Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood[a] is a 2019 comedy-drama film written and directed by Quentin Tarantino. Produced by Columbia Pictures, Bona Film Group, Heyday Films, and Visiona Romantica and distributed by Sony Pictures, it is a co-production between the United States, United Kingdom, and China. It features a large ensemble cast led by Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, and Margot Robbie. Set in 1969 Los Angeles, the film follows a fading actor and his stunt double as they navigate the rapidly changing film industry, with the threat of the Tate murders looming.

| Once Upon a Time...in Hollywood | |

|---|---|

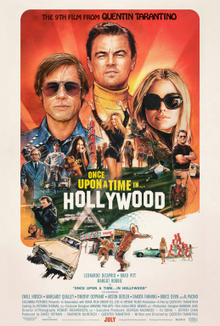

Theatrical release poster designed by Steven Chorney | |

| Directed by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Written by | Quentin Tarantino |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Richardson |

| Edited by | Fred Raskin |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 161 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $90–96 million[3] |

| Box office | $377.6 million[4] |

Announced in July 2017, it is the first Tarantino film not to involve Bob and Harvey Weinstein, as Tarantino ended his partnership with the brothers following the sexual abuse allegations against Harvey Weinstein. After a bidding war, the film was distributed by Sony Pictures, which met Tarantino's demands including final cut privilege. Pitt, DiCaprio, Robbie, Zoë Bell, Kurt Russell, and others joined the cast between January and June 2018. Principal photography lasted from June through November around Los Angeles. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is the final film to feature Luke Perry, who died on March 4, 2019, and it is dedicated to his memory.

Once Upon a Time in Hollywood premiered at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival on May 21, 2019, and was theatrically released in the United States on July 26, 2019, and in the United Kingdom on August 14. It grossed $374 million worldwide and received acclaim from critics; although historical accuracies and artists were criticized. The National Board of Review and the American Film Institute named Once Upon a Time in Hollywood one of the top-ten films of 2019. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was nominated for ten awards at the 92nd Academy Awards, winning two (Best Supporting Actor for Pitt and Best Production Design), and received numerous other accolades. A novelization, written by Tarantino in his debut as an author, was published in 2021.[5]

Plot

editIn February 1969, Hollywood actor Rick Dalton, the former star of the 1950s Western show Bounty Law, copes with a fading career, his most recent roles being guest appearances as TV villains. Agent Marvin Schwarz advises him to make spaghetti Westerns in Italy, which Dalton considers beneath him. Dalton's best friend, stunt double, personal assistant, and driver is Cliff Booth – a World War II veteran, living in a trailer with his pit bull, Brandy. Booth struggles to find stunt work amid rumors he murdered his wife. Meanwhile, Dalton hopes to revive his career by befriending young actress Sharon Tate and her husband, director Roman Polanski, who live next door.

While fixing the TV antenna atop Dalton's roof, Booth notices a hippie man, Charles Manson, arriving at the Polanski residence. Manson says he is looking for music producer Terry Melcher, who once lived there, but Tate's friend Jay Sebring turns him away. While Tate watches herself in The Wrecking Crew at the Fox Bruin Theater, Booth gives a hitchhiker named Pussycat a ride to Spahn Ranch, a former Western film set where Booth did stunt work. Booth checks on George Spahn, the ranch's nearly blind owner, making sure the hippies living there are not exploiting him. After discovering his car's tire has been punctured, Booth physically forces ranch hippie Clem to change it. The hippies' leader Tex is summoned to deal with the situation but arrives as Booth is driving away.

While filming a guest star role as a TV villain on Lancer, Dalton forgets his lines. After berating himself, he returns to set and delivers a performance that impresses his young co-star, Trudi Frazer, and the director, Sam Wanamaker. Meanwhile, Schwarz books Dalton to star in Sergio Corbucci's spaghetti western. Booth accompanies Dalton for the six month shoot in Italy, where Dalton films three additional movies and marries Italian starlet Francesca Capucci. Before returning to the US, Dalton tells Booth that he can no longer afford his salary, which Booth amicably understands.

Returning to Los Angeles on August 8, 1969, Dalton and Booth go out drinking to commemorate their time together. Returning to Dalton's house, Booth smokes an LSD-laced cigarette and takes Brandy for a walk while Dalton makes margaritas. Manson's followers Tex, Sadie, Katie, and FlowerChild arrive to murder the Tate house occupants. Hearing a car's loud muffler, an enraged Dalton orders the group off the private street. Recognizing him, the Family members decide to kill him instead, after Sadie reasons that Hollywood has "taught them to murder". Flowerchild deserts them, speeding off with their car. Breaking into Dalton's house, they confront Capucci and Booth. Booth recognizes them from Spahn Ranch and orders Brandy to attack. Together they kill Tex and injure Sadie, though Booth is stabbed in the thigh and passes out after killing Katie. Sadie stumbles outside, alarming Dalton, who was in his pool, oblivious to the melee inside. Dalton retrieves a flamethrower movie prop from his shed and incinerates Sadie. After Booth is taken away in an ambulance, Sebring and Tate invite Dalton in for a drink.

Cast

edit- Top row, left to right: Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie, Emile Hirsch and Margaret Qualley

- Bottom row: Timothy Olyphant, Austin Butler, Dakota Fanning, Bruce Dern and Al Pacino

- Leonardo DiCaprio as Rick Dalton

- Brad Pitt as Cliff Booth

- Margot Robbie as Sharon Tate

- Emile Hirsch as Jay Sebring

- Margaret Qualley as "Pussycat"

- Timothy Olyphant as James Stacy

- Julia Butters as Trudi Frazer

- Austin Butler as "Tex"

- Dakota Fanning as "Squeaky"

- Bruce Dern as George Spahn

- Mike Moh as Bruce Lee

- Luke Perry as Wayne Maunder

- Damian Lewis as Steve McQueen

- Al Pacino as Marvin Schwarz

- Nicholas Hammond as Sam Wanamaker

- Samantha Robinson as Abigail Folger

- Rafał Zawierucha as Roman Polanski

- Lorenza Izzo as Francesca Capucci

- Costa Ronin as Wojciech Frykowski

- Damon Herriman as Charlie

- Lena Dunham as "Gypsy"

- Madisen Beaty as "Katie"

- Mikey Madison as "Sadie"

- James Landry Hébert as "Clem"

- Maya Hawke as "Flowerchild"

- Victoria Pedretti as "Lulu"

- Sydney Sweeney as "Snake"

- Harley Quinn Smith as "Froggie"

- Kansas Bowling as "Blue"

- Cassidy Vick Hice as "Sundance"

- Danielle Harris as "Angel"

- Rumer Willis as Joanna Pettet

- Dreama Walker as Connie Stevens

- Rebecca Rittenhouse as Michelle Phillips

- Rachel Redleaf as Mama Cass

- Rebecca Gayheart as Billie Booth

- Scoot McNairy as Business Bob Gilbert[6]: page254

- Kurt Russell as Randy Miller and the Narrator

- Zoë Bell as Janet Miller

- Corey Burton as the voice of Bounty Law Promo Announcer

- Michael Madsen as Sheriff Hackett on Bounty Law

- Josephine Valentina Clark as "Happy Cappy"

- Ronnie Zappa as "Tophat"

Quentin Tarantino portrays the director of Dalton's Red Apples cigarettes commercial[7] and the voice of Bounty Law.[8] Musician Toni Basil appears in the opening credits Pan Am scene dancing with Sharon Tate.[9] Margot Robbie also briefly reprises her role as Laura Cameron, a stewardess from the TV series Pan Am. Although her face is not seen, she makes and serves Dalton a cocktail on his flight home from Italy.[10]

Additionally, the film features appearances from Clifton Collins Jr. as Ernesto "The Mexican" Vaquero, a character on Lancer, Omar Doom as Donnie, a biker on Spahn Ranch, Clu Gulager (in his last film role) as a book store owner, Perla Haney-Jardine as an LSD-selling hippie, Martin Kove and James Remar as a Sheriff and "Ugly Owl Hoot", two characters on Bounty Law, Brenda Vaccaro as Schwarz's wife Mary Alice, Tarantino's wife Daniella Pick as Daphna Ben-Cobo, Dalton's co-star in Nebraska Jim, Lew Temple, Vincent Laresca, JLouis Mills, and Maurice Compte as Land Pirates, Gabriela Flores as Maralu the Fiddle Player, and Corey Burton as Bounty Law Promo Announcer (voice).[11] Ex–UFC star Keith Jardine performed stunts on the movie.[12]

An extended cut, released theatrically in October 2019, included an appearance by James Marsden as Burt Reynolds and a voice over by Walton Goggins.[13][14] Danny Strong and Tim Roth shot scenes that were cut. Strong portrayed Dean Martin and Paul Barabuta (based on Rudolph Altobelli), the homeowner of 10050 Cielo Drive, while Roth portrayed Raymond,[6]: page 123 Sebring's English butler.[15][16][17] Sebring had a butler in real life named Amos Russell who was interviewed by the police while investigating the Tate murders.[18] Despite being removed from the final theatrical cut of the film, Roth still received credit for acting in the film.

Character details

editFictional characters

editRick Dalton

edit- Dalton is an actor who starred in the fictitious television Western series Bounty Law from 1959 to 1963,[6]: page11 inspired by real-life series Wanted Dead or Alive, starring Steve McQueen.[19] After Bounty Law, Dalton began to appear in supporting film roles, leading to a four-picture contract with Universal Pictures, ending in 1967. His film career never took off, and in 1967 he started to guest star on TV series as villains.[6]: 10–18

Cliff Booth

edit- Booth, Dalton's stunt double, personal assistant and best friend, is an indestructible World War II hero, specializing in knives and close-quarters combat, and "one of the deadliest guys alive."[20][21] He is a two-time Medal of Honor recipient, and has killed more Japanese soldiers than any other American soldier.[22] Booth first met Dalton during the third season of Bounty Law in 1961 when he was brought in as his stunt double. A month into the job he saved Dalton's life after he caught on fire while filming an episode.[6]: 48–50 Quentin Tarantino and Brad Pitt modeled Booth after Tom Laughlin's portrayal of Billy Jack.[23] Booth had performed stunts on The Born Losers and was paid with the denim outfit worn by Laughlin as Billy Jack, which is what he wears in the film.[6]: 25–26 Booth is inspired by Gary Kent, a stuntman for a film made at the Spahn Ranch while the Manson Family lived there,[24] as well as stuntman, professional wrestler and two-time national judo champion Gene LeBell, who came to work on The Green Hornet after complaints by other stunt performers that Bruce Lee was "kicking the shit out of the stuntmen."[25] Like Booth, LeBell was suspected of murder but never convicted.[26] Pitt channeled Steve McQueen's stunt double Bud Ekins for his portrayal of Booth.[27] Tarantino also revealed that Booth was inspired by a real stuntman who "was the closest equivalent to Stuntman Mike" (Kurt Russell) from Death Proof. He was "absolutely indestructible ... scared everybody ... [and] killed his wife on a boat and got away with it."[28]

- Billie Booth is Cliff's wife, whose death in the film—and the ambiguity surrounding it—is a reference to Natalie Wood's,[29] as is Billie's sister's name, Natalie.[30] Unlike the ambiguity of the film, in the novelization Cliff did in fact murder Billie.[31][32] He shot her with a speargun, almost tearing her in half, which he immediately regretted.[22] There is a connection between Cliff and Robert Blake, to whom Tarantino dedicates the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood novel.[33] Also in the novelization, Cliff had murdered three other people, including another stuntman.[6]: 72–73, 268

Other fictional characters

edit- Trudi Frazer (Julia Butters), the precocious child actor who portrays Mirabella on Lancer, is inspired by Jodie Foster,[34]: 1:20:00–1:22:00 while Mirabella is inspired by the character Teresa O'Brien from said series, portrayed by Elizabeth Baur. The character is older in the real-life Lancer.[35][36] Frazer goes on to become an Academy Award–nominated actress. Her third nomination is for Tarantino's 1999 remake of The Lady in Red.[6]: 353–54

- Marvin Schwarz of the William Morris Agency[6]: page1 is Dalton's agent, a role that Tarantino wrote specifically for Al Pacino.[37]

- Francesca Capucci the Italian starlet who marries Dalton is based on 1960s Italian actresses and sex symbols, namely Sophia Loren, Claudia Cardinale, Virna Lisi and Monica Vitti.[38][39]

- Some characters, such as Zoë Bell's stunt coordinator Janet Lloyd and Heba Thorisdottir's makeup artist Sonya, were portrayed by individuals who performed the same jobs for the film.[40][41]

- Randy Lloyd is the stunt coordinator for The Green Hornet,[29] a position that was held by Bennie Dobbins on the series in real life.[25][42]

- Michael Madsen's Sheriff Hackett on Bounty Law is partially inspired by Peter Breck,[43] who also served as Madsen's inspiration for Joe Gage in Tarantino's The Hateful Eight; specifically Breck's role in The Big Valley.[44]

- Martin Kove's inspiration for his Sheriff on Bounty Law was Henry Fonda's portrayal of Wyatt Earp in John Ford's 1946 film My Darling Clementine.[45] In casting Kove, Madsen, and James Remar for Bounty Law, Tarantino said he cast genre character actors of today to mirror character actors of the 1950s and 1960s who would appear on TV Westerns, such as Claude Akins and Vic Morrow.[43]

Historical characters

edit- Sharon Tate was an actress married to film director Roman Polanski, and is Dalton's neighbor in the film. Margot Robbie did not consult Polanski about playing Tate, but read his 1984 autobiography Roman by Polanski in preparation for the role.[46] Tate filmed her last movie, The Thirteen Chairs, in Italy in 1969 during her pregnancy,[47] at the same time as Dalton films movies there in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.[39]

- Roman Polanski, a film director whose credits include Rosemary's Baby and The Fearless Vampire Killers, where he first met Tate.[48]

- Jay Sebring was a celebrity hairstylist, Tate's friend and ex-boyfriend, and friend of Bruce Lee (whom he helped get started in Hollywood) and Steve McQueen.[38][49] Sebring and Tate attended a party at Cass Elliot's house which Charles Manson also attended.[50]

- Abigail Folger, heir to the Folgers coffee fortune, and her boyfriend Wojciech Frykowski were Tate's friends.[51]

- James Stacy was an actor who played Johnny Madrid Lancer on Lancer.[52][53] Stacy is last shown in the film leaving the Lancer set on a motorcycle; Stacy was in a motorcycle accident in 1973 that resulted in the death of his passenger and the loss of his arm and leg. His ex-wife, actress Connie Stevens, also portrayed in the film, organized a fundraiser for his recovery.[54][38]

- Wayne Maunder, who portrayed Scott Lancer on Lancer,[52][53] died during the filming of the movie while Luke Perry, who plays him in his last film role, died shortly afterwards.[55] Luke's son Jack Perry appears with him in the film.[56]

- Sam Wanamaker directed the real pilot of Lancer, as he does in the film. The Land Pirates were characters in the real pilot,[53] who also appear in the pilot within the film.[2] Wanamaker led the restoration of William Shakespeare's Globe Theatre after moving to London while blacklisted from Hollywood in the 1950s.[52] In the film he likens Rick Dalton's character on Lancer to Shakespeare's Hamlet.[38] In a deleted scene Wanamaker says, "You'd be amazed how many Westerns the plot is Shakespearean." He goes on to try to convince Dalton to play his character as Edmund from Shakespeare's King Lear.[57]

- Business Bob Gilbert (Scoot McNairy) is a character on Lancer being portrayed by Bruce Dern.[6]: page254 (McNairy is playing Dern, playing Business Bob)

- Bruce Lee was an actor and martial artist who starred as Kato on The Green Hornet. He taught Tate martial arts for The Wrecking Crew and also trained Sebring, Polanski and McQueen.[49]

- Steve McQueen was an actor and friend of Tate, Sebring, and Lee.[49] On the night of the Tate murders, Sebring invited McQueen over to Tate's house, but his date wanted to stay in.[51] After the murders, the police found a Manson Family hit list including McQueen's name.[51]

- Mama Cass Elliot and Michelle Phillips were members of the folk band the Mamas & the Papas. The sheet music for their song "Straight Shooter" was found on the piano at the murder scene in the Tate–Polanski residence. The song is also used in the film and teaser trailer.[58][59] Polanski had an affair with Phillips while he was married to Tate. After the Tate murders, Polanski suspected Michelle's husband, John Phillips of the killings out of revenge for the affair.[58]

- Connie (Monica Staggs) and Curt (Mark Warrack)[2] are horse-riding customers at Spahn Ranch. As one way of earning their keep, the Manson Family gave horse riding tours to people visiting the ranch.[60] Tarantino stated that he thinks his mother and step-father (Connie and Curt) took him horse riding at Spahn Ranch when he was six years old.[61]

- Perla Haney-Jardine's hippie girl, who sells the acid-dipped cigarette to Cliff Booth, is based on "Today" Louise Malone, a hippie who appears in the 1968 documentary Revolution.[62][63] As in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, she sells the acid cigarettes at a traffic light. Tarantino said the dialogue in the scene is taken from the documentary.[62]

- Allen Kincade (Spencer Garrett) is a celebrity television interviewer who is based on Wink Martindale. The character was named Wink Martindale in the screenplay but changed to Allen Kincade shortly before shooting due to clearance issues.[64]

- The bookseller at Larry Edmunds Bookshop being portrayed by Clu Gulager who sells a copy of Tess of the d'Urbervilles to Sharon Tate is Milton Luboviski, who was the real-life proprietor.[65][66][67]

- Harvey "Humble Harve" Miller, portrayed by Rage Stewart,[68] was a Los Angeles KHJ Boss Radio DJ who was convicted of killing his wife.[69]

- The TV show Hullabaloo Rick Dalton appears on in the film was a real-life show, and one of the go-go dancers portrayed is Lada St. Edmund, who went on to become the highest paid stuntwoman in Hollywood history.[38]

The Manson Family

edit- George Spahn was an 80-year-old nearly blind man who rented his ranch out for westerns. The Manson Family lived on the ranch.[70]

- Charlie is Charles Manson, a convicted felon and cult leader of "the Family" (later dubbed "the Manson Family" by the media), a hippie commune based in California. Members of the Family committed nine murders in the summer of 1969.[71] Damon Herriman, who portrays Manson, also portrays him in David Fincher's Netflix series Mindhunter.[72] Tarantino revealed that, since the Tate murders never happen in the Once Upon a Time in Hollywood universe, neither do the LaBianca murders. The Manson Family gets kicked off Spahn Ranch and splits up, with Manson never becoming a familiar name or cult figure.[73]

- "Pussycat", aka Debra Jo Hillhouse,[6]: page81 is a composite character, with her nickname based on Kathryn Lutesinger's "Kitty Kat", yet modeled after and most notably based on Ruth Ann Moorehouse.[60][74] Manson frequently sent Moorehouse into the city to lure men with money back to Spahn Ranch.[60] Lutesinger met Manson through her boyfriend, Bobby Beausoleil.[75] There was a Manson Family member named Pussycat, who is mentioned by Ed Sanders in his book The Family: The Story of Charles Manson's Dune Buggy Attack Battalion; according to those interviewed, Pussycat underwent an exorcism with Manson present. The real identity of Pussycat is never revealed.[76] She is also an homage to Myra (Laurie Heineman) from John G. Avildsen's Save the Tiger.[11]

- "Squeaky" was Lynette Fromme's nickname, given to her by Spahn because of the sound she made when he touched her.[77] She was Spahn's main caretaker, tending to his needs, sexual or otherwise.[60]

- "Tex" was Charles Watson's nickname. Spahn gave it to him because of his Texas accent.[78] Within the film's universe the police later theorize that Tex, Sadie, and Katie broke into Rick Dalton's house because they "were frying on acid and were out to perform a Satanic ritual," based on Cliff Booth telling them that Tex said he was "the Devil".[6]: page111

- "Sadie" was Susan Atkins' nickname. Manson gave everyone fake IDs, and the name on Atkins' was "Sadie Mae Glutz".[77] Atkins was called "Sexy Sadie" after a track on the Beatles' self-titled album that some of the Family members may have believed was about her.[71]: 241, 252, xv Mikey Madison, who played Sadie, would later portray a similar character in the 2022 film Scream. Like Sadie, her character Amber Freeman is a knife-wielding psycho killer. Amber decides to murder based on films whereas Sadie does so based on TV. Sadie gets set on fire by Rick Dalton, while Amber is set ablaze by Gale Weathers (Courteney Cox).[79][80]

- "Katie" was Patricia Krenwinkel's nickname because of the name on her fake ID.[77] Madisen Beaty, who portrays Krenwinkel, previously portrayed her on the TV series Aquarius.[81]

- "Flowerchild" is the movie's name for Linda Kasabian, the fourth Family member to go to Tate's house.[80] In 1970, Kasabian was described as a "true flower child".[82]

- "Snake" was Dianne Lake's nickname, given to her by Manson because she rolled around in grass pretending to be a snake. At 14 she became the youngest member of the Manson Family after being kicked off Wavy Gravy's Hog Farm. Her parents were associates of Manson and her mother had dropped acid with him before Lake joined them.[83]

- "Blue" was Sandra Good's nickname. Manson told her, "Woman, you're earth. I'm naming you Blue. Fix the air and the water. It's your job."[77] Kansas Bowling, the actress who plays her, appears in the film with her sister Parker Love Bowling, who plays Family member "Tadpole". Parker previously portrayed a Manson girl in a reenactment for the Canadian History Channel.[84]

- "Gypsy" was Catherine Share's nickname, which she gave herself after meeting a man named Gypsy, with whom she shared a birthday and believed him to be her cosmic twin.[77]

- "Happy Cappy" is based on Catherine Gillies, who was nicknamed "Capistrano" by Spahn because she grew up in San Juan Capistrano and was later shortened to "Cappy" by the Family.[85][86] Josephine Valentina Clark, the actress who plays her, added the "Happy" while working on the character.[85]

- "Lulu" was one of Leslie Van Houten's nicknames, and "Clem" one of Steve Grogan's.[60]

- "Tophat", portrayed in the film by Ronnie Zappa,[87] was an alias of Bobby Beausoleil. In his 2001 book Turn Off Your Mind, Gary Lachman mentions that, "Beausoleil had a style; a top hat that set him apart from the usual hippie fare."[88] Beausoleil wrote: "I spied a felt top hat in the window of a... shop... I couldn't afford (it)... but it felt like it had been made for me... I couldn't resist the temptation to buy it." Beausoleil claimed that as soon as he put on the hat, ideas floating in his head came together.[89]

- The character of "Sundance" was named by Cassidy Vick Hice, the actress who portrays her. She wrote, "I was asked to name my character by Quentin himself."[90]

- Straight Satan David, portrayed in the film by David Steen,[2] is a member of the Straight Satans Motorcycle Club, associates of the Family. Manson attempted to recruit them as personal security but, with the exception of club treasurer Danny DeCarlo, was unsuccessful. DeCarlo lived on the ranch as part of the Family.[71]: 77, 89, 102

- Bill "Sweet William" Fritsch, portrayed by Tom Hartig[68] was a member of the Hells Angels and Diggers and a Manson Family associate. Fritsch worked security for the Altamont Free Concert and acted in deleted scenes of Kenneth Anger's Lucifer Rising.[91]

Production

editWriting and development

editThe screenplay for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was developed slowly over several years by Quentin Tarantino. While he knew he wanted it to be titled Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, evoking the idea of a fairy tale, he publicly referred to the project as Magnum opus.[92] The life of the work for the first five years was as a novel,[92] which Tarantino considered to be an exploratory approach to the story, not yet having decided if it would be a screenplay. Tarantino tried other writing approaches: the early scene between Rick Dalton and Marvin Schwarz was originally written as a one-act play.[93]

Tarantino discovered the centerpiece for the work about 10 years previously while filming Death Proof with Kurt Russell who had been working with the same stunt double, John Casino, for several years. Even though there was only a small bit for Casino to do, Tarantino was asked to use him, and agreed. The relationship fascinated Tarantino and inspired him to make a film about Hollywood.[94][95] Tarantino stated, while Casino may have been a perfect double for Russell years earlier, when he met them, "this was maybe the last or second-to-last thing they'd be doing together".[93]

Tarantino first created stuntman Cliff Booth, giving him a massive backstory. Next, he created actor Rick Dalton for whom Booth would stunt double. Tarantino decided to have them be Sharon Tate's next-door neighbors in 1969. The first plot point he developed was the ending, moving backwards from there, this being the first time Tarantino had worked this way. He thought of doing an Elmore Leonard-type story, but realized he was confident enough in his characters to let them drive the film and let it be a day in the life of Booth, Dalton, and Tate. He would use sequences from Dalton's films for the action, inspired by Richard Rush's 1980 film The Stunt Man, which used the scenes from the WWI movie they were making within the film as the action.[96] Further, to get his mind into Dalton, Tarantino wrote five episodes of the fictional television show Bounty Law, in which Dalton had starred, having become fascinated with the amount of story crammed into half-hour episodes of 1950s western shows.[16]

Tarantino kept the only copy of the third act of the script in a safe to prevent it from being prematurely released.[97] DiCaprio, Robbie, and Pitt were the only other people who read the entire script.[98][16] In an interview with Adam Sandler, Pitt revealed that the only other copy of the script was burned by Tarantino.[99]

Pre-production and casting

editOn July 11, 2017, it was reported that Tarantino's next film would be about the Manson murders. Harvey and Bob Weinstein would be involved,[100] but it was not known whether The Weinstein Company would distribute the film, as Tarantino sought to cast before sending a package to studios.[citation needed] Tarantino approached Brad Pitt and Jennifer Lawrence for roles and Margot Robbie was being considered for the role of Sharon Tate.[101]

After the Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse allegations, Tarantino cut ties with Weinstein and sought a new distributor, after having worked with Weinstein for his entire career. At this point, Leonardo DiCaprio was revealed to be among a short list of actors Tarantino was considering.[102] A short time later, reports circulated that studios were bidding for the film, and that David Heyman had joined as a producer, along with Tarantino and Shannon McIntosh.[103]

On November 11, 2017, Sony Pictures announced they would distribute the film, beating Warner Bros., Universal Pictures, Paramount Pictures, Annapurna Pictures and Lionsgate.[104] Tarantino's demands included a $95 million budget, final cut privilege, "extraordinary creative controls", 25% of first-dollar gross, and the stipulation that the rights revert to him after 10 to 20 years.[105]

In January 2018, DiCaprio signed on, taking a pay cut to collaborate with Tarantino again.[106][107] Al Pacino was being considered for a role.[108] On February 28, 2018, the film was titled Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, with Pitt cast as Cliff Booth.[109] DiCaprio and Pitt were each paid $10 million.[110] In March 2018, Robbie, who had expressed interest in working with Tarantino,[111] signed to co-star as Sharon Tate,[112] while Zoë Bell confirmed she would appear.[113] In May 2018, Tim Roth, Kurt Russell, and Michael Madsen joined the cast.[114] Timothy Olyphant was also cast.[115] In June 2018, Damian Lewis, Luke Perry, Emile Hirsch, Dakota Fanning, Clifton Collins Jr., Keith Jefferson, Nicholas Hammond, Pacino, and Scoot McNairy joined the cast.[116][117][118] Spencer Garrett, James Remar, and Mike Moh were announced in July.[119] In August 2018, Damon Herriman as Charles Manson, and Lena Dunham, Austin Butler, Danny Strong, Rafał Zawierucha, Rumer Willis, Dreama Walker, and Margaret Qualley were cast.[120][121][122]

When Butler auditioned for the film, he was not aware of which character he was being considered for. Tarantino told him it was for a villain or a hero on Lancer, when in fact it was for Tex Watson. To prepare for her audition, Maya Hawke practiced with her father, Ethan Hawke. She stated, "He (Tarantino) actually organized a really amazing callback process that was unlike anything I've ever been through... except maybe auditioning for drama school." Willis auditioned for two roles, neither of which she got, but was later offered the part of Joanna Pettet. Sydney Sweeney said everyone she auditioned with did so for the same character, then were told they could do extra credit. Some did artwork, and she wrote a letter in character. Julia Butters says her sitcom American Housewife was on while Tarantino was writing her character, Trudi Frazer. He looked up and said, "Maybe she can try this."[123]

Burt Reynolds was cast as George Spahn in May 2018, but died in September before he was able to film his scenes and was replaced by Bruce Dern.[114][70] Reynolds did a rehearsal and script reading, his last performance. After reading the script and learning that Pitt would be portraying Booth, Reynolds told Tarantino, "You gotta have somebody say, 'You're pretty for a stunt guy.'" The line appears in the film, spoken to Booth by Bruce Lee.[124] The last thing Reynolds did before he died was run lines with his assistant for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.[125]

Tarantino initially approached Jennifer Lawrence to portray Manson Family member Squeaky Fromme, saying "She was interested but something just didn't work out."[100][126] Tarantino had also spoken to Tom Cruise about playing Cliff Booth, who was being considered for the role.[103][127] Charlie Day was offered to audition for the part of Manson. Day did not show up to audition because he did not want to see himself in that role.[128] Macaulay Culkin auditioned for an undisclosed role. It was his first audition in eight years.[129] It was also initially reported that frequent Tarantino collaborator Samuel L. Jackson was in talks for a role as the villain of a Bounty Law episode.[101]

Filming and design

editWhen it came to the look of 1969 Hollywood in the film a large part of it was told through the memory of a child. Tarantino stated:

the jumping off point was going to be my memory – as a six-year old sitting in the passenger seat of my stepfather's Karmann Ghia. And even that shot, that kind of looks up at Cliff as he drives by the Earl Scheib, and all those signs, that's pretty much my perspective, being a little kid...[28]

Principal photography began on June 18, 2018, in Los Angeles, California, and wrapped on November 1, 2018.[130] Tarantino's directive was to turn Los Angeles of 2018 into Los Angeles of 1969 without computer-generated imagery.[66] For this, he tapped into previous collaborators for production: editor Fred Raskin, cinematographer Robert Richardson, sound editor Wylie Stateman and makeup artist Heba Thorisdottir. He also brought first-time collaborators, production designer Barbara Ling, based on her work recreating historical settings in The Doors, and costume designer Arianne Phillips.[131] Despite Tarantino's intent, the production wound up using more than 75 digital visual effects shots by Luma Pictures and Lola VFX, mainly to cover up modern billboards and erasing non-1960s buildings from driving shots.[132]

To film at the Pussycat Theater, production designer Barbara Ling and her team covered the building's LED signage and reattached the theater's iconic logo, rebuilding the letters and neon. Ling said the lettering on every marquee in the film is historically accurate. To restore Larry Edmunds Bookshop, she reproduced the original storefront sign and tracked down period-appropriate merchandise, even recreating book covers. Her team restored the Bruin and Fox Village theaters, including their marquees, and the storefronts around them. Stan's Donuts, across the street from the Bruin, got a complete makeover.[66]

The Playboy Mansion scene was shot at the actual mansion.[133] Tarantino was adamant about filming there, but it took a while to obtain permission since the mansion had been sold to a private owner following Hugh Hefner's death. Tarantino and Ling met with the new owner to discuss the parts they wanted to use, but he was reluctant since the property was in the middle of a renovation. After long negotiations he agreed, and Ling was able to dress the vacant mansion, front courtyard, and backyard for the party scene, evoking as much of the 1960s appearance of the mansion as possible.[133] The dance sequence for the scene was choreographed by Toni Basil who knew Sharon Tate and once dated Jay Sebring.[9] She also choreographed Dalton's Hullabaloo scene.[9] Though the film is set in 1969, the mansion was actually not acquired by Playboy until 1971, resulting in an obvious anachronism.

Several important scenes were shot at the Musso & Frank Grill, which was a "must have" location for Tarantino according to Rick Schuler, supervising location manager. "I feel so lucky that there's a place like the Musso & Frank Grill, one that exists now exactly how it has always been," Tarantino said. "It was fantastic being able to shoot at an iconic landmark that is so authentic and connected to Hollywood."[134]

The scenes involving the Tate–Polanski house were not filmed at Cielo Drive, the winding street where the 3,200 square-foot house once stood. The house was razed in 1994 and replaced with a mansion nearly six times the size. Scenes involving the house were filmed at three different locations around Los Angeles: one for the interior, one for the exterior, and a Universal City location for the scenes depicting the iconic cul-de-sac driveway.[135]

Movie poster artist Steven Chorney created the poster for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood as a reference to The Mod Squad.[136] He and Renato Casaro created the posters for the movies within the film, Nebraska Jim, Operation Dyn-O-Mite, Uccidimi Subito Ringo Disse il Gringo, Hell-Fire Texas, and Comanche Uprising, which was reprinted for Dalton's home parking spot.[136] Mad magazine caricaturist Tom Richmond created the covers of Mad and TV Guide featuring Dalton's Jake Cahill modeled after the art of Jack Davis.[137]

Tarantino told Richardson, "I want [it] to feel retro but I want [it] to be contemporary." Richardson shot in Kodak 35mm with Panavision cameras and lenses, in order to weave time periods. For Bounty Law they shot in black and white, and brief sequences in Super 8 and 16mm Ektachrome. In the film, Lancer was shot on a retrofitted Western Street backlot at Universal Studios, designed by Ling. Richardson crossed Lancer with Alias Smith and Jones for the retro-future look Tarantino wanted. The way they filmed Lancer was not possible in 1969, but Tarantino wanted his personal touch on it. Richardson said that filming the movie touched him personally: "The film speaks to all of us... We are all fragile beings with a limited time to achieve whatever it is we desire... that at any moment that place will shift... so take stock in life and have the courage to believe in yourself."[133][138] In order to build the Lancer set Ling watched "Enormous amounts of episodes" of the series. She built a western town filled with adobe buildings. For Bounty Law, she went for a dusty, dirty, early Deadwood look, to separate it from the "Moneyed Lancer world".[133]

Spahn Ranch was recreated in detail over about a three-month period.[133] A wildfire completely destroyed the ranch in 1970 so the scenes for the movie were filmed at nearby Corriganville Movie Ranch in Simi Valley, which was also a movie ranch at one time.[139] Tarantino made sure to use a lot of dogs in the scenes. He said in real life many dogs lived on the ranch and made it feel alive. He even made sure there were dogs moving around in every shot. He was inspired to use the dogs in this manner from the way Francis Ford Coppola used helicopters in Apocalypse Now during the Robert Duvall scenes.[140]

To improve the use of practical effects, Leonardo DiCaprio was allowed to light stunt coordinators on fire while shooting scenes with a flamethrower.[141] The exterior of the Van Nuys Drive-in theater scene was filmed at the Paramount Drive-in theater since the Van Nuys Drive-in theater no longer exists.[142] As the camera rises up over the theater, the shot transitions to a miniature set with toy cars.[143]: 36:00–39:00 For some of the driving scenes, the Hollywood Freeway and Marina Freeway in Los Angeles were shut down for hours in order to fill them with vintage cars.[144] The scene depicting Bruce Lee training Jay Sebring was filmed at Sebring's actual house.[28]

The scene in which Rick Dalton flubs his lines in Lancer was not in the screenplay but rather an idea DiCaprio had on set while filming. Afterwards Tarantino came up with the idea for Dalton's "freakout" scene in his trailer, taking inspiration from Robert De Niro's performance in Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver. Tarantino stated, "It's got to be like Travis Bickle when he's in his apartment by himself." DiCaprio improvised the entire scene.[145]

Music

editThe soundtrack from the film is a compilation album of classic rock, which includes multiple tracks from Paul Revere & the Raiders, as well as 1960s radio ads and DJ patter. The film also contains numerous songs and scores not included on the soundtrack, including from artists the Mamas & the Papas and Elmer Bernstein.[146][59]

Release

editOnce Upon a Time in Hollywood premiered at the Cannes Film Festival on May 21, 2019, the 25th anniversary of Tarantino's premiere of Pulp Fiction at the festival.[147] It was released theatrically in the United States on July 26, 2019, by Sony Pictures Releasing under its Columbia Pictures label.[148] The film was originally scheduled for release on August 9, 2019, to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Tate–LaBianca murders.[148]

A teaser trailer was released on March 20, 2019, featuring 1960s music by the Mamas and the Papas ("Straight Shooter") and by Los Bravos ("Bring a Little Lovin'").[149] The official trailer was released on May 21, 2019, featuring the songs "Good Thing" by Paul Revere & the Raiders, and "Brother Love's Travelling Salvation Show" by Neil Diamond.[150] The studio spent around $110 million marketing the film.[3] An extended cut of the film featuring four additional scenes was released in theaters on October 25, 2019.[151]

Home media

editThe film was released through digital retailers on November 22, 2019, and on Blu-ray, 4K Ultra HD, and DVD on December 10. The 4K version is available as a regular version and a collector's edition.[152] In April 2020, Media Play News magazine announced Once Upon a Time in Hollywood earned Title of the Year and Best Theatrical Home release in the 10th annual Home Media Awards.[153] Both the DVD and Blu-ray contain a deleted scene, in which Charles Manson confronts Paul Barabuta, portrayed by Danny Strong, the homeowner and caretaker of the Tate-Polanski residence. Barabuta is based on the home's owner, Rudolph Altobelli, and its caretaker, William Garretson.[17][154]

Reception

editBox office

editOnce Upon a Time in Hollywood grossed $142.5 million in the United States and Canada, and $232.1 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $374.6 million.[4] By some estimates, the film needed to gross around $250 million worldwide in order to break-even,[155] with others estimating it would need to make $400 million in order to turn a profit.[156]

In the United States and Canada, the film was projected to gross $30–40 million from 3,659 theaters in its opening weekend, with some projections having it as high as $50 million or as low as $25 million.[157][158] The week of its release, Fandango reported the film was the highest pre-seller of any Tarantino film.[159] The film made $16.9 million on its first day, including $5.8 million from Thursday night previews (the highest total of Tarantino's career). It went on to debut to $41.1 million, finishing second behind holdover The Lion King and marking Tarantino's largest opening. Comscore reported that 47% of audience members went to see the film because of who the director was (compared to the typical 7%) and 37% went because of the cast (compared to normally 18%).[3] The film grossed $20 million in its second weekend, representing a "nice" drop of just 51% and finishing third, and then made $11.6 million and $7.6 million the subsequent weekends.[160][161][162] In its fifth weekend the film made $5 million, bringing its running domestic total to $123.1 million, becoming the second-highest of Tarantino's career behind Django Unchained.[163] In its ninth weekend, its global total earnings reached $329.4 million, surpassing Inglourious Basterds to become Tarantino's second-highest global grosser behind Django Unchained.[164]

Critical response

editOn the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 86% of 584 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Thrillingly unrestrained yet solidly crafted, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood tempers Tarantino's provocative impulses with the clarity of a mature filmmaker's vision."[165] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 84 out of 100, based on 62 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[166] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave it an average grade of "B" on an A+ to F scale, while those at PostTrak gave it an average of 4 out of 5 stars and a 58% "definite recommend".[3]

The Hollywood Reporter said critics had "an overall positive view", with some calling it "Tarantino's love letter to '60s L.A.," praising its cast and setting, while others were "divided on its ending."[167] ReelViews' James Berardinelli awarded the film 3.5 stars out of 4, saying it was "made by a movie-lover for movie-lovers. And even those who don't qualify may still enjoy the hell out of it."[168] RogerEbert.com's Brian Tallerico gave it four out of four stars, calling it "layered and ambitious, the product of a confident filmmaker working with collaborators completely in tune with his vision".[169] The Chicago Sun-Times, Richard Roeper described it as "a brilliant and sometimes outrageously fantastic mash-up of real-life events and characters with pure fiction", giving it full marks.[170]

Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian gave it five out of five stars, praising Pitt and DiCaprio's performances and calling it "Tarantino's dazzling LA redemption song".[171] Steve Pond of TheWrap said: "Big, brash, ridiculous, too long, and in the end invigorating, the film is a grand playground for its director to fetishize old pop culture and bring his gleeful perversity to the craft of moviemaking."[172] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone awarded the film 4.5 out of 5 stars, remarking that "All the actors, in roles large and small, bring their A games to the film. Two hours and 40 minutes can feel long for some. I wouldn't change a frame."[173] Katie Rife of The A.V. Club gave it a B+, noting "The relationship between Rick and Cliff is at the emotional heart of Once Upon A Time... In Hollywood" and calling it Tarantino's "wistful midlife crisis movie".[174]

In Little White Lies, Christopher Hooton described it as "occasionally tedious" but "constantly awe-inspiring", noting it did not seem to be a "love letter to Hollywood" but an "obituary for a moment in culture that looks unlikely to ever be resurrected."[175] Writing for Variety, Owen Gleiberman called it a "heady engrossing collage of a film—but not, in the end, a masterpiece."[176]

Richard Brody of The New Yorker called it an "obscenely regressive vision of the sixties" that "celebrates white-male stardom (and behind-the-scenes command) at the expense of everyone else."[177] Caspar Salmon of The Guardian took issue with the violence in the film, writing, "Tarantino's filmography reveals a director in search of increasingly gruesome settings to validate his revenge fantasies and...blood-thirst."[178]

Accolades

editAt the 92nd Academy Awards, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood received nominations for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Original Screenplay, Best Cinematography, Best Costume Design, Best Sound Editing, and Best Sound Mixing; and won Best Supporting Actor and Best Production Design.[179] The film's other nominations include ten British Academy Film Awards (winning one),[180] twelve Critics' Choice Movie Awards (winning four),[181] and five Golden Globe Awards (winning three).[182] The National Board of Review included the film as one of the top 10 films of the year and awarded Tarantino Best Director and Pitt Best Supporting Actor.[183] The American Film Institute included it as one of the top 10 films of 2019.[184] In December 2021, the film's screenplay was listed number twenty-two on the Writers Guild of America's "101 Greatest Screenplays of the 21st Century (So Far)".[185]

Analysis

editStory, themes and character symbolism

editDan Schindel of Hyperallergic wrote of the symbolism in the film's nostalgia. He wrote the detail is almost "microscopic", in its use of "hundreds of period ephemera" across various mediums, most of which is unrecognizable to most viewers. Schindel writes that these forgotten memories surround the character of Rick Dalton because he too is a piece of forgotten nostalgia. Schindel also writes about the dynamics between the characters. Dalton and Booth represent the duality of attitudes towards "their seeming impending obsolesce." Booth being relaxed and accepting it and Dalton being fragile and insecure about it. Critic Raphael Abraham extends this view, noting that Tarantino’s use of nostalgia in the film reaches beyond character to reimagine history itself. By turning the tragic Manson murders into a kind of fairytale, Tarantino uses revisionist storytelling to create a "joyride" through the darker moments of Hollywood’s past, allowing characters like Dalton to find symbolic redemption amid the backdrop of a reimagined 1969.[186]As Dalton's whole life is about how he is perceived, he is obsessed with how he wishes to be perceived. Sharon Tate, also an actor, is filled with joy when she is able to see herself entertain a theater audience. But, Schindel says, that scene also humanizes her, making her a person, rather than the "victim" she has become. He also expresses that Dalton and Booth represent Old Hollywood, while Tate represents New Hollywood and the future. Schindel states that Tarantino uses darkness, both for Booth and his questionable past as well as in the Manson Family. While Booth's possible crimes shade the nostalgia, the Manson clan shades the future. In the end, however, not only are Booth and Dalton able to save the future, but Dalton becomes the hero he always wanted to be.[187]

Travis Woods also wrote of what the three characters represent and how it is demonstrated in the film. He states that the three leads represent the past, present, and future. Dalton is the past, stuck in a fading world and afraid to let go. Booth is the present, always living in the moment, and Tate the promise of a future on the rise. They also represent three class levels of Hollywood with Booth literally living in the shadows of the movie industry. His home is a trailer in the shadows of the Van Nuys Drive-In Theater. Woods also construes how Booth being the stunt double of Dalton is illustrated throughout. Dalton struggles with an emotional arc and change, while Booth clashes with danger and physical obstacles. Woods points out the actor's job is to provide the audience with the emotional arc, while the stuntman's job is to step in for the physicality and danger, as told to us in the first scene. This is shown when Dalton faces his existential fears on the set of Lancer by taking on a new acting challenge on a Western set and overcoming his fears and inner struggles. Meanwhile, Booth comes in to handle the dangerous stuff on another Western set where he also triumphs. While they both have their victories, Tate has hers as well by not only simply living her life but also by watching herself in a movie with an audience. Woods writes the finale ties it all together; "How a stunt works, and fantasy is made real: the actor performs a scene all the way up to a threat of violence. There's a cut, and the stunt double enters the scene, stands in for the actor and cheats death." And so, Dalton fearlessly confronts the would-be killers outside of his home. After a cut, "Booth enters the scene... cheats death," and handles the physical danger. At the end, Dalton re-enters and gets the glory. A feat that could not have been achieved by either the actor or stuntman alone, but only together. Woods concludes, this also represents the past and present "uniting to allow for a better future". "The past leads to the present, and the present leads to the future, and all three are required for the narrative to continue."[188]

David G. Hughes wrote of the symbolized fantasy. He noted that Tate is a "symbol of effervescent life, unadulterated joy, and graceful innocence,"[189] while Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune saw the character as a Goddess.[190] However Hughes was much more interested in what Booth represents. He wrote how Dalton's stress and psychological issues prevent him from being a symbol of fantasy for the audience. Booth is the film's hero and simultaneously works loyally for Dalton from a place of low social standing. Hughes states this could be "a Marxist point about invisible labor and the Substructure." However, Hughes feels this does not work to engage the audience. He draws on Sigmund Freud and his Psychopathic Characters on the Stage. He says what makes Booth interesting and particularly Brad Pitt's portrayal of him is sex appeal. Being handsome, strong, loyal, and courageous makes him desirable. Hughes states that Booth is Laura Mulvey's "...perfect, ...complete, more powerful ideal ego." Tarantino has Booth fight Bruce Lee to create the myth of Booth. Hughes also writes that Booth embodies the Buddha's teachings on Zen, but also that he is capable of "barbaric violence". These qualities make him the "fantasy of righteous male power". Hughes compares Booth to Charles Manson, saying both are violent outcasts who sit between the worlds of Western Renaissance and Eastern philosophy. However, he says they are the antithesis of each other. While Booth has a code, Manson only serves himself. Manson "is Hollywood's monster from the id [and Booth] is its ego ideal and savior."[189] A Los Angeles Catholic bishop, Robert Barron, praised the character of Cliff Booth as embodying the four cardinal virtues.[191]

Naomi Fry of The New Yorker wrote how the film is about the disposability of people in Hollywood. She sees Dalton and Tate as needing to be seen as their livelihoods depend on it and "an actor onscreen as a conduit for [their] own fantasies and those of others." Dalton feels he is no longer able to do this, and is tortured by the feeling. Booth has also been discarded by Hollywood to the point of Dalton having to beg for him to be used. Fry says of Dalton's career that there is "a sense of the ruthlessness of Hollywood, whose denizens are devastated when the industry almost inevitably turns away its gaze." She also notes how Tarantino "pulls a neat trick by casting DiCaprio and Pitt," two of the biggest movie stars as a has-been and a nobody.[192]

Armond White and Kyle Smith of National Review, in separate reviews, interpreted and praised the film as being politically conservative, with Smith writing that "It mercilessly sends up leftist values. In its foundations, it's so breathtakingly right-wing it could have been made by Mel Gibson."[193][194]

The finale and the Manson Family

editTheologian David Bentley Hart wrote that Once Upon a Time "exhibit[s] a genuine ethical pathos" for its portrayal of "cosmic justice". Hart wrote how he was a child when the Tate murders occurred and that the Manson Family were "the first monsters who ever truly terrified me and tormented me with nightmares." He remembers how the children at his school would tell the stories of the Manson Family murders. Hart praised the revisionism when "Tarantino's version of the story unexpectedly veered away into some other, dreamlike, better world, where the monsters inadvertently passed through the wrong door and met the end they deserved." Hart states "the artistic masterstroke" comes in the end when Tate is heard "as a disembodied voice... speaking from that alternative reality, that terrestrial paradise that evil could not enter."[195]

Av Sinensky wrote about the ending of the film when Susan Atkins concludes that the Manson Family members should kill Dalton because he played a character who killed people on TV, he "taught them to kill." Sinensky notes that Tarantino is putting "the words of his critics into the mouth of a Manson murderer," regarding his use of fictional gratuitous violence.[196] While David G. Hughes opined that Tarantino is using the scene to say that those who crusade against fictional violence are hypocrites and complicit in real violence. Hughes wrote that by switching the real-life violence by Manson Family members with movie violence instead directed at them, "Tarantino is making a firm distinction between cruel real-world violence and ethical, cathartic fantasy violence."[189]

Priscilla Page wrote how the Manson Family murders have become a myth and "framed our understanding of what was happening in America and the world," and in the film Spahn Ranch represents the intersection of Hollywood fantasy "and the dark underbelly of Los Angeles."[197] Michael Phillips likened the Manson girls to "strung out Sirens,"[190] while Page stated how the Manson Family "are ghosts haunting Spahn Ranch... Demons to be exorcised." Page notes how the final act accomplishes this exorcism and also the symbolism of Booth and Tex Watson pointing guns at each other. Watson's is real, just as the Manson Family's violence was. Booth's is not but rather a finger, as his violence is fictional. Through the fictional violence the myth of the Manson Family is purged. She writes the exorcism and revenge of the film are not only through the violence but also because "the film denies Manson a meaningful presence," demythologizing him and "reduc[ing] him to a cameo, expos[ing] the Manson Family as inept, and mak[ing] Sharon Tate the story's beating heart."[197]

Steven Boone referred to Dalton going to Tate's house as "entering the gates of Cielo Drive's Hollywood heaven." Something his colleague Simon Abrams also alluded to when he commented, "Jay Sebring invites [Dalton] in for a drink like a hipper St. Peter."[198] Dan Schindel also saw Dalton's walk up Tate's driveway as "an ascent to heaven", based on the "rising camera movement".[187] Naomi Fry compared Dalton going through the gates as him entering the Garden of Eden.[192]

Writing in the academic journal Animation, Jason Barker draws from Aristotle's Poetics to analyze in detail the film's use of "cartoon violence", speculating that such violence "is more or less inversely related to the film's dramatic content". Barker concludes that: "Through self-indulgent, inane, insane and tyrannical cartoonism, Once Upon a Time. . . in Hollywood presents not so much a measure of contemporary violence, as a measure of indifference to violence: dramatic indifference and, perhaps, social indifference to a cartoon violence that is real in more ways than one."[199]

Booth's fantasy

editMultiple critics interpreted Cliff Booth as an unreliable narrator when it came to him remembering his fight with Bruce Lee. "In the span of seconds" the fight "goes from being viewed by dozens of people to absolutely no one." The crowd just disappears which some believe shows the flashback to be a "false memory". The interpretation is that Booth is only remembering what he wants to and "the purpose of that scene is to show us we can't trust Cliff."[200][201]

Steven Hyden of Uproxx interpreted the ending of the film as a vision of Cliff Booth brought on through his consumption of LSD. Hyden proposes that when Booth smokes the acid-cigarette and says, "And away we go," it marks the beginning of his vision. He then leaves to take his dog Brandy for a walk, walking by the car of killers down the street who Hyden believes Booth sees in the car and recognizes from Spahn Ranch. This allows Booth's imagination to run wild thanks to the acid. He imagines the killers in the car talking about his and Dalton's show, Bounty Law. He then imagines a scenario that lets him play out his violent fantasies and allows Dalton to be a hero, using a flamethrower from a film he would never actually still own but which occupies a place in Booth's memory. Hyden writes that the ending is Booth's hallucinatory fantasy that allows him to stay employed by Dalton, while also allowing Dalton to be accepted by the New Hollywood elite, Sharon Tate. Also that in this fantasy Tate and members of the Manson Family are fans of Dalton, just as Booth is.[202]

Steven Boone of The Hollywood Reporter also commented on the ending feeling like Booth's fantasy. About the ending, he wrote "It's as if stuntman Cliff, a serene Hollywood foot soldier...was the editor here."[198] Kyle Anderson theorized the ending is not only Booth's fantasy but Dalton's as well. He states that Booth's memory of fighting Lee is "his twisted recollection of an event that probably didn't happen." Anderson notes that "Cliff is a complete psychopath" whose life has amounted to menial labor, while "Rick [is] a washed-up loser." The ending is not "just a dream of what might have happened," it is Booth's and Dalton's dream. Booth gets to fulfill his hero fantasy and instead of Dalton losing his house and career he gets to be idolized and accepted by the "cool kids".[203]

Billie Booth

editAnna Swanson wrote about the death of Billie and how it is used to frame the rest of the film. She writes how Tarantino not showing us what happens is a deliberate decision and also an homage to the death of Marvin (Phil LaMarr) in Pulp Fiction and the fact we do not know why Vincent Vega's (John Travolta) gun goes off and shoots Marvin. Within the film one can interpret Billie's death as Cliff's speargun accidentally going off in the same vein as Vincent's gun, or as a cold-blooded murder by Cliff and a cover up, or in a number of other scenarios. Swanson argues that which interpretation the individual viewer has will lead them to view the rest of the film through that lens and have a completely different experience than someone who views it alternatively. She notes we do not even know whose perspective the Billie Booth scene is from. It is a flashback within a flashback and so could be Cliff's memory but as it is told by Randy it could be his perspective based on what he heard. It could be what Cliff is imagining Randy is saying to Rick. It could even be an "omniscient perspective". If one views Cliff as innocent it makes him easier to like, and could be "suggesting an innocent man's life can be ruined by unfortunate circumstances beyond his control." However, if one views Cliff as guilty, "It's a depiction of the extent to which someone can literally get away with murder." In referencing the ending of the film, Swanson asks if Cliff is guilty, "Are we supposed to forgive one death he caused because of the lives he saved?" Swanson concludes that another purpose of the scene is to build up the theme of "Hollywood mythology". Referring to the scene's allusion to Natalie Wood, she writes "the myths last, while the truth is lost in an ocean vaster than the rolling neon streets of the Hollywood of yore."[30]

Lindsey Romain says the scene is "a Rorschach Test for the audience". She argues that how the viewer interprets the scene changes the interpretation of the ending of the film. If Cliff murdered Billie then he is despicable and the killings he commits at the end are self-serving. However, if he is innocent then he is a hero. Romain writes "either read is accurate, and both feel purposeful." By leaving Billie's death open-ended, Romain believes Tarantino is asking, "Is Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood a touching fable about reclaiming relevance, or a horror story about a business that forgives heinous acts the second righteousness is procured?" Romain concludes that "maybe it's both," and "about art...about violence and how we participate in and consume it."[204]

Red Apple ad

editWriting for The Washington Post, Sonny Bunch commented on the mid-credits Red Apple cigarettes advertisement scene. He believes it is a commentary of current filmmaking and a "pitch-perfect parody of the films that have dominated box office charts in recent history." Bunch compares the fake ad to the real ones used as mid-credit scenes in the DC, Marvel, and Fast & Furious franchises. The scenes in those films are used to advertise the next film in their franchise. He also notes how those ads tie their franchises' universes together just as Red Apple does with the Tarantino universe.[205]

Cultural references

editThe title is a reference to director Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West and Once Upon a Time in America.[206] On the poster of Dalton's film Red Blood Red Skin, inspired by Land Raiders, he appears with Telly Savalas. The posters for the two films are the same, except with Dalton replacing George Maharis.[207] The movie Voytek Frykowski is watching is Teenage Monster, presented by horror host Seymour.[208]

Archive footage from many films is included in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, including C.C. and Company, Lady in Cement, Three in the Attic, and The Wrecking Crew, in which Sharon Tate appears as Freya Carlson.[209] Three scenes were digitally altered, replacing the original actors with Rick Dalton. One from an episode of The F.B.I., entitled "All the Streets Are Silent", in which Dalton appears as the character portrayed by Burt Reynolds in the actual episode.[206] Another from Death on the Run, with Dalton's face imposed over Ty Hardin's.[207] The third is from The Great Escape, with Dalton appearing as Virgil Hilts, the role made famous by Steve McQueen.[206] For The 14 Fists of McCluskey, a World War II film-within-the-film starring Dalton, footage and music from Hell River is used.[210]

Connections to other Tarantino films

editCliff Booth is a reference to Brad Pitt's character in Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds, Lt. Aldo Raine, a special forces WWII veteran who takes the cover of a stuntman.[206] One of Rick Dalton's Italian films in the movie is directed by real-life director Antonio Margheriti. Antonio Margheriti is also used as an alias for Sgt. Donny Donowitz (Eli Roth) in Inglourious Basterds.[206] The scene involving Dalton playing a character who burns Nazis with a flamethrower is similar to the ending of Inglourious Basterds, which ends with Nazi leadership being burned to death.[206][211]

The final scene features Dalton in a commercial for fictional Red Apple cigarettes, which appear in many Tarantino films.[211] Additionally another common Tarantino brand Big Kahuna Burger is advertised on a billboard.[206] When Dalton and Booth get back from Italy they walk by the blue mosaic wall in LAX, the same wall that the title character in Tarantino's Jackie Brown (Pam Grier) moves past in the opening credits of that film.[212] The characters of stunt coordinator husband and wife, Randy (Kurt Russell) and Janet Lloyd (Zoë Bell) are an homage to characters in Tarantino's Death Proof; Stuntman Mike McKay (Russell) and Zoë Bell who plays herself, a stunt woman.[29]

In the film, Bruce Lee engages in a fight with Cliff Booth on the set of The Green Hornet.[212][213] The Green Hornet theme song is featured in Tarantino's Kill Bill: Volume 1.[212] The masks worn by the Crazy 88 gang in that film are the same as Lee's mask as Kato in The Green Hornet.[214] The car Booth drives is a 1964 blue Volkswagen Karmann Ghia convertible. It is the same year, color, make and model of the car that Beatrix "the Bride" Kiddo (Uma Thurman) drives in Kill Bill: Volume 2.[29] Similarly, Rick Dalton's 1966 Cadillac de Ville is the same car driven by Mr. Blonde (Michael Madsen) in Reservoir Dogs. It was owned by Madsen.[215][216]

Historical accuracy and influence

editIn a scene, Sharon Tate goes into Larry Edmunds Bookshop and purchases a copy of Tess of the d'Urbervilles.[29] In real life, Tate gave a copy to Roman Polanski shortly before her death. In 1978 Polanski directed the film adaptation, Tess (1979), dedicating it to Tate.[29]

Tate and Polanski's Yorkie Terrier in the film is named "Dr. Sapirstein",[29] as was Tate's Yorkie in real life, named after the doctor portrayed by Ralph Bellamy in Rosemary's Baby.[217] The carrier she puts the dog in is the one that Tate actually owned.[217]

In the film, Tate goes to see The Wrecking Crew at the Fox Bruin Theater. She convinces the theater's employees that she stars in the movie after they fail to recognize her. Tarantino stated the scene came from a personal experience. When True Romance was released, he saw it at the same theater, where he eventually convinced its employees that he wrote the script.[144]: 39:00–42:00 The outfit Margot Robbie wears in the scene is based on the one Tate wore in Eye of the Devil.[29]

On the set of Batman, for a crossover episode with The Green Hornet,[218] a fight was scripted with Kato (Bruce Lee) losing to Dick Grayson's Robin (Burt Ward). When Lee received the script, he refused to do it, so it was changed to a draw. When the cameras rolled, Lee stalked Ward until Ward backed away. Lee laughed and told him he was "lucky it is a TV show."[219] Stuntman Gene LeBell carried Lee around in a Fireman's Carry when he first arrived on The Green Hornet set in response to Lee being tough on stuntmen.[220] In the film, stuntman Cliff Booth fights Lee on the set of The Green Hornet; the fight ends in a draw. Booth refers to Lee as "Kato".[213]

According to Rudolph Altobelli, who rented the house to Polanski and Tate, in March 1969, Charles Manson showed up. Polanski's friend, Iranian photographer Shahrokh Hatami (who directed the short documentary Mia and Roman) also said he saw Manson enter the grounds. Hatami approached Manson, asking him what he wanted. He told Hatami he was looking for Terry Melcher. Hatami responded the house was the Polanski residence and perhaps Melcher lived in the guest house. Altobelli told Manson that Melcher no longer lived there.[221] This happens in the film, with Jay Sebring in place of Altobelli and Hatami.[222]

On the night of August 8, 1969, Patricia Krenwinkel, Tex Watson, and Susan Atkins broke into Tate's house, murdering her and four others.[71]: 176–180 In the film, they go to Tate's house to commit the murders but instead end up breaking into Dalton's house after he interrupts them.[80] Linda Kasabian went along that night, though she did not murder anyone and stayed outside the whole time as a lookout. In the film, she goes along and does not murder anyone but takes off and does not stay.[80] Watson told his victims, "I'm the Devil, and I'm here to do the Devil's business." In the film, he says it to Cliff Booth.[223]

In the film, Atkins convinces the others to seek revenge by killing Rick Dalton, star of a TV western. Since TV taught them to kill, it is fitting they kill the guy from TV, and "My idea is to kill the people who taught us to kill!"[80][224] In real life, Manson Family member Nancy Pitman said: "We are what you have made us. We were brought up on your TV. We were brought up watching Gunsmoke and Have Gun – Will Travel."[225] Sandra Good said: "You want to talk about devils and demonic and immorals and evil, go to Hollywood. We don't touch the evil of that world. We don't even skim it."[226] In the film when the four Manson Family members who drive to Tate's house are sitting outside in their car, Rick Dalton comes out of his house and yells at them to leave. In real-life the four members stopped at the house of Rudolf Weber, down the street from Tate's house. Weber came out and yelled at them to leave. Weber told the police he was tired of hippies on his street.[227]

Clem Grogan was convicted of the murder of stuntman Donald Shea on Spahn Ranch, whom he repeatedly beat with a lead pipe.[228] In the film, Grogan is instead beaten by stuntman Cliff Booth.[229] The 1959 Ford Galaxie driven by the Manson Family is a detailed replica of the car used in the Tate–LaBianca murders. Car coordinator Steven Butcher found the actual car, but after a meeting with Tarantino, they decided using it would be "too creepy".[215] Boeing 747s are used in several airliner scenes, but were not in commercial use until 1970;[230] the film is set in 1969.[231]

Character controversies

editBruce Lee

editThe film's depiction of Bruce Lee drew criticism. In the film, Lee is asked on a film set whether he could defeat Muhammad Ali in a fight, to which he responds that he would "make him a cripple". Cliff responds with laughter, causing Lee to challenge him to a fight. Although Lee initially kicks Cliff to the ground, Cliff manages to throw Lee into the side of a car. Fans and contemporaries of Lee, including his protégé Dan Inosanto, criticized the portrayal.[232][233] Lee's daughter Shannon described the depiction as "an arrogant asshole who was full of hot air" and that "they didn't need to treat him in the way White Hollywood did when he was alive."[233] Lee's student and friend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar,[234] who starred with Lee in Game of Death, stated that Tarantino's portrayal of Lee was "sloppy and somewhat racist".[235]

Mike Moh, who played Lee, said he was conflicted at first: "Bruce in my mind was literally a God. [He] didn't always have the most affection for stuntmen; he didn't respect all of them."[236] He stated, "Tarantino loves Bruce Lee; he reveres him."[237] Brad Pitt and stunt coordinator Robert Alonzo objected to an extended version of the fight in which Lee loses.[238] According to Lee's friend and The Green Hornet stuntman Gene LeBell, Lee had a reputation for "kicking the shit out of the stuntmen. They couldn't convince him that he could go easy and it would still look great on film."[25] In the 2018 Bruce Lee: A Life, Lee's biographer Matthew Polly wrote, Lee would jump-kick people on the set. According to Lee's co-star Van Williams, it stopped when "He dislocated [a set designer's] jaw." Polly continued, "Bruce insisted on close quarters combat. The stuntmen hated it." Williams said, "[The stuntmen] ... didn't want to work on the show. They were tired of getting hurt." LeBell was tasked with "calming Bruce down."[220] According to Williams, Lee's treatment of stuntmen drove the show's stunt coordinator Bennie Dobbins to want to fight [him].[42]

Tarantino responded, saying Lee was "kind of an arrogant guy," and that Lee's widow, Linda, wrote in her 1975 book Bruce Lee: The Man Only I Knew that he could beat Muhammad Ali.[239] She wrote, "Even the most scathing critics admitted that Bruce's Gung fu was sensational. One critic wrote, 'Those who watched him would bet on Lee to render Cassius Clay (Ali) senseless if they were put in a room and told anything goes.'"[240] In 1972, Lee himself stated: "Everybody says I must fight Ali some day. ... Look at my hand. That's a little Chinese hand. He'd kill me."[241]

Shannon filed a complaint with the China Film Administration affecting the film's release in China unless alterations were made. After Tarantino refused to remove the scene, China cancelled the release of the film on October 18, 2019, one week before its release date there.[242]

Sharon Tate

editAfter being contacted over concerns, Tarantino invited a representative of Roman Polanski, Sharon Tate's widower, over to his house to read the script and report back to Polanski, to assure him "he didn't have anything to worry about". Tarantino stated: "When it comes to Polanski, we're talking about a tragedy that would be unfathomable for most human beings," and that he did not contact him while writing it, as he did not want to cause him anxiety. Despite this, Polanski's wife, Emmanuelle Seigner, criticized Tarantino for using Polanski's likeness after the film's premiere.[243]

Debra Tate, Sharon's sister, initially opposed the film, saying it was exploitative and perpetuated mistruths: "To celebrate the killers and the darkest portion of society as being sexy or acceptable in any way, shape or form is just perpetuating the worst of our society." After Tarantino contacted her and showed her the script, she withdrew her opposition, saying: "This movie is not what people would expect it to be when you combine the Tarantino and Manson names." She felt that Tarantino was a "very stand-up guy"; after visiting the set, she was impressed by Robbie and lent her some of Sharon's jewelry and perfume to wear in the film.[244]

After the premiere, journalist Farah Nayeri asked Tarantino why Robbie had so few lines. Tarantino responded, "I reject your hypothesis." Robbie elaborated, "I think the moments on screen show those wonderful sides of [Tate] could be adequately done without speaking."[245] Tarantino said, "I thought it would both be touching and pleasurable and also sad and melancholy to just spend a little time with [Tate], just existing... I wanted you to see Sharon a lot."[16]

Manson Family

editCharles Manson was convicted of the murders of Tate and four others, despite not being present, due mostly to a theory presented by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi that Manson was trying to instigate an apocalyptic race war, leaving only Black Muslims[71]: 246 and the Family. According to the theory, the Black Muslims[71]: 246 would eventually look to Manson to lead them. According to members of the Family – Paul Watkins, Juan Flynn and Barbara Hoyt – Manson referred to the race war as Helter Skelter, getting the name from the song of the same name.[71]: 244–247, 334, 361–362 [246]

Musician and filmmaker Boots Riley criticized Tarantino's film for not portraying Bugliosi's Helter Skelter narrative, or depicting the Family as white supremacists,[247] as did Lorraine Ali of the Los Angeles Times, in which she wrote that portraying the Manson Family as hippies is "a more bankable image than Manson the ignorant white supremacist."[72]

However, according to members of The Family – Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten, Patricia Krenwinkel, Catherine Share, and Ruth Ann Moorehouse – the Tate murders were not perpetrated to start Helter Skelter, but as copycat murders mirroring that of Gary Hinman, in an attempt to convince police the killer was still at large,[71]: 426–435 and get Bobby Beausoleil released from jail, as he was charged with Hinman's murder. He stated the murders had nothing to do with race.[248]

According to Jay Sebring's protégé and business partner Jim Markham, who provided original Sebring hair products for Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, the murders were instigated by a drug deal gone bad, not a race war. He believes Manson was at Tate's house the day before the murders to sell drugs to Sebring and Voytek Frykowski, which resulted in the two beating Manson up.[249] In his interview with Truman Capote, Beausoleil said, "They burned people on dope deals. Sharon Tate and that gang."[250]

On The Joe Rogan Experience, Tarantino said he thought Bugliosi's theory was "bullshit". He believes Manson never sent anyone over to Tate's house to murder anyone, and that the murders happened spontaneously.[251]

Related projects

editNovels

editOnce Upon a Time in Hollywood

editIn November 2020, Tarantino signed a two-book deal with HarperCollins. On June 29, 2021, he published his first novel, an adaptation of Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.[252] The audiobook is narrated by Jennifer Jason Leigh who previously starred in Tarantino's The Hateful Eight.[5] According to Tarantino, her Hateful Eight character Daisy Domergue was "A Manson girl out west, like Susan Atkins or something."[253]

According to Tarantino, the novel is "a complete rethinking of the entire story," and adds details to various sequences and characters, including multiple chapters dedicated to the backstory of Cliff Booth.[254] The novel also departs from the film, the film's finale occurs towards the beginning of the novel, and its aftermath includes Rick Dalton earning newfound fame as a regular on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.[22] It also focuses on Charles Manson's pursuit of a music career,[22] the "inner worlds" of Sharon Tate and Trudi Frazer,[255] and has a whole chapter focused on actor Aldo Ray.[6]: 337–349

The Films of Rick Dalton

editIn June 2021, Tarantino revealed he wrote and plans to publish a second novel connected to Once Upon a Time in Hollywood about the films of Rick Dalton.[34]: 45:00–47:00 The book details every film and TV series of Dalton's entire career, some of which are completely fictional but the majority of Dalton's work are real, with Dalton replacing the actors who actually starred in the films.[34]: 46:00–48:00 In it, Cliff Booth writes a film for Dalton featuring a flamethrower, which they produce and Dalton directs.[34]: 47:00–49:00

Film and television

editExtended cut