You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (November 2017) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

The Imperial Regalia, also called Imperial Insignia[citation needed] (in German Reichskleinodien, Reichsinsignien or Reichsschatz), are regalia of the Holy Roman Emperor. The most important parts are the Crown, the Imperial orb, the Imperial sceptre, the Holy Lance and the Imperial Sword. Today they are kept at the Imperial Treasury in the Hofburg palace in Vienna, Austria.

The Imperial Regalia are the only completely preserved regalia from the Middle Ages. During the late Middle Ages, the word Imperial Regalia (Reichskleinodien) had many variations in the Latin language. The regalia were named in Latin: insignia imperialia, regalia insignia, insignia imperalis capellae quae regalia dicuntur and other similar words.

Components

editThe regalia is composed of two different parts. The greater group are the so-called Nürnberger Kleinodien (roughly translated Nuremberg jewels), named after the town of Nuremberg, where the regalia were kept from 1424 to 1796. This part comprised the Imperial Crown, parts of the coronation vestments, the Imperial Orb, the Imperial Sceptre, the Imperial Sword, the Ceremonial Sword, the Imperial Cross, the Holy Lance, and all other reliquaries except St. Stephen's Purse.

St. Stephen's Purse, the Imperial Bible, and the so-called Sabre of Charlemagne were kept in Aachen until 1794, which gave them the name Aachener Kleinodien (Aachen jewels). It is not known how long they have been considered among the Imperial Regalia, nor how long they had been in Aachen.

| Present inventory in Vienna: | |

| Aachen regalia (Aachener Kleinodien) | Probable place of origin, and date of production |

|---|---|

| Imperial Bible (Reichsevangeliar or Krönungsevangeliar) | Aachen, end of 8th century |

| St. Stephen's Purse (Stephansbursa) | Carolingian, 1st third of 9th century |

| Sabre of Charlemagne (Säbel Karl des Großen) | Eastern Europe, 2nd half of 9th century |

| Nuremberg regalia (Nürnberger Kleinodien) | Probable place of origin, and date of production |

|---|---|

| Imperial Crown (Reichskrone) | Western Germany, 2nd half of 10th century |

| Imperial Cross (Reichskreuz) | Western Germany, around 1024/1025 |

| Holy Lance (Heilige Lanze) | Langobardian, 8th/9th century |

| Relics of the True Cross (Kreuzpartikel) | |

| Imperial Sword (Reichsschwert) | Sheath from Germany, 2nd third-part of 11th century |

| Imperial Orb (Reichsapfel) | Western Germany, around end of 12th century |

| Coronation Mantle (Krönungsmantel) (Pluviale) | Palermo, 1133/34 |

| Alb | Palermo, 1181 |

| Dalmatic (Dalmatica or Tunicella) | Palermo, around 1140 |

| Stockings | Palermo, around 1170 |

| Shoes | Palermo, around 1130 or around 1220 |

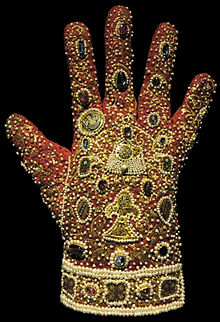

| Gloves | Palermo, 1220 |

| Ceremonial Sword (Zeremonienschwert) | Palermo, 1220 |

| Stole (Stola) | Central Italy, before 1338 |

| Eagle-dalmatic (Adlerdalmatica) | Upper Germany, before 1350 |

| Imperial Sceptre (Zepter) | Germany, 1st half of 14th century |

| Aspergille | Germany, 1st. half of 14th century |

| Reliquary with chains | Rome or Prague, around 1368 |

| Reliquary with a piece of vestment of the John the Evangelist | Rome or Prague, around 1368 |

| Reliquary with a shaving of the Crib of Christ | Rome or Prague, around 1368 |

| Reliquary with an arm-bone of St. Anne | probably Prague after 1350 |

| Reliquary with a tooth of John the Baptist | Bohemia, after 1350 |

| Case (Futteral) of the Imperial Crown | Prague, after 1350 |

| Reliquary with a piece of the tablecloth used during the Last Supper |

History

editMiddle Ages

editThe inventory of the regalia during the late Middle Ages normally consisted only of five to six items. Goffredo da Viterbo counted following items: the Imperial Cross, the Holy Lance, the crown, the sceptre, the orb, and the sword. On other lists, however, the sword is not mentioned.

Whether the medieval chronicles really do refer to the same regalia which are kept in Vienna today depends on a variety of factors. Descriptions of the emperors only spoke of them being "clothed in imperial regalia" without exactly describing which items they were.

The crown can only be dated back to the 13th century, when it is described in a medieval poem. The poem speaks of the Waise (i.e., The Orphan) stone, which was a big and prominent jewel on the front of the crown, probably a white opal with an exceptionally brilliant red fire, since replaced by a triangular blue sapphire. The first definite pictorial image of the crown can only be found later in a mural in the Karlstein Castle close to Prague.

It is also difficult to define for how long the Imperial and Ceremonial Swords have belonged to the regalia.

Whereabouts in medieval times

editUntil the 15th century the Imperial Regalia had no firm depository and sometimes accompanied the ruler on his trips through the empire. Above all with conflicts around the legality of the rule it was important to own the insignia. As depositories during this time some imperial castles or seats of reliable ministerialises are known:

- Limburg Abbey near Dürkheim (Palatinate) (11th century)

- Harzburg (11th century)

- Imperial Palace of Goslar (11th, 13th century)

- Hammerstein Castle (1125)

- Trifels Castle near Annweiler (12th, 13th century, with interruptions)

- Imperial chapel of Haguenau (12th, 13th century, with interruptions)

- Waldburg Castle near Ravensburg (c. 1220–1240)

- Krautheim Castle on the river Jagst (probably 1240–1242)

- Kyburg Palace, today Canton of Zurich in Switzerland (1273–1322, with one interruption)

- Castle Stein, municipality of Rheinfelden in the canton of Aargau in Switzerland (about 1280, under Rudolf of Habsburg)

- Alter Hof (Old Court) in Munich (under Ludwig the Bavarian, 1324–1350)

- St. Vitus Cathedral (Prague) and Karlstein Castle in Bohemia (c. 1350/52–1421)

- Plintenburg and Ofen in Hungary (1421–1424)

Committal to Nuremberg

editEmperor Sigismund transferred the Imperial Regalia "to everlasting preservation" to the Free Imperial City of Nuremberg with a dated document on 29 September 1423. They arrived there on 22 March the following year from Plintenburg, and were kept in the chapel of the Heilig-Geist-Spital. Once a year they were shown to believers in a so-called Heiltumsweisung (worship show), on the fourteenth day after Good Friday. For coronations they were brought to Aachen or Frankfurt Cathedral.

Ceremonial decoration

editSince the Age of Enlightenment at least, the imperial regalia had no constitutive or confirming character for the imperial function any more. It served merely as an adornment for the coronation of the emperors, who all belonged to the House of Habsburg and since the mid-16th century had ceased to be crowned by the pope.

A young Johann Wolfgang Goethe on 3 April 1764, was an eyewitness in Frankfurt during the coronation of the 18-year-old Joseph, Duke of Lorraine to King in Germany. He later wrote dismissively about the event in his autobiography Dichtung und Wahrheit (English: From my Life: Poetry and Truth):

The young king, on the contrary, in his monstrous articles of dress, with the crown-jewels of Charlemagne, dragged himself along as if he had been in a disguise; so that he himself, looking at his father from time to time, could not refrain from laughing. The crown, which it had been necessary to line a great deal, stood out from his head like an overhanging roof. The dalmatica, the stole, well as they had been fitted and taken in by sewing, presented by no means an advantageous appearance. The sceptre and imperial orb excited some admiration; but one would, for the sake of a more princely effect, rather have seen a strong form, suited to the dress, invested and adorned with it.

— J. W. Goethe, Truth and Fiction, Book V[1]

Refuge in Vienna

editWhile French troops were advancing in 1794 in the direction of Aachen during the War of the First Coalition, the pieces located there were brought to the Capuchin's monastery in Paderborn. In July 1796, French troops crossed the Rhine and shortly thereafter reached Franconia. On 23 July the most important parts of the Imperial Regalia (crown, sceptre, orb, eight pieces of the vestments) were hastily evacuated by Nuremberg colonel Johann Georg Haller von Hallerstein from Nuremberg to Regensburg, where they arrived the next day. On 28 September the remaining parts of the jewels were also delivered to Regensburg. Since this elopement parts of the treasure are missing.

Until 1800 the Imperial Regalia remained in the Saint Emmeram's Abbey in Regensburg, from where their transfer began to Vienna on 30 June. The committal there is verified for 29 October. The pieces from Aachen were brought in 1798 to Hildesheim and didn't reach Vienna before 1801.

Nazi and post-war period

editAfter the Anschluss of Austria to the Nazi Reich in 1938 the imperial regalia were returned on instruction by Adolf Hitler to Nuremberg, where they were exhibited in the Katharinenkirche. In the Second World War they were stored for protection from air raids in the Historischer Kunstbunker (English: historical art bunker) beneath Nuremberg Castle.

In 1945 the imperial regalia were recovered by American soldiers, based on an investigation by art historian Lt. Walter Horn,[2] who had joined the US military after becoming a naturalized citizen. In January 1946 the treasures were returned it to the Oesterreichische Nationalbank in allied-occupied Austria. They have been kept permanently in Vienna since that date. The Crown and Regalia were again on display at the Hofburg, the former imperial palace of the Habsburg dynasty, since 1954.[3]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ John Oxenford, ed. (1 May 2004). Autobiography: Truth and Fiction Relating to My Life. J. H. MOORE. Retrieved 22 Feb 2014 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "In Memoriam, 1996, Walter Horn, History of Art: Berkeley". University of California. 20 May 2023.

- ^ Rihoko Ueno (11 Apr 2014). "Recovering Gold and Regalia: a Monuments Man investigates". Archives of American Art. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 13 Apr 2014.

Bibliography

edit- Weltliche und Geistliche Schatzkammer. Bildführer. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. 1987. ISBN 3-7017-0499-6

- Fillitz, Hermann. Die Schatzkammer in Wien: Symbole abendländischen Kaisertums. Vienna, 1986. ISBN 3-7017-0443-0

- Fillitz, Hermann. Die Insignien und Kleinodien des Heiligen Römischen Reiches, 1954.

- Heigl, Peter. The Imperial Regalia in the Nazi Bunker/ Der Reichsschatz im Nazibunker. Nuremberg 2005. ISBN 3-9810269-1-8

- Jason Philip Coy; Benjamin Marschke; David Warren Sabean, eds. (2013). The Holy Roman Empire, Reconsidered. Vol. 1 (Spektrum: Publications of the German Studies Association ed.). Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-7823-8090-0. OCLC 872619479. Retrieved 13 Apr 2014.