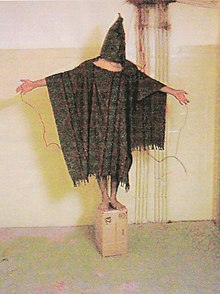

During the early stages of the Iraq War, members of the United States Army and the Central Intelligence Agency committed a series of human rights violations and war crimes against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. These abuses included physical abuse, sexual humiliation, physical and psychological torture, and rape, as well as the killing of Manadel al-Jamadi and the desecration of his body.[3][4][5][6] The abuses came to public attention with the publication of photographs by CBS News in April 2004, causing shock and outrage and receiving widespread condemnation within the United States and internationally.[7]

The George W. Bush administration stated that the abuses at Abu Ghraib were isolated incidents and not indicative of U.S. policy.[8][9]: 328 This was disputed by humanitarian organizations including the Red Cross, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch, which stated that the abuses were part of a wider pattern of torture and brutal treatment at American overseas detention centers, including those in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and at Guantanamo Bay (GTMO).[9]: 328 There were also 36 prisoners killed at Abu Ghraib due to insurgent mortar attacks, which provoked further criticism due to the facility's location in a combat zone.[10] The International Committee of the Red Cross reported that most detainees at Abu Ghraib were civilians with no links to armed groups.[11]

Documents known as the Torture Memos came to light a few years later. These documents, prepared in the months leading up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States Department of Justice, authorized certain "enhanced interrogation techniques" (generally considered to involve torture) of foreign detainees. The memoranda also argued that international humanitarian laws, such as the Geneva Conventions, did not apply to American interrogators overseas. Several subsequent U.S. Supreme Court decisions, including Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006), overturned Bush administration policy, ruling that the Geneva Conventions do apply.

In response to the events at Abu Ghraib, the United States Department of Defense removed 17 soldiers and officers from duty. Eleven soldiers were charged with dereliction of duty, maltreatment, aggravated assault and battery. Between May 2004 and April 2006, these soldiers were court-martialed, convicted, sentenced to military prison, and dishonorably discharged from service. Two soldiers, found to have perpetrated many of the worst offenses at the prison, Specialist Charles Graner and PFC Lynndie England, were subject to more severe charges and received harsher sentences. Graner was convicted of assault, battery, conspiracy, maltreatment of detainees, committing indecent acts and dereliction of duty; he was sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and loss of rank, pay, and benefits.[12] England was convicted of conspiracy, maltreating detainees, and committing an indecent act and sentenced to three years in prison.[13] Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, the commanding officer of all detention facilities in Iraq, was reprimanded and demoted to the rank of colonel. Several more military personnel accused of perpetrating or authorizing the measures, including many of higher rank, were not prosecuted. In 2004, President George W. Bush and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld apologized for the Abu Ghraib abuses.

Background

editWar on terror

editThe war on terror, also known as the Global War on Terrorism, is an international military campaign launched by the United States government after the September 11 attacks.[14] U.S. President George W. Bush first used the phrase "war on terrorism" on September 16, 2001,[15][16] and then used the phrase "war on terror" a few days later in a speech to Congress.[17][18] In the latter speech, Bush stated, "Our enemy is a radical network of terrorists and every government that supports them."[18][19]

Iraq War

editThe Iraq War began in March 2003 as an invasion of Ba'athist Iraq by a force led by the United States.[20][21] The Ba'athist government led by Saddam Hussein was toppled within a month. This conflict was followed by a longer phase of fighting in which an insurgency emerged to oppose the occupying forces and the post-invasion Iraqi government.[22] During this insurgency, the United States was in the role of an occupying power.[22]

Abu Ghraib prison

editThe Abu Ghraib prison in the town of Abu Ghraib was one of the most notorious prisons in Iraq during the government of Saddam Hussein. The prison was used to hold approximately 50,000 men and women in poor conditions, and torture and execution were frequent.[23][better source needed] The prison was located on about 110 hectares (272 acres) of land 32 kilometers (20 miles) west of Baghdad.[24] After the collapse of Saddam Hussein's government, the prison was looted and everything that was removable was carried away. Following the invasion, the U.S. army refurbished it and turned it into a military prison.[23] It was the largest of several detention centers in Iraq used by the U.S. military.[25] In March 2004, during the time that the U.S. military was using the Abu Ghraib prison as a detention facility, it housed approximately 7,490 prisoners.[26] At its peak, it held an estimated 8,000 detainees.[27]

Three categories of prisoners were imprisoned at Abu Ghraib by the U.S. military. These were "common criminals", as well as individuals suspected of being leaders of the insurgency and individuals suspected of committing crimes against the occupational force led by the U.S.[28] Although most prisoners lived in tents in the yard, the abuses took place inside cell blocks 1a and 1b.[24] The 800th Military Police Brigade, from Uniondale, New York, was responsible for running the prison.[25] The brigade was commanded by Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, who was in charge of all of the U.S.-run prisons in Iraq. She did not have previous experience in running a prison.[28] The individuals who committed abuses at the prison were members of the 372nd Military Police Company, which was a constituent of the 320th Military Police Battalion, which was overseen by Karpinski's Brigade headquarters.[29]

The Fay Report noted that "contracting-related issues contributed to the problems at Abu Ghraib prison". Over half the interrogators working at the prison were employees of CACI International, while Titan Corporation supplied linguistics personnel. In his report, General Fay notes that "The general policy of not contracting for intelligence functions and services was designed in part to avoid many of the problems that eventually developed at Abu Ghraib".[30]

First reports of human rights abuses

editIn June 2003, Amnesty International published reports of human rights abuses by the U.S. military and its coalition partners at detention centers and prisons in Iraq.[31] These included reports of brutal treatment at Abu Ghraib prison, which had once been used by the government of Saddam Hussein, and had been taken over by the United States after the invasion. On June 20, 2003, Abdel Salam Sidahmed, deputy director of AI's Middle East Program, described an uprising by the prisoners against the conditions of their detention, saying "The notorious Abu Ghraib Prison, centre of torture and mass executions under Saddam Hussein, is yet again a prison cut off from the outside world. On June 13, there was a protest in this prison against indefinite detention without trial. Troops from the occupying powers killed one person and wounded seven."[31]

On July 23, 2003, Amnesty International issued a press release condemning widespread human rights abuses by U.S. and coalition forces. The release stated that prisoners had been exposed to extreme heat, not provided clothing, and forced to use open trenches for toilets. They had also been tortured, with the methods including denial of sleep for extended periods, exposure to bright lights and loud music, and being restrained in uncomfortable positions.[32]

On November 1, 2003, the Associated Press presented a special report on the massive human rights abuses at Abu Ghraib. Their report began; "In Iraq's American detention camps, forbidden talk can earn a prisoner hours bound and stretched out in the sun, and detainees swinging tent poles rise up regularly against their jailers, according to recently released Iraqis." The report went on to describe abuse of the prisoners at the hands of their American captors: "'They confined us like sheep,' the newly freed Saad Naif, 38, said of the Americans. 'They hit people. They humiliated people.'" In response, U.S. Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, who oversaw all U.S. detention facilities in Iraq, claimed that prisoners were being treated "humanely and fairly".[33] The AP report also stated that as of November 1, 2003, there were two legal cases pending against U.S. military personnel; one involving the beating of an Iraqi prisoner, while the other arose out of the death of a prisoner in custody.[33]

Since the beginning of the invasion, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) had been allowed to oversee the prison, and submitted reports about the treatment of the prisoners. In response to an ICRC report, Karpinski stated that several of the prisoners were intelligence assets, and therefore not entitled to complete protection under the Geneva Conventions.[25] The ICRC reports led to Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, the commander of the Iraqi task force, appointing Major General Antonio Taguba to investigate the allegations on January 1, 2004.[25] Taguba submitted his findings (the Taguba Report) in February 2004, stating that "numerous incidents of sadistic, blatant, and wanton criminal abuses were inflicted on several detainees. This systemic and illegal abuse of detainees was intentionally perpetrated by several members of the military police guard force."[25] The report stated that there was widespread evidence of this abuse, including photographic evidence. The report was not released publicly.[23][34]

The scandal came to widespread public attention in April 2004, when a 60 Minutes II news report was aired on April 28 by CBS News, describing the abuse, including pictures showing military personnel taunting naked prisoners.[9][24][25][35] An article was published by Seymour M. Hersh in The New Yorker magazine, posted online on April 30 and published days later in the May 10 issue,[23] which also had a widespread impact.[35] The photographs were subsequently reproduced in the press across the world.[25] The details of the Taguba report were made public in May 2004. Shortly afterwards, U.S. President George W. Bush stated that the individuals responsible would be "brought to justice", while United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan said that the effort to reconstruct a government in Iraq had been badly damaged.[25]

Authorization of torture

editExecutive order

editOn December 21, 2004, the American Civil Liberties Union released copies of internal memoranda from the Federal Bureau of Investigation that it had obtained under the Freedom of Information Act. These discussed torture and abuse at prisons in Guantanamo Bay detention camp, Afghanistan, and Iraq. One memorandum dated May 22, 2004 was from an individual described as the "On Scene Commander – Baghdad", but whose name had been redacted.[36] This individual referred explicitly to an executive order that sanctioned the use of extraordinary interrogation tactics by U.S. military personnel. The torture methods sanctioned included sleep deprivation, hooding prisoners, playing loud music, removing all detainees' clothing, forcing them to stand in so-called "stress positions", and the use of dogs. The author also stated that the Pentagon had limited use of the techniques by requiring specific authorization from the chain of command. The author identifies "physical beatings, sexual humiliation or touching" as being outside the Executive Order. This was the first internal evidence since the Abu Ghraib prisoner abuse affair became public in April 2004 that forms of coercion of captives had been mandated by the president of the United States.[37]

Authorization from Ricardo Sanchez

editDocuments obtained by The Washington Post and the ACLU showed that Ricardo Sanchez, who was a Lieutenant General and the senior U.S. military officer in Iraq, authorized the use of military dogs, temperature extremes, reversed sleep patterns, and sensory deprivation as interrogation methods in Abu Ghraib.[38] A November 2004 report by Brigadier General Richard Formica found that many troops at the Abu Ghraib prison had been following orders based on a memorandum from Sanchez, and that the abuse had not been carried out by isolated "criminal" elements.[39] ACLU lawyer Amrit Singh said in a statement from the union that "General Sanchez authorized interrogation techniques that were in clear violation of the Geneva Conventions and the army's own standards."[40] In an interview for her hometown newspaper The Signal, Karpinski stated that she had seen unreleased documents from Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld which authorized the use of these tactics on Iraqi prisoners.[41]

Authorization from Donald Rumsfeld

editA 2004 report by the New Yorker stated that Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld had authorized the interrogation tactics used in Abu Ghraib, and which had previously been used by the U.S. in Afghanistan.[42] In November 2006, Janis Karpinski, who had been in charge of Abu Ghraib prison until early 2004, told Spain's El País newspaper that she had seen a letter signed by Rumsfeld, which allowed civilian contractors to use techniques such as sleep deprivation during interrogation. "The methods consisted of making prisoners stand for long periods, sleep deprivation... playing music at full volume, having to sit in uncomfortably ... Rumsfeld authorized these specific techniques."[43] According to Karpinski, the handwritten signature was above his printed name, and the comment "Make sure this is accomplished" was in the margin in the same hand-writing.[43] Neither the Pentagon nor U.S. Army spokespeople in Iraq commented on the accusation. In 2006, a criminal complaint was filed in a German Court against Donald Rumsfeld by eight former soldiers and intelligence operatives, including Karpinski and former army counterintelligence special agent David DeBatto. Among other things, the complaint stated that Rumsfeld both knew of and authorized so-called "enhanced interrogation techniques" that he knew to be illegal under international law.[43][44][45][46][47]

Prisoner abuse

editDeath of Manadel al-Jamadi

editManadel al-Jamadi, a prisoner at Abu Ghraib prison, died after CIA officer Mark Swanner[48] and a private contractor ("identified in military-court papers only as 'Clint C.'"[48]) interrogated and tortured him in November 2003. After al-Jamadi's death, his corpse was packed in ice; the corpse was in the background for widely reprinted photographs of grinning U.S. Army specialists Sabrina Harman and Charles Graner, each of whom offered a "thumbs-up" gesture. Al-Jamadi had been a suspect in a bomb attack that killed 12 people in a Baghdad Red Cross facility, even though there was no confirmation of his involvement in these attacks.[49] A military autopsy declared al-Jamadi's death a homicide. No one has been charged with his death. In 2011, Attorney General Eric Holder said that he had opened a full criminal investigation into al-Jamadi's death.[50] In August 2012, Holder announced that no criminal charges would be brought.[51]

Prisoner rape

editStripping prisoners of their clothes was a common form of sexual humiliation and degradation during the torture at Abu Ghraib.[52] In 2004, Antonio Taguba, a major general in the U.S. Army, wrote in the Taguba Report that a detainee had been sodomized with "a chemical light and perhaps a broomstick."[53] In 2009, Taguba stated that there was photographic evidence of American soldiers and translators having raped detainees at Abu Ghraib.[54] An Abu Ghraib detainee told investigators that he heard an Iraqi teenage boy screaming, and saw an Army translator raping him, while a female soldier took pictures.[55] A witness identified the alleged rapist as an American-Egyptian who worked as a translator. In 2009, he was the subject of a civil court case in the United States.[54] Another photo shows an American soldier apparently raping a female prisoner.[54] Other photos show interrogators sexually assaulting prisoners with objects including a truncheon, wire and a phosphorescent tube, and a female prisoner having her clothing forcibly removed to expose her breasts.[54] Taguba supported United States President Barack Obama's decision not to release the photos, stating, "These pictures show torture, abuse, rape and every indecency."[54] Obama, who had initially agreed to release the photographs, changed his mind after lobbying from senior military figures; Obama stated that their release could put troops in danger and "inflame anti-American public opinion".[54]

In other instances of sexual abuse, soldiers were found to have raped female inmates. Senior U.S. officials admitted that rape had taken place at Abu Ghraib.[56][57] Some of the women who had been raped became pregnant, and in some cases, were later killed by their family members in what were thought to be instances of honor killing.[58] In addition, journalist Seymour Hersh alleged in July 2004 that the Department of Defense had in its possession videos showing male children being raped by Iraqi prison staff in front of female prisoners.[59]

Other abuses

editIn May 2004, The Washington Post reported evidence given by Ameen Saeed Al-Sheikh, detainee No. 151362. It quoted him as saying; "They said we will make you wish to die and it will not happen ... They stripped me naked. One of them told me he would rape me. He drew a picture of a woman to my back and made me stand in shameful position holding my buttocks apart."[55] "'Do you pray to Allah?' one asked. I said yes. They said, '[Expletive] you. And [expletive] him.' One of them said, 'You are not getting out of here healthy, you are getting out of here handicapped. And he said to me, 'Are you married?' I said, 'Yes.' They said, 'If your wife saw you like this, she will be disappointed.' One of them said, 'But if I saw her now she would not be disappointed now because I would rape her.'" "They ordered me to thank Jesus that I'm alive." "I said to him, 'I believe in Allah.' So he said, 'But I believe in torture and I will torture you.'"[55]

On January 12, 2005, The New York Times reported on further testimony from Abu Ghraib detainees. The abuses reported included urinating on detainees, pounding wounded limbs with metal batons, pouring phosphoric acid on detainees, and tying ropes to the detainees' legs or penises and dragging them across the floor.[60]

In her video diary, a prison guard said that prisoners were shot for minor misbehavior, and claimed to have had venomous snakes used to bite prisoners, sometimes resulting in their deaths. The guard said that she was "in trouble" for having thrown rocks at the detainees.[61] Hashem Muhsen, one of the naked prisoners in the human pyramid photo, later said the men were also forced to crawl around the floor naked while soldiers rode them like donkeys.[62]

Systematic torture

editOn May 7, 2004, Pierre Krähenbühl, operations director for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), stated that inspection visits made by the ICRC to detention centers run by the U.S. and its allies showed that acts of prisoner abuse were not isolated acts, but were part of a "pattern and a broad system". He went on to say that some of the incidents they had observed were "tantamount to torture".[63]

Many of the torture techniques used were developed at Guantánamo detention center, including prolonged isolation; the frequent flyer program, a sleep deprivation program whereby people were moved from cell to cell every few hours so they could not sleep for days, weeks, or even months; short shackling in painful positions; nudity; extreme use of heat and cold; the use of loud music and noise; and preying on phobias.[64]

Armed forces in the U.S. and the UK are jointly trained in techniques known as resistance to interrogation (R2I) techniques. These R2I techniques are taught ostensibly to help soldiers cope with, or resist, torture if they are captured. On May 8, 2004, The Guardian reported that according to a former British special forces officer, the acts committed by the Abu Ghraib prison military personnel resembled the techniques used in R2I training.[65]

The same report stated the following:

The US commander in charge of military jails in Iraq, Major General Geoffrey Miller, has confirmed that a battery of 50-odd special "coercive techniques" can be used against enemy detainees. The general, who previously ran the prison camp at Guantanamo Bay, said his main role was to extract as much intelligence as possible.

Historian Alfred W. McCoy, who authored a book on torture in the Philippines armed forces, noted similarities in the abusive treatment of prisoners at Abu Ghraib and the techniques described in the KUBARK Counterintelligence Interrogation manual published by the United States Central Intelligence Agency in 1963. He asserts that what he calls "the CIA's no-touch torture methods" have been in continuous use by the CIA and the U.S. military intelligence since that time.[66][67]

Casualties

editA 2006 study tried to count the number of deaths by looking at public domain reports, as total figures had not been given by the U.S. government. It counted 63 detainee deaths at Abu Ghraib from all causes. Of these, 36 occurred due to insurgent mortar attacks, others were due to natural causes and homicide.[10]

The issue of deaths due to mortar attack received criticism. The Geneva Convention requires prisoners not be kept at facilities vulnerable to artillery attack.[10] As Abu Ghraib was located in the combat zone,[68] its vulnerability to such an attack had been raised early on, but ultimately it was decided to keep the prisoners there.[10][69] No other U.S. detention facility in Iraq suffered casualties due to mortar attacks.[10]

Media coverage

editAssociated Press report (2003)

editOn November 1, 2003, the Associated Press published a lengthy report on inhumane treatment, beatings, and deaths at Abu Ghraib and other American prisons in Iraq.[70] This report was based on interviews with released detainees, who told journalist Charles J. Hanley that inmates had been attacked by dogs, made to wear hoods, and humiliated in other ways.[71] The article gained little notice.[72] One freed detainee said that he wished somebody would publish pictures of what was happening.[71]

When the U.S. military first acknowledged the abuse in early 2004, much of the United States media showed little initial interest. On January 16, 2004, United States Central Command informed the media that an official investigation had begun involving abuse and humiliation of Iraqi detainees by a group of U.S. soldiers. On February 24, it was reported that 17 soldiers had been suspended. The military announced on March 21, 2004, that the first charges had been filed against six soldiers.[73][74]

60 Minutes II broadcast (2004)

editIn late April 2004, the U.S. television news-magazine 60 Minutes II, a franchise of CBS, broadcast a story on the abuse. The story included photographs depicting the abuse of prisoners.[76] The news segment was delayed by two weeks at the request of the Department of Defense and Richard Myers, an air force general and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. After learning that The New Yorker magazine planned to publish an article and photographs on the topic in its next issue, CBS proceeded to broadcast its report on April 28.[77] In the CBS report, Dan Rather interviewed then-deputy director of Coalition operations in Iraq, Brigadier General Mark Kimmitt, who said:

The first thing I'd say is we're appalled as well. These are our fellow soldiers. These are the people we work with every day, and they represent us. They wear the same uniform as us, and they let their fellow soldiers down ... Our soldiers could be taken prisoner as well. And we expect our soldiers to be treated well by the adversary, by the enemy. And if we can't hold ourselves up as an example of how to treat people with dignity and respect ... We can't ask that other nations do that to our soldiers as well. ... So what would I tell the people of Iraq? This is wrong. This is reprehensible. But this is not representative of the 150,000 soldiers that are over here ... I'd say the same thing to the American people ... Don't judge your army based on the actions of a few.[76]

Kimmitt also acknowledged that he knew of other cases of abuse during the American occupation of Iraq.[76] Bill Cowan, a former Marine lieutenant colonel, was also interviewed, and said: "We went into Iraq to stop things like this from happening, and indeed, here they are happening under our tutelage."[76] In addition, Rather interviewed Army Reserve Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick, who was party to some of the abuses. Frederick's civilian job was as a corrections officer at a Virginia prison. He said, "We had no support, no training whatsoever. And I kept asking my chain of command for certain things ... like rules and regulations, and it just wasn't happening."[76] Frederick's video diary, sent home from Iraq, provided some of the images used in the story. In it he listed detailed, dated entries that chronicled abuse of CIA prisoners, as well as their names: "The next day the medics came in and put his body on a stretcher, placed a fake [intravenous drip] in his arm and took him away. This [CIA prisoner] was never processed and therefore never had a number."[78] Frederick implicated the Military Intelligence Corps as well, saying "MI has been present and witnessed such activity. MI has encouraged and told us great job [and] that they were now getting positive results and information."[78]

New Yorker article (2004)

editIn 2004, Seymour M. Hersh authored an article in The New Yorker magazine discussing the abuses in detail, relying on a copy of the Taguba report for substantiation. Under the direction of editor David Remnick, the magazine also posted a report on its website by Hersh, along with a number of images of the torture taken by U.S. military prison guards. The article, entitled "Torture at Abu Ghraib", was followed in the next two weeks by two further articles on the same subject, "Chain of Command" and "The Gray Zone", also by Hersh.[77]

Later coverage (2006)

editIn February 2006, previously unreleased photos and videos were broadcast by SBS, an Australian television network, on its Dateline program. The Bush administration attempted to prevent release of the images in the U.S., arguing that their publication could provoke antagonism. These newly released photographs depicted prisoners crawling on the floor naked, being forced to perform sexual acts, and being covered in feces. Some images also showed prisoners killed by the soldiers, some shot in the head and some with slit throats. BBC World News stated that one of the prisoners, who was reportedly mentally unstable, was considered by prison guards as a "pet" for torture.[79] The UN expressed hope that the pictures would be investigated immediately, but the Pentagon stated that the images "have been previously investigated as part of the Abu Ghraib investigation."[80]

On March 15, 2006, Salon published what was then the most extensive documentation of the abuse.[81] A report accessed by Salon included the following summary of the material: "A review of all the computer media submitted to this office revealed a total of 1,325 images of suspected detainee abuse, 93 video files of suspected detainee abuse, 660 images of adult pornography, 546 images of suspected dead Iraqi detainees, 29 images of soldiers in simulated sexual acts, 20 images of a soldier with a Swastika drawn between his eyes, 37 images of Military Working dogs being used in abuse of detainees and 125 images of questionable acts."[81]

Coverage in Arts

editFine Arts

edit- In 2004, the International Center of Photography in New York and The Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh presented the photo exhibition "Inconvenient Evidence".[82]

- The torture scandal was provocatively dealt with by the painter Fernando Botero and was discussed controversially.[83][84][85][86][87]

- The Museo di Roma in Trastevere showed cards by Susan Crile in the exhibition "Abu Ghraib. Abuse of Power" in 2007.[88]

- Daniel Heyman showed portraits of victims of Abu Ghraib in the exhibition "I am Sorry It is Difficult to Start" at Brown University in Providence in 2007.[89]

- At the Berlin Biennale 2022, a labyrinth of horror constructed with photos by the French artist Jean-Jacques Lebel in the Rieckhallen of the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum caused a stir and a letter of protest from artists.[90][91][92][93]

Film

edit- The Turkish feature film Valley of the Wolves: Iraq depicts torture scenes from Abu Ghraib.

- The documentary Standard Operating Procedure by Errol Morris impressively illuminates the story behind the images and gives perpetrators a voice.

- A documentary directed by Rory Kennedy called Ghosts of Abu Ghraib from 2007 gives both victims and perpetrators a voice and draws a comparison to the Milgram experiment.

- Photos of the scandal are shown in Alfonso Cuarón's 2006 film Children of Men.

- War film Boys of Abu Ghraib from 2014 directed by Luke Moran.

- In the 2021 feature film The Card Counter by director Paul Schrader. The main character William Tell, played by Oscar Isaac, and Major John Gordo, played by Willem Dafoe, were previously involved in torture in Abu Ghraib.

Reactions

editUnited States

editGovernment response

editThe Bush administration did not initially readily acknowledge the abuses at Abu Ghraib. After the pictures were published and the evidence became incontrovertible, the initial reaction from the administration characterized the scandal as an isolated incident uncharacteristic of U.S. actions in Iraq.[9] Bush described the abuses as the actions of a few individuals, who were disregarding the values of the US.[9] This view was widely disputed, notably in Arab countries. In addition, the International Red Cross had been making representations about abuse of prisoners for more than a year before the scandal broke.[94] Vice President Dick Cheney's office had played a central role in eliminating limits on coercion in U.S. custody, commissioning and defending legal opinions that the administration later portrayed as the initiatives of lower-ranking officials.[95]

On May 7, 2004, President Bush publicly apologized for the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib, stating that he was "sorry for the humiliations suffered by the Iraqi prisoners and the humiliations suffered by their families". In an appearance with King Abdullah II of Jordan, Bush said he had told the king that he was "equally sorry that the people that have been seeing those pictures did not understand the true nature and the heart of America, and I assured him that Americans like me didn't appreciate what we saw and it made us sick to our stomachs". Describing the abuse as "abhorrent" and "a stain on our country's honor and our country's reputation", Bush added that "those responsible for the maltreatment 'will be brought to justice'" and that he would prevent the occurrence of future abuses.[96]

On the same day, United States Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld said the following in a hearing before the Senate Armed Services Committee:

These events occurred on my watch. As Secretary of Defense, I am accountable for them. I take full responsibility. It is my obligation to evaluate what happened, to make sure those who have committed wrongdoing are brought to justice, and to make changes as needed to see that it doesn't happen again. I feel terrible about what happened to these Iraqi detainees. They are human beings. They were in U.S. custody. Our country had an obligation to treat them right. We didn't do that. That was wrong. To those Iraqis who were mistreated by members of U.S. armed forces, I offer my deepest apology. It was un-American. And it was inconsistent with the values of our nation.[97]

He also commented on the very existence of the evidence of abuse:

We're functioning in a—with peacetime restraints, with legal requirements in a wartime situation, in the information age, where people are running around with digital cameras and taking these unbelievable photographs and then passing them off, against the law, to the media, to our surprise, when they had not even arrived in the Pentagon.[98]

Rumsfeld was careful to draw a distinction between abuse and torture: "What has been charged so far is abuse, which I believe technically is different from torture. I'm not going to address the 'torture' word."[99]

Several senators commented on Rumsfeld's testimony. Lindsey Graham stated that "the American public needs to understand we're talking about rape and murder here."[100] Norm Coleman said that "It was pretty disgusting, not what you'd expect from Americans".[101] Ben Nighthorse Campbell said "I don't know how the hell these people got into our army".[102][103]

James Inhofe, a Republican member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, stated that the events were being blown out of proportion: "I'm probably not the only one up at this table that is more outraged by the outrage than we are by the treatment ... [They] are not there for traffic violations. ... these prisoners—they're murderers, they're terrorists, they're insurgents. ... Many of them probably have American blood on their hands. And here we're so concerned about the treatment of those individuals."[104]

Other senators such as Ron Wyden said that, “I expected that these pictures would be very hard on the stomach lining, and it was significantly worse than anything that I had anticipated,”[105]

On May 26, 2004, Al Gore gave a sharply critical speech on the scandal and the Iraq War. He called for the resignations of Rumsfeld, National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice, CIA Director George Tenet, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas J. Feith, and Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence Stephen A. Cambone, for encouraging policies that led to the abuse of Iraqi prisoners and fanned hatred of Americans abroad. Gore also called the Bush administration's Iraq war plan "incompetent" and described Bush as the most dishonest president since Richard Nixon. Gore commented; "In Iraq, what happened at that prison, it is now clear, is not the result of random acts of a few bad apples. It was the natural consequence of the Bush Administration policy. The abuse of the prisoners at Abu Ghraib flowed directly from the abuse of the truth that characterized the administration's march to war and the abuse of the trust that had been placed in President Bush by the American people in the aftermath of Sept. 11th.''[106][107]

The revelations were also the impetus for the creation of the Fay Report, named for its lead author George Fay, as well as the Taguba Report.[citation needed]

Following the outcry, Major General Douglas Stone was assigned to oversee the reform of the U.S. detention system in Iraq. Conditions for detainees were reportedly improved by the time of U.S. withdrawal.[108]

Media

editSeveral periodicals, including The New York Times and The Boston Globe, called for Rumsfeld's resignation.[109]

Right-wing radio host Rush Limbaugh contended that the events were being blown out of proportion, stating that "this is no different than what happens at the Skull and Bones initiation, and we're going to ruin people's lives over it and we're going to hamper our military effort, and then we are going to really hammer them because they had a good time. You know, these people are being fired at every day. I'm talking about people having a good time, these people, you ever heard of emotional release? You [ever] heard of need to blow some steam off?"[7][110] Conservative talk show host Michael Savage said, "Instead of putting joysticks, I would have liked to have seen dynamite put in their orifices", and that "we need more of the humiliation tactics, not less." He repeatedly referred to Abu Ghraib prison as "Grab-an-Arab" prison.[111][112]

Iraqi response

editThe news website AsiaNews quoted Yahia Said, an Iraqi scholar at the London School of Economics, as saying: "The reception [of the news about Abu Ghraib] was surprisingly low-key in Iraq. Part of the reason was that rumors and tall stories, as well as true stories, about abuse, mass rape, and torture in the jails and in coalition custody have been going round for a long time. So compared to what people have been talking about here the pictures are quite benign. There's nothing unexpected. In fact what most people are asking is: why did they come up now? People in Iraq are always suspecting that there's some scheming going on, some agenda in releasing the pictures at this particular point."[113] CNN reporter Ben Wedeman reported that Iraqi reaction to George W. Bush's apology for the Abu Ghraib abuses was "mixed": "Some people react[ed] positively, saying that he's come out, he's dealing frankly and openly with the problem and that he has said that those involved in the abuse will be punished. On the other hand, there are many others who say it simply isn't enough, that they—many people noted that there was not a frank apology from the president for this incident. And, in fact, I have a Baghdad newspaper with me right now from—it's called 'Dar-es-Salaam.' That's from the Islam Iraqi Islamic Party. It says that an apology is not enough for the torture ... of Iraqi prisoners."[114]

General Stanley McChrystal, who held several command positions in the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, said that, "In my experience, we found that nearly every first-time jihadist claimed Abu Ghraib had first jolted him into action."[115] He also said that, "mistreating detainees would discredit us. ... The pictures [from] Abu Ghraib represented a setback for America's efforts in Iraq. Simultaneously undermining U.S. domestic confidence in the way in which America was operating, and creating or reinforcing negative perceptions worldwide of American values, it fueled violence".[116]

Global reaction

editThe torture? A more serious blow to the United States than September 11, 2001 attacks. Except that the blow was not inflicted by terrorists but by Americans against themselves.

The cover of the British periodical, The Economist, which had backed President Bush in the 2000 election, carried a photo of the abuse with the words "Resign, Rumsfeld".

The Bahraini English-language newspaper Daily Tribune wrote on May 5, 2004, that "The blood-boiling pictures will make more people inside and outside Iraq determined to carry out attacks against the Americans and British." The Qatari Arabic-language Al-Watan predicted on May 3, 2004 that due to the abuse, "The Iraqis now feel very angry and that will cause revenge to restore the humiliated dignity."[118]

On May 10, 2004, swastika-covered posters of Abu Ghraib abuse photographs were attached to several graves at the Commonwealth military cemetery in Gaza City. Thirty-two graves of soldiers killed in World War I were desecrated or destroyed.[119] In November 2008, Lord Bingham, the former UK Law Lord, describing the treatment of Iraqi detainees in Abu Ghraib, said: "Particularly disturbing to proponents of the rule of law is the cynical lack of concern for international legality among some top officials in the Bush administration."[120]

Scholarly analysis

editThe 2007 book The Lucifer Effect by Philip Zimbardo mentioned the abuses at Abu Ghraib to support the conclusions of the author's 1971 psychological Stanford Prison Experiment.

In 2008, scholars Alette Smeulers and Sander van Niekerk published an article entitled "Abu Ghraib and the War on Terror—a case against Donald Rumsfeld?".[9] According to the authors, the September 11 attacks led to demands from the public that U.S. president George W. Bush take actions that would prevent further attacks.[9] This pressure led to the launch of the War on Terror.[9][better source needed] Smeulers and van Niekerk argued that because the perceived enemies in the War on Terror were stateless individuals, and because the perceived threats included extreme strategies such as suicide bombing, the Bush administration was under pressure to act decisively in the War on Terror.[9] In addition, these tactics created the perception that the "legitimate" techniques used in the Cold War would not be of much use. The article noted that Vice President Dick Cheney has stated that the United States "[had] to work sort of on the dark side", and that it had to "use any means at [its] disposal".[9] Smeulers and van Niekerk opined that the abuses at Abu Ghraib constituted state-sanctioned crimes.[9] Scholar Michelle Brown agreed.[8]

A number of feminist academics have examined how ideas of masculinity and race likely influenced the violence perpetrated at Abu Ghraib.[121] Laura Sjoberg, for example, has argued that the sexual humiliation of detainees was meant to mark "the victory of hegemonic American manliness over subordinated Iraqi masculinities."[122] Similarly, Jasbir Puar’s book Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (2007) examines the feminist, queer, and American government's response to the Abu Ghraib photographs. Puar draws upon queer theory and biopolitics, among other frameworks, in her analysis and coins the term "homonationalism," short for "homonormative nationalism."[123] She discusses ideas that the soldiers’ beliefs of American cultural supremacy over the "sexually repressed" and "homophobic" Muslim detainees were used to dehumanize the victims.[124]

Repercussions

editConvictions of soldiers

editTwelve soldiers were convicted of various charges relating to the incidents, with all of the convictions including the charge of dereliction of duty. Most soldiers only received minor sentences. Three other soldiers were either cleared of charges or were not charged. No one was convicted for the murders of the detainees.

- Colonel Thomas Pappas was relieved of his command on May 13, 2005, after receiving non-judicial punishment for two instances of dereliction of duty, including that of allowing dogs to be present during interrogations. He was fined $8000 under the provisions of Article 15 of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (non-judicial punishment). He also received a General Officer Memorandum of Reprimand which effectively ended his military career. He did not face criminal prosecution.[125]

- Lieutenant Colonel Steven L. Jordan became the second highest-ranking officer to have charges brought against him in connection with the Abu Ghraib abuse on April 29, 2006.[126] Prior to his trial, eight of the twelve charges against him were dismissed, including two of the most serious, after Major General George Fay admitted that he did not read Jordan his rights before interviewing him. On August 28, 2007, Jordan was acquitted of all charges related to prisoner mistreatment and received a reprimand for disobeying an order not to discuss a 2004 investigation into the allegations.[127]

- Specialist Charles Graner was found guilty on January 14, 2005, of conspiracy to maltreat detainees, failing to protect detainees from abuse, cruelty, and maltreatment, as well as charges of assault, indecency, adultery, and obstruction of justice. On January 15, 2005, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison, dishonorable discharge, and reduction in rank to private.[12][128] Graner was paroled from the U.S. military's Fort Leavenworth prison on August 6, 2011, after serving six-and-a-half years.[129]

- Staff Sergeant Ivan Frederick pleaded guilty on October 20, 2004, to conspiracy, dereliction of duty, maltreatment of detainees, assault and committing an indecent act, in exchange for other charges being dropped. His abuses included forcing three prisoners to masturbate. He also punched one prisoner so hard in the chest that he needed resuscitation. He was sentenced to eight years in prison, forfeiture of pay, a dishonorable discharge and a reduction in rank to private.[130][131][132][133] He was released on parole in October 2007, after four years in prison.[134]

- Sergeant Javal Davis pleaded guilty on February 4, 2005, to dereliction of duty, making false official statements, and battery. He was sentenced to six months in prison, a reduction in rank to private, and a bad conduct discharge. Davis had admitted to stepping on the hands and feet of a group of handcuffed detainees and falling with his full weight on top of them.[135]

- Specialist Jeremy Sivits was sentenced on May 19, 2004, by a special court-martial to the maximum one-year sentence, in addition to a bad conduct discharge and a reduction of rank to private, upon his guilty plea.[136] He died from COVID-19 in 2022.

- Specialist Armin Cruz was sentenced on September 11, 2004, to eight months' confinement, reduction in rank to private and a bad conduct discharge in exchange for his testimony against other soldiers.[137]

- Specialist Sabrina Harman was sentenced on May 17, 2005, to six months in prison and a bad conduct discharge after being convicted on six of the seven counts. Previously, she had faced a maximum sentence of five years.[138] Harman served her sentence at Naval Consolidated Brig, Miramar.[139]

- Specialist Megan Ambuhl was convicted on October 30, 2004, of dereliction of duty. She was dishonorably discharged, reduced in rank to private, and ordered to forfeit half a month of pay.[140]

- Private First Class Lynndie England was convicted on September 26, 2005, of one count of conspiracy, four counts of maltreating detainees and one count of committing an indecent act. She was acquitted on a second conspiracy count. England had faced a maximum sentence of ten years. She was sentenced on September 27, 2005, to three years' confinement, forfeiture of all pay and allowances, reduction to Private (E-1) and received a dishonorable discharge.[132] England served her sentence at Naval Consolidated Brig, Miramar.[141] She was paroled on March 1, 2007, after having served one year and five months.[141]

- Sergeant Santos Cardona was convicted of dereliction of duty and aggravated assault, the equivalent of a felony in the U.S. civilian justice system. Cardona was sentenced to 90 days of hard labor, which he served at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.[142] He was also fined and demoted. Cardona was unable to re-enlist due to his conviction. However, on September 29, 2007, Cardona left the Army with an honorable discharge.[143] In 2009, he was killed in action while working as a government contractor in Afghanistan.[143]

- Specialist Roman Krol pleaded guilty on February 1, 2005, to conspiracy and maltreatment of detainees at Abu Ghraib. He was sentenced to ten months' confinement, reduction in rank to Private, and a bad conduct discharge.[144]

- Specialist Israel Rivera, who was present during abuse on October 25, was under investigation but was never charged and testified against other soldiers.[145][137]

- Sergeant Michael Smith was found guilty on March 21, 2006, of two counts of prisoner maltreatment, one count of simple assault, one count of conspiracy to maltreat, one count of dereliction of duty and a final charge of an indecent act, and sentenced to 179 days in prison, a fine of $2,250, a demotion to private, and a bad conduct discharge.[146]

Senior personnel

edit- Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, who had been commanding officer at the prison, was demoted to colonel on May 5, 2005. In a BBC interview, Janis Karpinski said that she was being made a scapegoat, and that the top U.S. commander for Iraq, General Ricardo Sanchez, should be asked what he knew about the abuse.[147] Karpinski told a reporter in 2014 that, at the time, military intelligence personnel had informed her that 75 percent of the inmates were innocent of the crimes they had been accused of and had been detained simply by being in the wrong place at the wrong time. She later learned that this figure was closer to 90 percent.[148]

- Donald Rumsfeld stated in February 2005 that as a result of the Abu Ghraib scandal, he had twice offered to resign from his post of Secretary of Defense, but U.S. President George W. Bush declined both offers.[149]

- Jay Bybee, the author of the Justice Department memo defining torture as activity producing pain equivalent to the pain experienced during death and organ failure,[150] was nominated by President Bush to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he began service in 2003.[151]

- Michael Chertoff, who as head of the Justice Department's criminal division advised the CIA on the outer limits of legality in coercive interrogation sessions, was selected by President Bush to fill the cabinet-level vacancy at Secretary of Homeland Security created by the departure of Tom Ridge.[152][153]

- Karpinski's immediate operational supervisor and Sanchez's deputy, Major General Walter Wojdakowski, was cleared of all charges, and was subsequently appointed Chief of the U.S. Army Infantry School at Fort Benning.[154]

- Pappas's boss, Barbara Fast, was subsequently appointed Chief of the U.S. Army Intelligence Center at Fort Huachuca.[155]

The Final Report of the Independent Panel to Review Department of Defense detention operations specifically absolved U.S. military and political leadership from culpability: "The Panel finds no evidence that organizations above the 800th MP brigade or the 205th MI Brigade-level were directly involved in the incidents at Abu Ghraib."[156]

Legal issues

editInternational law

editSince much of the abuse took place while Iraq was occupied by the United States under the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), Common Article Two of the Geneva Conventions (which governs rules applicable to international armed conflict) applied to the situation. Common Article Two states:

In addition to the provisions which shall be implemented in peacetime, the present Convention shall apply to all cases of declared war or of any other armed conflict which may arise between two or more of the High Contracting Parties, even if the state of war is not recognized by one of them.

The Convention shall also apply to all cases of partial or total occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party, even if the said occupation meets with no armed resistance.[157][158][159][160]

The United States has ratified the 1907 Hague Convention IV - Laws and Customs of War on Land and the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions,[161] as well as the United Nations Convention against Torture.[162] The Bush Administration took the position that: "Both the United States and Iraq are parties to the Geneva Conventions. The United States recognizes that these treaties are binding in the war for the 'liberation of Iraq'".[163]

The Convention Against Torture defines torture in the following terms:

For the purposes of this Convention, the term "torture" means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person, information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

— United Nations Convention Against Torture, (Article 1)

According to Human Rights Watch:

Al-Qaeda detainees would likely not be accorded Prisoner of War (POW) status, but the Conventions still provide explicit protections to all persons held in an international armed conflict, even if they are not entitled to POW status. Such protections include the right to be free from coercive interrogation, to receive a fair trial if charged with a criminal offense, and, in the case of detained civilians, to be able to appeal periodically the security rationale for continued detention.[164]

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) concluded in its confidential February 2004 report to the Coalition Forces (CF) that it had documented "serious violations" of international law in connection with prisoners held in Iraq. The ICRD added that its report "establishes that persons deprived of their liberty face the risk of being subjected to a process of physical and psychological coercion, in some cases tantamount to torture, in the early stages of the internment process".[94] There were several major violations described in the ICRC report. These included brutality against protected persons upon capture and initial custody, sometimes causing death or serious injury; absence of notification of arrest of persons deprived of their liberty to their families causing distress among persons deprived of their liberty and their families; physical or psychological coercion during interrogation to secure information; prolonged solitary confinement in cells devoid of daylight; excessive and disproportionate use of force against persons deprived of their liberty resulting in death or injury during their period of internment.[94]

Some legal experts have said that the United States could be obligated to try some of its soldiers for war crimes.[citation needed] Under the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions, prisoners of war and civilians detained in a war may not be treated in a degrading manner, and violation of that section is a "grave breach". In a November 5, 2003 report on prisons in Iraq, the Army's provost marshal, Major General Donald J. Ryder, stated that the conditions under which prisoners were held sometimes violated the Geneva Conventions.[citation needed]

United Nations resolution 1546

editIn December 2005, John Pace, human rights chief for the United Nations Assistance Mission in Iraq (UNAMI), criticized the U.S. military's practice of holding Iraqi prisoners in Iraqi facilities such as Abu Ghraib. Pace stated that this practice was not mandated by UN Resolution 1546, according to which the U.S. government has claimed a legal mandate permitting its ongoing occupation of Iraq. Pace said, "All except those held by the Ministry of Justice are, technically speaking, held against the law because the Ministry of Justice is the only authority that is empowered by law to detain, to hold anybody in prison. Essentially none of these people have any real recourse to protection and therefore we speak ... of a total breakdown in the protection of the individual in this country."[165]

Torture Memos

editAlberto Gonzales and other senior administration lawyers argued that detainees at the Guantanamo Bay detention camp and other similar prisons should be considered "unlawful combatants" and were not protected by the Geneva Conventions. These opinions were issued in multiple memoranda, known today as the "Torture Memos", in August 2002, by the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) in the U.S. Justice Department.[166] They were written by John Yoo, deputy assistant attorney-general in the OLC, and two of three were signed by his boss Jay S. Bybee. (The latter was appointed as a federal judge in 2003, starting March 21, 2003.) An additional memo was issued on March 14, 2003, after the resignation of Bybee, and just prior to the American invasion of Iraq. In it, Yoo concluded that federal laws prohibiting the use of torture did not apply to U.S. practices overseas.[167] Gonzales observed that denying coverage under the Geneva Conventions, "substantially reduces the threat of domestic criminal prosecution under the War Crimes Act."[168] Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman wrote that Gonzales's statement suggested that policy was crafted to ensure that the actions of U.S. officials could not be considered war crimes.[168][169][170][171]

Other legal proceedings

editIn Hamdan v. Rumsfeld (2006), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Common Article Three of the Geneva Conventions applied to all detainees in the War on Terror. It said that the military tribunals used to try these suspects were in violation of U.S. and international law. It said that the president could not unilaterally establish such tribunals, and that Congress needed to authorize a means by which detainees could confront their accusers and challenge their detention.[172] At the time of the court's ruling, the U.S. fought in cooperation with recognized territorial governments (including the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and the Iraqi federal government) in the War on Terror against violent non-state actors, and therefore Common Article Three was binding upon the U.S. rather than Common Article Two.

On June 27, 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the appeals of lawsuits from a group of 250 Iraqis who wanted to sue CACI International Inc. and Titan Corp. (now a subsidiary of L-3 Communications), the two private contractors at Abu Ghraib, over claims of abuse by interrogators and translators at the prison. The suits had been dismissed by the lower courts on the grounds that the companies held a derivative sovereign immunity from suits based on their status as government contractors pursuant to a battle-field preemption doctrine.[173][174]

On November 14, 2006, legal proceedings invoking universal jurisdiction were begun in Germany against Donald Rumsfeld, Alberto Gonzales, John Yoo, George Tenet and others for their alleged involvement in prisoner abuse under the command responsibility.[175][176] On April 27, 2007, the German Public Prosecutor General, Monika Harms, announced that the government would not pursue charges against Rumsfeld and the 11 other U.S. officials, stating the accusations did not apply, in part because there was insufficient evidence that the acts occurred on German soil, and because the accused did not live in Germany.[177]

In June 2011, the Justice Department announced it was opening a grand jury investigation into CIA torture which killed a prisoner.[178][179]

In June 2014, the U.S. court of appeals in Richmond, Virginia, found that an 18th-century law known as the Alien Tort Statute, allowed non-US citizens access to U.S. courts for violations of "the law of nations or a treaty of the United States". This would enable abused Iraqis to file suit against contractor CACI International. Employees of CACI International are being accused of encouraging torture and abuse as well as taking part in it as the four Iraqis contend that they were "repeatedly shot in the head with a taser gun", "beaten on the genitals with a stick", and forced to watch the "rape [of] a female detainee", during their time at the prison.[180]

As of April 2024, an Alexandria, Virginia federal civil jury was deliberating whether to hold CACI liable for its employees' torture of three Iraqi citizens at Abu Ghraib.[181][182] The case ended in a hung jury, with the majority of jurors believing that CACI should be held responsible, and a second trial began on October 30.[183] On November 12, 2024, the federal court found CACI Premier Technology liable for its involvement in the torture and ordered CACI to pay $3 million in compensatory damages to each of the three plaintiffs, plus $11 million each in punitive damages, for a total of $42 million.[184][185] Although the court found that CACI employees did not directly take part in the human rights abuses, it concluded that interrogators had instructed the military police to "soften up" prisoners for questioning by mistreating them.[186]

Military Commissions Act of 2006

editCritics consider the Military Commissions Act of 2006 an amnesty law for crimes committed in the War on Terror by retroactively rewriting the War Crimes Act.[187] It abolished habeas corpus for foreign detainees, effectively making it impossible for detainees to challenge crimes committed against them.[188][189][190][191]

Later developments

editOn October 29, 2007, the memoir of a soldier stationed in Abu Ghraib, Iraq from 2005 to 2006 was published. It was called Torture Central and chronicled many events previously unreported in the news media, including torture that continued at Abu Ghraib over a year after the abuse photos were published.[192]

In 2010, the last of the prisons were turned over to the Iraqi government to run. An Associated Press article said

Despite Abu Ghraib- or perhaps because of reforms in its wake- prisoners have more recently said they receive far better treatment in American custody than in Iraqi jails.[193]

In September 2010, Amnesty International warned in a report titled New Order, Same Abuses; Unlawful Detentions and Torture in Iraq that up to 30,000 prisoners, including many veterans of the U.S. detention system, remain detained without rights in Iraq and are frequently tortured or abused. Furthermore, it describes a detention system that has not evolved since Saddam Hussein's regime, in which human rights abuses were endemic with arbitrary arrests and secret detention common and a lack of accountability throughout the military forces. Amnesty's Middle East and North Africa director, Malcolm Smart went on to say: "Iraq's security forces have been responsible for systematically violating detainees' rights and they have been permitted. U.S. authorities, whose own record on detainees' rights has been so poor, have now handed over thousands of people detained by U.S. forces to face this catalogue of illegality, violence and abuse, abdicating any responsibility for their human rights."[194]

On October 22, 2010, nearly 400,000 secret United States Army field reports and war logs, detailing torture, summary executions and war crimes, were passed on to the British paper, The Guardian, and several other international media organisations through the whistleblowing website WikiLeaks. Among other things, the logs detail how U.S. authorities failed to investigate hundreds of reports of abuse, torture, rape, and even murder by Iraqi police and soldiers, whose conduct appeared to be systematic and normally unpunished, and that U.S. troops abused prisoners for years even after the Abu Ghraib scandal.[195][196]

In 2013, Associated Press stated that Engility Holdings, of Chantilly, Virginia, paid $5.28 million in a settlement to 71 former inmates held at Abu Ghraib and other U.S.-run detention sites between 2003 and 2007. The settlement was the first successful attempt by the detainees to obtain reparations for the abuses they had experienced.[197]

In 2014, Abu Ghraib prison was closed indefinitely by the Iraqi government over concerns that ISIL would take over the facility.[198]

In November 2024, more than two decades later, three former detainees of Abu Ghraib prison were awarded $42 million after a jury found CACI liable for conspiring with military police to inflict abuse on the prisoners.[199]

See also

editIncidents and coverage

edit- Bagram torture and prisoner abuse

- Camp Nama

- "Copper Green" (May 2004 Seymour Hersh article connecting abuse to alleged Black Ops program)

- Emad al-Janabi

- Human rights in post-invasion Iraq

- Iraq prison abuse scandals

- Maywand District murders

- Stanford prison experiment

- The Dark Side (book)

- Taxi to the Dark Side

- The Lucifer Effect

Other

edit- Criticism of the war on terror

- Disarmed Enemy Forces (redesignation of POWs after WWII to avoid having to obey international treaties on POW treatment)

- Human Rights Record of the United States

- International Criminal Court and the 2003 invasion of Iraq

- Kampala Review Conference

- Legal issues related to the September 11 attacks

- List of photographs considered the most important

- List of war crimes

- Milgram experiment

- Nuremberg principles

- Sexual assault in the United States military

- Superior orders

- Torture in the United States

- United States and the International Criminal Court

- United States war crimes

Sources

edit- ^ Higham, Scott; Stephens, Joe (May 21, 2004). "New Details of Prison Abuse Emerge". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ^ "This Happened—November 4: U.S. Army Image Of Shame". WorldCrunch. November 4, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour M. (May 17, 2004). "Chain of Command". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

NBC News later quoted U.S. military officials as saying that the unreleased photographs showed American soldiers 'severely beating an Iraqi prisoner nearly to death, having sex with a female Iraqi prisoner, and "acting inappropriately with a dead body." The officials said there also was a videotape, apparently shot by U.S. personnel, showing Iraqi guards raping young boys.'

- ^ Benjamin, Mark (May 30, 2008). "Taguba denies he's seen abuse photos suppressed by Obama: The general told a U.K. paper about images he saw investigating Abu Ghraib – not photos Obama wants kept secret". Salon.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

The paper quoted Taguba as saying, 'These pictures show torture, abuse, rape and every indecency.' ... The actual quote in the Telegraph was accurate, Taguba said – but he was referring to the hundreds of images he reviewed as an investigator of the abuse at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq

- ^ Hersh, Seymour Myron (June 25, 2007). "The General's Report: how Antonio Taguba, who investigated the Abu Ghraib scandal, became one of its casualties". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved June 17, 2007.

Taguba said that he saw "a video of a male American soldier in uniform sodomizing a female detainee"

- ^ Walsh, Joan; Michael Scherer; Mark Benjamin; Page Rockwell; Jeanne Carstensen; Mark Follman; Page Rockwell; Tracy Clark-Flory (March 14, 2006). "Other government agencies". The Abu Ghraib files. Salon.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

The Armed Forces Institute of Pathology later ruled al-Jamadi's death a homicide, caused by 'blunt force injuries to the torso complicated by compromised respiration.'

- ^ a b Sontag, Susan (May 23, 2004). "Regarding The Torture Of Others". The New York Times Magazine. Archived from the original on September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Brown, Michelle (September 2005). ""Setting the Conditions" for Abu Ghraib: The Prison Nation Abroad". American Quarterly. 57 (3): 973–997. doi:10.1353/aq.2005.0039. JSTOR 40068323. S2CID 144661236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Smeulers, Alette; van Niekirk, Sander (2009). "Abu Ghraib and the War on Terror - A case against Donald Rumsfeld?" (PDF). Crime, Law and Social Change. 51 (3–4): 327–349. doi:10.1007/s10611-008-9160-2. S2CID 145710956.

After the pictures were published the Bush administration was quick to condemn the abuse and accuse the low ranking soldiers who featured in the pictures. Secretary of Defense Rumsfeld described the abuse at Abu Ghraib as an isolated case and President Bush talked about: 'disgraceful conduct by a few American troops who dishonoured our country and disregarded our values.' The abuse however did not constitute isolated cases but represented further proof of a widespread pattern.

- ^ a b c d e Scott A. Allen; Josiah D. Rich; Robert C. Bux; Bassina Farbenblum; Matthew Berns; Leonard Rubenstein (December 5, 2006). "Deaths of Detainees in the Custody of US Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan From 2002 to 2005". Medscape General Medicine. 8 (4): 46. PMC 1868355. PMID 17415327.

- ^ "Abu Ghraib: Iraqi victims' case against US contractor ends in mistrial". Al Jazeera. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ a b "Graner gets 10 years for Abu Ghraib abuse". NBC News. Associated Press. January 6, 2005. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Dickerscheid, P.J. (June 29, 2009). "Abu Ghraib scandal haunts W.Va. reservist". The Independent (Ashland, Kentucky). Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020.

- ^ Eric Schmitt; Thom Shanker (July 26, 2005). "U.S. Officials Retool Slogan for Terror War". The New York Times.

- ^ Bazinet, Kenneth R. (September 17, 2001). "A Fight Vs. Evil, Bush And Cabinet Tell U.S." Daily News. New York. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ "President: Today We Mourned, Tomorrow We Work". georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. Archived from the original on August 25, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "President Declares "Freedom at War with Fear"". georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "Transcript of President Bush's address". CNN. September 20, 2001. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Text: President Bush Addresses the Nation". The Washington Post. September 20, 2001. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "Iraq war illegal, says Annan". BBC News. September 16, 2004. Archived from the original on September 12, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ "A chronology of the six-week invasion of Iraq". PBS. February 26, 2004. Archived from the original on March 31, 2008. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- ^ a b "Iraq War". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 16, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Hersh, Seymour (April 30, 2004). "Torture at Abu Ghraib". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 1, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ a b c Library (March 12, 2016). "Iraq Prison Abuse Scandal Fast Facts". CNN. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "U.S. Abuse of Iraqi Detainees at Abu Ghraib Prison". The American Journal of International Law. 98 (3): 591–596. July 2004. doi:10.2307/3181656. JSTOR 3181656. S2CID 229167851.

- ^ General (Dept. of the Army), Inspector (2004). Detainee Operations Inspection. Diane Publishing. pp. 23–24. ISBN 1-4289-1031-X.

- ^ "Detention | Costs of War". The Costs of War. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Hersh 2004, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Hersh 2004, p. 22.

- ^ Schooner, Steven L (2005). "Contractor Atrocities at Abu Ghraib: Compromised Accountability in a Streamlined, Outsourced Government". Policy Review. 16: 25. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Iraq: Human rights must be foundation for rebuilding" (PDF). Amnesty International. June 20, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ "Iraq: Continuing failure to uphold human rights" (PDF). Amnesty International. July 23, 2003. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Hanley, Charles J. (November 1, 2003). "AP Enterprise: Former Iraqi detainees tell of riots, punishment in the sun, good Americans and pitiless ones". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on May 3, 2014. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Sjoberg, Laura; Gentry, Caron E. (2007). Mothers, Monsters, Whores. New York, USA: Zed Books. pp. 58–87. ISBN 978-1-84277-866-1.

- ^ a b Greenberg & Dretel 2005, p. xiii.

- ^ "Request for Guidance rearding OGC EC, dated 5/19/04" (PDF). May 19, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ^ "American Civil Liberties Union: ACLU Interested Persons Memo on FBI documents concerning detainee abuse at Guantanamo Bay". ACLU. July 12, 2005. Archived from the original on October 17, 2009. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ Smith, R. Jeffrey; White, Josh (June 12, 2004). "General Granted Latitude At Prison". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007.

- ^ "Wrong advice blamed for US abuse". BBC News Americas. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. June 17, 2006. Archived from the original on January 4, 2007. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

most defendants say they were following orders.

- ^ "US memo shows Iraq jail methods". BBC News Americas. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. March 30, 2005. Archived from the original on May 26, 2006. Retrieved February 3, 2007.

The top US general in Iraq authorised interrogation techniques including the use of dogs, stress positions and disorientation, a memo has shown.

- ^ Worden, Leon (July 2, 2004). "Karpinski: Rumsfeld OK'd Methods at Abu Ghraib". Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 4, 2004. Retrieved July 4, 2004.

- ^ "Rumsfeld approved Iraq interrogation methods: report". abc.net.au. Reuters. May 15, 2004. Archived from the original on October 10, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Rumsfeld okayed abuses says former U.S. general". Reuters. November 25, 2006. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2016.

- ^ "Accountability for U.S. Torture: Germany". CCR. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ "Rumsfeld okayed abuses says former U.S. Army general". AlertNet. Reuters News. March 30, 2012. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008. Retrieved April 3, 2012.

- ^ "German Court War Crimes Litigation Against Donald Rumsfeld". Class Action World. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ "German Case Again Donald Rumsfeld filed by CCR". Center for Constitutional Rights. Archived from the original on May 16, 2015. Retrieved March 31, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Mayer, Jane (November 14, 2005). "A Deadly Interrogation: Can the C.I.A. legally kill a prisoner?". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 2, 2014. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ Perry, Tony (May 28, 2005). "SEAL Officer Not Guilty of Assaulting Iraqi". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ McChesney, John (October 27, 2005). "The Death of an Iraqi Prisoner". NPR. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Shane, Scott (August 30, 2012). "No Charges Filed on Harsh Tactics Used by the C.I.A." The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 22, 2019. Retrieved January 25, 2013.

- ^ Otterman, Sharon. "Did the mistreatment of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib amount to torture?". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ Taguba, Antonio (May 2004). "The "Taguba Report" On Treatment Of Abu Ghraib Prisoners In Iraq". Findlaw.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Gardham, Duncan; Cruickshank, Paul (May 28, 2009). "Abu Ghraib abuse photos 'show rape'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on August 25, 2014. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c Higham, Scott; Stephens, Joe (May 21, 2004). "New Details of Prison Abuse Emerge". The Washington Post. p. A01. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

Hilas also said he witnessed an Army translator having sex with a boy at the prison.

- ^ Harding, Luke (September 20, 2004). "After Abu Ghraib". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016.

- ^ Harding, Luke (May 12, 2004). "Focus shifts to jail abuse of women". The Guardian. florida. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016.

- ^ Tencer, Daniel (September 11, 2010). "Journalist: Women raped at Abu Ghraib were later 'honor killed'". Raw Story. Archived from the original on July 29, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ Hersh, Seymour; Sealey, Geraldine (July 15, 2004). "Hersh: Children sodomized at Abu Ghraib, on tape". Salon. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved December 15, 2014.

- ^ Kate Zernike (January 12, 2005). "Detainees Depict Abuses by Guard in Prison in Iraq". The New York Times.

- ^ Chamberlain, Gethin (May 13, 2004). "Chilling new evidence of the brutal regime at Iraqi prison". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014.

- ^ Redeker, Bill (January 7, 2006). "Former Iraqi Prisoners Recount Abuse – Former Iraqi Prisoners Recount Mistreatment by U.S. Soldiers". ABC News. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ "Red Cross saw 'widespread abuse'". BBC News. May 8, 2004. Archived from the original on July 22, 2004.

- ^ Worthington, Andy. "Andy Worthington's Interview about Guantánamo and Torture for Columbia University's Rule of Law Oral History Project". andyworthington.co.uk (Interview). Archived from the original on February 11, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Leigh, David (May 8, 2004). "UK forces taught torture methods". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on May 30, 2004.

- ^ McCoy, Alfred W. (2006). A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. Holt. ISBN 9781429900683.

- ^ Adams, Phillip (March 16, 2006). "A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, From the Cold War to the War on Terror". Late Night Live. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Doyle, Robert C. (2010). The Enemy in Our Hands: America's Treatment of Prisoners of War from the Revolution to the War on Terror. University Press of Kentucky. p. 319. ISBN 978-0813139616.

- ^ Zagorin, Adam (May 18, 2007). "Shell-Shocked at Abu Ghraib?". Time. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Hanley, Charles J. (November 1, 2003). "AP Enterprise: Former Iraqi detainees tell of riots, punishment in the sun, good Americans and pitiless ones". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ a b Hanley, Charles J. (May 9, 2004). "Early accounts of extensive Iraq abuse met U.S. silence". Southeast Missourian. Archived from the original on July 1, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- ^ Mitchell, Greg (May 8, 2008). "Four Years Later: Why Did It Take So Long for the Press to Break Abu Ghraib Story?". Editor & Publisher. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2013.