their boldness! Here they are advancing against Heracles and undertaking to kill him in his sleep; though they would not fear him even if he were awake. Meanwhile he sleeps on the soft sand, since weariness has crept over him in wrestling; and, filled with sleep, his mouth open, he draws full breaths deep in his chest, and Sleep himself stands over him in visible form, making much, I think, of his own part in the fall of Heracles. Antaeus also lies there, but whereas art paints Heracles as alive and warm, it represents Antaeus as dead and withered and abandons him to Earth. The army of the Pygmies envelops Heracles; while this one phalanx attacks his left hand, these other two companies march against his right hand as being stronger; bowmen and a host of slingers lay siege to his feet, amazed at the size of his shin; as for those who advance against his head, the Pygmy King has assumed the command at this point, which they think will offer the stoutest resistance, and they bring engines of war to bear against it as if it were a citadel – fire for his hair, mattocks for his eyes, doors of a sort for his mouth, and these, I fancy, are gates to fasten on his nose, so that Heracles may not breathe when his head has been captured. All these things are being done, to be sure, around the sleeping Heracles; but lo! he stands erect and laughs at the danger, and sweeping together the hostile forces he puts them in his lion' skin, and I suppose he is carrying them to Eurystheus.[12][13]

From Deipnosophistae by Athenaeus:

Boeus says also, of the crane, that she had been a woman eminent among the Pygmies, named Gerana. She, honoured as a god by her citizens, held the true gods in low esteem herself, especially Hera and Artemis. Hera, therefore, became angry, metamorphosed her into a bird of ugly shape, and made her an enemy and hateful to the Pygmies who had honored her; Boeus also says that from her and Nicodanas was born the land tortoise.[14]

Medieval

editFrom The Travels of Sir John Mandeville:

That river goeth through the land of Pigmies, where that the folk be of little stature, that be but three span long, and they be right fair and gentle, after their quantities, both the men and the women. And they marry them when they be half year of age and get children. And they live not but six year or seven at the most; and he that liveth eight year, men hold him there right passing old. These men be the best workers of gold, silver, cotton, silk and of all such things, of any other that be in the world. And they have oftentimes war with the birds of the country that they take and eat. This little folk neither labour in lands ne in vines; but they have great men amongst them of our stature that till the land and labour amongst the vines for them. And of those men of our stature have they as great scorn and wonder as we would have among us of giants, if they were amongst us. There is a good city, amongst others, where there is dwelling great plenty of those little folk, and it is a great city and a fair. And the men be great that dwell amongst them, but when they get any children they be as little as the pigmies. And therefore they be, all for the most part, all pigmies; for the nature of the land is such. The great Chan let keep this city full well, for it is his. And albeit, that the pigmies be little, yet they be full reasonable after their age, and can both wit and good and malice enough.[15]

Modern

editFrom Tanglewood Tales: The Pygmies by Nathaniel Hawthorne:

Among the Pygmies, I suppose, if one of them grew to the height of six or eight inches, he was reckoned a prodigiously tall man. It must have been very pretty to behold their little cities, with streets two or three feet wide, paved with the smallest pebbles, and bordered by habitations about as big as a squirrel's cage. The king's palace attained to the stupendous magnitude of Periwinkle's baby house, and stood in the center of a spacious square, which could hardly have been covered by our hearth- rug. Their principal temple, or cathedral, was as lofty as yonder bureau, and was looked upon as a wonderfully sublime and magnificent edifice. All these structures were built neither of stone nor wood. They were neatly plastered together by the Pygmy workmen, pretty much like birds' nests, out of straw, feathers, egg shells, and other small bits of stuff, with stiff clay instead of mortar; and when the hot sun had dried them, they were just as snug and comfortable as a Pygmy could desire.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Homer 3.1-7

- ^ Aristotle, 8.12, 892a12

- ^ Hesiod, Fragments, CW.F40

- ^ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Pygmaioi (Πυγμαῖοι)

- ^ Kubiĭovych and Shevchenka, p. 558.

- ^ Augustine, Chapter 8. – Whether Certain Monstrous Races of Men Are Derived From the Stock of Adam or Noah's Sons

- ^ Suda, nu,387

- ^ Suda, eta,462

- ^ Suda, alpha,1002

- ^ Pliny. Natural History, 7.23–7.30.

- ^ Flavius Philostratus, The Life of Apollonius of Tyana, translated by F. C. Conybeare, volume II, book III.XLVIII., 1921, p. 331.

- ^ Philostratus, Imagines, translated by Arthur Fairbanks (1864–1944) edition of 1931

- ^ Philostratus, Imagines, Greek

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 9.393, translated by Charles Burton Gulick (1868–1962), from the Loeb Classical Library edition of 1927–41, books 10–end by Charles Duke Yonge (1812–1891)

- ^ The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, Chapter XXII, Macmillan and Co. edition, 1900.

Sources

edit- Aristotle, History of Animals. Translated by D'Arcy Wentworth Thompson. Internet Classics Archive.

- Homer, The Iliad of Homer. Translated and with an Introduction by Richmond Lattimore. The University of Chicago Press, 1961. ISBN 0-226-46940-9

- Kubiĭovych, Volodymyr and Shevchenka, Naukove tovarystvo im. Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopaedia. University of Toronto, 1963. ISBN 0-8020-3261-3

- Mandeville, John, The Travels of Sir John Mandeville: The Fantastic 14th-Century Account of a Journey to the East, ISBN 0-486-44378-7

- Ritson, Joseph, Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To which are prefixed two dissertations: 1. On Pygmies. 2. On Fairies, London, 1831, (Adamant Media Corporation, 2004) ISBN 1-4021-4753-8