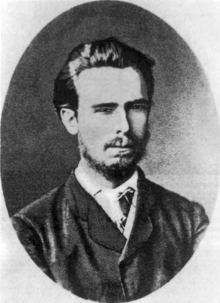

Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev (Russian: Серге́й Генна́диевич Неча́ев) (2 October [O.S. 20 September] 1847 – 3 December [O.S. 21 November] 1882) was a Russian anarcho-communist,[1] part of the Russian nihilist movement, known for his single-minded pursuit of revolution by any means necessary, including revolutionary terror.[2]

Sergey Nechayev | |

|---|---|

| Сергей Нечаев | |

| |

| Born | Sergey Gennadiyevich Nechayev 2 October 1847 |

| Died | 3 December 1882 (aged 35) |

| Known for | |

| Movement | Narodniks, Russian nihilist movement |

Nechayev fled Russia in 1869 after having been involved in the murder of a former comrade—Ivan Ivanov, who disagreed with some actions of Nechayervites. Complicated relationships with fellow revolutionaries caused him to be expelled from the International Workingmen's Association. Arrested in Switzerland in 1872, he was extradited back to Russia where he received a twenty-year sentence and died in prison.

Early life in Russia

editNechayev was born in Ivanovo, then a small textile town, to poor parents—his father was a waiter and sign painter. His mother died when he was eight. His father remarried and had two more sons. They lived in a three-room house with his two sisters and grandparents. They were ex-serfs who had moved to Ivanovo. He had already developed an awareness of social inequality and a resentment of the local nobility in his youth. At the age of 10, he had learned his father's trades—waiting at banquets and painting signs. His father got him a job as an errand boy in a factory, but he refused the servant's job. His family paid for good tutors who taught him Latin, German, French, history, mathematics and rhetoric.[3]

Aged 18, Nechayev moved to Moscow, where he worked for the historian Mikhael Pogodin. A year later, he moved to Saint Petersburg, passed a teacher's exam and began teaching at a parish school. From September 1868, Nechayev attended lectures at the Saint Petersburg University as an auditor (he was never enrolled) and became acquainted with the subversive Russian literature of the Decembrists, the Petrashevsky Circle and Mikhail Bakunin among others as well as the growing student unrest at the university. Nechaev was even said to have slept on bare wood and lived on black bread in imitation of Rakhmetov, the ascetic revolutionary in Nikolay Chernyshevsky's novel What Is to Be Done?.[4]

Inspired by the failed attempt on the Tsar's life by Dmitry Karakozov, Nechayev participated in student activism in 1868–1869, leading a radical minority with Pyotr Tkachev and others.[5] Nechayev took part in devising this student movement's "Program of revolutionary activities" which stated later a social revolution as its ultimate goal. The program also suggested ways for creating a revolutionary organization and conducting subversive activities. In particular, the program envisioned composition of the Catechism of a Revolutionary, for which Nechayev would become famous.

In December 1868, Nechayev met Vera Zasulich (who would make an assassination attempt on General Fyodor Trepov, governor of Saint Petersburg in 1878) at a teachers' meeting. He asked her to come to his school where he held candlelit readings of revolutionary tracts. He would place pictures of Maximilien Robespierre and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just on the table while reading.[6] At these meetings, he plotted to assassinate Tsar Alexander II on the 9th anniversary of serfdom's abolition. The last of these student meetings occurred on 28 January 1869, where Nechayev presented a petition calling for freedom of assembly for students.[7]

Geneva exiles

editIn January 1869, Nechayev spread false rumors of his arrest in Saint Petersburg, then left for Moscow before heading abroad. He tried to get Vera Zasulich to emigrate with him by declaring love for her, but she refused.[8] He sent her a letter claiming to have been arrested. In Geneva, Switzerland, he pretended to be a representative of a revolutionary committee who had fled from the Peter and Paul Fortress and won the confidence of revolutionary-in-exile Mikhail Bakunin (who called him "my boy")[9] and his friend and collaborator Nikolai Ogarev.[10] Bakunin saw in Nechayev the authentic voice of Russian youth which he regarded as "the most revolutionary in the world".[11]

Nechayev, Bakunin and Ogarev organized a propaganda campaign of subversive material to be sent to Russia,[12] financed by Ogarev from the so-called Bakhmetiev Fund which had been intended for subsidizing their own revolutionary activities. Alexander Herzen disliked Nechayev's fanaticism and strongly opposed the campaign, believing Nechayev was influencing Bakunin toward more extreme rhetoric. However, Herzen relented to hand over much of the fund to Nechayev which he was to take to Russia to mobilise support for the revolution. Nechayev had a list of 387 people who were sent 560 parcels of leaflets for distribution April–August 1869.[13] The idea was that the activists would be caught, punished and radicalized. Amongst these people was Zasulich, who got five years exile because of a crudely coded letter sent by Nechayev.

Catechism of a Revolutionary

editIn late spring 1869, Nechayev wrote the Catechism of a Revolutionary, a program for the "merciless destruction" of society and the state. The main principle of the revolutionary catechism—the ends justify the means—became Nechayev's slogan throughout his revolutionary career. He saw ruthless immorality in the pursuit of total control by church and the state and believed that the struggle against them must therefore be carried out by any means necessary, with an unwavering focus on their destruction. The individual self is to be subsumed by a greater purpose in a kind of spiritual asceticism which for Nechayev was far more than just a theory, but the guiding principle by which he lived his life, claiming:

A revolutionary is a doomed man. He has no private interests, no affairs, sentiments, ties, property nor even a name of his own. His entire being is devoured by one purpose, one thought, one passion – the revolution. Heart and soul, not merely by word but by deed, he has severed every link with the social order and with the entire civilized world; with the laws, good manners, conventions, and morality of that world. He is its merciless enemy and continues to inhabit it with only one purpose – to destroy it.

A revolutionary "must infiltrate all social formations including the police. He must exploit rich and influential people, subordinating them to himself. He must aggravate the miseries of the common people, so as to exhaust their patience and incite them to rebel. And, finally, he must ally himself with the savage word of the violent criminal, the only true revolutionary in Russia".[14]

The book was to influence generations of radicals and was re-published by the Black Panther Party in 1969, one hundred years after its original publication. It also influenced the formation of the militant Red Brigades in Italy the same year.[15]

Return to Russia

editHaving left Russia illegally, Nechayev had to sneak back to Moscow via Romania in August 1869 with help from Bakunin's underground contacts. On the way, he met Hristo Botev, a Bulgarian revolutionary.[16] In Moscow, he lived an austere life, spending the fund only on political activities. He pretended to be a proxy of the Russian department of the Worldwide Revolutionary Union which did not exist and created an affiliate of a secret society called People's Reprisal Society (Russian: Общество народной расправы, romanized: Obshchestvo narodnoy raspravy) which issued the magazine People's Reprisal (Russian: Народная расправа, romanized: Narodnaya rasprava). He claimed that the society had existed for quite some time in every corner of Russia. He spoke passionately to student dissidents about the need to organise. Marxist writer Vera Zasulich (whose sister Alexandra sheltered him in Moscow) recalls that when she first met Nechayev, he immediately tried to recruit her, telling her about his plans:

- I felt terrible: it was really painful for me to say "That's unlikely...," "I don't know about that...." I could see that he was very serious, that this was no idle chatter about revolution. He could and would act – wasn't he the ringleader of the students?... I could imagine no greater pleasure than serving the revolution. I had dared only to dream of it, and yet now he was saying that he wanted to recruit me, that otherwise he wouldn't have thought of saying anything.... And what did I know of "the people"? I knew only the house serfs of Biakolovo and the members of my weaving collective, while he was himself a worker by birth.[17]

Many were impressed by the young proletarian and joined the group. However, the already fanatical Nechayev appeared to be becoming more distrustful of the people around him, even denouncing Bakunin as doctrinaire, "idly running off at the mouth and on paper". One Narodnaya Rasprava member, I. I. Ivanov, disagreed with Nechayev about the distribution of propaganda and left the group. On 21 November 1869, Nechayev and several comrades beat, strangled and shot Ivanov, hiding the body in a lake through a hole in the ice.[18]

The body was soon found and some of his colleagues arrested, but Nechayev eluded capture and in late November left for Saint Petersburg, where he tried to continue his activities to create a clandestine society. On 15 December 1869, he fled the country, heading back to Geneva. This incident was fictionalised by writer Fyodor Dostoevsky in his anti-nihilistic novel Demons (published three years later) in which the character Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky is based on Nechayev.[19]

Downfall

editBakunin and Ogarev embraced Nechayev on his return to Switzerland in January 1870, with Bakunin writing: "I so jumped for joy that I nearly smashed the ceiling with my old head!".[20] Soon after their reunion, Herzen died (21 January 1870) and a large fund from his personal wealth became available to Nechayev to continue his political activities. Nechayev issued a number of proclamations aimed at different strata of the Russian population.[21] Together with Ogarev, he published the Kolokol magazine (April–May, 1870, issues 1 to 6).[22] In his article "The Fundamentals of the Future Social System" (Glavnyye osnovy budushchego obshchestvennogo stroya), published in the People's Reprisal (1870, no. 2), Nechayev shared his vision of a socialist system which Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels would later term barracks communism.[23]

Nechayev's suspicion of his comrades had grown even greater, and he began stealing letters and private papers with which to blackmail Bakunin and his fellow exiles should the need arise.[24] He enlisted the help of Herzen's daughter Natalie. While not clearly breaking with Nechayev, Bakunin rebuked Nechayev upon discovery of his duplicity, saying: "Lies, cunning [and] entanglement [are] a necessary and marvelous means for demoralising and destroying the enemy, though certainly not a useful means of obtaining and attracting new friends". Bakunin then threatened Nechayev with breaking relations with him, writing:

According to your way of thinking, you are nearer to the Jesuits than to us. You are a fanatic. This is your enormous and peculiar strength. But at the same time this is your blindness, and blindness is a great and fatal weakness; blind energy errs and stumbles, and the more powerful it is, the more inevitable and serious are the blunders. You suffer from an enormous lack of the critical sense without which it is impossible to evaluate people and situations, and to reconcile means with ends. [...]

As a consequence of these considerations and in spite of all that has happened between us, I would wish not only to remain allied with you, but to make this union even closer and firmer, on condition that you will change the system entirely and will make mutual trust, sincerity and truth the foundation of our future relations. Otherwise the break between us is inevitable.[25]

The General Council of the foremost left-wing organisation, the International Workingmen's Association of 1864–1876, officially dissociated themselves from Nechayev, claiming he had abused the name of the organisation. After writing a letter to a publisher on Bakunin's behalf, threatening to kill the publisher if he did not release Bakunin from a contract, Nechayev became even more isolated from his comrades.[26] Bakunin continued to write privately to Nechayev, proposing that they continue to work together.[27]

In September 1870, Nechayev published an issue of the Commune magazine in London as the Second French Empire of Napoleon III collapsed. Hiding from the Okhrana, he went underground in Paris and then in Zürich. He also kept in touch with the Polish Blanquists such as Caspar Turski and others. In September 1872, Karl Marx produced the threatening letter (which Nechayev had written to the publisher) at the Hague Congress of the International at which Bakunin was also expelled from the organisation.[28]

On 14 August 1872, Nechayev was arrested in Zürich and handed over to the Russian police.[29] He was found guilty on 8 January 1873 and sentenced to twenty years of katorga (hard labor) for killing Ivanov. This was effectively a death sentence, since nobody survived twenty years in the Peter and Paul Fortress.[30] While locked up in a ravelin of the fortress, Nechayev managed to win over his guards with the strength of his convictions and by the late 1870s was using them to pass on correspondence with revolutionaries on the outside.[31] In December 1880, Nechayev established contact with the executive committee of the People's Will (Narodnaya Volya) and proposed a plan for his own escape. However, Narodnaya Volya abandoned the plan due to its unwillingness to distract the efforts of its members from attempting to assassinate Tsar Alexander II, which they achieved only in March 1881.[32]

Vera Zasulich, who ten years earlier had been among those investigated for Ivanov's murder, heard in 1877 that the head of the Saint Petersburg police, General Trepov, had ordered the flogging of Arkhip Bogolyubov, a young political prisoner. Though not a follower of Nechayev, Zasulich felt outraged at Bogolyubov's mistreatment and at the plight of other political prisoners. On 5 February, she walked into Trepov's office and shot and wounded him. In an indication of the popular political feeling of the time, a jury found her not guilty on the grounds that she had acted out of noble intent.

In November 1882, Nechayev died in his cell.[33] Despite his personal courage and fanatical dedication to the revolutionary cause, Nechayev's methods (later called Nechayevshchina) were viewed to have caused harm to the Russian revolutionary movement by endangering clandestine organizations. Historian Edvard Radzinsky suggests that many revolutionaries have successfully implemented Nechayev's methods and ideas, including Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.[14]

Influence

editNechayev's theories had a major influence on other Russian revolutionaries, like Pyotr Tkachev and Vladimir Lenin. He was the first to bring the theme of the professional revolutionary in Russia. Lenin's brother Aleksandr Ulyanov was part of an organization which based its program on Nechayev's. Lenin stated that Nechayev was a "Titan of the revolution" and that all of the communist revolutionaries must "read Nechayev".[34][35][36] Many critics inside and out of the Soviet Union labelled his version of revolutionary socialism the one that was taking place in the Soviet Union itself, with Soviet politicians after the Stalin era admitting this themselves many times. He also influenced later generations of Russian revolutionary nihilists.[37][38][39] He was rehabilitated during Stalin's time.[40]

The murder of Ivanov was the initial inspiration for Fyodor Dostoevsky's novel Demons. The character of Pyotr Stepanovich Verkhovensky, an organizer of a revolutionary group, was inspired by Nechayev and the ideas in Catechism of a Revolutionary. The character of Shatov in the novel was partially based on Ivanov.[41]

Notes

edit- ^ Gerlach, Christian; Six, Clemans, eds. (2020). The Palgrave Handbook of Anti-Communist Persecutions. Springer International Publishing. p. 122. ISBN 978-3030549633.

- ^ Maegd-Soëp, Carolina (1990). Trifonov and the Drama of the Russian Intelligentsia. Ghent State University, Russian Institute. p. 79. ISBN 978-90-73139-04-6.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 90.

- ^ Drozd, Andrew Michael (2012). Chernyshevskii's What is to be Done?: A Reevaluation. p. 115.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 149.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 93.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 97.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 101.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 111.

- ^ a b Radzinsky, Edvard (1997). Stalin: The First In-depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives. ISBN 0-385-47954-9.

- ^ Avrich 1988, p. 51.

- ^ Siljak 2009, p. 120.

- ^ Engel, Barbara Alpern; Rosenthal, Clifford (2013). Five Sisters: Women Against the Tsar. Cornell University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-5017-5699-3.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Bloom, Harold (1989). Fydoro Dostoevsky. p. 60

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 162.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Bakunin, Mikhail. "M. Bakunin to Sergey Nechayev". In Confino, Michael (1974). Daughter of a Revolutionary: Natalie Herzen and the Bakunin-Nechayev Circle. London: Alcove Press.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 164.

- ^ Wheen, Francis (1999). Karl Marx pp. 346–347.

- ^ Fernbach, David, ed. (1974). Marx: The First International and After p. 49

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 165.

- ^ Hyams

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2014, p. 169.

- ^ Clellan, Woodford Mc (1973). "Nechaevshchina: An Unknown Chapter". Slavic Review. 32 (3): 546–553. doi:10.2307/2495409. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2495409.

- ^ Mayer, Robert (1993). "Lenin and the Concept of the Professional Revolutionary". History of Political Thought. 14 (2): 249–263. ISSN 0143-781X. JSTOR 26214357.

- ^ "The Influences of Chernyshevsky, Tkachev, and Nechaev on the political thought of V.I. Lenin". Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ "Сергей Нечаев: "темный чуланчик" русской революции". МирТесен - рекомендательная социальная сеть (in Russian). Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- ^ Kimball, Alan (1973). "The First International and the Russian Obshchina". Slavic Review. 32 (3): 491–514. doi:10.2307/2495406. ISSN 0037-6779. JSTOR 2495406. S2CID 164131867.

- ^ Read, Cristopher (2004). Lenin: A Revolutionary Life.

- ^ Souvarine, Boris (1939). "A Critical Survey of Bolshevism". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Frank, Joseph (2010). Dostoevsky: A Writer In His time. Princeton University Press. pp. 630, 656.

References

edit- Avrich, Paul (1988). "Bakunin and Nechayev". Anarchist Portraits. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 32–52. ISBN 978-0-691-04753-9. OCLC 17727270.

- Hyams, Edward (1975). Terrorists and Terrorism. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-046-00786-3-4. LCCN 72-87111.

- Nomad, Max (1961) [1939]. "The Fanatic: Sergei Nechayev, The Possessed". Apostles of Revolution. New York: Collier Books. pp. 214–256. LCCN 61018566. OCLC 984463383.

- Payne, Robert (1967). The Fortress. London: W. H. Allen & Co. OCLC 12134096.

- Payne, Robert (1975). "The Coming of the Dark Ages". The Corrupt Society. New York: Praeger. pp. 193–297. ISBN 0-275-51020-4. LCCN 73-11782.

- Pomper, Phillip (1976). "Bakunin, Nechaev and the "Catechism of a Revolutionary": The Case for Joint Authorship". Canadian-American Slavic Studies. 10 (4): 534–551. doi:10.1163/221023976X00053. ISSN 2210-2396.

- Prawdin, Michael (1961). The Unmentionable Nechaev: A Key to Bolshevism. London: Allen & Unwin. OCLC 585156.

- Siljak, Ana (2009). Angel of Vengeance: The Girl Who Shot the Governor of St. Petersburg and Sparked the Age of Assassination. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-36401-4. LCCN 2007042758. OCLC 461268649.

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2014) [1956]. "Force and Fraud". Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 149–169. ISBN 978-0691610412. OCLC 890439998.

External links

edit- Nechayev, Sergey (1869). The Revolutionary Catechism.