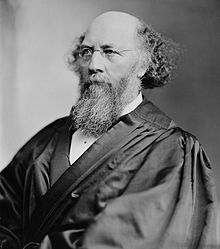

Stephen Johnson Field (November 4, 1816 – April 9, 1899) was an American jurist. He was an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court from May 20, 1863, to December 1, 1897, the second longest tenure of any justice. Prior to this appointment, he was the fifth Chief Justice of California.

Stephen Johnson Field | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| In office May 20, 1863 – December 1, 1897 | |

| Nominated by | Abraham Lincoln |

| Preceded by | Seat established |

| Succeeded by | Joseph McKenna |

| 5th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of California | |

| In office September 12, 1859 – May 20, 1863 | |

| Nominated by | John B. Weller |

| Preceded by | David S. Terry |

| Succeeded by | Warner Cope |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of California | |

| In office October 13, 1857 – September 12, 1859 | |

| Nominated by | J. Neely Johnson |

| Preceded by | Hugh Murray |

| Succeeded by | Edwin B. Crocker |

| Member of the California State Assembly from the 14th district | |

| In office 1851–1852 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | A. G. Caldwell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 4, 1816 Haddam, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Died | April 9, 1899 (aged 82) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Resting place | Rock Creek Cemetery Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Sue Virginia Swearingen

(m. 1859) |

| Education | Williams College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Early life and education

editBorn in Haddam, Connecticut, he was the sixth of the nine children of David Dudley Field I, a Congregationalist minister, and his wife Submit Dickinson, a teacher. His family produced three other children of major prominence in 19th century America: David Dudley Field II the prominent attorney, Cyrus Field, the millionaire investor and creator of the Atlantic Cable, and Rev. Henry Martyn Field, a prominent clergyman and travel writer. He grew up in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and went to Turkey at thirteen with his sister Emilia and her missionary husband, Rev. Josiah Brewer. He received a B.A. from Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1837. While attending Williams College he was one of the original Founders of Delta Upsilon fraternity. After reading law in Albany with Harmanus Bleecker and New York City with his brother David, Stephen was admitted to the bar. He practiced law with David until 1848, when he went to California during the Gold Rush.[1]

Field was an uncle of future Associate Justice David Josiah Brewer. Other notable relatives include Paul Stephen Field and legal scholar Anne Field.

Career in California politics and law

editIn California, Field's legal practice boomed and he was elected alcalde, a form of mayor and justice of the peace under the old Mexican rule of law, of Marysville (curiously, he was elected Alcalde just three days after his arrival in Marysville).[2] Because the Gold Rush city could not afford a jail, and it cost too much to transport prisoners to San Francisco, Field implemented[clarification needed] the whipping post, believing that without such a brutal implement many in the rough and tumble city would be hanged for minor crimes. The voters sent him to the California State Assembly in 1850 to represent Yuba County, but he lost a race the next year for the State Senate. His successful legal practice led to his election to the California Supreme Court in 1857, serving six years.[3]

Field was determined and vengeful when others disagreed with him, and he easily made enemies. An opponent of his wrote that Field's life would be "found to be one series of little-mindedness, meanlinesses, of braggadocio, pusillanimity, and contemptible vanity."[4]

While serving on the California Supreme Court, Field had a special coat made with pockets large enough to hold two pistols so that he could fire the weapons inside the pockets.[5] In 1858 he was challenged to a duel by a fellow Judge (William T. Barbour) but at the dueling ground, neither man fired his gun.[6]

In 1859 Field replaced the former chief justice of the California Supreme Court, David S. Terry, because Judge Terry killed a United States Senator from California (David Colbreth Broderick) in a duel and left the state.[7] Field and Terry's paths crossed again 30 years later when Field, acting in his capacity as a circuit judge of the 9th Federal Circuit Court, ruled against Terry in a convoluted divorce case (and had him sent to jail for contempt of court as well). Seeking revenge, Terry attempted to kill Field in 1889 near Stockton, California, but was instead shot dead by Field's bodyguard, U.S. Marshal David B. Neagle. Legal issues arising from the killing of Terry came before the Supreme Court in the 1890 habeas corpus case of In re Neagle.[8] The Court ruled the United States Attorney General had authority to appoint U.S. Marshals as bodyguards to Supreme Court justices and Marshal Neagle had acted within the scope of his authority in shooting Terry. Field recused himself from the case.[9]

U.S. Supreme Court justice

editThe number of seats on the United States Supreme Court was expanded from nine to ten in March 1863, as a result of the Tenth Circuit Act.[10] This gave President Abraham Lincoln an opportunity to nominate a new associate justice, which he did on March 6, 1863.[11] Seeking to effect both a regional and political balance on the Court, Lincoln selected Field, a westerner and Unionist Democrat.[12] Field was confirmed by the United States Senate on March 10, 1863,[11] and took the judicial oath of office on May 20, 1863.[13]

Field insisted on breaking John Marshall's record of 34 years on the court, even when he was no longer able to handle the workload. His colleagues asked him to resign due to his being intermittently senile,[14] but he refused, at one point John Marshall Harlan urged Field to retire, reminding Field that he had been part of a committee to urge Justice Robert Grier to retire. Finding Field dozing in the robing room, Harlan later related what happened next: “The old man listened, gradually became alert, and finally, with his eyes blazing with the fire of youth, he burst out, ‘Yes, and a dirtier day’s work I never did in my life.'”[15]

In March 1896, he wrote what would be his final opinion on behalf of the Court, but remained on the bench for another twenty months, finally retiring on December 1, 1897.[16] Field would become the last veteran of both the Taney Court and the Chase Court to remain on the bench. He would remain the longest serving member of the Court until his record was surpassed by William O. Douglas, who served from 1939 to 1975.

He died in Washington, D.C., on April 9, 1899, and was buried there in the Rock Creek Cemetery.[17]

Jurisprudence

editField wrote 544 opinions, more than any other justice save for Justice Samuel Miller, John P. Stevens,[18] and Clarence Thomas[19] (by comparison, Chief Justice Marshall wrote 508 opinions in his 34 years on the court).[20] According to journalist Brian Doherty, "Field was one of the pioneers of the concept (beloved by many libertarian legal thinkers) of substantive due process – the notion that the due process protected by the Fourteenth Amendment applied not merely to procedures but to the substance of laws as well."[21] Field's vocal advocacy of substantive due process was illustrated in his dissents to the Slaughter-House Cases and Munn v. Illinois. In the Slaughter-House Cases, Justice Field's dissent focused on the Privileges or Immunities clause, not the Due Process clause (which was important in the dissent of Justice Bradley as well as the dissent of Justice Swayne). In both Munn v. Illinois and Mugler v. Kansas, Justice Field based his dissent on the protection of property interests by the Due Process clause. One of Field's most notable opinions was his majority opinion in Pennoyer v. Neff, which set the standard on personal jurisdiction for the next 100 years. His views on due process were eventually adopted by the court's majority after he left the Supreme Court. In other cases he helped end the income tax (Pollock v. Farmers' Loan and Trust Company), limited antitrust law (United States v. E.C. Knight Company), and limited the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission. He also joined the majority in Plessy v. Ferguson that upheld racial segregation. Field dissented in the landmark case Strauder v. West Virginia, where the majority opinion held that the exclusion of African-Americans from juries violated the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.

Early in his career, Field wrote opinions against California's laws discriminating against the Chinese immigrants to that state.[22] Serving as an individual jurist in district court, he notably struck down the so-called 'Pigtail Ordinance' in 1879, which was regarded as discriminating against Chinese, making him unpopular with the Californian public. In his 1884 district court ruling, In re Look Tin Sing, he declared that children born in U.S. jurisdictions are U.S. citizens regardless of ancestry.[23] However, as a member of the U.S. Supreme Court, he penned opinions infused with racist anti-Chinese-American rhetoric, most notably in his majority opinion in The Chinese Exclusion Case, Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889), and in his dissent in Chew Heong v. United States, 112 U.S. 536 (1884).

Academic work

editIn November 1885, Field served as an original trustee of Leland Stanford Junior University.[24]

See also

edit- Juristic person (Corporate personhood)

- Demographics of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Chase Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Fuller Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Taney Court

- List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Waite Court

- List of justices of the Supreme Court of California

- List of United States federal judges by longevity of service

References

edit- ^ McCloskey, Robert Green (1951). American Conservatism in the Age of Enterprise, 1865-1910. Harper & Row. pp. 86–92.

- ^ Tocklin, Adrian M. (1997). "Pennoyer v. Neff: The Hidden Agenda of Stephen J. Field". Seton Hall Law Review: 104.

- ^ McCloskey (1951), pp. 96–97.

- ^ "Stephen Johnson Field". Archived from the original on March 3, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Tocklin (1997), p. 102.

- ^ Tocklin (1997), p. 105.

- ^ Johnson, J. Edward (1963). History of the California Supreme Court: The Justices 1850–1900 (PDF). Vol. 1. San Francisco: Bender Moss Co. pp. 65–72. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 17, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ Gorham, George C. (2005). "The Story of the Attempted Assassination of Justice Field by a Former Associate on the Supreme Bench of California". Journal of the Supreme Court Historical Society. Vol. 30, no. 2. pp. 105–194. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5818.2005.00102.x.

- ^ "In the Matter of David Neagle". U.S. Marshals Service. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 10, 2017.

- ^ "Landmark Legislation: Tenth Circuit". Washington, D.C.: Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ a b McMillion, Barry J. (January 28, 2022). Supreme Court Nominations, 1789 to 2020: Actions by the Senate, the Judiciary Committee, and the President (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: Congressional Research Service. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Sandefur, Timothy (November 4, 2010). "Happy birthday, Stephen J. Field!". Sacramento, California: Pacific Legal Foundation. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Justices 1789 to Present". Washington, D.C.: Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Morris, Jeffrey B. (1981). "The Era of Mellville Weston Fuller". Supreme Court Historical Society 1981 Yearbook. Supreme Court Historical Society. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006.

- ^ "From Cover-Ups To Secret Plots: The Murky History Of Supreme Justices' Health". WAMU. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- ^ Garrowt, David J. (Autumn 2000). "Mental Decrepitude on the U.S. Supreme Court: The Historical Case for a 28th Amendment". The University of Chicago Law Review. 67 (4): 1009. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ Swisher, Carl Brent (1930). Stephen J. Field: Craftsman of the Law. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution. p. 449. Retrieved February 18, 2022 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ "A Look Back at Justice Stevens' Most Important Opinions - Law360". Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ "Clarence Thomas (Supreme Court) - Ballotpedia". Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- ^ Tocklin (1997), n. 174.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (2007). Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement. p. 28.

- ^ McCloskey (1951), pp. 109–111.

- ^ "In re Look Tin Sing (Ruling)" (PDF). libraryweb.uchastings.edu. Federal Reporter 21 F. 905, Circuit Court, D. California, September 29, 1884. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ "Leland Stanford Jr. University". Sonoma Democrat. November 28, 1885. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 16, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2017 – via California Digital Newspaper Collection.

Further reading

edit- Abraham, Henry J. (1992). Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Beatty, Jack (2007). Age of Betrayal: The Triumph of Money in America 1865–1900. Knopf.

- Cushman, Clare (2001). The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies, 1789–1995 (2nd ed.). (Supreme Court Historical Society, Congressional Quarterly Books). ISBN 1-56802-126-7.

- Frank, John P. (1995). Friedman, Leon; Israel, Fred L. (eds.). The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions. Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0-7910-1377-4.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- Kens, Paul (1997). Justice Stephen Field: Shaping Liberty from the Gold Rush to the Gilded Age. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0817-1.

- Martin, Fenton S.; Goehlert, Robert U. (1990). The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Books. ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Urofsky, Melvin I. (1994). The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 590. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1.

External links

edit- Oyez Project, Official Supreme Court media, Stephen Johnson Field.

- Stephen Johnson Field at PBS

- Stephen J. Field at Supreme Court Historical Society.

- Works by Stephen Johnson Field at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Stephen Johnson Field at the Internet Archive

- Guide to the Stephen Johnson Field Letters Addressed to Him, 1862-1896. at The Bancroft Library

- Past & Present Justices. California State Courts.