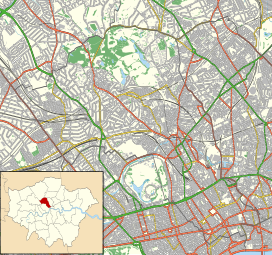

Regent's Park (officially The Regent's Park) is one of the Royal Parks of London. It occupies 410 acres (170 ha) in north-west Inner London, administratively split between the City of Westminster and the Borough of Camden (and historically between Marylebone and Saint Pancras parishes).[1] In addition to its large central parkland and ornamental lake, it contains various structures and organizations both public and private, generally on its periphery, including Regent's University and London Zoo.

| Regent's Park | |

|---|---|

| Type | Public park |

| Location | London |

| Coordinates | 51°31′56″N 00°09′24″W / 51.53222°N 0.15667°W |

| Area | 410 acres (170 ha) (1.6 km²) |

| Operated by | The Royal Parks |

| Open | Open, year-round |

| Status | Existing |

| Website | www |

What is now Regent's Park came into possession of the Crown upon the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1500s, and was used for hunting and tenant farming. In the 1810s, the Prince Regent proposed turning it into a pleasure garden. The park was designed by John Nash and James and Decimus Burton. Its construction was financed privately by James Burton after the Crown Estate rescinded its pledge to do so, and included development on the periphery of townhouses and expensive terrace dwellings. The park is Grade I listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[2]

Description

editThe park has an outer ring road called the Outer Circle (4.45 km) and an inner ring road called the Inner Circle (1 km), which surrounds the most carefully tended section of the park, Queen Mary's Gardens. Apart from two link roads between these two, the park is reserved for pedestrians (with the exception of The Broad Walk between Chester Road and the Outer Circle, which is a shared use path). The south, east and most of the west side of the park are lined with elegant white stucco terraces of houses designed by John Nash and Decimus Burton. Running through the northern end of the park is Regent's Canal, which connects the Grand Union Canal to London's historic docks. The 166 ha (410-acre) park[3] is mainly open parkland with a wide range of facilities and amenities, including gardens; a lake with a heronry, waterfowl and a boating area; sports pitches; and children's playgrounds. The northern side of the park is the home of London Zoo and the headquarters of the Zoological Society of London. There are several public gardens with flowers and specimen plants, including Queen Mary's Gardens in the Inner Circle, in which the Open Air Theatre stands; the formal Italian Gardens and adjacent informal English Gardens in the south-east corner of the park; and the gardens of St John's Lodge. Winfield House, the official residence of the U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom, stands in private grounds in the western section of the park, near the capital's first large mosque.

South of the Inner Circle is dominated by Regent's University London, home of the European Business School London, Regent's American College London (RACL) and Webster Graduate School among others.

Abutting the northern side of Regent's Park is Primrose Hill, another park which, with a height of 64 m (210 ft),[4] has a clear view of central London to the south-east, as well as Belsize Park and Hampstead to the north. Primrose Hill is also the name given to the immediately surrounding district.

Management

editThe public areas of Regent's Park are managed by The Royal Parks, a charity. The Crown Estate Paving Commission is responsible for managing certain aspects of the built environment of Regent's Park. The park lies within the boundaries of the City of Westminster and the London Borough of Camden, but those authorities have only peripheral input to the management of the park. The Crown Estate owns the freehold of Regent's Park.

History

editIn the Middle Ages the land was part of the manor of Tyburn, acquired by Barking Abbey. The 1530s Dissolution of the Monasteries meant Henry VIII appropriated it, under that statutory forfeiture with minor compensation scheme. It has been state property since. It was set aside as a hunting and forestry park, Marylebone Park, from that Dissolution until 1649 after which it was let as small-holdings for hay and dairy produce.[5]

Development by John Nash, James Burton, and Decimus Burton

editAlthough the park was initially the idea of the Prince Regent, and was named for him,[6] James Burton, the pre-eminent London property developer, was responsible for the social and financial patronage of the majority of John Nash's London designs,[7] and for their construction.[8] Architectural scholar Guy Williams has written, "John Nash relied on James Burton for moral and financial support in his great enterprises. Decimus had showed precocious talent as a draughtsman and as an exponent of the classical style... John Nash needed the son's aid, as well as the father's".[7] Subsequent to the Crown Estate's refusal to finance them, James Burton agreed to personally finance the construction projects of John Nash at Regent's Park, which he had already been commissioned to construct:[9][8] consequently, in 1816, Burton purchased many of the leases of the proposed terraces around, and proposed villas within Regent's Park,[9] and, in 1817, Burton purchased the leases of five of the largest blocks on Regent Street.[9] The first property to be constructed in or around Regent's Park by Burton was his own mansion: The Holme, which was designed by his son, Decimus Burton, and completed in 1818.[9] Burton's extensive financial involvement "effectively guaranteed the success of the project".[9] In return, Nash agreed to promote the career of Decimus Burton.[9] Such were James Burton's contributions to the project that the Commissioners of Woods described James, not Nash, as "the architect of Regent's Park".[10]

Contrary to popular belief, the dominant architectural influence in many of the Regent's Park projects – including Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Chester Terrace, Clarence Terrace, and the villas of the Inner Circle, all of which were constructed by James Burton's company[9] – was Decimus Burton, not John Nash, who was appointed architectural "overseer" for Decimus's projects.[10] To the chagrin of Nash, Decimus largely disregarded his advice and developed the Terraces according to his own style, to the extent that Nash sought the demolition and complete rebuilding of Chester Terrace, but in vain.[11] Decimus's terraces were built by his father James.[12][9]

The Regent's Park scheme was integrated with other schemes built for the Prince Regent by the triplet of Nash, James Burton, and Decimus Burton: these included Regent Street and Carlton House Terrace in a grand sweep of town planning stretching from St. James's Park to Primrose Hill. The scheme is considered one of the first examples of a garden suburb and continues to influence the design of suburbs.[13] The park was first opened to the general public in 1835, initially two days a week. The 1831 diary of William Copeland Astbury describes in detail his daily walks in and around the park, with references to the Zoo, the canal, and surrounding streets, as well as features of daily life in the area.[14]

Subsequent history

editOn 15 January 1867, forty people died when the ice cover on the boating lake collapsed and over 200 people plunged into the lake.[15] The lake was subsequently drained and its depth reduced to four feet before being reopened to the public.[16]

Late in 1916, the Home Postal Depot, Royal Engineers moved to a purpose-built wooden building (200,000 sq ft) on Chester Road, Regent's Park. This new facility contained the depot's administration offices, a large parcel office and a letter office, these last two previously being at the Mount Pleasant Mail Centre. HM King George V and HM Queen Mary visited the depot on 11 December 1916. The depot vacated the premises in early 1920.[17]

Queen Mary's Gardens, in the Inner Circle, were created in the 1930s, bringing that part of the park into use by the general public for the first time. The site had originally been used as a plant nursery and had later been leased to the Royal Botanic Society.

In July 1982, an IRA bomb was detonated at the bandstand, killing seven soldiers.

The sports pitches, which had been relaid with inadequate drainage after the Second World War, were relaid between 2002 and 2004, and in 2005 a new sports pavilion was constructed.

On 7 July 2006 the park held an event for people to remember the events of the 7 July 2005 London bombings. Members of the public placed mosaic tiles on to seven purple petals. Later bereaved family members laid yellow tiles in the centre to finish the mosaic.

Sport

editSports are played in the park including cycling, tennis, netball, athletics, cricket, softball, rounders, football, hockey, Australian rules football, rugby, ultimate Frisbee, and running. Belsize Park Rugby Football Club play their home games in the park.

There are three playgrounds and there is boating on the lake.

Sports take place in an area called the Northern Parkland, and are centred on the Hub. This pavilion and underground changing rooms was designed by David Morley Architects and Price & Myers engineers, and opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 2005.[citation needed] It won the IStructE Award for Community or Residential Structures in 2006.

The Outer Circle is used by road cyclists. One circuit is 4.45 km. A number of amateur cycling clubs that meet regularly to complete laps of the Outer Circle for exercise and leisure. Prominent clubs include: Regent's Park Rouleurs (RPR), London Baroudeurs (LBCC), Islington Cycling Club (ICC), Cycle Club London (CCL), Rapha Cycle Club (RCC). Many cyclists track & log their rides using the online social network site Strava. As at January, 2018 – some 22,000 cyclists had completed & logged 1.6mn laps of the park using the Strava app.[18] In 2015, Regent's Park Cyclists was formed to represent the interest of cyclists and cycling clubs that use the Inner & Outer Circle.[19]

The park was scheduled to play a role in the 2012 Summer Olympics, hosting the baseball and softball events, but these sports were dropped from the Olympic programme with effect from 2012. The Olympic cycling road race was supposed to go through Regent's Park, as was the cycling road race in the 2012 Summer Paralympics, but the routes were changed.[20][21]

Terraces

editThe neoclassical terraces are grand examples of the English townhouse. Sometimes they are collectively called the "Nash terraces", but other architects contributed. Clockwise from the north, they are:

- Gloucester Gate: A terrace of 11 houses designed by Nash and built by Richard Mott in 1827.[22]

- Cumberland Terrace: Designed by Nash and built by William Mountford Nurse in 1826.[23]

- Chester Terrace: The longest façade in the park designed by Nash and Decimus Burton. Was built by James Burton in 1825.[24]

- Cambridge Terrace: Designed by Nash and built by Richard Mott in 1825. Cambridge Gate was added in 1876–80.[25]

- York Terrace: Designed by Nash and Decimus Burton the eastern half built by James Burton and the western half built by William Mountford Nurse.[26]

- Cornwall Terrace: Consists of 19 houses designed by Decimus Burton and built by James Burton.[27]

- Clarence Terrace: The smallest terrace, designed by Decimus Burton.[28]

- Sussex Place: Originally 26 houses designed by Nash and built by William Smith in 1822–23, rebuilt in the 1960s behind the original façade to house the London Business School.[29]

- Hanover Terrace: Designed by Nash in 1822 and built by John Mckell Aitkens.[30]

- Kent Terrace: Designed by Nash and built by William Smith in 1827.[31]

Immediately south of the park are Park Square and Park Crescent, also designed by Nash.

Villas

editNine villas were initially built in the park. There follows a list of their names as shown on Christopher and John Greenwood's map of London (second edition, 1830),[32] with details of their subsequent fates:

Close to the western and northern edges of the park

edit- Hertford Villa (later known as St Dunstan's): Damaged by fire. Rebuilt as Winfield House in the 1930s and now the American Ambassador's residence, with the second-largest private garden in London after the King's garden at Buckingham Palace.

- Nuffield Lodge: A private residence currently owned by the Oman royal family), and previously owned by Robert Holmes à Court. Nuffield Lodge is said to have one of the largest gardens in central London after Buckingham Palace and Winfield House. The garden runs along the edge of Regent's Canal.

- Hanover Lodge: A private residence was the subject of a Court Case in the early 21st century (won by Westminster City Council against the architect, Quinlan Terry, and contractor, Walter Lilly & Co) that ruled that two Grade II listed buildings on the property had been illegally demolished while the property was leased to Conservative peer Lord Bagri.

- Albany Cottage: Demolished. Site now occupied by London Central Mosque.

- Holford House (Stanford's map of 1862): Built in 1832 north of Hertford House, it was the largest of the villas at that time. From 1856 it was occupied by Regent's Park College (which subsequently moved to Oxford in 1927). In 1944 Holford House was destroyed by a bomb during World War II. Demolished in 1948.

- Between 1988 and 2004, six new villas were built by the Crown Estate and property developers at the north western edge of the park, between the Outer Circle and the Regent's Canal. They were designed by the English Neo-Classical architect Quinlan Terry, who designed each house in a different classical style, intended to be representative of the variety of classical architecture, naming them the Veneto Villa, Doric Villa, Corinthian Villa, Ionic Villa, Gothick Villa and the Regency Villa respectively.[33]

Around the Inner Circle

edit- St John's Lodge: A private residence (Brunei royal family) but part of its garden, designed by Colvin and Moggridge Landscape Architects in 1994, is open to the public. St John's Lodge was the first villa to be constructed in the park by John Raffield.[34]

- The Holme: A private residence (Saudi royal family) but its garden is open several days a year via the National Gardens Scheme.[35] It has been described as 'one of the most desirable private homes in London' by architectural scholar Guy Williams,[36] and as 'a definition of Western civilization in a single view' by architectural critic Ian Nairn.[37] The Holme was the second villa to be built in Regent's Park.

- South Villa: Site of George Bishop's Observatory, which closed when its owner died in 1861 (instruments and dome moved to Meadowbank, Twickenham in 1863). Regent's University London now stands on the site, one of the two largest groups of buildings in the park, alongside London Zoo.

- Regent's University London has its campus just southwest of the Inner Circle. Previously was home to Bedford College.

Close to the eastern edge of the park

edit- Sir Herbert Taylor's Villa: Demolished. Site now part of open parkland. He was Master of St Katherine's Hospital when it was based at Regent's Park.

- International Students House, London

- The Diorama, 18 Park Square East, opened in 1823, closed 1852. A forerunner of the cinema.

More attractions

edit- Park Crescent's breathtaking façades by John Nash have been preserved, although the interiors were rebuilt as offices in the 1960s.

- The Camden Green Fair is held in Regent's Park as part of an ongoing effort to encourage citizens of London to go Green.

- The fountain erected through the gift of Cowasji Jehangir Readymoney is on The Broadwalk, between Chester Road and the Outer Circle.

Transport

editNearest Tube stations

editThere are five London Underground stations located on or near the edges of Regent's Park:[38]

Nearest railway stations

editCultural references

editIn film and television

edit- In 28 Weeks Later (2007), the surviving members of the American military escort Tammy and Andy to Regent's Park to get evacuated out of London.

- Regent's Park is the setting and closing scene for the black comedy film Withnail and I (1987).

- The Regent's Park is also the primary setting of the season three episode "Three Legs Good" of the cozy mystery television series Rosemary & Thyme.

- Regent's Park is the setting of Cruella de Vil's fashion show in Disney's live-action prequel film Cruella (2021).

- Regent's Park is the setting of the modern headquarters of MI5 for the spy thriller television series Slow Horses (2022).

- In Disney's One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961), Pongo is barking the alert from Regent's Park. As stated by the great dane.

In gaming

edit- Much like the example above, the video game tie-in for Disney's live-action film 102 Dalmatians (2000) features Regent's Park as the game's first level.

In literature

edit- In Elizabeth Bowen's wartime novel The Heat of the Day the park appears a number of times, most memorably in a long atmospheric description of the park in an autumn dusk. Regents Park also appears in her short story of wartime London, "Mysterious Kor".

- In Agatha Christie's short story "The Adventure of the Italian Nobleman", Hercule Poirot and Arthur Hastings travel in a taxicab to Regent's Park to investigate a murder that has taken place in "Regent's Court", a fictional block of modern flats nearby.

- In Agatha Christie's novel The Secret Adversary, Tommy Beresford proposes to Prudence "Tuppence" Cowley and Julius Hersheimmer proposes to Jane Finn while in Regent's Park, on their way home from a celebratory dinner for defeating the protagonist of the story, the infamous Mr. Brown.

- Rosamund Stacey, protagonist of Margaret Drabble's novel The Millstone (1965), lives in "a nice flat, on the fourth floor of a large block of an early twentieth-century building, and in very easy reach of Regent's Park".

- Ian Fleming's James Bond novels frequently mention the headquarters of MI6 as a "tall, grey building near Regent's Park."[39]

- In Charlie Higson's post-apocalyptic young adult horror novel The Enemy (2009), a group of children make a perilous trek through an overgrown St. Regent's Park, en route to Buckingham Palace, where they seek safe refuge, after a worldwide sickness has infected adults turning them into something akin to zombies. In the park, diseased monkeys from the nearby zoo attack the group, killing several children and wounding others.

- In Ruth Rendell's crime novel The Keys to the Street (1996), much of the action (and murders) take place in and around Regent's Park.

- In J. K. Rowling's first novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone (1997) and the eponymous film, Harry goes to the London Zoo for his cousin's birthday.

- In Dodie Smith's children's novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians (1956), the protagonist dalmatian dogs live near Regent's Park and are taken there for walks by their human family, the Dearlys. Regent's Park is also featured in the films based on Smith's book.

- The Regent's Park is the setting for several scenes in Virginia Woolf's novel Mrs. Dalloway (1925).

- In Mick Herron's Slough House books, the headquarters of MI5 is referred to as "Regent's Park," even though MI5's real headquarters is adjacent to the Thames, about 2.5 miles from Regent's Park.

In music

edit- In Madness' single "Johnny The Horse" (1999), the eponymous character ends his days in the park after taking "his battered bones and broken dreams to Regent's Park at sunset".

- The artwork to Coil's 1986 album Horse Rotorvator contains a photograph of the bandstand in Regent's Park.

- Bruno Major's song "Regent's Park" is based on the location.

In art

edit- British artist Marion Coutts recreated Regent's, along with Battersea and Hyde Park, as a set of asymmetrical ping-pong tables for her interactive installation Fresh Air (1998–2001)[40]

References

editCitations

- ^ "Westminster Boundary". City of Westminster. 2008. LA 100019597 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Historic England, "Regents Park (1000246)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 10 February 2016

- ^ "The Regent's Park". The Royal Parks. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Mills, A. D. (2004). A Dictionary of London Place-names. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860957-5. OCLC 56654940.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 688.

- ^ "Landscape History". The Royal Parks. Archived from the original on 4 May 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- ^ a b Arnold, Dana. "Burton, Decimus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4125. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h "James Burton [Haliburton], Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50182. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b Arnold, Dana (2005). Rural Urbanism: London Landscapes in the Early 19th Century. Manchester University Press. p. 58.

- ^ Curl, James Stevens (January 2006). "Burton, Decimus". Burton, Decimus (1800–81). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860568-3. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ ODNB, Burton, Decimus (1880–1881)

- ^ Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1580933261.

- ^ "William Copeland Astbury". Facebook. 15 April 2013. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ The Catastrophe in the Regent's Park, The Times, 22 January 1867, p.12

- ^ Wheatley, Henry Benjamin (1891). London, past and present: its history, associations, and traditions – Henry Benjamin Wheatley, Peter Cunningham – Google Books. Archived from the original on 8 July 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ Col ET Vallance (2015). 'Postmen at War – A history of the Army Postal Services from the Middle Ages to 1945' p.110, 114. Stuart Rossiter Trust, Hitchin.

- ^ "Strava | Run and Cycling Tracking on the Social Network for Athletes". Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ "Regent's Park Cyclists – Uniting all of Regent's Parks Cyclists". Regent's Park Cyclists. Archived from the original on 15 February 2018. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ^ UCI wants London Olympic road race route changed Archived 2 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, CyclingWeekly

- ^ Exclusive: 2012 Olympics road race route Archived 13 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, CyclingWeekly

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 327.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 227.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 161.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 122.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 1037.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 208.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 191.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 900.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 382.

- ^ Weinreb et al. 2008, p. 454.

- ^ "MOTCO – Image Database". motco.com. 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ Kenneth Powell (6 November 2002). "Grandeur cannot be done cheaply". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- ^ NGS website[permanent dead link]

- ^ Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- ^ Nairn, Ian (1966). Nairn's London (first ed.). Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0141396156.

- ^ "Tube map" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2017. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ^ "News and Pictures From The 2002 James Bond Celebrity Golf Classic". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Arnaud, Danielle. "Fair Play". Danielle Arnaud. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

Sources

- Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2008). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405-04924-5.

Bibliography

edit- Stourton, James (2012). Great Houses of London. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3366-9.

- Weinreb, B. and Hibbert, C. (ed) (1995) The London Encyclopedia Macmillan ISBN 0-333-57688-8

- Wheatley, Henry Benjamin and Cunningham, Peter "London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, Vol. III"