A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group.[1] This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross anatomy and mode of living from the ancestral group. These fossils serve as a reminder that taxonomic divisions are human constructs that have been imposed in hindsight on a continuum of variation. Because of the incompleteness of the fossil record, there is usually no way to know exactly how close a transitional fossil is to the point of divergence. Therefore, it cannot be assumed that transitional fossils are direct ancestors of more recent groups, though they are frequently used as models for such ancestors.[2]

In 1859, when Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species was first published, the fossil record was poorly known. Darwin described the perceived lack of transitional fossils as "the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory," but he explained it by relating it to the extreme imperfection of the geological record.[3] He noted the limited collections available at the time but described the available information as showing patterns that followed from his theory of descent with modification through natural selection.[4] Indeed, Archaeopteryx was discovered just two years later, in 1861, and represents a classic transitional form between earlier, non-avian dinosaurs and birds. Many more transitional fossils have been discovered since then, and there is now abundant evidence of how all classes of vertebrates are related, including many transitional fossils.[5] Specific examples of class-level transitions are: tetrapods and fish, birds and dinosaurs, and mammals and "mammal-like reptiles".

The term "missing link" has been used extensively in popular writings on human evolution to refer to a perceived gap in the hominid evolutionary record. It is most commonly used to refer to any new transitional fossil finds. Scientists, however, do not use the term, as it refers to a pre-evolutionary view of nature.

Evolutionary and phylogenetic taxonomy

editTransitions in phylogenetic nomenclature

editIn evolutionary taxonomy, the prevailing form of taxonomy during much of the 20th century and still used in non-specialist textbooks, taxa based on morphological similarity are often drawn as "bubbles" or "spindles" branching off from each other, forming evolutionary trees.[6] Transitional forms are seen as falling between the various groups in terms of anatomy, having a mixture of characteristics from inside and outside the newly branched clade.[7]

With the establishment of cladistics in the 1990s, relationships commonly came to be expressed in cladograms that illustrate the branching of the evolutionary lineages in stick-like figures. The different so-called "natural" or "monophyletic" groups form nested units, and only these are given phylogenetic names. While in traditional classification tetrapods and fish are seen as two different groups, phylogenetically tetrapods are considered a branch of fish. Thus, with cladistics there is no longer a transition between established groups, and the term "transitional fossils" is a misnomer. Differentiation occurs within groups, represented as branches in the cladogram.[8]

In a cladistic context, transitional organisms can be seen as representing early examples of a branch, where not all of the traits typical of the previously known descendants on that branch have yet evolved.[9] Such early representatives of a group are usually termed "basal taxa" or "sister taxa,"[10] depending on whether the fossil organism belongs to the daughter clade or not.[8]

Transitional versus ancestral

editA source of confusion is the notion that a transitional form between two different taxonomic groups must be a direct ancestor of one or both groups. The difficulty is exacerbated by the fact that one of the goals of evolutionary taxonomy is to identify taxa that were ancestors of other taxa. However, because evolution is a branching process that produces a complex bush pattern of related species rather than a linear process producing a ladder-like progression, and because of the incompleteness of the fossil record, it is unlikely that any particular form represented in the fossil record is a direct ancestor of any other. Cladistics deemphasizes the concept of one taxonomic group being an ancestor of another, and instead emphasizes the identification of sister taxa that share a more recent common ancestor with one another than they do with other groups. There are a few exceptional cases, such as some marine plankton microfossils, where the fossil record is complete enough to suggest with confidence that certain fossils represent a population that was actually ancestral to a later population of a different species.[11] But, in general, transitional fossils are considered to have features that illustrate the transitional anatomical features of actual common ancestors of different taxa, rather than to be actual ancestors.[2]

Prominent examples

editArchaeopteryx

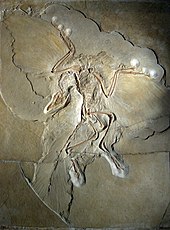

editArchaeopteryx is a genus of theropod dinosaur closely related to the birds. Since the late 19th century, it has been accepted by palaeontologists, and celebrated in lay reference works, as being the oldest known bird, though a study in 2011 has cast doubt on this assessment, suggesting instead that it is a non-avialan dinosaur closely related to the origin of birds.[12]

It lived in what is now southern Germany in the Late Jurassic period around 150 million years ago, when Europe was an archipelago in a shallow warm tropical sea, much closer to the equator than it is now. Similar in shape to a European magpie, with the largest individuals possibly attaining the size of a raven,[13] Archaeopteryx could grow to about 0.5 metres (1.6 ft) in length. Despite its small size, broad wings, and inferred ability to fly or glide, Archaeopteryx has more in common with other small Mesozoic dinosaurs than it does with modern birds. In particular, it shares the following features with the deinonychosaurs (dromaeosaurs and troodontids): jaws with sharp teeth, three fingers with claws, a long bony tail, hyperextensible second toes ("killing claw"), feathers (which suggest homeothermy), and various skeletal features.[14] These features make Archaeopteryx a clear candidate for a transitional fossil between dinosaurs and birds,[15] making it important in the study both of dinosaurs and of the origin of birds.

The first complete specimen was announced in 1861, and ten more Archaeopteryx fossils have been found since then. Most of the eleven known fossils include impressions of feathers—among the oldest direct evidence of such structures. Moreover, because these feathers take the advanced form of flight feathers, Archaeopteryx fossils are evidence that feathers began to evolve before the Late Jurassic.[16]

Australopithecus afarensis

editThe hominid Australopithecus afarensis represents an evolutionary transition between modern bipedal humans and their quadrupedal ape ancestors. A number of traits of the A. afarensis skeleton strongly reflect bipedalism, to the extent that some researchers have suggested that bipedality evolved long before A. afarensis.[17] In overall anatomy, the pelvis is far more human-like than ape-like. The iliac blades are short and wide, the sacrum is wide and positioned directly behind the hip joint, and there is clear evidence of a strong attachment for the knee extensors, implying an upright posture.[17]: 122

While the pelvis is not entirely like that of a human (being markedly wide, or flared, with laterally orientated iliac blades), these features point to a structure radically remodelled to accommodate a significant degree of bipedalism. The femur angles in toward the knee from the hip. This trait allows the foot to fall closer to the midline of the body, and strongly indicates habitual bipedal locomotion. Present-day humans, orangutans and spider monkeys possess this same feature. The feet feature adducted big toes, making it difficult if not impossible to grasp branches with the hindlimbs. Besides locomotion, A. afarensis also had a slightly larger brain than a modern chimpanzee[18] (the closest living relative of humans) and had teeth that were more human than ape-like.[19]

Pakicetids, Ambulocetus

editThe cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises) are marine mammal descendants of land mammals. The pakicetids are an extinct family of hoofed mammals that are the earliest whales, whose closest sister group is Indohyus from the family Raoellidae.[20][21] They lived in the Early Eocene, around 53 million years ago. Their fossils were first discovered in North Pakistan in 1979, at a river not far from the shores of the former Tethys Sea.[22][page needed] Pakicetids could hear under water, using enhanced bone conduction, rather than depending on tympanic membranes like most land mammals. This arrangement does not give directional hearing under water.[23]

Ambulocetus natans, which lived about 49 million years ago, was discovered in Pakistan in 1994. It was probably amphibious, and looked like a crocodile.[24] In the Eocene, ambulocetids inhabited the bays and estuaries of the Tethys Ocean in northern Pakistan.[25] The fossils of ambulocetids are always found in near-shore shallow marine deposits associated with abundant marine plant fossils and littoral molluscs.[25] Although they are found only in marine deposits, their oxygen isotope values indicate that they consumed water with a range of degrees of salinity, some specimens showing no evidence of sea water consumption and others none of fresh water consumption at the time when their teeth were fossilized. It is clear that ambulocetids tolerated a wide range of salt concentrations.[26] Their diet probably included land animals that approached water for drinking, or freshwater aquatic organisms that lived in the river.[25] Hence, ambulocetids represent the transition phase of cetacean ancestors between freshwater and marine habitat.

Tiktaalik

editTiktaalik is a genus of extinct sarcopterygian (lobe-finned fish) from the Late Devonian period, with many features akin to those of tetrapods (four-legged animals).[27] It is one of several lines of ancient sarcopterygians to develop adaptations to the oxygen-poor shallow water habitats of its time—adaptations that led to the evolution of tetrapods.[28] Well-preserved fossils were found in 2004 on Ellesmere Island in Nunavut, Canada.[29]

Tiktaalik lived approximately 375 million years ago. Paleontologists suggest that it is representative of the transition between non-tetrapod vertebrates such as Panderichthys, known from fossils 380 million years old, and early tetrapods such as Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, known from fossils about 365 million years old. Its mixture of primitive fish and derived tetrapod characteristics led one of its discoverers, Neil Shubin, to characterize Tiktaalik as a "fishapod."[30][31] Unlike many previous, more fish-like transitional fossils, the "fins" of Tiktaalik have basic wrist bones and simple rays reminiscent of fingers. They may have been weight-bearing. Like all modern tetrapods, it had rib bones, a mobile neck with a separate pectoral girdle, and lungs, though it had the gills, scales, and fins of a fish.[27] However in a 2008 paper by Boisvert at al. it is noted that Panderichthys, due to its more derived distal portion, might be closer to tetrapods than Tiktaalik, which might have independently developed similarities to tetrapods by convergent evolution.[32]

Tetrapod footprints found in Poland and reported in Nature in January 2010 were "securely dated" at 10 million years older than the oldest known elpistostegids[33] (of which Tiktaalik is an example), implying that animals like Tiktaalik, possessing features that evolved around 400 million years ago, were "late-surviving relics rather than direct transitional forms, and they highlight just how little we know of the earliest history of land vertebrates."[34]

Amphistium

editPleuronectiformes (flatfish) are an order of ray-finned fish. The most obvious characteristic of the modern flatfish is their asymmetry, with both eyes on the same side of the head in the adult fish. In some families the eyes are always on the right side of the body (dextral or right-eyed flatfish) and in others they are always on the left (sinistral or left-eyed flatfish). The primitive spiny turbots include equal numbers of right- and left-eyed individuals, and are generally less asymmetrical than the other families. Other distinguishing features of the order are the presence of protrusible eyes, another adaptation to living on the seabed (benthos), and the extension of the dorsal fin onto the head.[35]

Amphistium is a 50-million-year-old fossil fish identified as an early relative of the flatfish, and as a transitional fossil.[36] In Amphistium, the transition from the typical symmetric head of a vertebrate is incomplete, with one eye placed near the top-center of the head.[37] Paleontologists concluded that "the change happened gradually, in a way consistent with evolution via natural selection—not suddenly, as researchers once had little choice but to believe."[36]

Amphistium is among the many fossil fish species known from the Monte Bolca Lagerstätte of Lutetian Italy. Heteronectes is a related, and very similar fossil from slightly earlier strata of France.[37]

Runcaria

editA Middle Devonian precursor to seed plants has been identified from Belgium, predating the earliest seed plants by about 20 million years. Runcaria, small and radially symmetrical, is an integumented megasporangium surrounded by a cupule. The megasporangium bears an unopened distal extension protruding above the multilobed integument. It is suspected that the extension was involved in anemophilous pollination. Runcaria sheds new light on the sequence of character acquisition leading to the seed, having all the qualities of seed plants except for a solid seed coat and a system to guide the pollen to the seed.[38]

Fossil record

editNot every transitional form appears in the fossil record, because the fossil record is not complete. Organisms are only rarely preserved as fossils in the best of circumstances, and only a fraction of such fossils have been discovered. Paleontologist Donald Prothero noted that this is illustrated by the fact that the number of species known through the fossil record was less than 5% of the number of known living species, suggesting that the number of species known through fossils must be far less than 1% of all the species that have ever lived.[39]

Because of the specialized and rare circumstances required for a biological structure to fossilize, logic dictates that known fossils represent only a small percentage of all life-forms that ever existed—and that each discovery represents only a snapshot of evolution. The transition itself can only be illustrated and corroborated by transitional fossils, which never demonstrate an exact half-way point between clearly divergent forms.[40]

The fossil record is very uneven and, with few exceptions, is heavily slanted toward organisms with hard parts, leaving most groups of soft-bodied organisms with little to no fossil record.[39] The groups considered to have a good fossil record, including a number of transitional fossils between traditional groups, are the vertebrates, the echinoderms, the brachiopods and some groups of arthropods.[41]

History

editPost-Darwin

editThe idea that animal and plant species were not constant, but changed over time, was suggested as far back as the 18th century.[42] Darwin's On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, gave it a firm scientific basis. A weakness of Darwin's work, however, was the lack of palaeontological evidence, as pointed out by Darwin himself. While it is easy to imagine natural selection producing the variation seen within genera and families, the transmutation between the higher categories was harder to imagine. The dramatic find of the London specimen of Archaeopteryx in 1861, only two years after the publication of Darwin's work, offered for the first time a link between the class of the highly derived birds, and that of the more basal reptiles.[43] In a letter to Darwin, the palaeontologist Hugh Falconer wrote:

Had the Solnhofen quarries been commissioned—by august command—to turn out a strange being à la Darwin—it could not have executed the behest more handsomely—than in the Archaeopteryx.[44]

Thus, transitional fossils like Archaeopteryx came to be seen as not only corroborating Darwin's theory, but as icons of evolution in their own right.[45] For example, the Swedish encyclopedic dictionary Nordisk familjebok of 1904 showed an inaccurate Archaeopteryx reconstruction (see illustration) of the fossil, "ett af de betydelsefullaste paleontologiska fynd, som någonsin gjorts" ("one of the most significant paleontological discoveries ever made").[46]

The rise of plants

editTransitional fossils are not only those of animals. With the increasing mapping of the divisions of plants at the beginning of the 20th century, the search began for the ancestor of the vascular plants. In 1917, Robert Kidston and William Henry Lang found the remains of an extremely primitive plant in the Rhynie chert in Aberdeenshire, Scotland, and named it Rhynia.[47]

The Rhynia plant was small and stick-like, with simple dichotomously branching stems without leaves, each tipped by a sporangium. The simple form echoes that of the sporophyte of mosses, and it has been shown that Rhynia had an alternation of generations, with a corresponding gametophyte in the form of crowded tufts of diminutive stems only a few millimetres in height.[48] Rhynia thus falls midway between mosses and early vascular plants like ferns and clubmosses. From a carpet of moss-like gametophytes, the larger Rhynia sporophytes grew much like simple clubmosses, spreading by means of horizontal growing stems growing rhizoids that anchored the plant to the substrate. The unusual mix of moss-like and vascular traits and the extreme structural simplicity of the plant had huge implications for botanical understanding.[49]

Missing links

editThe idea of all living things being linked through some sort of transmutation process predates Darwin's theory of evolution. Jean-Baptiste Lamarck envisioned that life was generated constantly in the form of the simplest creatures, and strove towards complexity and perfection (i.e. humans) through a progressive series of lower forms.[50] In his view, lower animals were simply newcomers on the evolutionary scene.[51]

After On the Origin of Species, the idea of "lower animals" representing earlier stages in evolution lingered, as demonstrated in Ernst Haeckel's figure of the human pedigree.[52] While the vertebrates were then seen as forming a sort of evolutionary sequence, the various classes were distinct, the undiscovered intermediate forms being called "missing links."

The term was first used in a scientific context by Charles Lyell in the third edition (1851) of his book Elements of Geology in relation to missing parts of the geological column, but it was popularized in its present meaning by its appearance on page xi of his book Geological Evidences of the Antiquity of Man of 1863. By that time, it was generally thought that the end of the last glacial period marked the first appearance of humanity; Lyell drew on new findings in his Antiquity of Man to put the origin of human beings much further back. Lyell wrote that it remained a profound mystery how the huge gulf between man and beast could be bridged.[53] Lyell's vivid writing fired the public imagination, inspiring Jules Verne's Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) and Louis Figuier's 1867 second edition of La Terre avant le déluge ("Earth before the Flood"), which included dramatic illustrations of savage men and women wearing animal skins and wielding stone axes, in place of the Garden of Eden shown in the 1863 edition.[54]

The search for a fossil showing transitional traits between apes and humans, however, was fruitless until the young Dutch geologist Eugène Dubois found a skullcap, a molar and a femur on the banks of Solo River, Java in 1891. The find combined a low, ape-like skull roof with a brain estimated at around 1000 cc, midway between that of a chimpanzee and an adult human. The single molar was larger than any modern human tooth, but the femur was long and straight, with a knee angle showing that "Java Man" had walked upright.[55] Given the name Pithecanthropus erectus ("erect ape-man"), it became the first in what is now a long list of human evolution fossils. At the time it was hailed by many as the "missing link," helping set the term as primarily used for human fossils, though it is sometimes used for other intermediates, like the dinosaur-bird intermediary Archaeopteryx.[56][57]

While "missing link" is still a popular term, well-recognized by the public and often used in the popular media,[58] the term is avoided in scientific publications.[5] Some bloggers have called it "inappropriate";[59] both because the links are no longer "missing", and because human evolution is no longer believed to have occurred in terms of a single linear progression.[5][60]

Punctuated equilibrium

editThe theory of punctuated equilibrium developed by Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge and first presented in 1972[61] is often mistakenly drawn into the discussion of transitional fossils.[62] This theory, however, pertains only to well-documented transitions within taxa or between closely related taxa over a geologically short period of time. These transitions, usually traceable in the same geological outcrop, often show small jumps in morphology between extended periods of morphological stability. To explain these jumps, Gould and Eldredge envisaged comparatively long periods of genetic stability separated by periods of rapid evolution. Gould made the following observation concerning creationist misuse of his work to deny the existence of transitional fossils:

Since we proposed punctuated equilibria to explain trends, it is infuriating to be quoted again and again by creationists—whether through design or stupidity, I do not know—as admitting that the fossil record includes no transitional forms. The punctuations occur at the level of species; directional trends (on the staircase model) are rife at the higher level of transitions within major groups.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Freeman & Herron 2004, p. 816

- ^ a b Prothero 2007, pp. 133–135

- ^ Darwin 1859, pp. 279–280

- ^ Darwin 1859, pp. 341–343

- ^ a b c Prothero, Donald R. (1 March 2008). "Evolution: What missing link?". New Scientist. 197 (2645): 35–41. doi:10.1016/s0262-4079(08)60548-5. ISSN 0262-4079.

- ^ For example, see Benton 1997

- ^ Prothero 2007, p. 84.

- ^ a b Kazlev, M. Alan. "Amphibians, Systematics, and Cladistics". Palaeos. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Prothero 2007, p. 127.

- ^ Prothero 2007, p. 263.

- ^ Prothero, Donald R.; Lazarus, David B. (June 1980). "Planktonic Microfossils and the Recognition of Ancestors". Systematic Biology. 29 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1093/sysbio/29.2.119. ISSN 1063-5157.

- ^ Xing Xu; Hailu You; Kai Du; Fenglu Han (28 July 2011). "An Archaeopteryx-like theropod from China and the origin of Avialae". Nature. 475 (7357): 465–470. doi:10.1038/nature10288. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 21796204. S2CID 205225790.

- ^ Erickson, Gregory M.; Rauhut, Oliver W. M.; Zhonghe Zhou; et al. (9 October 2009). "Was Dinosaurian Physiology Inherited by Birds? Reconciling Slow Growth in Archaeopteryx". PLOS One. 4 (10): e7390. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7390E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007390. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 2756958. PMID 19816582.

- ^ Yalden, Derek W. (September 1984). "What size was Archaeopteryx?". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 82 (1–2): 177–188. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1984.tb00541.x. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ "Archaeopteryx: An Early Bird". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 18 October 2006.

- ^ Wellnhofer 2004, pp. 282–300

- ^ a b Lovejoy, C. Owen (November 1988). "Evolution of Human walking" (PDF). Scientific American. 259 (5): 82–89. Bibcode:1988SciAm.259e.118L. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1188-118. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 3212438.

- ^ "Australopithecus afarensis". Human Evolution. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Suwa, Gen; Simpson, Scott; Asfaw, Berhane (January 2000). "Jaws and teeth of Australopithecus afarensis from Maka, Middle Awash, Ethiopia". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 111 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(200001)111:1<45::AID-AJPA4>3.0.CO;2-I. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 10618588.

- ^ Northeastern Ohio Universities Colleges of Medicine and Pharmacy (21 December 2007). "Whales Descended From Tiny Deer-like Ancestors". Science Daily. Rockville, MD: ScienceDaily, LLC. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Gingerich & Russell 1981

- ^ Castro & Huber 2003

- ^ Nummela, Sirpa; Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, Sunil; et al. (12 August 2004). "Eocene evolution of whale hearing". Nature. 430 (7001): 776–778. Bibcode:2004Natur.430..776N. doi:10.1038/nature02720. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15306808. S2CID 4372872.

- ^ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, Ellen M.; Roe, Lois J.; et al. (20 September 2001). "Skeletons of terrestrial cetaceans and the relationship of whales to artiodactyls". Nature. 413 (6853): 277–281. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..277T. doi:10.1038/35095005. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11565023. S2CID 4416684.

- ^ a b c Thewissen, J. G. M.; Williams, Ellen M. (November 2002). "The Early Radiations of Cetacea (Mammalia): Evolutionary Pattern and Developmental Correlations". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 33: 73–90. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095426. ISSN 1545-2069.

- ^ Thewissen, J. G. M.; Bajpai, Sunil (December 2001). "Whale Origins as a Poster Child for Macroevolution". BioScience. 51 (12): 1037–1049. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1037:WOAAPC]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ^ a b Daeschler, Edward B.; Shubin, Neil H.; Jenkins, Farish A. Jr. (6 April 2006). "A Devonian tetrapod-like fish and the evolution of the tetrapod body plan". Nature. 440 (7085): 757–763. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..757D. doi:10.1038/nature04639. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16598249.

- ^ Clack, Jennifer A. (December 2005). "Getting a Leg Up on Land". Scientific American. 293 (6): 100–107. Bibcode:2005SciAm.293f.100C. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1205-100. ISSN 0036-8733. PMID 16323697.

- ^ Easton, John (23 October 2008). "Tiktaalik's internal anatomy explains evolutionary shift from water to land". University of Chicago Chronicle. 28 (3). ISSN 1095-1237. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (5 April 2006). "Scientists Call Fish Fossil the 'Missing Link'". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Shubin 2008

- ^ "Pectoral fin info". uu.diva-portal.org. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz; Szrek, Piotr; Narkiewicz, Katarzyna; et al. (7 January 2010). "Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland". Nature. 463 (7227): 43–48. Bibcode:2010Natur.463...43N. doi:10.1038/nature08623. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 20054388. S2CID 4428903.

- ^ "Four feet in the past: trackways pre-date earliest body fossils". Nature (Editor's summary). 463 (7227). 7 January 2010. ISSN 0028-0836.

- ^ Chapleau & Amaoka 1998, pp. 223–226

- ^ a b Minard, Anne (9 July 2008). "Odd Fish Find Contradicts Intelligent-Design Argument". National Geographic News. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 4 August 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ a b Friedman, Matt (10 July 2008). "The evolutionary origin of flatfish asymmetry". Nature. 454 (7201): 209–212. Bibcode:2008Natur.454..209F. doi:10.1038/nature07108. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 18615083. S2CID 4311712.

- ^ Gerrienne, Philippe; Meyer-Berthaud, Brigitte; Fairon-Demaret, Muriel; et al. (29 October 2004). "Runcaria, a Middle Devonian Seed Plant Precursor". Science. 306 (5697): 856–858. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..856G. doi:10.1126/science.1102491. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15514154. S2CID 34269432.

- ^ a b Prothero 2007, pp. 50–53

- ^ Isaak, Mark, ed. (5 November 2006). "Claim CC200: Transitional fossils". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ^ Donovan & Paul 1998

- ^ Archibald, J. David (August 2009). "Edward Hitchcock's Pre-Darwinian (1840) 'Tree of Life'" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 42 (3): 561–592. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.688.7842. doi:10.1007/s10739-008-9163-y. ISSN 0022-5010. PMID 20027787. S2CID 16634677.

- ^ Darwin 1859, Chapter 10.

- ^ Williams, David B. (September 2011). "Benchmarks: September 30, 1861: Archaeopteryx is discovered and described". EARTH. ISSN 1943-345X. Archived from the original on 7 May 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ^ Wellnhofer 2009

- ^ Leche 1904, pp. 1379–1380

- ^ Kidston, Robert; Lang, William Henry (27 February 1917). "XXIV.—On Old Red Sandstone Plants showing Structure, from the Rhynie Chert Bed, Aberdeenshire. Part I. Rhynia Gwynne-Vaughanii, Kidston and Lang". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 51 (3): 761–784. doi:10.1017/S0263593300006805. ISSN 0080-4568. OCLC 704166643. S2CID 251580286. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ Kerp, Hans; Trewin, Nigel H.; Hass, Hagen (2003). "New gametophytes from the Early Devonian Rhynie chert". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences. 94 (4): 411–428. doi:10.1017/S026359330000078X. ISSN 0080-4568. S2CID 128629425.

- ^ Andrews 1967, p. 32

- ^ Lamarck 1815–1822

- ^ Appel, Toby A. (Fall 1980). "Henri De Blainville and the Animal Series: A Nineteenth-Century Chain of Being". Journal of the History of Biology. 13 (2): 291–319. doi:10.1007/BF00125745. ISSN 0022-5010. JSTOR 4330767. S2CID 83708471.

- ^ Haeckel 2011, p. 216.

- ^ Bynum, William F. (Summer 1984). "Charles Lyell's Antiquity of Man and its critics". Journal of the History of Biology. 17 (2): 153–187. doi:10.1007/BF00143731. ISSN 0022-5010. JSTOR 4330890. S2CID 84588890.

- ^ Browne 2003, pp. 130, 218, 515.

- ^ Swisher, Curtis & Lewin 2001

- ^ Reader 2011

- ^ Benton, Michael J. (March 2001). "Evidence of Evolutionary Transitions". actionbioscience. Washington, D.C.: American Institute of Biological Sciences. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (19 May 2009). "Darwinius: It delivers a pizza, and it lengthens, and it strengthens, and it finds that slipper that's been at large under the chaise lounge [sic] for several weeks..." The Loom (Blog). Waukesha, WI: Kalmbach Publishing. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ Sambrani, Nagraj (10 June 2009). "Why the term 'missing links' is inappropriate". Biology Times (Blog). Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "Newly found fossils could link to human ancestor". CBC News. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 8 April 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

It's tempting to call the new species a 'missing link' between earlier species and modern humans, but scientists say the concept no longer applies, given new knowledge of human evolution. [...] Researchers now say the evolution of humans consisted of a number of diverse species in many branches, not a single smooth line from ape-like species to humans.

- ^ Eldredge & Gould 1972, pp. 82–115

- ^ Bates, Gary (December 2006). "That quote!—about the missing transitional fossils". Creation. 29 (1): 12–15. ISSN 0819-1530. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- Theunissen, Lionel (24 June 1997). "Patterson Misquoted: A Tale of Two 'Cites'". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ Gould 1980, p. 189.

Sources

edit- Andrews, Henry N. Jr. (1967) [Originally published 1961]. Studies in Paleobotany. Chapter on palynology by Charles J. Felix (Reprint ed.). New York: John Wiley & Sons. LCCN 61006768. OCLC 12877482.

- Benton, Michael J. (1997). Vertebrate Palaeontology (2nd ed.). London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 978-0-412-73810-4. OCLC 37378512.

- Browne, Janet (2003) [Originally published 2002]. Charles Darwin: The Power of Place. Vol. 2. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 978-0-7126-6837-8. OCLC 806284755.

- Castro, Peter; Huber, Michael E. (2003). Marine Biology. Original art work by William Ober and Claire Garrison (4th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-029421-9. LCCN 2002190248. OCLC 49259996.

- Chapleau, François; Amaoka, Kunio (1998). "Flatfishes". In Paxton, John R.; Eschmeyer, William M. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Fishes. Illustrations by David Kirshner (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2. LCCN 98088228. OCLC 39641701.

- Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. LCCN 06017473. OCLC 741260650. The book is available from The Complete Work of Charles Darwin Online. Retrieved 2015-05-13.

- Donovan, Stephen K.; Paul, Christopher R. C., eds. (1998). The Adequacy of the Fossil Record. Chichester; New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-471-96988-4. LCCN 98010110. OCLC 38281286.

- Eldredge, Niles; Gould, Stephen Jay (1972). "Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism". In Schopf, Thomas J. M. (ed.). Models in Paleobiology. San Francisco, CA: Freeman, Cooper. ISBN 978-0-87735-325-6. LCCN 72078387. OCLC 572084.

- Freeman, Scott; Herron, Jon C. (2004). Evolutionary Analysis (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-101859-4. LCCN 2003054833. OCLC 52386174.

- Gingerich, Philip D.; Russell, Donald E. (1981). Pakicetus inachus, a New Archaeocete (Mammalia, Cetacea) From the Early-Middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan) (PDF) (Research report). Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology. Vol. 25. Ann Arbor, MI: Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan. pp. 235–246. ISSN 0097-3556. LCCN 82621252. OCLC 8263404.

- Gould, Stephen Jay (1980). The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-01380-1. LCCN 80015952. OCLC 6331415.

- Haeckel, Ernst (2011) [Originally published 1912; London: Watts & Co.]. The Evolution of Man. Vol. 1. Translated from the German by Joseph McCabe (5th enlarged ed.). Hamburg, Germany: Tredition Classics. ISBN 978-3-8424-6302-8. OCLC 830523724.

- Lamarck, Jean-Baptiste (1815–1822). Histoire naturelle des animaux sans vertèbres (in French). Paris: Verdière. LCCN 07018340. OCLC 5269931.

- Lovejoy, Arthur O. (1936). The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. William James Lectures, 1933. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. LCCN 36014264. OCLC 192226.

- Leche, V. (1904). "Archæopteryx". In Meijer, Bernhard (ed.). Nordisk familjebok (in Swedish) (New, revised and richly illustrated ed.). Stockholm: Nordisk familjeboks förlags aktiebolag. LCCN 15023737. OCLC 23562281.

- Prothero, Donald R. (2007). Evolution: What the Fossils Say and Why it Matters. Original illustrations by Carl Buell. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13962-5. LCCN 2007028804. OCLC 154711166.

- Reader, John (2011). Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins. Foreword by Andrew Hill (Enlarged and updated ed.). Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927685-1. LCCN 2011934689. OCLC 707267298.

- Shubin, Neil (2008). Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-375-42447-2. LCCN 2007024699. OCLC 144598195.

- Swisher, Carl C. III; Curtis, Garniss H.; Lewin, Roger (2001) [Originally published 2000]. Java Man: How Two Geologists Changed Our Understanding of Human Evolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-78734-3. LCCN 2001037337. OCLC 48066180.

- Wellnhofer, Peter (2004). "The Plumage of Archaeopteryx: Feathers of a Dinosaur?". In Currie, Philip J.; Koppelhus, Eva B.; Shugar, Martin A.; et al. (eds.). Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. Life of the Past. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34373-4. LCCN 2003019035. OCLC 52942941.

- Wellnhofer, Peter (2009). Archaeopteryx: The Icon of Evolution. Translated by Frank Haase; foreword by Luis M. Chiappe (Revised English edition of the 1st German ed.). München: Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil. ISBN 978-3-89937-108-6. OCLC 501736379.

External links

edit- Lloyd, Robin (11 February 2009). "Fossils Reveal Truth About Darwin's Theory". LiveScience. Ogden UT: Purch. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- Hunt, Kathleen (17 March 1997). "Transitional Vertebrate Fossils FAQ". TalkOrigins Archive. Houston, TX: The TalkOrigins Foundation, Inc. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Tiktaalik roseae". Chicago, IL: University of Chicago. Archived from the original on 12 November 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- "Whales Tohorā". Wellington, New Zealand: Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- Hutchinson, John R. (22 January 1998). "Are Birds Really Dinosaurs?". DinoBuzz. Berkeley, CA: University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 19 May 2015.