A cotton gin—meaning "cotton engine"[1][2]—is a machine that quickly and easily separates cotton fibers from their seeds, enabling much greater productivity than manual cotton separation.[3] The separated seeds may be used to grow more cotton or to produce cottonseed oil.

Handheld roller gins had been used in the Indian subcontinent since at earliest AD 500 and then in other regions.[4] The Indian worm-gear roller gin was invented sometime around the 16th century[5] and has, according to Lakwete, remained virtually unchanged up to the present time. A modern mechanical cotton gin was created by American inventor Eli Whitney in 1793 and patented in 1794.

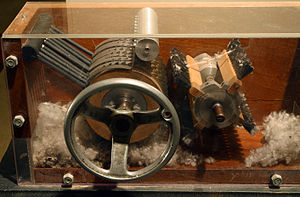

Whitney's gin used a combination of a wire screen and small wire hooks to pull the cotton through, while brushes continuously removed the loose cotton lint to prevent jams. It revolutionized the cotton industry in the United States, but also inadvertently led to the growth of slavery in the American South. Whitney's gin made cotton farming more profitable[citation needed] and efficient so plantation owners expanded their plantations and used more of their slaves to pick cotton. Whitney never invented the machine to harvest cotton: it still had to be picked by hand. The invention has thus been identified as an inadvertent contributing factor to the outbreak of the American Civil War.[6] Modern automated cotton gins use multiple powered cleaning cylinders and saws, and offer far higher productivity than their hand-powered precursors.[7]

Purpose

editCotton fibers are produced in the seed pods ("bolls") of the cotton plant where the fibers ("lint") in the bolls are tightly interwoven with seeds. To make the fibers usable, the seeds and fibers must first be separated, a task which had been previously performed manually, with production of cotton requiring hours of labor for the separation. Many simple seed-removing devices had been invented, but until the innovation of the cotton gin, most required significant operator attention and worked only on a small scale.[9]

Mechanism

editThis section needs expansion with: details about other kinds of gins; Whitney's is not the only kind. You can help by adding to it. (February 2023) |

Whitney's gin is made with two rotating cylinders. The first cylinder has lines of teeth around the circumference, and angled against this cylinder is a metal plate with small holes, "ginning ribs", through which the teeth can fit with minimal gaps. The teeth grip the cotton fibers as the mechanism rotates, dragging them through these small holes. The seeds are too big to fit through the holes, and are thus removed from the rotating cotton by the metal plate, before they fall into a collecting pot. On the other side of the first cylinder, there is a second cylinder, also rotating, with brushes attached. This second cylinder wipes the cotton from the first, and deposits it into the collecting bucket.

The seed is reused for planting or is sent to an oil mill to be further processed into cottonseed oil and cottonseed meal. The lint cleaners again use saws and grid bars, this time to separate immature seeds and any remaining foreign matter from the fibers. The bale press then compresses the cotton into bales for storage and shipping. Modern gins can process up to 15 tonnes (33,000 lb) of cotton per hour.

History

editA single-roller cotton gin came into use in India by the 5th century. An improvement invented in India was the two-roller gin, known as the "churka", "charki", or "wooden-worm-worked roller".[10]

Early cotton gins

editThe earliest versions of the cotton gin consisted of a single roller made of iron or wood and a flat piece of stone or wood. The earliest evidence of the cotton gin is found in the fifth century, in the form of Buddhist paintings depicting a single-roller gin in the Ajanta Caves in western India.[4] These early gins were difficult to use and required a great deal of skill. A narrow single roller was necessary to expel the seeds from the cotton without crushing the seeds. The design was similar to that of a mealing stone, which was used to grind grain. The early history of the cotton gin is ambiguous, because archeologists likely mistook the cotton gin's parts for other tools.[4]

Medieval and Early Modern India

editBetween the 12th and 14th centuries, dual-roller gins appeared in India and China. The Indian version of the dual-roller gin was prevalent throughout the Mediterranean cotton trade by the 16th century. This mechanical device was, in some areas, driven by waterpower.[11]

The worm gear roller gin, which was invented in the Indian subcontinent during the early Delhi Sultanate era of the 13th to 14th centuries, came into use in the Mughal Empire sometime around the 16th century,[12] and is still used in the Indian subcontinent through to the present day.[4] Another innovation, the incorporation of the crank handle in the cotton gin, first appeared sometime during the late Delhi Sultanate or the early Mughal Empire.[13] The incorporation of the worm gear and crank handle into the roller cotton gin led to greatly expanded Indian cotton textile production during the Mughal era.[14]

It was reported that, with an Indian cotton gin, which is half machine and half tool, one man and one woman could clean 28 pounds of cotton per day. With a modified Forbes version, one man and a boy could produce 250 pounds per day. If oxen were used to power 16 of these machines, and a few people's labor was used to feed them, they could produce as much work as 750 people did formerly.[15]

United States

editThe Indian roller cotton gin, known as the churka or charkha, was introduced to the United States in the mid-18th century, when it was adopted in the southern United States. The device was adopted for cleaning long-staple cotton but was not suitable for the short-staple cotton that was more common in certain states such as Georgia. Several modifications were made to the Indian roller gin by Mr. Krebs in 1772 and Joseph Eve in 1788, but their uses remained limited to the long-staple variety, up until Eli Whitney's development of a short-staple cotton gin in 1793.[17]

Eli Whitney's patent

editEli Whitney (1765–1825) applied for a patent of his cotton gin on October 28, 1793; the patent was granted on March 14, 1794, but was not validated until 1807. Whitney's patent was assigned patent number 72X.[18] There is slight controversy over whether the idea of the modern cotton gin and its constituent elements are correctly attributed to Eli Whitney. The popular image of Whitney inventing the cotton gin is attributed to an article on the subject written in the early 1870s and later reprinted in 1910 in The Library of Southern Literature. In this article, the author claimed Catharine Littlefield Greene suggested to Whitney the use of a brush-like component instrumental in separating out the seeds and cotton. Greene's alleged role in the invention of the gin has not been verified independently.[19]

Whitney's cotton gin model was capable of cleaning 50 pounds (23 kg) of lint per day. The model consisted of a wooden cylinder covered by rows of slender wires which caught the fibers of the cotton bolls. Each row of wires then passed through the bars of a comb-like grid, pulling the cotton fibers through the grid as they did.[20] The comb-like teeth of the grids were closely spaced, preventing the seeds, fragments of the hard dried calyx of the original cotton flower, or sticks and other debris attached to the fibers from passing through. A series of brushes on a second rotating cylinder then brushed the now-cleaned fibers loose from the wires, preventing the mechanism from jamming.

Many contemporary inventors attempted to develop a design that would process short staple cotton, and Hodgen Holmes, Robert Watkins, William Longstreet, and John Murray had all been issued patents for improvements to the cotton gin by 1796.[21] However, the evidence indicates Whitney did invent the saw gin, for which he is famous. Although he spent many years in court attempting to enforce his patent against planters who made unauthorized copies, a change in patent law ultimately made his claim legally enforceable – too late for him to make much money from the device in the single year remaining before the patent expired.[22]

McCarthy's gin

editWhile Whitney's gin facilitated the cleaning of seeds from short-staple cotton, it damaged the fibers of extra-long staple cotton (Gossypium barbadense). In 1840 Fones McCarthy received a patent for a "Smooth Cylinder Cotton-gin", a roller gin. McCarthy's gin was marketed for use with both short-staple and extra-long staple cotton but was particularly useful for processing long-staple cotton. After McCarthy's patent expired in 1861, McCarthy type gins were manufactured in Britain and sold around the world.[23] McCarthy's gin was adopted for cleaning the Sea Island variety of extra-long staple cotton grown in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. It cleaned cotton several times faster than the older gins, and, when powered by one horse, produced 150 to 200 pounds of lint a day.[24] The McCarthy gin used a reciprocating knife to detach seed from the lint. Vibration caused by the reciprocating motion limited the speed at which the gin could operate. In the middle of the 20th Century gins using a rotating blade replaced ones using a reciprocating blade. These descendants of the McCarthy gin are the only gins now used for extra-long staple cotton in the United States.[25]

Munger system gin

editFor a decade and a half after the end of the Civil War in 1865, a number of innovative features became widely used for ginning in the United States. They included steam power instead of animal power, an automatic feeder to assure that the gin stand ran smoothly, a condenser to make the clean cotton coming out of the gin easier to handle, and indoor presses so that cotton no longer had to be carried across the gin yard to be baled.[26] Then, in 1879, while he was running his father's gin in Rutersville, Texas, Robert S. Munger invented additional system ginning techniques. Robert and his wife, Mary Collett, later moved to Mexia, Texas, built a system gin, and obtained related patents.[27]

The Munger System Ginning Outfit (or system gin) integrated all the ginning operation machinery, thus assuring the cotton would flow through the machines smoothly. Such system gins use air to move cotton from machine to machine.[28] Munger's motivation for his inventions included improving employee working conditions in the gin. However, the selling point for most gin owners was the accompanying cost savings while producing cotton both more speedily and of higher quality.[29]

By the 1960s, many other advances had been made in ginning machinery, but the manner in which cotton flowed through the gin machinery continued to be the Munger system.[30]

Economic Historian William H. Phillips referred to the development of system ginning as "The Munger Revolution" in cotton ginning.[31] He wrote,

"The Munger innovations were the culmination of what geographer Charles S. Aiken has termed the second ginning revolution, in which the privately owned plantation gins were replaced by large-scale public ginneries. This revolution, in turn, led to a major restructuring of the cotton gin industry, as the small, scattered gin factories and shops of the nineteenth century gave way to a dwindling number of large twentieth-century corporations designing and constructing entire ginning operations."[32]

One of the few (and perhaps only) examples of a Munger gin left in existence is on display at Frogmore Plantation in Louisiana.

Effects in the United States

editPrior to the introduction of the mechanical cotton gin, cotton had required considerable labor to clean and separate the fibers from the seeds.[33] With Eli Whitney's gin, cotton became a tremendously profitable business, creating many fortunes in the Antebellum South. Cities such as New Orleans, Louisiana; Mobile, Alabama; Charleston, South Carolina; and Galveston, Texas became major shipping ports, deriving substantial economic benefit from cotton raised throughout the South. Additionally, the greatly expanded supply of cotton created strong demand for textile machinery and improved machine designs that replaced wooden parts with metal. This led to the invention of many machine tools in the early 19th century.[3]

The invention of the cotton gin caused massive growth in the production of cotton in the United States, concentrated mostly in the South. Cotton production expanded from 750,000 bales in 1830 to 2.85 million bales in 1850. As a result, the region became even more dependent on plantations that used black slave labor, with plantation agriculture becoming the largest sector of its economy.[34] While it took a single laborer about ten hours to separate a single pound of fiber from the seeds, a team of two or three slaves using a cotton gin could produce around fifty pounds of cotton in just one day.[35] The number of slaves rose in concert with the increase in cotton production, increasing from around 700,000 in 1790 to around 3.2 million in 1850.[36] The invention of the cotton gin led to increased demands for slave labor in the American South, reversing the economic decline that had occurred in the region during the late 18th century.[37] The cotton gin thus "transformed cotton as a crop and the American South into the globe's first agricultural powerhouse".[38]

The invention of the cotton gin led to an increase in the use of slaves on Southern plantations. Because of that inadvertent effect on American slavery, which ensured that the South's economy developed in the direction of plantation-based agriculture (while encouraging the growth of the textile industry elsewhere, such as in the North), the invention of the cotton gin is frequently cited as one of the indirect causes of the American Civil War.[39][6][40]

Modern cotton gins

editIn modern cotton production, cotton arrives at industrial cotton gins either in trailers, in compressed rectangular "modules" weighing up to 10 metric tons each or in polyethylene wrapped round modules similar to a bale of hay produced during the picking process by the most recent generation of cotton pickers. Trailer cotton (i.e. cotton not compressed into modules) arriving at the gin is sucked in via a pipe, approximately 16 inches (41 cm) in diameter, that is swung over the cotton. This pipe is usually manually operated but is increasingly automated in modern cotton plants. The need for trailers to haul the product to the gin has been drastically reduced since the introduction of modules. If the cotton is shipped in modules, the module feeder breaks the modules apart using spiked rollers and extracts the largest pieces of foreign material from the cotton. The module feeder's loose cotton is then sucked into the same starting point as the trailer cotton.

The cotton then enters a dryer, which removes excess moisture. The cylinder cleaner uses six or seven rotating, spiked cylinders to break up large clumps of cotton. Finer foreign material, such as soil and leaves, passes through rods or screens for removal. The stick machine uses centrifugal force to remove larger foreign matter, such as sticks and burrs, while the cotton is held by rapidly rotating saw cylinders.

The gin stand uses the teeth of rotating saws to pull the cotton through a series of "ginning ribs", which pull the fibers from the seeds which are too large to pass through the ribs. The cleaned seed is then removed from the gin via an auger conveyor system. The seed is reused for planting or is sent to an oil mill to be further processed into cottonseed oil and cottonseed meal. The lint cleaners again use saws and grid bars, this time to separate immature seeds and any remaining foreign matter from the fibers. The bale press then compresses the cotton into bales for storage and shipping. Modern gins can process up to 15 tonnes (33,000 lb) of cotton per hour.[41]

Modern cotton gins create a substantial amount of cotton gin residue (CGR) consisting of sticks, leaves, dirt, immature bolls, and cottonseed. Research is currently under way to investigate the use of this waste in producing ethanol. Due to fluctuations in the chemical composition in processing, there is difficulty in creating a consistent ethanol process, but there is potential to further maximize the utilization of waste in cotton production.[42][7]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

- ^ "Cotton Gins". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Definition of GIN". Merriam-webster.com.

- ^ a b Roe, Joseph Wickham (1916), English and American Tool Builders, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, LCCN 16011753. Reprinted by McGraw-Hill, New York and London, 1926 (LCCN 27-24075); and by Lindsay Publications, Inc., Bradley, Illinois, (ISBN 978-0-917914-73-7).

- ^ a b c d Lakwete, 1–6.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (February 3, 2018). Economic History of Medieval India, 1200-1500. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131727911 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Kelly, Kelly (July 21, 2020). "What Were the Top 4 Causes of the Civil War". ThoughtCo. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ a b inventors.about.com; "Background on the Cotton Gin", retrieved October 22, 2010.

- ^ Oosterhuis, Derrick; Stewart, Mac; Guthrie, Dave (August 1994). "Cotton Fruit Development: the Boll" (PDF). Cotton Physiology Today. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Bellis, Mary. "The Cotton Gin and Eli Whitney". inventors.about.com. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ "Making Cotton – The Tools of The Trade". Fifteeneightyfour – Academic Perspectives from Cambridge University Press. June 5, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2018.

- ^ Baber, Zaheer (1996). The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-7914-2919-9.

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, p. 53, Pearson Education

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, pp. 53–54, Pearson Education

- ^ Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, p. 54, Pearson Education

- ^ Karl Marx (1867). Chapter 16: "Machinery and Large-Scale Industry". Das Kapital.

- ^ Lakwete, 182.

- ^ Hargrett, Elizabeth; Dobbs, Chris (June 6, 2017). "Cotton Gins". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Who Invented the Cotton Gin and How Did it Impact History?". Archived from the original on March 21, 2014.

- ^ "Catharine Littlefield Greene, Brain Behind the Cotton Gin". Finding Dulcinea. March 4, 2010. Retrieved November 6, 2013.

- ^ Harr, M. E. (1977). Mechanics of particulate media: A probabilistic approach. McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Lakwete, 64–76.

- ^ The American Historical Review by Henry Eldridge Bourne, Robert Livingston Schuyler Editors: 1895 – July 1928; J.F. Jameson and others.; Oct. 1928–Apr. 1936, H.E. Bourne and others; July 1936–Apr. 1941, R.L. Schuyler and others; July 1941– G.S. Ford and others. Published 1991, American Historical Association [etc.], pp 90–101.

- ^ Lakwete, Angela. "Fones McCarthy". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Shofner, Jerrel H.; Rogers, William Warren (April 1962). "Sea Island Cotton in Ante-Bellum Florida". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 40 (4): 378–79.

- ^ Gillum, Marvis M.; Van Doorn, D. W.; Norman, B.M.; Owen, Charles (1994). "Roller Ginning". In Anthony, Stanley W.; Mayfield, William D. (eds.). Cotton Ginner's Handbook. United States Department of Agriculture. p. 244. ISBN 9780788124204. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Aiken, Charles S. (April 1973). "The Evolution of Cotton Ginning in the Southeastern United States". Geographical Review. 63 (2): 205.

- ^ Mann, Sally (2016). Hold still : a memoir with photographs. Little, Brown and Company. pp. 314–317. ISBN 978-0-316-24775-7.

- ^ Atkinson, Edward (June 1, 1880). "Report on the Cotton Manufacturers of the United States". In Department of Interior, Census Office. Report on the Manufacturers of the United States at the Tenth Census. Government Printing Office. pp. 937–984.

- ^ Mann, Sally (2016). Hold still : a memoir with photographs. Little, Brown and Company. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-316-24775-7.

- ^ Aiken, Charles S. (April 1973). "The Evolution of Cotton Ginning in the Southeastern United States". Geographical Review. 63 (2): 205–206.

- ^ Phillips, William (1994). "Making a Business of It: The Evolution of Southern Cotton Gin Patenting, 1831-1890". Agricultural History. 68 (2): 88, 90.

- ^ Phillips, William (1994). "Making a Business of It: The Evolution of Southern Cotton Gin Patenting, 1831-1890". Agricultural History. 68 (2): 85–86.

- ^ Hamner, Christopher. teachinghistory.org, "The Disaster of Innovation", retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Pierson, Parke (September 2009). "Seeds of conflict". America's Civil War. 22 (4): 25.

- ^ Woods, Robert (September 1, 2009). "A Turn of the Crank Started the Civil War." Mechanical Engineering.

- ^ Smith, N. Jeremy (July 2009). "Making Cotton King". World Trade. 22 (7): 82.

- ^ Robert O. Woods (December 28, 2010). "How the Cotton Gin Started the Civil War". The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved September 17, 2020.

- ^ Underhill, Paco (2008). "The cotton gin, oil, robots and the store of 2020". Display & Design Ideas. 20 (10): 48.

- ^ Follett, Richard; Beckert, Sven; Coclanis, Peter A.; Hahn, Barbara (2016). Plantation kingdom: the American South and its global commodities. The Marcus Cunliffe lecture series. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-1940-4.

- ^ Ryan, Joe. "What Caused the American Civil War". Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ "Page 3 : USDA ARS". www.ars.usda.gov. Retrieved November 25, 2021.

- ^ Agblevor, Foster A.; Batz, Sandra; Trumbo, Jessica (February 3, 2018). "Composition and Ethanol Production Potential of Cotton Gin Residues". Biotechnology for Fuels and Chemicals. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ. pp. 219–230. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-0057-4_17. ISBN 978-1-4612-6592-4.

Bibliography

- Lakwete, Angela (2003). Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801873942.

External links

edit- Overview of a Cotton Gin – USDA site

- The Story of Cotton – National Cotton Council of America site

- National Cotton Ginners Association

- US Cotton Gin Industry – EH.Net Encyclopedia of Economic History

- Invention of Cotton Gin – eHistory.com

- Cotton: the fiber of life – includes a schematic diagram illustrating the seed removal process

- Video of manual cotton gin in operation via YouTube

- "The Old Cotton-gin" By John Trotwood Moore · 1910 The Old Cotton-gin