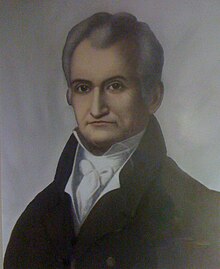

Colonel William Polk (9 July 1758 – 14 January 1834) was a North Carolina banker, educational administrator, political leader, renowned Continental officer in the War for American Independence, and survivor of the 1777/1778 encampment at Valley Forge.

Colonel William Polk | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of North Carolina Council of State[1] | |

| In office 1806–1807 Serving with Robert Burton, Nathaniel Jones, William Boylan, Bryan Whitfield, Reuben Wood, Lawrence Smith | |

| Appointed by | North Carolina House of Commons |

| Governor | Nathaniel Alexander |

| Supervisor of Internal Revenue for the District of North Carolina | |

| In office 1791–1808 | |

| Appointed by | George Washington |

| Member of the North Carolina House of Commons | |

| In office 1785–1786 Serving with Elijah Robertson | |

| Governor | Alexander Martin then Richard Caswell |

| Preceded by | Ephraim McLean |

| Succeeded by | Robert Ewing/Robert Hayes |

| Constituency | Davidson County (now part of Tennessee) |

| Member of the North Carolina House of Commons | |

| In office 1787–1788 Serving with Caleb Phifer | |

| Governor | Samuel Johnston |

| Preceded by | George Alexander |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Douglass |

| Constituency | Mecklenburg County, North Carolina |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 9 July 1758 Mecklenburg County, North Carolina |

| Died | 14 January 1834 (aged 75) Raleigh, North Carolina |

| Resting place | City Cemetery, Raleigh, North Carolina Section E-3 35°46′41″N 78°37′57″W / 35.77802°N 78.63237°W |

| Political party | Federalist |

| Spouse(s) | Griselda Glichrist(1789-1799), Sarah Hawkins (1801-1843) |

| Relations | James K. Polk (first cousin, once removed), Ezekiel Polk (nephew of), Leonidas Polk (father of) |

| Alma mater | Queen's College(not Queens University of Charlotte) |

| Occupation | Soldier, Surveyor, Land Speculator, Banker, Politician, Educator |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | South Carolina and North Carolina militia, Continental Army |

| Years of service | 1775-1781 |

| Rank | Major, later Lieutenant-Colonel |

| Unit | 9th North Carolina Regiment, Mecklenburg County Regiment[10] |

| Commands | Polk's Regiment of Light Dragoons[10] |

| Battles/wars | Canebrake, Brandywine, Germantown, Camden, Cowan's Ford, Guilford Court House, and Eutaw Springs |

| Survivor of | The 1777/1788 Encampment at Valley Forge |

| [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] | |

Early life and background

editWilliam Polk was born in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, on July 9, 1758, the eldest child of Thomas Polk and his wife Sussana Spratt. From the earliest days of rebellion against British authority, Mecklenburg had been a hotbed of revolutionary fervor, and the Polk family was very active in this cause. William's father was commander of the local militia, a rumored key player in adoption of the Mecklenburg Resolves of May 31, 1775, and later colonel of the 4th North Carolina Regiment, Continental Line.

Following their father's example, three of Thomas Polk's sons served as officers in the war against the British. The younger Thomas was killed in action serving alongside his brother William at the Battle of Eutaw Springs.[11][12]

American Revolutionary War

edit- At the onset of military action between the American colonies and Great Britain, William Polk left Queens College (an unrelated precursor of the modern Queens University) to accept a commission as second lieutenant in his uncle Ezekiel Polk's company of the Third South Carolina Regiment, commanded by Col. William Thomson. In a campaign to subdue Tory forces in South Carolina, he was severely wounded in the left shoulder at Great Cane Brake on 23 December 1775. Borne on a litter 120 miles to his father's home in North Carolina, he spent the following nine months recuperating from the dangerously infected wound. His reportedly was the first American blood shed south of Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts.[13]

- 1776, November 26: The Provincial Congress of North Carolina at Halifax elected young Polk major of the 9th North Carolina Regiment, North Carolina Continental Line.[5] When the North Carolina regiments were ordered north, the Ninth had only about half its complement of men, and its colonel and lieutenant colonel remained in North Carolina to superintend further recruiting. Polk, a combat veteran of imposing stature—he stood six feet, four [14]—was given command and marched the regiment to Maryland for inoculation against smallpox, then to Trenton, N.J., where it joined the main body of General Washington's army.[15]

- 1777, September 11: Polk and his regiment saw action at the Battle of Brandywine.[16]

- 1777, October 4: At the Battle of Germantown Polk was shot in the mouth while in the act of giving a command. The musket ball ranged along the upper jaw, knocking out four teeth and shattering the jawbone.[15]

- 1777/1778, winter: Recuperating from this wound, Polk remained with his regiment during the difficult encampment at Valley Forge.

- 1778, March: Their ranks severely depleted by death and the expiration of enlistments, North Carolina's ten regiments were reduced to four. Superfluous officers, including Polk, were removed by lot from active service. Polk returned to North Carolina, where he engaged in recruiting duty.[2]

- 1778, fall – 1780, April: Polk continued in his recruiting duties and participated in skirmishes against the Tories.

- 1780, May: After the fall of Charleston, the Southern Department of the army was reorganized under General Horatio Gates. Polk was assigned as an aide to Major General Richard Caswell at the Battle of Camden,[5][10] the former governor of North Carolina.

- 1780: Polk saw action at the disastrous Battle of Camden.[17] When the Continentals began to give ground, Polk joined with the North Carolina militia and fought with them. Once De Kalb fell and the rout of Continentals was complete, Polk was able to lead a large number of troops in a successful retreat to North Carolina. That fall he acquired a position under General William Davidson.[18]

- 1781, January: General Davidson's militia, including Polk, marched to the aid of Daniel Morgan, who after his success at Cowpens was on the run from the main body of Cornwallis's army.

- 1781, February - April: When Cornwallis attempted to cross the Catawba at Cowan's Ford, he was attacked by Davidson's militia. Polk was riding alongside Davidson when the general was shot from his horse and killed instantly.[19] Word of Davidson's death spread quickly, and the demoralized militia broke in the face of an enemy bayonet charge. Polk rallied the few men he could and led them to Salem, reporting for service to General Andrew Pickens, with whom he remained until, following the Battle of Guilford Court House, Pickens left the army of General Nathanael Greene. Soon thereafter Polk was commissioned lieutenant colonel by Governor John Rutledge of South Carolina and took command of the 4th and then the 3rd regiments of that state, mustering his regiment under the command of General Thomas Sumter. Less than a month after being commissioned, Polk, together with troops under Colonel Wade Hampton, grandfather of the Confederate general of that name, led his regiment on a forced march of sixty miles in seventeen hours, surprising the British at Friday's Ferry on the Congaree and burning the blockhouse near Fort Granby, South Carolina.[20]

- 1781, May 11–15: Polk joined General Greene at Fort Motte, which capitulated on the second day of a siege, and then marched under General Sumter's command to Orangeburg, where the British garrison quickly surrendered.[20]

- 1781, July. Polk's regiment invested the British garrison around Watboo Church, burning bridges and causeways, then retired to await the arrival of Sumter's artillery. In the morning the British cavalry made "a furious charge," but were thrown back. That night the British abandoned their position, burned the church and other buildings and retreated to Quinby Bridge, where they were saved from certain defeat by Sumter's failure to employ his artillery.[21]

- 1781, September 8: Polk's regiment covered the left wing of the American army under General Nathanael Greene at the Battle of Eutaw Springs. While charging the enemy, Polk's horse was shot dead and fell on top of him, pinning him to the ground. A British soldier was in the act of plunging a bayonet into Polk when he was cut down by a sergeant in Polk's regiment.[22] (Polk's brother Lieutenant Thomas Polk was killed during the battle.) With regard to Colonel Polk's performance that day, Greene wrote in his official report:

Lieutenant-Colonels Polk and Middleton were no less conspicuous for their good conduct than their intrepidity, and the troops under their command gave a specimen of what may be expected from men naturally brave when improved by proper discipline.[23]

- Eutaw Springs was the last major battle in the South prior to Yorktown and was Polk's final military engagement.[24] With the end of hostilities, Polk returned to North Carolina, a veteran of some of the Revolution's fiercest battles and a survivor of the harshest winter encampment in the history of the United States military. He was twenty-two years old.

Post-war years

editPolitician and public servant

editIn 1783 the North Carolina General Assembly appointed Polk as Surveyor General of the Middle District, now a part of Tennessee. In this capacity Polk also acquired large tracts of land in the area. Twice he was elected to the House of Commons before returning in 1786 to his native Mecklenburg County.[2][5][7][25] He was re-elected to the House of Commons in 1787, served a one-year term and was re-elected in 1790.[8] He was a candidate for Speaker of the House in 1791, but was defeated by Stephen Cabarrus.[26] That March President George Washington appointed him as Supervisor of Internal Revenue for the District of North Carolina, a position he held for seventeen years, or until the Internal Revenue Laws were repealed.[26][27]

Polk was among the Continental Army officers who founded the North Carolina Society of the Cincinnati on October 23, 1783.[28]

After the death of his first wife in 1799, Polk moved to property on Blount Street in Raleigh.[2][29] In December of that year he was elected Grand Master of Masons of North Carolina and served in that office until December 1802.[30][2]

Federalists in the state legislature nominated him for governor in 1802, but by a two-to-one margin he lost to John Baptista Ashe, a fellow officer in the Revolution.[2] Ashe died before taking office.[31]

Polk was appointed as the first president of the State Bank of North Carolina in 1811 and held that office for eight years.[2][5]

In March 1812, as war with Britain seemed imminent, President Madison offered Polk a commission as brigadier in the U.S. Army. A Federalist and opponent of the war, he declined the offer.[2][5][27] Not until August 1814, when the British sacked Washington, did he change his opposition to the war. Writing his brother-in-law William Hawkins, governor of North Carolina, he offered his services to the state in whatever capacity the governor saw fit. Inasmuch as North Carolina was not seriously threatened, he was not called upon.[32]

In June 1818 Polk became one of the first vice presidents of Raleigh Auxiliary of the American Colonization Society,[33] which sought to resettle free American blacks in a colony in West Africa. This colony developed as Liberia. Polk remained active in the group for many years.[2]

The Federalists nominated him as candidate for governor in 1814, and again he was defeated.[2]

Canova's Washington

editAfter the War of 1812, the North Carolina legislature commissioned the celebrated sculptor Antonio Canova of Venice, Italy, to produce a statue of George Washington for the State House. On Christmas Eve 1821 it arrived in Raleigh and was met with great fanfare, including a 24-gun salute, marching bands, and a parade of both houses of the legislature and the governor. In last position, just ahead of the statue, were veterans of the Revolution, with Polk bearing the Stars and Stripes. Polk also gave a speech that day.[34] The old State House building burned in June 1831 and the statue was destroyed.[35] An accurate copy of the statue was produced in Italy from preserved molds in the 21st century and installed in the rotunda of the new Capitol building.

| Speech Given by Colonel William Polk at the Dedication of Canova's Washington State House in Raleigh, North Carolina. December 24, 1821 |

|---|

| Fellow Citizens:- An enlightened Legislature, faithful to the emotions of a grateful people, has procured the Statue of our beloved Washington, formed by the highest skill of and artist whom all agree in calling the Michael Angelo of the Age.

Rome- once the citadel of the earth, the terror of Kings; now fallen, now defaced- still nourishes for the arts those talents by which patriotism and republican virtue are honored and recorded in the New World. Thus, it is that Providence, in its wise and mysterious dispensations, makes even degenerate nations in the instruments of preserving that holy reverence for the rights of humanity, which must ultimately issue in the establishment of the liberties of the world. The country of Phocion and Leonidas may again be free; and some future Phidias, catching inspiration from the sublime ruins around him, make the marble tell to posterity the heroic actions of his contemporaries. America may justly glory in her Washington, the founder of her liberty, the friend of man. History and tradition are explored in vain for a parallel to his character. In other illustrious men, each possessed some shining quality, that was the foundation of his fame; in Washington, all the virtues were united- force of body, vigor of mind, ardent patriotism, contempt for riches, gentleness of disposition, courage and conduct in war. In the annals of modern greatness he stands alone, and noblest names of antiquity lose their luster in his presence. Born the benefactor of mankind, he united all the qualities necessary to an illustrious career. Nature made him great; he made himself virtuous. Called by his country to the defense of her liberties, the triumphantly vindicated the rights of man, and laid in the principles of freedom the foundations of a great republic. Twice invested with the supreme magistracy by the unanimous voice of the free people, he surpassed in the cabinet the glories of the field; and, voluntarily resigning the scepter of the sword, retired to the private shades of life. A spectacle so new, so sublime, was contemplated with the profoundest admiration; and the name of Washington, adding new luster to humanity, resounded to the remotest regions of the earth. Magnanimous in youth, glorious through life, great in death, his highest ambition the happiness of mankind, his noblest victory the conquest of himself, bequeathing to posterity the inheritance of his fame, and building his monument in the hearts of his countrymen, he lived the ornament of the eighteenth century- he dies, regretted by a mourning world. The record of such virtues should be transmitted to posterity by every means the Muse of History, of Painting, and of Sculpture, can employ; and who is not profound of his country when he sees her thus munificently, consecrating the memory of the first patriots? It is gratifying to know that the task was a favorite one to the Artist; he had an exalted admiration of the character of Washington, and he has accordingly lavished on the work some of the richest treasures of his genius. But Canova is an enlightened friend of liberty, and worthy to be the sculptor of its author. May we not, then, fellow-citizens, indulge the hope that this beautiful specimen of the arts, besides its moral effects in holding up to the imitation of youth the greatest qualities it commutates, also refine their taste and awaken their latent energies of genius- that while it inculcates the virtues that render life unusual to our country, it may diffuse a relish for the arts that embellish society, and call forth a display of the varied powers of man's ingenuity.

|

Lafayette's visit to Raleigh

editLafayette visited Raleigh in March 1825 as part of his Grand Tour of the United States.[36] Colonel Polk was appointed to give an address on the occasion.[27] After his speech, Polk and Lafayette embraced and wept in memory of what they had shared during the Revolution.[37] Lafayette attended various balls, dinners, and other events, including breakfast at Colonel Polk's home on the morning of March 3.[37]

| Speech Given by Colonel William Polk welcoming General Lafayette upon this arrival in Raleigh, North Carolina. March 2, 1825 |

|---|

| General Lafayette: Charged by my fellow citizens with the grateful duty of offering you cordial welcoming to the capital of their state; I know that I express the universal sentiment, in adding, that your arrival in the bosom of our country is one of the most acceptable events that could have occurred in our day and generation. Deeply sensible as they are of the inestimable blessings they enjoy under a free Constitution, they would not yet be unworthy of them, they did not frequently refer(illegible) to the circumstances under which their foundation was laid – to the vicissitudes of toil, privation, and suffering, through which they were gained- and, above all cherish a lively feeling of gratitude towards those, whose patriotic spirit and heroic daring put every thing [sic] to risque [sic], but honor, to build up the heritage of freedom for their posterity. It is impossible to review the history of these times, and not dwell with delight on the name and services of Lafayette, who, animated with the purest love of liberty, relinquished what ordinary minds esteem the choicest blessings of life, to aid in its defence [sic]-quitting family, friends, fortune & country, to encounter the perils of a military life, in an unequal and almost hopeless contest and who, in the darkest period of the Revolution, instead of being applied at the extent of danger, derived new and or from the gathering storm. We can never forget General, how much we owe to your skill and gallantry in the field, to the strength your countenance and example inspired to our just but desponding cause – the successful issue of your generous efforts to procure for it, the aid of your brave and high-minded countrymen, and the emotions of joy you expressed, when you communicated to the army, the first intelligence, that your sovereign had become the ally of these infant States. The enviable lot of mortality, has left but few of your brave companions in arms in this State, and from them, time has ravaged most of the strength, that war and wounds had left. Yet they have come from their distant homes to participate in the general joy of your arrival, and once more, to gladden their sight with the view of their beloved leader. That aged and honored group; whose furrowed cheeks are bedewed with the tears of mingled joy and gratitude, and, whom you see drawn, by a reverential sympathy towards the sculptured resemblance, of the Father of this Country, are impatient to clasp you to their hearts, to recall themselves to your remembrance, & to forget for a moment, the infirmities of age in retracing those well fought fields, where their youthful blood flowed freely with your own, to cement the foundations of this republic. To those who did not witness, history has presented a faithful record of your disintereste [sic] and persevering services in our cause; and all have felt a correspondent interest in your life and fortunes, amidst the great events which have agitated Europe, since your return thither. They have mourned over your personal sufferings, but they have been consoled, by the reflection, that no adverse fortune, could make you cease to be the steady and incorruptible friend of Rational Liberty, and the empire of laws; and by the certainty, that the same just views of human society and strong benevolence of heart, that governed your honorable career in America, would preside over it, in Europe; and enshrine you in the affections of all the enlightened friends of man. The excellence of the government you assisted in establishing, would be manifest to all nations could they witness its practicable operation in securing the happiness and elevating the character of its citizens, in giving a useful direction to their physical powers, and developing their moral energies. It is our warmest and cordial wish that your visit to a people, whom you have so greatly benefited, may be attended with every circumstance, that can render it happy, and that the evening of your days, may be solaced by the consciousness, that a virtuous life, and generous devotion to their cause, has secured you the gratitude of ten millions of freemen.

|

Service to education

editPolk was appointed as a trustee of the University of North Carolina in 1790 and served until his death, including a term as president of the trustees from 1802-1805.[2] Among other educational efforts, he founded a school for sixteen pupils in Raleigh in 1827 and assisted his wife Sarah in founding a school for poor children in 1822.[39]

Marriages and family

editIn October 1789 Polk married Grizelda Gilchrist,[27] a granddaughter of a former colonial attorney general of North Carolina.[2] She was born in Suffolk, Virginia, on October 24, 1768.[28] The couple had two children, Thomas Gilchrist Polk, born February 22, 1791, and William Julius Polk, born March 21, 1793.[40] Grizelda Polk died in 1799.[2]

On New Year's Day 1801, Polk married Sarah Hawkins.[2] Her brother William later was elected governor of North Carolina.[27] Sarah bore thirteen children, two of whom died in infancy.[40]

Notable relations

edit- Thomas Polk, William's father. Continental Army General and member of the Congress of the Confederation. Considered the "Father of Charlotte (North Carolina)" by some.

- Ezekiel Polk, his paternal uncle and first commanding officer during the Revolution.[41]

- James K. Polk, 11th President of the United States; William's first cousin, once removed, being the grandson of his father's brother Ezekiel.[42]

- Leonidas Polk, William's second son by his wife Sarah, was known as "The Fighting Bishop." An Episcopal bishop, he was commissioned as a Confederate general during the Civil War. (Killed in action at Pine Mountain, Tennessee.)[27] He was instrumental in establishing the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee. Until 2023, Fort Johnson was named Fort Polk in his honor.[43][44]

- Leonidas Lafayette Polk, great-great-grandson of William Polk, a Confederate colonel and first North Carolina Commissioner of Agriculture.[45]

- William Polk Hardeman Confederate Army General

- George Polk Journalist murdered in 1948.

Death

editPolk died on January 14, 1834, at his home in Raleigh.[46][47]

His obituary in the January 21, 1834, issue of the Raleigh Register contained the following:

Colonel Polk was at his death the sole surviving field officer of the North Carolina Line; and it will be no disparagement to the illustrious dead to say that no one of his compatriots manifested deeper or more ardent devotion to the cause of his country; that in her service no officer more gallantly exposed his life or more cheerfully endured privation and suffering, and that no one of his rank in the army contributed more by his personal services to bring that glorious contest to a successful end.

— The Raleigh Register, January 21, 1834, quoted by Marshall DeLancey Haywood[32]

Legacy

edit- The town of Polkville, North Carolina is named for him.[32]

- Polk County was named for him as he had property there.[32]

- Camp Polk, a World War I U.S. Army tank base in Raleigh, was named for him.[48]

- The original Polk Prison was built in 1920 on the grounds of Camp Polk. The prison facility is named for Colonel William Polk.[48] The North Carolina Museum of Art and its Museum Park now occupy the original site on Blue Ridge Road in Raleigh.[49]

- Polk Correctional Institution (originally Polk Youth Institution), opened in 1997 near Butner, North Carolina, is a North Carolina maximum-security prison for men aged 19–25.[48]

David Swain, the governor of North Carolina at the time of Polk's death, said:

He was a contemporary and personal friend of Andrew Jackson, not less heroic in war, and quite as sagacious, and more successful in private life. It is known that Colonel Polk greatly advanced the interests and enhanced the wealth of the hero of New Orleans by information furnished him from his field notes as a surveyor, and in directing Jackson in his selection of valuable tracts of land in the State of Tennessee; that to Samuel Polk, the father of the President (James K. Polk), he gave the agency of renting and selling his (William's) immense and valuable estate in lands in the most fertile section of that state; that as President of the Bank of North Carolina, he made Jacob Johnson, the father of President Andrew Johnson, its first porter; so that of the three native North Carolinians who entered the White House through the gates of Tennessee, all were indebted alike for the benefactions, and for promotion to a more favorable position in life, to the same individual, Colonel William Polk.

— David Swain, quoted by William H. Polk.[50]

Notes

edit- ^ The Council of State at this time was an official advisory panel for the Governor, the members of which were appointed by the legislature. The name, and some of the authority, of the Council was later transferred to the body of the state's elected executive officials.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McFarland 1979, p. 114

- ^ Angellotti 1923, p. 4

- ^ Angellotti 1923, p. 14

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson 1888, p. 56

- ^ Connor 1913, p. 428

- ^ a b Connor 1913, p. 586

- ^ a b Connor 1913, p. 697

- ^ Connor 1913, p. 776

- ^ a b c Lewis, J.D. "William Polk". North Carolina in the American Revolution. Retrieved March 31, 2019.

- ^ William S. Powell, North Carolina Through Four Centuries, University of North Carolina Press, 1989, pp. 176, 177.

- ^ William M. Polk, Leonidas Polk, Bishop and General, Longmans, Green & Co., 1915, p. 14.

- ^ "Autobiography of Colonel William Polk" in The Papers of Archibald D. Murphy, William Henry Hoyt, editor, North Carolina Historical Commission, Raleigh, 1914.

- ^ Mary Jones Polk Branch, Memoirs of a Southern Woman, Branch Publishing, Chicago, 1912, p. 83.

- ^ a b "Autobiography".

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 223

- ^ "Autobiography", p. 404-405.

- ^ Pension application of William Polk, S3706 fn51NC, Wake County, N.C., Superior Court of Law, spring term 1833.

- ^ John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse, John Wiley & Sons, 1997, p. 347.

- ^ a b "Autobiography", p. 407.

- ^ "Autobiography", p. 408.

- ^ "Autobiography"

- ^ William M. Polk, Leonidas Polk, Bishop and General, Longmans Green & Co., New York, 1915.

- ^ Mark M. Boatner, III, Encyclopedia of the American Revolution, Stackpole Books, 1994.

- ^ Polk 1912, p. 140

- ^ a b Haywood 1905, p. 366

- ^ a b c d e f Polk 1912, p. 141

- ^ a b Haywood 1905, p. 365

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 122

- ^ grandlodge 1998, p. 1

- ^ Congressional Biography of John Baptista Ashe 2000, p. 1

- ^ a b c d Haywood 1905, p. 367

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 165

- ^ a b Haywood, South Atlantic Quarterly 1902, p. 281

- ^ Haywood, South Atlantic Quarterly 1902, p. 285

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 222

- ^ a b Murray 1983, p. 225

- ^ Raleigh Register 1825, p. 1

- ^ Murray 1983, p. 188

- ^ a b Angellotti 1923, p. 16

- ^ Angellotti 1923, p. 8

- ^ Angellotti 1923, p. 22

- ^ Fort Polk Public Affairs Office 2010, p. 1

- ^ Thayer, Rose (June 13, 2023). "Fort Polk renamed Fort Johnson in honor of Black WWI hero". Stars and Stripes. Retrieved February 18, 2024.

- ^ Angellotti 1923, p. 30

- ^ Polk 1912, p. 144

- ^ Wilson 1888, p. 57

- ^ a b c Department of Correction 2011, p. 1

- ^ "North Carolina Museum of Art Expansion" (PDF). Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ Polk 1912, p. 143

References

edit- "About Fort Polk". Vernon Parish, Louisiana: US Army, Fort Polk Public Affairs Office. 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- "About Polk Correctional Institution". North Carolina Department of Correction. 2011. Retrieved March 4, 2011.

- Angellotti, Frank M. (1923). The Polks of North Carolina and Tennessee. Greenville, South Carolina: Southern Historical Press.

- "ASHE, John Baptista - Biographical Information". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Washington, DC: United States Congress. 2000. Retrieved 2011-02-28.

- Charlotte-Mecklenburg Library (2004). "Celebrating the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence: All About the Declaration, Signers Biographies: Thomas Polk". The Charlotte - Mecklenburg Story. Charlotte, North Carolina: Public Library of Charlotte & Mecklenburg County. Retrieved 2011-02-15.

- Connor, Robert, ed. (1913). A Manual of North Carolina [Issued by the North Carolina Historical Commission for the Use of Members of the General Assembly Session 1913] (HTML). University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill digitization project, Documenting the American South (1 ed.). Raleigh, North Carolina: E. M. Uzzell & Co. State Printers.

- Grand Lodge AF&AM of North Carolina (1998). "Officers of the Grand Lodge, A.F. & A.M. of North Carolina, the first 100 years". Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: Grand Lodge of North Carolina. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

- Haywood, Marshall DeLancey (1905). "William Polk". In Ashe, Samuel A. (ed.). Biographical History of North Carolina [From Colonial Times to the Present]. Vol. 2. Greensboro, North Carolina: Charles L. Van Noppen.

- Haywood, Marshall DeLancey (July 1902). "Canova's Statue of Washington". In Bassett, John Spencer (ed.). The South Atlantic Quarterly (Google eBook). Vol. 1. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University.

- McFarland, Daniel M. (1979). Powell, William S. (ed.). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography (Google eBook). Vol. 5 (P-S) (1 ed.). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2100-4. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- Murray, Elizabeth Reid (1983). Wake [Capital County of North Carolina]. Vol. 1: Prehistory through Centennial. Raleigh, North Carolina: Capital County Publishing Company. ASIN B000M0ZYF4.

- Polk, William H. (1912). Polk Family and Kinsmen. Louisville, Kentucky: Bradley and Gilbert. OL 7118519M.

- "General Lafayette". The Raleigh Register. Raleigh, North Carolina. 8 March 1825. (Microfilm of original newspaper provided by The Olivia Raney Local History Library, Wake County Public Libraries, Raleigh North Carolina.)

- Wilson, James Grant, ed. (1888). Appleton's Cyclopædia of American biography (Google eBook). Vol. 5: Pickering-Sumter. John Fiske. New York, New York: D. Appleton and Company. Bibcode:1887acab.book.....W. Retrieved 2011-02-13.

- "Past Masters of Phalanx Lodge No. 31 AF&AM Charlotte". Charlotte, North Carolina: Phalanx Lodge No. 31. 12 April 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.