The Welles Declaration was a diplomatic statement issued on July 23, 1940, by Sumner Welles, the acting US Secretary of State, condemning the June 1940 occupation by the Soviet army of the three Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – and refusing to diplomatically recognize their subsequent annexation into the Soviet Union.[1] It was an application of the 1932 Stimson Doctrine of nonrecognition of international territorial changes that were executed by force[2] and was consistent with US President Franklin Roosevelt's attitude towards violent territorial expansion.[3]

The 1940 Soviet invasion was an implementation of its 1939 Nazi-Soviet Pact, which contained a secret protocol by which Nazi Germany and Stalinist USSR agreed to partition the independent nations between them. After the pact, the Soviets engaged in a series of ultimatums and actions ending in the annexation of the Baltic states during the summer of 1940. The area held little strategic importance to the United States, but several legations of the US State Department established had diplomatic relationships there. The United States and the United Kingdom anticipated future involvement in the war, but US non-interventionism and a foreseeable British–Soviet alliance deterred open confrontation over the Baltic states.

Welles, concerned with postwar border planning, had been authorized by Roosevelt to issue stronger public statements that gauged a move towards more intervention. Loy Henderson and other State Department officials familiar with the area kept the administration informed of developments there, and Henderson, Welles, and Roosevelt worked together to compose the declaration.

The declaration established a five-decade nonrecognition of the annexation.[4] The document had major significance for overall US policy toward Europe in the critical year of 1940.[5] The US did not engage the Soviet Union militarily in the region, but the declaration enabled the Baltic states to maintain independent diplomatic missions, and Executive Order 8484 protected Baltic financial assets. Its essence was supported by all subsequent US presidents and congressional resolutions.

The Baltic states re-established their independence in 1990 and 1991.

Background

edit19th and early 20th centuries

editFrom the late 18th into the early 20th century, the Russian Empire annexed the regions that are now the three Baltic states as well as Finland. Their national awareness movements began to gain strength, and they declared their independence in the wake of World War I. All of the states were recognized by the League of Nations during the early 1920s. The Estonian Age of Awakening, the Latvian National Awakening, and the Lithuanian National Revival expressed their wishes to create independent states. After the war, the three states declared their independence: Lithuania re-established its independence on February 16, 1918; Estonia on February 24, 1918; and Latvia on November 18, 1918. Although Baltic states often were seen as a unified group, they have dissimilar languages and histories.[6] Lithuania was recognized as a state in 1253, and Estonia and Latvia emerged from territories held by the Livonian Confederation (established 1243). All three states were admitted into the League of Nations in 1921.[6]

The U.S. had granted full de jure recognition to all three Baltic states by July 1922. The recognitions were granted during the shift from the Democratic administration of Woodrow Wilson to the Republican administration of Warren Harding.[4] The U.S. did not sponsor any meaningful political or economic initiatives in the region during the interwar period, and its administrations did not consider the states to be strategically important, but the country maintained normal diplomatic relations with all three.[7]

The U.S. had suffered over 100,000 deaths during the war[8] and pursued a non-interventionist policy since it was determined to avoid involvement in any further European conflicts.[7] In 1932, however, U.S. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson formally criticized the 1931 Japanese invasion of Manchuria, and the resulting Stimson Doctrine would go on to serve as a basis for the Welles declaration.[9]

Outbreak of World War II

editThe situation changed after the outbreak of World War II. Poland was invaded in September 1939. The United Kingdom became involved, and the series of German victories in Denmark, Norway, and the Netherlands during spring 1940 were alarming. Britain was clearly threatened, and its leadership discussed the possibility of an alliance with the Soviet Union.[10] Under the circumstances, direct British confrontation over the Baltic states was difficult.[10]

Roosevelt did not wish to lead the U.S. into the war, and his 1937 Quarantine Speech indirectly denouncing aggression by Italy and Japan had met mixed responses. Welles felt freer in that regard and looking towards postwar border issues and the establishment of an American-led international body that could intervene in such disputes.[11][page needed] Roosevelt saw Welles's stronger public statements as experiments that would test the public mood towards American foreign policy.[11][page needed]

The secret protocol contained in the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union had relegated Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania to the Soviet sphere of influence. In late 1939 and early 1940, the Soviet Union issued a series of ultimatums to the Baltic governments that eventually led to the illegal annexation of the states.[7] (At about the same time, the Soviet Union was exerting similar pressure on Finland.) About 30,000 Soviet troops entered the Baltic states during June 1940, followed by arrests of their leaders and citizens.[12]

Elections to "People's Assemblies" were held in all three states in mid-July; the Soviet-sponsored slates received between 92.2% and 99.2% of the vote.[13] In June, John Cooper Wiley of the State Department sent coded telegrams to Washington reporting developments in the Baltics, and the reports influenced Welles.[14] The U.S. responded with a July 15 amendment to Executive Order 8389 that froze the assets of the Baltic states, grouped them with German-occupied countries, and issued the condemnatory Welles Declaration.[4]

Formulation

editThe Welles Declaration was written by Loy W. Henderson in consultation with Welles and Roosevelt. Welles would go on to participate in the creation of the Atlantic Charter, which stated that territorial adjustments should be made in accordance with the wishes of the peoples concerned.[15] He increasingly served as acting Secretary of State during Cordell Hull's illnesses.[16] Henderson, the State Department's Director of the Office of European Affairs, was married to a Latvian woman.[17] He had opened an American Red Cross office in Kaunas, Lithuania, after World War I and served in the Eastern European Division of the State Department for 18 years.[18]

In a conversation on the morning of July 23, Welles asked Henderson to prepare a press release "expressing sympathy for the people of the Baltic States and condemnation of the Soviet action."[18][19] After reviewing the statement's initial draft, Welles emphatically expressed his opinion that it was not strong enough. In the presence of Henderson, Welles called Roosevelt and read the draft to him. Roosevelt and Welles agreed that it needed strengthening. Welles then reformulated several sentences and added others which apparently had been suggested by Roosevelt. According to Henderson, "President Roosevelt was indignant at the manner in which the Soviet Union annexed the Baltic States and personally approved the condemnatory statement issued by Under Secretary Welles on the subject."[18] The declaration was made public and telegraphed to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow later that day.[18][20]

Text

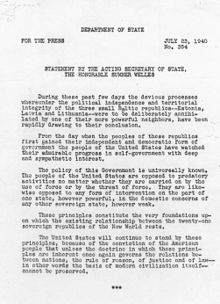

editThe statement read:[2]

During these past few days the devious processes whereunder the political independence and territorial integrity of the three small Baltic Republics – Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania – were to be deliberately annihilated by one of their more powerful neighbors, have been rapidly drawing to their conclusion.

From the day when the peoples of those Republics first gained their independent and democratic form of government the people of the United States have watched their admirable progress in self-government with deep and sympathetic interest.

The policy of this Government is universally known. The people of the United States are opposed to predatory activities no matter whether they are carried on by the use of force or by the threat of force. They are likewise opposed to any form of intervention on the part of one state, however powerful, in the domestic concerns of any other sovereign state, however weak.

These principles constitute the very foundations upon which the existing relationship between the twenty-one sovereign republics of the New World rests.

The United States will continue to stand by these principles, because of the conviction of the American people that unless the doctrine in which these principles are inherent once again governs the relations between nations, the rule of reason, of justice and of law – in other words, the basis of modern civilization itself – cannot be preserved.

Impact

editWorld War II

editWelles also announced that the US government would continue to recognize the foreign ministers of the Baltic countries as the envoys of sovereign governments.[21] Meanwhile, the Department of State instructed US representatives to withdraw from the Baltic states for "consultations".[21] In 1940, The New York Times described the declaration as "one of the most exceptional diplomatic documents issued by the Department of State in many years."[21]

The declaration was a source of contention during the subsequent alliance between the Americans, the British, and the Soviets, but Welles persistently defended it.[22] In a discussion with the media, he asserted that the Soviets had maneuvered to give "an odor of legality to acts of aggression for purposes of the record."[21][2] In a memorandum describing his conversations with British Ambassador Lord Halifax in 1942, Welles stated that he would have preferred to characterize the plebiscites supporting the annexations as "faked".[23] In April 1942 he wrote that the annexation was "not only indefensible from every moral standpoint, but likewise extraordinarily stupid." He interpreted any concession in the Baltic issue as a precedent that would lead to further border struggles in eastern Poland and elsewhere.[24]

As the war intensified, Roosevelt accepted the need for Soviet assistance and was reluctant to address postwar territorial conflicts.[25][26] During the 1943 Tehran Conference, he "jokingly" assured Stalin that when Soviet forces reoccupied Baltic countries, "he did not intend to go to war with the Soviet Union on this point." However, he explained, "the question of referendum and the right of self-determination" would constitute a matter of great importance for the Americans.[27] Despite his work with Soviet representatives in the early 1940s to forward the alliance, Welles saw Roosevelt's and Churchill's lack of commitment as dangerous.[26]

Postwar

editThe declaration linked American foreign policy towards the Baltic states with the Stimson Doctrine, which did not recognize the 1930s Japanese, German and Italian occupations.[28] It broke with Wilsonian policies, which had supported a strong Russian presence as a counterweight to German power.[12][1] During the Cold War, the Baltic issue was used as a point of leverage in American–Soviet relations.[1]

Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, a judge of international law, described the basis of the nonrecognition doctrine as being founded on the principles of ex injuria jus non oritur:

This construction of non-recognition is based on the view that acts contrary to international law are invalid and cannot become a source of legal rights for the wrongdoer. That view applies to international law one of "the general principles of law recognized by civilized nation." The principle ex injuria jus non oritur is one of the fundamental maxims of jurisprudence. An illegality cannot, as a rule, become a source of legal right to the wrongdoer.[29]

Like the Stimson Doctrine, Welles's declaration was largely symbolic in nature, but it offered some material benefits in conjunction with Executive Order 8484, which enabled the diplomatic representatives of the Baltic states in various other countries to fund their operations, and it protected the ownership of ships flying Baltic flags.[30] By establishing the policy, the executive order allowed some 120,000 postwar displaced persons from the Baltic states to avoid repatriation to the Soviet Union and to advocate independence from abroad.[31][32]

The American position that the Baltic states had been forcibly annexed would remain its official stance for 51 years. Subsequent presidents and congressional resolutions reaffirmed the substance of the declaration.[28] President Dwight Eisenhower asserted the right of the Baltic states to independence in an address to the U.S. Congress on January 6, 1957. After confirming the Helsinki Accords in July 1975, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution that it would not affect U.S. recognition of the sovereignty of Baltic states.[28]

On July 26, 1983, on the 61st anniversary of de jure recognition of the three Baltic countries by the U.S. in 1922, President Ronald Reagan re-declared the recognition of the independence of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. The declaration was read in the United Nations as well.[28] Throughout the 51 years that followed the 1940 occupation of the Baltic states, all U.S. official maps and publications that mentioned the Baltic states included a statement of U.S. non-recognition of Soviet occupation.[28]

The independence movements in the states in the 1980s and the 1990 succeeded, and the United Nations recognized all three in 1991.[33] They went on to become members of the European Union and NATO. Their development since independence is generally regarded as the most successful among post-Soviet states.[34] [35]

Commenting on the declaration's 70th anniversary, U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton described it as "a tribute to each of our countries' commitment to the ideals of freedom and democracy."[36] On July 23, 2010, a commemorative plaque inscribed with its text in English and Lithuanian was formally dedicated in Vilnius, the Lithuanian capital.[37]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Hiden, et al, p. 3

- ^ a b c Hiden, et al. p. 39

- ^ Hiden, et al, p. 40

- ^ a b c Made, Vahur. "Foreign policy statements of Estonian diplomatic missions during the Cold War: establishing the Estonian pro-US discourse". Estonian School of Diplomacy. Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ^ Hiden, et al, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b Ashbourne, p. 15

- ^ a b c Hiden, et al, p. 33

- ^ "American War and Military Operations Casualties: Lists and Statistics" (PDF). CSR Report for Congress. 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ^ Hiden, et al, p. 39

- ^ a b Gorodetsky, Gabriel (2002). Stafford Cripps' Mission to Moscow, 1940–42. Cambridge University Press. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-0-521-52220-5.

- ^ a b O'Sullivan, Christopher D. (2007). Sumner Welles, Postwar Planning, and the Quest for a New World Order, 1937–1943. Columbia University Press, reprinted by Gutenberg-e.org. ISBN 978-0-231-14258-8.

- ^ a b Lapinski, John Joseph (Fall 1990). "A Short History of Diplomatic Relations Between the United States and the Republic of Lithuania". Lituanus. 3 (36). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2009-05-14.

- ^ Misiunas, Romuald J.; Taagepera, Rein (1993). The Baltic States: Years of Dependence, 1940–1990. University of California Press. p. 28. ISBN 0-520-08228-1.

- ^ "Bearing Witness: The Story of John & Irena Wiley" (PDF). US Embassy in Estonia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- ^ Dallek, p. 283

- ^ Doenecke, Justus D.; Stoler, Mark A. (2005). Debating Franklin D. Roosevelt's Foreign Policies, 1933–1945. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 12. ISBN 0-8476-9416-X.

- ^ "How Loy Henderson Earned Estonia's Cross of Liberty" (PDF). U.S. Embassy in Estonia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-27. Retrieved 2009-10-16.

- ^ a b c d "Oral History Interview with Loy W. Henderson". The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. 1973. Retrieved 2009-05-02.

- ^ Hiden, et al., pp. 39–40

- ^ Hiden, et al., p. 41

- ^ a b c d Hulen, Bertram (1940-07-24). "U.S. Lashes Soviet for Baltic Seizure". The New York Times. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ^ Dunn, p. 118

- ^ Bennett, Edward Moore (1990). Franklin D. Roosevelt and the search for victory. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 0-8420-2365-8.

- ^ Dunn, p. 161

- ^ Hiden, et al., pp. 41–42

- ^ a b Welles, Benjamin (1997). Sumner Welles: FDR's global strategist: a biography. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-312-17440-8.

- ^ Dallek, p. 436

- ^ a b c d e Miljan, p. 346.

- ^ Krivickas, Domas (Summer 1989). "The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of 1939: Legal and Political consequences". Lituanus. 2 (34). ISSN 0024-5089. Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2009-05-04.

- ^ Hiden, et al., p. 42

- ^ Hiden, et al., p. 43

- ^ "Esten, letten und litauer in der britischen besatzungszone deutschlands. Aus akten des Foreign office = Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians in the British occupation zone of Germany". Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas. 53 (1). 2005. ISSN 0021-4019. Archived from the original on 2012-07-26. Retrieved 2009-10-19.

- ^ Europa Publications Limited (1999). Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Vol. 4. Routledge. p. 332. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- ^ O'Connor, Kevin (2003). The History of the Baltic States. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 196. ISBN 0-313-32355-0.

- ^ Serhii, Plokhy (November 30, 2021). "The Return of History: The Post-Soviet Space Thirty Years after the Fall of the USSR". Ukrainian Research Institute of Harvard University.

- ^ Clinton, Hillary Rodham (2010-07-22). "Seventieth Anniversary of the Welles Declaration". U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 2010-07-30. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

- ^ Ketlerius, Artūras (2010-07-23). "Aneksijos nepripažinimo minėjime – padėkos Amerikai ir kirčiai Rusijai". Delfi.lt. Retrieved 2010-07-23.

Sources

edit- Alexandra Ashbourne. Lithuania: The Rebirth of a Nation, 1991–1994. Lexington Books, 1999. ISBN 978-0-7391-0027-1.

- Edward Moore Bennett. Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Search for Victory: American–Soviet Relations, 1939–1945. Rowman & Littlefield, 1990. ISBN 978-0-8420-2365-8.

- Robert Dallek. Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Foreign Policy, 1932–1945: With a New Afterword. Oxford University Press US, 1995. ISBN 978-0-19-509732-0.

- Dennis J. Dunn. Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. University Press of Kentucky, 1998. ISBN 978-0-8131-2023-2.

- John Hiden, Vahur Made, David J. Smith, editors. The Baltic Question During the Cold War. London: Routledge, 2008. ISBN 978-0-415-37100-1.

- Toivo Miljan. Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Volume 43 of European historical dictionaries. Scarecrow Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8108-4904-4.