San Leandro (Spanish for "St. Leander") is a city in Alameda County, California, United States. It is located in the East Bay of the San Francisco Bay Area; between Oakland to the northwest, and Ashland, Castro Valley, and Hayward to the southeast. The population was 91,008 as of the 2020 census.[12]

San Leandro, California | |

|---|---|

| City of San Leandro | |

Clockwise, from top: San Leandro City Hall, Peralta Home, Casa Peralta | |

| Nickname(s): SL, The 'Dro[citation needed] | |

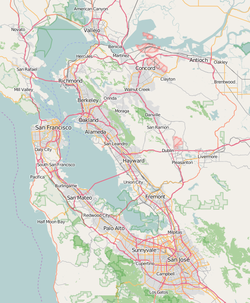

Location within Alameda County | |

| Coordinates: 37°43′30″N 122°09′22″W / 37.72500°N 122.15611°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Alameda |

| Region | San Francisco Bay Area |

| Incorporated | March 21, 1872[1] |

| Named for | St. Leander of Seville[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–Manager[3] |

| • Mayor[9] | Juan González III |

| • Council members by district number[9] |

|

| • City manager | Janelle Cameron[4][5] |

| • State Legislators | Asm. Mia Bonta (D)[6] Sen. Nancy Skinner (D)[7] |

| • U.S. Representative | Barbara Lee (D)[8] |

| Area | |

• Total | 15.52 sq mi (40.19 km2) |

| • Land | 13.32 sq mi (34.51 km2) |

| • Water | 2.19 sq mi (5.68 km2) 14.81% |

| Elevation | 56 ft (17 m) |

| Population | |

• Total | 91,008 |

| • Rank | 97th in California |

| • Density | 5,900/sq mi (2,300/km2) |

| Demonym | San Leandran[13] |

| Time zone | UTC–8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC–7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 94577–94579 |

| Area code(s) | 510, 341 |

| FIPS code | 06-68084 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 232427, 1659582, 2411794 |

| Website | www |

History

editPrehistory

editThe first inhabitants of the geographic region that would eventually become San Leandro were the ancestors of the Ohlone people, who arrived sometime between 3500 and 2500 BC.[citation needed]

Spanish and Mexican eras

editThe Spanish settlers called these natives Costeños, or 'coast people,' and the English-speaking settlers called them Costanoans. San Leandro was first visited by Europeans on March 20, 1772, by Spanish soldier Captain Pedro Fages and the Spanish Catholic priest Father Crespi.

San Leandro is located on the Rancho San Leandro and Rancho San Antonio Mexican land grants. Its name refers to Leander of Seville, a sixth-century Spanish bishop.[2] Both land grants were located along El Camino Viejo, modern 14th Street / State Route 185.

The smaller land grant, Rancho San Leandro, of approximately 9,000 acres (3,600 ha), was given to José Joaquín Estudillo in 1842. The larger, Rancho San Antonio, of approximately 44,000 acres (18,000 ha), was given to another Spanish soldier, Don Luis Maria Peralta, in 1820. Beginning in 1855, two of Estudillo's sons-in-law, John B. Ward and William Heath Davis, laid out the townsite that would become San Leandro, bounded by the San Leandro Creek on the north, Watkins Street on the east, Castro Street on the south, and on the west by the longitude lying a block west of Alvarado Street.[15][16] The city has a historical Portuguese American population dating from the 1880s, when Portuguese laborers from Hawaii or from the Azores began settling in the city and established farms and businesses. By the 1910 census, they had accounted for nearly two-thirds of San Leandro's population.[17]

American era

editIn 1856, San Leandro became the county seat of Alameda County, but the county courthouse was destroyed there by the devastating 1868 quake on the Hayward Fault. The county seat was then re-established in the town of Brooklyn (now part of Oakland) in 1872.

During the American Civil War, San Leandro and its neighbor, Brooklyn, fielded a California militia company, the Brooklyn Guard.

San Leandro was one of a number of suburban cities built in the post–World War II era of California to have restrictive covenants, which barred property owners in the city from selling properties to African Americans and other minorities. As a result of the covenant, In 1960, the city was almost entirely white (99.3%), while its neighbor city of Oakland had a large African American population.[18] The United States Supreme Court, in Shelley v. Kraemer, later declared such covenants unenforceable by the state. San Leandro was an 86.4% white-non-Hispanic community according in the 1970 census.[18] The city's demographics began to diversify in the 1980s.[19] By 2010, Asian Americans had become a plurality population in San Leandro, with approximately one-third of the population, with non-Hispanic Whites accounting for 27.1% of the population.[20]

Geography and geology

editThe San Leandro Hills run above the city to the northeast. In the lower elevations of the city, an upper regionally contained aquifer is located 50 to 100 feet (15 to 30 m) below the surface. At least one deeper aquifer exists approximately 250 feet (75 m) below the surface. Some salt water intrusion has taken place in the San Leandro Cone. Shallow groundwater generally flows to the west, from the foothills toward San Francisco Bay. Shallow groundwater is contaminated in many of the locales of the lower elevation of the city. Contamination by gasoline, volatile organic compounds and some heavy metals has been recorded in a number of these lower-elevation areas.[21][22]

The trace of the Hayward Fault passes under Foothill Boulevard in San Leandro. Follow the link in the reference to see a series of photos of the fault cutting the asphalt between 1979 and 1987.[23]

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 426 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,369 | 221.4% | |

| 1900 | 2,253 | — | |

| 1910 | 3,471 | 54.1% | |

| 1920 | 5,703 | 64.3% | |

| 1930 | 11,455 | 100.9% | |

| 1940 | 14,601 | 27.5% | |

| 1950 | 27,542 | 88.6% | |

| 1960 | 65,962 | 139.5% | |

| 1970 | 68,698 | 4.1% | |

| 1980 | 63,952 | −6.9% | |

| 1990 | 68,223 | 6.7% | |

| 2000 | 79,452 | 16.5% | |

| 2010 | 84,950 | 6.9% | |

| 2020 | 91,008 | 7.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[24] | |||

2020

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[25] | Pop 2010[26] | Pop 2020[27] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 33,646 | 23,006 | 17,865 | 42.35% | 27.08% | 19.63% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 7,622 | 10,052 | 9,708 | 9.59% | 11.83% | 10.67% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 360 | 246 | 224 | 0.45% | 0.29% | 0.25% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 18,064 | 24,924 | 32,365 | 22.74% | 29.34% | 35.56% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 627 | 596 | 712 | 0.79% | 0.70% | 0.78% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 175 | 198 | 440 | 0.22% | 0.23% | 0.48% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 3,019 | 2,691 | 3,713 | 3.80% | 3.17% | 4.08% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 15,939 | 23,237 | 25,981 | 20.06% | 27.35% | 28.55% |

| Total | 79,452 | 84,950 | 91,008 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010

editThe 2010 United States Census[28] reported that San Leandro had a population of 84,950. The population density was 5,423.8 inhabitants per square mile (2,094.1/km2). The racial makeup of San Leandro was 31,946 (37.6%) White, 10,437 (12.3%) African American, 669 (0.8%) Native American, 25,206 (29.7%) Asian, 642 (0.8%) Pacific Islander, 11,295 (13.3%) from other races, and 4,755 (5.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 23,237 persons (27.4%). Non-Hispanic Whites numbered 20,004 (23.5%).

The Census reported that 84,300 people (99.2% of the population) lived in households, 282 (0.3%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 368 (0.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 30,717 households, out of which 10,503 (34.2%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 14,142 (46.0%) were married couples, 4,509 (14.7%) had a female householder with no husband present, 1,863 (6.1%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 1,706 (5.6%) unmarried couples, and 326 (1.1%) same-sex couples. 8,228 households (26.8%) were made up of individuals, and 3,128 (10.2%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.74. There were 20,514 families (66.8% of all households); the average family size was 3.36.

The population was spread out, with 18,975 people (22.3%) under the age of 18, 7,044 people (8.3%) aged 18 to 24, 23,469 people (27.6%) aged 25 to 44, 23,779 people (28.0%) aged 45 to 64, and 11,683 people (13.8%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.3 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.5 males.

There were 32,419 housing units at an average density of 2,069.9 per square mile (799.2/km2), of which 30,717 were occupied, of which 17,667 (57.5%) were owner-occupied, and 13,050 (42.5%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 1.4%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.8%. 50,669 people (59.6% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 33,631 people (39.6%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

editAccording to the 2000 census,[29] there were 30,642 households, out of which 28.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.1% were married couples living together, 12.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.3% were non-families. 28.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average

In the city, the population was spread out, with 22.2% under the age of 18, 7.8% from 18 to 24, 32.0% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 16.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 93.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.4 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $51,081, and the median income for a family was $60,266. Males had a median income of $41,157 versus $33,486 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,895. About 4.5% of families and 6.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 7.3% of those under age 18 and 6.5% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

editSan Leandro has long been home to many food-processing operations, and is home to many corporate businesses, such as Ghirardelli, OSIsoft, 21st Amendment Brewery, Begier Buick, and a Coca-Cola plant. Maxwell House operated a coffee roasting plant, where the Yuban brand was produced from 1949 until 2015, when it was closed as part of a cost-cutting plan instituted by parent company Kraft Foods.[30] The city has five major shopping centers: the Bayfair Center, Westgate Center, Greenhouse Shopping Center,[31] Marina Square Center,[32] and Pelton Plaza.[33] Lucky's flagship store opened in San Leandro.

Under San Leandro Mayor Stephen H. Cassidy, the city set the goal in 2012 of "becoming a new center of innovation in the San Francisco Bay Area."[34] San Leandro came "out of the downturn like few places around, attracting tech startups, artists and brewers to a onetime traditional industrial hub."[35]

In January 2011, Cassidy and Dr. J. Patrick Kennedy, a San Leandro resident and the president and founder of OSIsoft, one of the city's largest employers, "began developing the public-private partnership that would become Lit San Leandro,"[36] a high speed, fiber optic broadband network. In October 2011, the city approved the license agreement that allowed the installation of the fiber-optic cables in the existing conduits under San Leandro streets.[37] In 2012, San Leandro was awarded a $2.1 million grant from the U.S. Economic Development Administration to add 7.5 miles to the network.[38] By 2014, the network expansion was completed, bringing the total length of fiber in the city to over 18 miles.[39] The network is capable of transmitting at up to 10 Gbit/s and is currently only available to business users.[40]

The Zero Net Energy Center, which opened in 2013,[41] is a 46,000-square-foot (4,300 m2) electrician training facility created by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 595 and the Northern California chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association. Training includes energy-efficient construction methods, while the facility itself operates as a zero-energy building.[42][43]

According to the San Leandro's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[44] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | San Leandro Unified School District | 1,380 |

| 2 | Kaiser Permanente Medical Group | 1,032 |

| 3 | City of San Leandro | 582 |

| 4 | Ghirardelli Chocolate Company | 487 |

| 5 | San Leandro Hospital | 460 |

| 6 | OSIsoft LLC | 364 |

| 7 | Costco Wholesale | 358 |

| 8 | BCI Coca-Cola Bottling Co. | 325 |

| 9 | Wal-Mart Store 2648 | 323 |

| 10 | Paramedics Plus LLC | 295 |

Education

editSan Leandro is home to two school districts: The San Lorenzo Unified School District includes parts of Washington Manor and the San Leandro Unified School District includes most of San Leandro, plus a small part of Oakland.[45] The board of the San Leandro Unified School District is composed of Melissa Fegurgur (Area 1), Jackie C. Perl (Area 2), Evelyn Gonzalez (Area 3), Leo Sheridan (Area 4), Diana J. Prola (Area 5), James Aguilar (Area 6), and Peter Oshinski (at-large).[46]

In the latter part of the 20th century, San Leandro was home to three high schools: San Leandro High School, Pacific High School (in the San Leandro Unified School District) and Marina High School (located within the San Leandro city limits but coming under the authority of the neighboring San Lorenzo Unified School District). San Leandro High School was established in 1926. As the city's population grew, so did the need for a second high school. Pacific High School was built across town nearer the industrial area adjacent to State Route 17 (now Interstate 880) and opened in 1960. It featured a round main building and more traditional outbuildings, as well as a lighted football field. (The football field at San Leandro High School did not have, and still does not have, lights.) All nighttime games for both high schools were played at the Pacific football field, named C. Burrell Field after a former San Leandro Unified School District superintendent. San Leandro High School's nighttime football games are still played there.

Student enrollment declined in San Leandro and statewide in the late 1970s through the mid 1980s. In California, public schools receive their financing from the state based on the number of students. As a result of declining enrollment and corresponding decreases in state funds, both the San Leandro and San Lorenzo school districts were forced to close schools in the 1980s.

The San Leandro school district could not afford to operate two comprehensive high schools given the decline in enrollment. Amid much controversy, the school board voted to close Pacific High School, which graduated its last class in 1983. Those who wished to keep Pacific High School open cited the fact that it was a much newer facility and handicap accessible, with a more modern football field. Those who were in favor of retaining San Leandro High School maintained that it was a larger campus and therefore had more room to house both school populations; but planned on using Marina High School as a buffer. Through failed dealings and negotiations with the San Lorenzo Unified School District, Marina closed its doors shortly after leaving the City of San Leandro with only 1 high school instead of 3.[citation needed]

In 1989, the San Leandro school district sold the property on which Pacific High School was located and the site was developed into the Marina Square Shopping Center. The school's adjacent football field, Burrell Field, and baseball fields were retained. In 2012, the voters of San Leandro approved the Measure M $50 million construction bond for the renovation of Burrell Field and the baseball fields.

In the 1990s and continuing into the 21st century, student enrollment in the San Leandro school district increased. A new science wing was built at San Leandro High School followed by an Arts Education Center with a performing arts theater. In 2010, a separate campus one block from the main campus at San Leandro High School was opened for 9th grade students and is named after the civil rights leader Fred T. Korematsu, who had many connections to San Leandro and lived close to the city.

In 2018, the California State Department of Education selected James Madison Elementary as one of 21 elementary schools across Alameda County, and the only school in San Leandro, as a 2018 California Distinguished School.[47]

San Leandro High School is home to such academic programs as the Business Academy, Social Justice Academy, and San Leandro Academy of Multimedia (SLAM). One of the award-winning national programs located in San Leandro is Distributed Education Clubs of America (DECA), an association for marketing students. In 2007, six students from San Leandro High School won in their competitive events and won a slot to compete in Orlando, Florida, on April 27, 2007.

In 2018, the College Board Advanced Placement named the San Leandro Unified School District a District of the Year for being the national leader among medium-sized school districts in expanding access to Advanced Placement Program (AP) courses while simultaneously improving AP Exam performance. The San Leandro Unified School District was one of 447 school districts across the U.S. and Canada that achieved placement on the annual AP District Honor Roll.

From this list, three AP Districts of the Year were selected based on an analysis of three academic years of AP data. SLUSD was chosen for the 'medium' district population size, which is defined as having between 8,000 and 49,999 students. SLUSD was the only district in the state, and was one of only three districts in the nation, to be honored with this recognition.[48]

A number of students residing in San Leandro attend San Lorenzo Unified School District schools, including Arroyo High School, Washington Manor Middle School and Corvallis Elementary School, due to proximity to the San Leandro/San Lorenzo border.

The rest of San Leandro is served by San Leandro Unified School District.

Government

editSan Leandro is a charter city with a Mayor-Council-Manager form of government.[49] The City Manager is Fran Robustelli. San Leandro city hall was built in 1939.

Mayor Juan González III was elected in November 2022, and serves on the City Council with six Council members. Council members are elected by all voters in the city using instant-runoff voting. However, the Council members must reside within the district they represent. The San Leandro City Council members are Sbeydeh Viveros-Walton (District 1), Bryan Azevedo (District 2), Victor Aguilar, Jr. (District 3), Fred Simon (District 4), Xouhao Bowen (District 5), and Pete Ballew (District 6).[9]

Politics

editIn 2017, San Leandro had 45,257 registered voters with 26,421 (58.4%) registered as Democrats, 5,271 (11.6%) registered as Republicans, and 11,723 (25.9%) were decline to state voters.[50]

Transportation

editSan Leandro is served by the Interstate 880, 580 and 238 freeways connecting to other parts of the Bay Area. East 14th Street (SR-185) is a major thoroughfare in downtown and continues towards East Oakland and Hayward. Davis Street is also another major street that intersects East 14th Street in downtown before heading towards the San Francisco Bay. Public transportation is provided by the Bay Area Rapid Transit BART District with the San Leandro and Bayfair stations serving the city. San Leandro LINKS provides free bus shuttle service for the western part of the city to the San Leandro BART station and AC Transit is the local bus provider for the city. A senior-oriented local bus service, Flex Shuttle, also operates within the city, as does East Bay Paratransit, which provides shuttle type transportation to residents with disabilities.

Healthcare

editThe Alameda County Medical Center's psychiatric hospital, the John George Psychiatric Pavilion, is located nearby in San Leandro.[51] Fairmont Hospital, also located close by, is an Acute Rehabilitation, Neuro-Respiratoy and HIV care center.[52] San Leandro Hospital is the city's full service hospital.[53] Also present within the city are Kindred Hospital – San Francisco Bay Area, a long-term acute care facility, and the sub-acute unit of the nursing home care facility, Providence Group, Inc's All Saint's Subacute. A Kaiser Permanente Medical Center opened in June 2014, providing Emergency Medical Services.[54]

Parks

editThe San Leandro Marina, which contains group picnic areas and trails, as well as docking facilities, is part of the San Leandro Shoreline Recreation Area.[55] In addition to Marina Park, the City of San Leandro maintains and services 16 other parks throughout the city, all of which are available for use by residents and visitors alike. The Department of Recreation and Human Services for the City of San Leandro also staffs and maintains the Marina Community Center, the San Leandro Senior Community Center and the San Leandro Family Aquatic Center. Adjacent Lake Chabot Regional Park is popular for its scenic hiking trails, camping, and fishing. Although located in Castro Valley,[51] the Fairmont Ridge Staging Area is the location of the Children's Memorial Grove, which consists of an Oak grove and a stone circle, with annual plaques listing the names of all children who have died as a result of violence in Alameda County.[56]

Notable people

editThis article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2009) |

- Stuart Alexander, sausage maker and mass murderer[57]

- Joe Alves, film production designer, worked on three of Jaws films, born in San Leandro

- Richard Aoki, activist, charter member of Black Panther Party, born in San Leandro in 1938[58]

- C.L. Best, co-founder of Caterpillar, Inc.

- Daniel Best, manufacturer and pioneer in the development of farming equipment

- Lloyd Bridges, actor, film and television star, born in San Leandro on January 15, 1913[59]

- Brian Copeland, comedian, writer, moved to San Leandro in 1972; author of "Not a Genuine Black Man," about growing up black in then all-white San Leandro

- Ellen Corbett, state senator (later moved to Hayward, California)

- Dennis Dixon, quarterback for University of Oregon and NFL's Philadelphia Eagles; attended San Leandro High School[60]

- Carl Friden, Swedish American who started business Friden, Inc. in San Leandro in 1934

- Kathy Garver, actress, best known for TV series Family Affair, was raised in San Leandro, where she attended school

- Curtis Goodwin, Major League Baseball player from 1995 to 1999; graduated from San Leandro High School

- Chuck Hayes, NBA basketball player for Houston Rockets, born in San Leandro on June 11, 1983; former college basketball star for Kentucky Wildcats

- Leonard Haze, professional drummer and co-founding member of rock and roll band Y&T, was a longtime San Leandro resident and San Leandro High School graduate

- Pat Hurst, professional golfer and NCAA women's champion, born in San Leandro on May 23, 1969

- Derrick Jasper, college basketball player for UNLV Runnin' Rebels and Kentucky Wildcats; born in San Leandro on April 13, 1988

- Fred Korematsu, see Korematsu v. United States, resident of, and arrested in, San Leandro

- Art Larsen, professional tennis player, graduated from San Leandro High School, top-ranked in U.S. in 1950; lived in San Leandro until his death on December 7, 2012

- Tony Lema, professional golfer, moved to San Leandro in 1940 at age six; in June 1983, Tony Lema Golf Course was dedicated in San Leandro

- Bill Lockyer, former State Treasurer and Attorney General of California; served as President pro Tempore of the California State Senate; graduated from San Leandro High School and served on the San Leandro School Board from 1968 to 1973

- Todd Marinovich, former quarterback for USC and NFL's Oakland Raiders, born in San Leandro in 1969[61]

- Dave McCloughan, NFL defensive back; born in San Leandro on November 20, 1966

- Andrew McGuire, consumer advocate, led 30-year campaign to mandate fire-safe cigarettes worldwide, MacArthur Fellow, attended Pacific High class of 1963, John Muir Junior High, Monroe and Cleveland Elementary Schools

- Russell Means, an Oglala Sioux activist for rights of Native American people, whose family moved to San Leandro in 1942; he graduated from San Leandro High School in 1958

- Russ Meyer, film director, born in San Leandro on March 21, 1922

- Natali Morris, technology news journalist and online media personality, born in San Leandro

- Arlen Ness, custom motorcycle designer

- Greg Norton, Major League Baseball player, hitting coach for Auburn University; born in San Leandro on July 6, 1972

- Jarrad Page, starting safety for Kansas City Chiefs; lettered three years at San Leandro High School

- Harold Peary, actor, comedian and singer in radio, film, television and animation; born in San Leandro

- Tony Robello, Major League Baseball second baseman for Cincinnati Reds; born in San Leandro in 1914

- Katherine Sarafian, PIXAR producer

- David Silveria, musician (drummer for Korn), born in San Leandro on September 21, 1972

- Jim Sorensen, track and field athlete, primarily middle-distance races; Masters M40 world record holder at 800 meters and former Masters M40 world record holder at 1500

- Dorothy Warenskjold, lyric soprano, born in San Leandro in 1921

- Harry Yoon, film editor, lived in San Leandro and graduated from San Leandro High School in 1989

In popular culture

edit- In The Princess Diaries, the cable car conductor, Bruce Macintosh, proclaims that he is from San Leandro.

- In Heart and Souls, Robert Downey Jr. finds out that one of the people he is searching for died in San Leandro.

- In the alternative punk/ska band Camper Van Beethoven's song "Tania", San Leandro is (incorrectly) named as the city in which Patty Hearst's photo was taken during a bank robbery.

- The music video for the song "High and Dry" by alternative rock band Radiohead is set in the former Dick's Restaurant and Satellite Sports Lounge.[62]

Sister cities

editSan Leandro is twinned with the following cities:[63]

- Naga, Philippines, since 1989

- Calabanga, Camarines Sur, Philippines, Since 2007[64]

- Ponta Delgada, Azores, Portugal, since 1970

- Ribeirão Preto, Brazil, since 1962

Friendship city

- Yangchun, China, since 2007

See also

edit- Casa de Estudillo, the final home of José Joaquín Estudillo, since 1938 a California Historical Landmark

References

edit- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ a b Simons 2008, p. 8.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report". City of San Leandro. 2019. p. vi. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020.

- ^ "City Manager". City of San Leandro. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved February 26, 2019.

- ^ "City Manager Appointed" (Press release). City of San Leandro. May 4, 2021.

- ^ "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "Senators". State of California. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- ^ "California's 12th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Mayor & City Council". City of San Leandro. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2020.

- ^ "San Leandro". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: San Leandro city, California". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

- ^ "PRESS RELEASE CMO2020-03-16-20". City of San Leandro. March 16, 2020.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ Kyle, Douglas E.; Hoover, Mildred Brooke (2002). Historic Spots in California. Stanford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8047-4483-6.

- ^ "San Leandro, Cal. - David Rumsey Historical Map Collection".

- ^ Rogers, Meg (2008). The Portuguese in San Leandro. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5833-2.

- ^ a b Suburban Wall, documentary, 1971; Invisible Wall, documentary, 1981; "Not a Genuine Black Man: Or How I Claimed My Piece of Ground in the Lily-White Suburbs" Brian Copeland, 2006

- ^ Simons, Cynthia Vrilakas (2008). San Leandro. Images of America. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5937-7.

- ^ "San Leandro Bytes: New Census Data Puts San Leandro's 2010 Population at 84,950". Archived from the original on May 6, 2011.

- ^ CH2M Hill, California Department of Health Services, Toxic Substances Control Division, Phase I Remedial Investigation Rpt, 1465 Factor Avenue, San Leandro, California (1987).

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Andy Kratter, Mark Weisman and Jill Buxton, Environmental Initial Study, Aladdin Avenue/Fairway Drive Overcrossing of I-880, Earth Metrics, Caltrans and city of San Leandro Rpt 9551, 1990

- ^ HAYWARD FAULT CROSSING FOOTHILL BOULEVARD, SAN LEANDRO

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – San Leandro city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – San Leandro city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – San Leandro city, California". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – San Leandro city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Moriki, Darin (August 11, 2017). "Business park to replace old Kraft Foods plant in San Leandro". Bay Area News Group.

- ^ "Greenhouse Marketplace Shopping Center (in Alameda County, CA)".

- ^ "Marina Square". Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ "Pelton Plaza". San Leandro Patch. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2011.

- ^ "Guest commentary: San Leandro has come a very long way in last three years". East Bay Times. January 14, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "San Leandro entices tech startups, entrepreneurs". East Bay Times. August 5, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "Lit San Leandro". City of San Leandro. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "San Leandro builds 'fiber optic loop' in bid to become a high-tech hub". East Bay Times. January 16, 2012. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Abate, Tom (September 28, 2012). "Federal Grant To Extend San Leandro Fiber Loop". San Leandro, CA Patch. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "About Us". Lit San Leandro. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ "Project Overview". Lit San Leandro. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "The Zero Net Energy Center". StopWaste. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ "Archived". SFGate. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ "Assemblywoman Mary Hayashi to Present Resolution to Red Top Electric" (press release). October 15, 2012. Archived from the original on October 3, 2020.

- ^ "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report". City of San Leandro. 2015.

- ^ "Trustee Areas". San Leandro Unified School District. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014.

- ^ "Board of Trustees". San Leandro Unified School District. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ "San Leandro Unified School District, James Madison Elementary Named a 2018 California Distinguished School". May 16, 2018. [dead link]

- ^ San Leandro Unified School District, San Leandro Unified School District Awarded National "Advanced Placement District of the Year" by the College Board [dead link]

- ^ San Leandro City Charter, Section 125

- ^ "Report of Registration as of February 10, 2017 – Registration by Political Subdivision by County" (PDF). Elections and Voter Information. California Secretary of State. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2017.

- ^ a b "Alameda County Unicorporated Community Locator". communitylocator.acgov.org. Retrieved February 16, 2021.

- ^ Fairmont Hospital website Archived May 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ San Leandro Hospital website

- ^ Rauber, Chris (May 30, 2014). "Kaiser set to open high-tech $600 million San Leandro hospital on Tuesday". San Francisco Business Times. American City Business Journals.

- ^ "City of San Leandro – Marina". Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- ^ "Children's Memorial Project". Alameda County. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- ^ Henry K. Lee (December 28, 2005). "Sausage king dies in his cell on Death Row / Cause of death not known for man who murdered 3". SFGate. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Puck Lo (November 12, 2009). "Film on former Panther Richard Aoki debuts". Oakland North. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ Tom Weaver (n.d.). "Lloyd Bridges Biography". IMDb. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Mitch Stephens (November 29, 2002). "San Leandro quarterback wants dream finish / Dennis Dixon's goal is to beat De La Salle before he moves on". SFGate. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ "Todd Marinovich". Pro-Football-Reference.com. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- ^ "Dick's Restaurant gets a fresh start from son of loyal customer". The Mercury News. July 12, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "Sister Cities". City of San Leandro.

- ^ "LGU Calabanga | Home". Retrieved March 11, 2023.

External links

edit- Official website

- San Leandro Chamber of Commerce

- San Leandro Times

- San Leandro Online

- San Leandro travel guide from Wikivoyage