The Art Deco movement of architecture and design appeared in Paris in about 1910–12, and continued until the beginning of World War II in 1939. It took its name from the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925. It was characterized by bold geometric forms, bright colors, and highly stylized decoration, and it symbolized modernity and luxury. Art Deco architecture, sculpture, and decoration reached its peak at 1939 Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, and in movie theaters, department stores, other public buildings. It also featured in the work of Paris jewelers, graphic artists, furniture craftsmen, and jewelers, and glass and metal design. Many Art Deco landmarks, including the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and the Palais de Chaillot, can be seen today in Paris.

Top: Art Deco screen Oasis, made of copper and steel, by Edgar Brandt (1925); Center: "Ocean liner" style apartment building by Pierre Patout (1935); Bottom: Palais de Chaillot (1937) | |

| Years active | 1910–1939 |

|---|---|

Origins

editArt Deco was the result of a long campaign by French decorative artists to gain equal status with the creators of paintings and sculpture. The term "arts décoratifs" was invented in 1875 to give designers of furniture, textiles, and other decoration official status. The Société des artistes décorateurs (Society of decorative artists), or SAD, was founded in 1901, and decorative artists were given the same rights of authorship as painters and sculptors. Several new magazines devoted to decorative arts were founded in Paris, including Arts et décoration and L'Art décoratif moderne. Decorative arts sections were introduced into the annual salons of the Sociéte des artistes français, and later in the Salon d'automne, which played a major role in popularizing the style.[1]

Paris, a city that stands as a living testament to the legacy of Art Deco, reveals its architectural treasures around iconic landmarks like the Eiffel Tower and the Grands Boulevards. The Palais de Chaillot and the Palais de Tokyo showcase the sleekness of Art Deco, while the Folies Bergère and the Grand Rex on the Grands Boulevards exude the movement's elegance. Even in more humble neighborhoods like the 18th district, with the Louxor and the Amiraux swimming pool, Art Deco's influence is evident.

Venturing beyond Paris, the "Garden Cities" of Pré-Saint-Gervais, the Palace at Beaumont-sur-Oise, and the Musée des années 1930 in Boulogne-Billancourt offer a glimpse into the widespread embrace of Art Deco in the Île-de-France region. The tour extends to Boulogne-Billancourt, a hub of interwar prosperity, showcasing the works of Modernist architects like Le Corbusier and Robert Mallet-Stevens.

Parisian department stores and fashion designers also played an important part in the rise of Art Deco. Established firms including the luggage maker Louis Vuitton, silverware firm Christofle, glass designer René Lalique, and the jewelers Louis Cartier and Boucheron, who all began designing products in more modern styles. Beginning in 1900, department stores had recruited decorative artists to work in their design studios. The decoration of the 1912 Salon d'Automne had been entrusted to the department store Printemps.[2] During the same year Printemps created its own workshop called "Primavera". By 1920 Primavera employed more than three hundred artists. The styles ranged from the updated versions of Louis XIV, Louis XVI and especially Louis Philippe furniture made by Louis Süe and the Primavera workshop to more modern forms from the workshop of the Au Louvre department store. Other designers, including Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and Paul Follot refused to use mass production, and insisted that each piece be made individually by hand.

The early Art Deco style featured luxurious and exotic materials such as ebony, and ivory and silk, very bright colors and stylized motifs, particularly baskets and bouquets of flowers of all colors, giving a modernist look.[3]

In 1911, the SAD proposed the holding of a major new international exposition of decorative arts in 1912. No copies of old styles were to be permitted; only modern works. The exhibit was postponed until 1914, then, because of the war, postponed until 1925, when it gave its name to the whole family of styles known as Déco.

Art Deco in architecture was particularly the result of a new technology, the use of reinforced concrete, which allowed buildings to be taller, stronger, and with fewer supporting beams and columns, and to take almost any possible shape. The first reinforced concrete house had been built by François Coignet in 1853. In 1877, another Frenchman, Joseph Monier, received a patent for a system of strengthening concrete with a mesh of iron rods in a grid pattern. Two French architects, Auguste Perret made very innovative use of the new system. Perret used it to construct the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1911–1913), with its vast space without supporting columns; and later, Henri Sauvage used it to construct the first apartment building built like a staircase, each apartment with its own terrace, and another major project, the new building of the La Samaritaine department store.

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–1913)

editThe first major building to be constructed in the Art Deco style was the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–1913). The first design for the building was made by the Belgian Henry van de Velde, who was a major figure of the German Werkbund, an association promoting modern decorative arts. He began work on the design in 1910. Its principal feature was the sober and geometric structure of reinforced concrete. Auguste Perret, the French architect commissioned to build the structure, argued that Van de Velde's design was "materially impossible" and made his own design. After a dispute with the theater owners, Van de Velde resigned and departed, and Perret completed the building following his own plan in April 1913.[4]

The sober geometric forms of the building, decorated with a long frieze by the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, and its facade of concrete covered with marble plaques, was the complete opposite of the ornate Palais Garnier opera house, and caused a scandal. The lobby and the theater interior were equally revolutionary, open and austere, without the columns that blocked the view in many theaters. The decoration by Bourdelle and other artists was stylized and modern. The theater hosted the premieres of newest forms of music and dance the music of the period, The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky and the revolutionary ballets of the Ballets Russes.

-

Antoine Bourdelle, La Danse, facade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, Paris (1912)

-

Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, by Auguste Perret, 15 avenue Montaigne, Paris, (1910–13). Reinforced concrete gave architects the ability to create new forms and bigger spaces.

-

Decoration of the interior with ceiling mural and concrete tiers for seating, without pillars.

The International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts (1925)

editThe International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts held in Paris in 1925, was the largest and most important exhibition of art Deco, and later gave its name to the style. It had first been proposed in 1906, then scheduled for 1912 by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, particularly as a response to the popularity of the designs of the German Werkbund but then was postponed because of the War.[5]

The Exposition was enormous, located between Les Invalides and the Grand Palais, on both sides of the Seine. Even the Pont Alexandre III bridge over the Seine was covered with a row of exhibition halls. The chief architect was Charles Plumet. The Four Towers of the Crafts, by Plumet, marked the center of the Exposition, surrounded by national pavilions and especially pavilions of the major Paris designers and department stores, which had their own design departments, and produced their own furniture and decoration. The pavilions of the department stores were gathered around the esplanade of Les Invalides.

-

Poster for the 1925 Exposition, representing the fusion of art and industry

-

The Grand Esplanade of the 1925 Exposition

-

Pavilion of the Galeries Lafayette department store at the 1925 Exposition

-

Pavilion of the Magasins du Louvre department store

-

The Hotel du Collectionneur, pavilion of the furniture manufacturer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, designed by Pierre Patout.

-

Salon of the Hôtel du Collectionneur from the 1925 International Exposition of Decorative Arts, furnished by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, painting by Jean Dupas, design by Pierre Patout

Henri Sauvage and La Samaritaine (1926–1928)

editThe department store appeared in Paris at the end of the 19th century, and became a major feature of the early 20th century. The original La Samaritaine store was built in 1905 by architect Frantz Jourdain in the Art Nouveau style. In 1925 the store was enlarged with an Art Deco building facing the Seine, designed by Henri Sauvage. Sauvage was one of the major figures of Paris Art Deco; his other important works included the Studio Building and the Majorelle Building, built for the furniture designer Louis Majorelle, as well as the innovative apartment building at 26 rue Vavin (6th arr.) (1912–1914), which arranged its apartments in steps, each having its own terrace. (1906). This design was used by Sauvage and other architects in the period.[6]

-

Art Deco building of La Samaritaine department store (1926–28)

-

La Samaritaine, building 2 (1928)

-

Building 3 of La Samaritaine (1930)

Churches

editSeveral new churches were built in Paris between the wars, in styles that mixed Art Deco features, such as stylized towers, the use of reinforced concrete to create large open spaces, and decorative murals in a Deco style, frequently combined with features of Byzantine architecture, like that of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur, which was popular at the time. The Église du Saint-Esprit, (1928–32), located at 186 Avenue Daumesnil in the 12th arrondissement, was designed by Paul Tournon. It has a modern exterior, made of reinforced concrete covered with red brick and modern bell tower 75 meters high, but the central feature is a huge dome, 22 meters in diameter. The design, like that of the Basilica of Sacré-Cœur, was inspired by Byzantine churches. The interior was decorated with murals by several notable artists, including Maurice Denis. .[7] The Church of Sainte-Odile at 2 Avenue Stephane-Mallarmé (17th arrondissement), by Jacques Barges (1935–39) has a single nave, three neo-Byzantine cupolas, and the highest bell tower in Paris, 72 meters tall.[8]

-

Church of Saint-Esprit, 186 avenue Daumesnil (12th arr.) by Paul Tournon (1928–32), has a Deco exterior and massive reinforced concrete Byzantine dome.

-

Art Deco murals in the interior of the Church of Saint-Esprit (1928–32)

-

Sainte-Odile, Paris at 2 avenue Stephane-Mallarmé (17th) (1935–39) has the highest bell tower in Paris

-

Sculptural decoration and iron work of the Church of Saint-Odile

-

Deco stained glass of the Church of Sainte-Odile, Paris

Theaters and movie palaces

editPalatial movie theaters in the Art Deco style appeared in Paris in the 1920s. The MK3 theater at 4 rue Belgrande (20th arr,) by Henri Sauvage (1920) preserves its decorative murals on the facade.[9] Le Louxor, from 1921, in a sort of neo-ancient Egyptian style, by architect Henri Zipcy. The interior features colorful neo-Egyptian mosaics by Amédée Tiberi. It was restored in 2013, and is now an historic monument. The largest and most Deco theater still existing from the period is the Grand Rex cinema1 (boulevard Poissonière no. 1, 2nd arr.)) built in 1932 by the French architect Auguste Bluysen with the American engineer John Eberson. It is one of the largest theaters in Europe, seating 3100 persons. The theater interior was decorated by a prominent Deco designer, Maurice Dufrêne. It seats 2100 persons. It has undergone a major renovation, and now is used for concerts and other events as well as films.[10]

-

Folies Bergère (1926) after renovation to original appearance

-

The MK2 Movie Theater at 4 rue Belgrande by Henri Sauvage (1920)

-

Le Louxor movie theater at 150 Boulevard de Magenta by Henri Zipcy (1921)

-

Mosaics with Egyptian motifs in Le Louxor movie theater (1921)

Apartment buildings and residences

editHenri Sauvage was one of the most inventive of designers of apartment buildings. He was particularly adept at covering the reinforced concrete facades with ceramic tile. In 1911 he built the Majorelle Building for the furniture designer Louis Majorelle, with a reinforced concrete facade covered with ceramics, giving it a sleek, modern appearance. He introduced the stepped building to Paris, an apartment building where each apartment was set back from the one below, in order that each would have its own terrace.

Additionally, one of the highlights of the exploration is the Maison de Verre, a Modernist masterpiece designed by Pierre Chareau and Bernard Bijvoet. Tucked away near Saint-Germain-des-Prés, this private residence exemplifies the avant-garde spirit of Art Deco, with its translucent glass block façade and innovative design elements.

-

The Majorelle building by Henri Sauvage at 126 rue de Provence (8th arrondissement), built for Louis Majorelle (1911)

-

Apartment building in steps by Henri Sauvage, 26 rue Vavin (8th arr.) (1912–1914)

-

The Studio Building at 65 rue La Fontaine by Henri Sauvage (1926–28)

-

Residence and studio of architect Auguste Perret in Boulogne-Billancourt (1929)

The Pacquebot style

editThe Pacquebot, or Ocean Liner style, was inspired by the form of French Transatlantic ocean liners, such as the SS Normandie. The most famous example is an apartment building at 3 boulevard Victor (15th arrondissement), built in (1934–1935) by Pierre Patout, in the same period that he created the interior decor for the Normandie. The building was constructed on an unusually-shaped lot, which narrowed from twelve meters wide to just three meters at the "bow" of the building. Patout had his own apartment, on three floors, in this part of the building.[11]

Pierre Patout's own house and studio, built earlier in 1927–28 at 2 Rue Gambetta in the Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt, also showed elements of Pacqueboat, including the railing around the top "deck" or terrace. He also contributed to the reconstruction of the Galeries Lafayette department store in 1932–1936.[11]

-

Residence and studio of Pierre Patout in Boulogne-Billancourt (1927–28)

-

Dining room of the SS Normandie designed by Pierre Patout (1934–35)

-

Apartment building by Pierre Patout in the Pacquebot or ocean liner style, 3 boulevard Victor (15th arrondissement), (1934–35)

Swimming pools

editThe most famous Art Deco swimming pool in Paris is the Piscine Molitor, next to the Bois de Boulogne park, and between Stade Roland Garros and Parc des Princes. The complex designed by architect Lucien Pollet to resemble the deck of ocean liner, with three levels of "cabins" around the outdoor pool. It was completed in 1929 and inaugurated by Olympic swimmers including Aileen Riggin and Johnny Weissmuller. It was also the site for the first unveiling of the French bikini swimsuit by designer Louis Réard in July 1946. In the winter it was transformed into an ice skiing rink. Besides its nautical architecture, it features Art Deco stained glass by Louis Barillet. The complex fell into disrepair and was closed in 1989 with the intention of building a housing project on the site. After years of disuse, dispute and vandalism, it was declared an historical site and underwent major renovation. It reopened in 2013, following the original style, as part of a larger commercial and hotel complex.[12]

-

The Piscine Molitor (1929) after its closure in 1989 and before the 2015 renovation

-

Deco stained glass at the Piscine Molitor by Louis Barillet (1929)

-

The renovated outdoor pool of the Piscine Molitor

Late Art Deco (1930–1939)

editThe global economic depression that began in 1929 soon had an impact on architecture and decoration in Paris. Buildings became less ornate, less extravagant, more streamlined, with a return to some elements of classicism and tradition, such as neoclassical colonnades. It was a period of strikes, turmoil and confrontation.[13]

Deco vs. Modernism

editIn 1929, the Art Deco movement in France was split into two currents by the breakaway of the Union des Artistes Moderne (UAM) from the more traditional Société des Artistes Decorateurs. This new group proposed more functional architecture, furniture and decoration, mass production, simpler materials and no decoration at all. The members included René Herbst, Jacques Le Chevalier, and Robert Mallet-Stevens, its first president. The movement was soon joined by other architects and designers, including Le Corbusier, the silversmith Jean Puiforcat, Pierre Chareau, and Eileen Gray. The Paris houses built by Mallet-Stevens on what is now Rue Mallet-Stevens (XIVth arrondissement) (1927–29) and his very spare steel furniture, illustrate the aesthetics of the movement. The residence of the Martel Brothers, along the "Glass House" of Pierre Chareau (1928–31) was the beginning of movement of Modern architecture in Paris

-

Villa Martel by Robert Mallet-Stevens on Rue Mallet-Stevens (1929)

-

The Glass House by Pierre Chareau 31, rue Saint-Guillaume VIIe arrondissement, (1928–31)

-

Chair by Robert Mallet-Stevens (1929–31)

-

E-1027 table by Eileen Gray

The 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition

editThe Paris Colonial Exposition, held for six months in 1931 in the Bois de Vincennes, was designed as a showcase of France's overseas colonies, their products and their culture, and was also a showcase of Art Deco. The Netherlands, Belgium, Italy, Japan, Portugal, the United Kingdom, and the United States all had pavilions. It was particularly celebrated for its extensive use of flood lights and colorful illumination, a novelty at the time, used to great effect in the "Cactus" fountain the centerpiece of the Exposition. The principal Art Deco legacy of the Exposition is the Palais de la Porte Dorée, now the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration, which was constructed from 1928 to 1931 by the architects Albert Laprade, Léon Bazin and Léon Jaussely. The facade has large bas-reliefs (by sculptor Alfred Janniot portraying ships, oceans, and the wildlife of Africa. The original ethnographic exhibits were transferred to the Musée du quai Branly in 2003, and it now houses the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration, a museum of immigration and a major aquarium.

The Palais de la Porte Dorée has housed a succession of ethnological museums, starting with the colonial exhibition of 1931, which was renamed in 1935 the Musée de la France d’Outre-mer, then in 1960 the Musée des Arts africains et océaniens, and finally in 1990 the Musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie. In 2003 these collections were merged into the Musée du quai Branly, and in its place the building now houses the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration.

-

The illuminated Cactus fountain

-

The Colonial Exposition at night

-

Salon with murals in the Cité nationale de l'histoire de l'immigration,

The 1937 Paris International Exposition

editThe major design event of the period in Paris was the Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne, overlooking the Eiffel Tower. It was the seventh and last international exposition of its kind to be held in Paris. Fifty countries participated, including Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, whose pavilions faced each other. Some modernist architecture was on display, including the Spanish pavilion by Josep Lluís Sert, where Picasso's painting Guernica was presented; the Pavilion of Light and Electricity, by Robert Mallet-Stevens, and the pavilion of Finland, with wood-covered walls, by Alvar Aalto. Le Corbusier had a small pavilion of his own, made of canvas, at the edge of the Exposition.[14]

The Palais de Chaillot, by Jacques Carlu, Louis Hippolyte Boileau and Léon Azéma, combined elements of classicism and modernism, as did the nearby Palais de Tokio (now the Paris Museum of Modern Art), by André Aubert, Paul Viard, and Marcel Dastugue.The large gallery and the reception rooms of the Paris municipal council in the Palais de Chaillot were decorated with a monumental lacquered decoration of more than 120 panels produced by Gaston Suisse. This set presented "art and technique" in France in 1937.[15]

A third building of major importance was the Museum of Public Works (now the Economic Council, by Auguste Perret. They all had the major characteristics of this period of Art Deco architecture; smooth concrete walls covered with stone plaques, sculpture on the facade, and murals on the interior walls.

The journey through Art Deco's Paris culminates at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, home to a stellar collection that includes objects from the 1925 Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes. Here, visitors can witness the evolution of Art Deco through the iron gates of Edgar Brandt and the original furniture designs of Pierre Chareau.

-

The Palais de Chaillot (1937)

-

The Palais de Tokyo by André Aubert, Paul Viard, and Marcel Dastugue (1937)

-

Stairway of the Economic, Social and Environmental Council, by Auguste Perret (with his portrait over the stairs) (1937)

-

Gaston Suisse Normandie and aviation detail of the monumental lacquered decoration in the Palais de Chaillot[17]

Furniture and decoration

editColor and exoticism (the 1920s)

editArt Deco Furniture and decoration in Paris before 1914 featured bold colors and geometric floral designs, borrowed from diverse sources ranging from the Ballets Russes to cubism and Fauvism. The First World War put an end to the more lavish style, and stopped almost all construction and decoration. As soon as the war was over, two prominent artists, Louis Süe and André Mare, founded the Compagnie des Arts français, a collaborative venture of decorative artists, with Süe as artistic director and Mare as technical director. Their purpose was the renewal of French decorative arts. Other members included André Vera and his brother Paul Vera, and Charles Dufresne. They opened a gallery in 1920 on rue de Faubourg-Saint-Honoré which displayed furniture, lamps, glassware, textiles and other new products, including many designed to be produced in series. Later the group was joined by artists in more modernist styles, including Francis Jourdain and Charlotte Perriand. The Compagnie was a major promoter in the advance of Parisian Art Deco.[18]

Designers in this period used the most exotic and expensive materials they could find. The painter and decorator Paul Iribe made a delicate commode in 1912 of mahogany black marble, and sharkskin. In about 1925 André Groult made a small cabinet in an organic shape, entirely covered with white sharkskin. He decorated the first-class cabins on the ocean liner Normandie.[19]

The furniture designed by Louis Süe and Andre Mare of Compagnie des Arts Francais was finely crafted and lavish. The buffet pictured in the gallery below (1920–1921), now in the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, is made of Mahogany, gilded bronze, and marble.

Another major figure in Paris interior decoration in the 1920s was Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann. He had his own pavilion at the 1925 Exposition. His furniture was noted for its use of rare and expensive woods and other materials, such as ivory. The simple-looking "Duval" cabinet, pictured below, designed in 1924 and probably made in 1926, is made of Brazilian rosewood, ivory, amboyna burl, mahogany, oak, and little plywood. The "Tibittant" desk by Ruhlmann illustrated below, made in 1923, is a fall-leaf desk with a core of plywood covered with oak, poplar, mahogany, and Macassar ebony veneers inside and out. It has ivory inlays, feet, and knobs, silk tassels, a leather interior writing surface, and aluminum leaf and silver gilding. It is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[20]

-

Display at Salon d'Autumne (1913)

-

Commode of mahogany, black marble and sharkskin by Paul Iribe (about 1919)

-

Paravent Les Faunes (c. 1920), by the Compagnie des Arts Francais, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

-

The Glass Salon, designed by Paul Ruaud, furniture by Eileen Gray (1922)

-

Small cabinet covered with sharkskin, by André Groult (about 1925)

-

Buffet by the Compagnie des Arts Francais (1920–21)

-

Corner cabinet by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (about 1923), Brooklyn Museum

-

Tibbitant desk by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (1923) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

"Duval" cabinet by Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann (designed 1924, probably made 1926), Metropolitan Museum

-

Boudoir of apartment of Jeanne Lanvin by Armand-Albert Rateau (c. 1925), Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

-

Office designed by Pierre Chareau (about 1925), Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

Functional furniture - the 1930s

editThe 1930s, under the influence of Constructivism and other more modernist styles, furniture and excoriation became more geometric and functional. Examples were the work of Pierre Chareau and Jules Leleu. The style broke into two parts, one devoted to more traditional forms, fine craftsmanship and luxurious materials, the other to more austere forms and experiments with new materials, such as aluminum and steel.

-

Furniture by Jules Leleu (Musée des Années 30 in Boulogne-Billancourt)

-

Salon by Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann for sculptor Joseph Bernard (c. 1930)

-

Dressing table by René Herbst for the Princess Aga Khan (1932), (Musée des Arts Décoratifs)

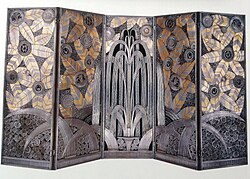

Screens

editScreens were an important part of Art Deco design, allowing rooms to be easily divided, opened up, or given a different look. They were usually combined with carpets in a similar style. Most screens were painted on fabric or wood. A highly unusual Art Deco screen is Oasis, made of iron and copper by engineer and metal worker Edgar Brandt for display at the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts.

Another influential screen maker was Jean Dunand, who mastered the ancient art of Japanese lacquer painting, and also worked with copper and other unusual materials. His screen Fortissimo, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is made of lacquered wood, eggshell, mother-of-pearl, and gold leaf.

-

Screen by Armand-Albert Rateau (1921–22), (Musée des Arts Décoratifs Paris)

-

Art Deco screen Oasis, msde of copper and steel, by Edgar Brandt (1925)

-

Fortissimo, a screen by Jean Dunand (1924–26), of lacquered wood, eggshell, mother-of-pear, and gold leaf. (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Screen by Gaston Suisse, Black Chinese lacquer and graphite inlays. Abstract geometric decor in silver lacquer.circa1925,[21] Exposition: 1925, Quand L'art Déco séduit le monde.Cité de l'architecture, Palais de Chaillot, Paris

Silverware

editJean Puiforcat (1897–1945) was the major figure in Paris Art Deco silverware. The son of a silversmith, he was also a sculptor. He had his first success in 1923 at the Salon des Decorateurs in Paris, where he combined silver with lapis lazuli. He made only individual items, not series, and often combined them with semi-precious stones. A major collection of his work and silverware he collected was donated to the Louvre by Stavros Niarchos.[19]

-

Teapot of silver and lapis lazuli by Jean Puiforcat (1922) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Soup tureen, silver and gold by Jean Puiforcat (1937), Metropolitan Museum

Glass Art

editThe domain of Art Deco glass art in Paris was dominated by René Lalique, who had first made his reputation at the 1900 Paris Exposition, when he was the first jeweler use glass in jewelry. Besides table glassware, he designed a wide variety of glass art objects, both practical and decorative, including glass hood ornaments for luxury automobiles. His major projects included decorating the dining room of the ocean liner Paris (1920), making table service for the French President (1922), and an illuminated glass fountain in a central position at the 1925 Paris Exposition of Decorative Arts. Beginning in 1925 he modified his style from floral fantasies to more geometric and simpler designs. In the 1930s he decorated the dining room of the ocean liner SS Normandie.[22]

-

Firebird by René Lalique (1922) (Dayton Art Institute)

-

Lalique vase with female figures (1930) (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris)

-

Lalique belt buckle (1932) (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

-

Greyound hood ornament by René Lalique (1935) (Baltimore Museum of Art)

-

Cup and vase by Maurice Marinot (1932)

Decorative objects

edit-

Cigarette case of snakeskin and gold by Pierre Legrain (1925) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Cigarette case of leather and gold leaf by Pierre Legrain (1922) (Metropolitan Museum)

-

Art Deco watch, cigarette cases, and pillbox made by the Paris firm of Chaumet (1926–30) (Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris)

-

Boucheron (1925), a gold buckle set with diamonds and carved onyx, lapis lazuli, jade, and coral (Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris)

-

Gaston Suisse, Chinese lacquer square box[23] circa1929

Sculpture

editArt Deco sculpture was by definition and function decorative, usually placed on the facades or in close proximity to buildings in the style to complement them. Some Paris sculptors, such as Antoine Bourdelle, created both Deco sculpture and more traditional gallery or monumental pieces. Bourdelle was the first major Art Deco sculptor, for the friezes and other works he created to decorate the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, though much of his other work of the time was more traditional sculpture.

Demétre Chiparus, born in Romania, became one of the most successful Deco sculptors in Paris, and showed his work regularly at the Salon des Artistes Français between 1914 and 1928. He specialized in small statuettes called chryselephantines, depicting women with face and hands made of ivory clad in costumes of bronze. He depicted dancers, acrobats, and other exotic figures.[24]

Monumental sculpture complemented the facade and parvis of the Palais de Chaillot of the 1937 Paris Exposition, including a statue of "The Fruit" by Félix-Alexandre Desruelles at the Palais de Chaillot (1937)

-

Apollo and the Muses, a bas-relief for the facade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1910–1912)

-

La France by Antoine Bourdelle (1922)

-

The Fruit by Félix-Alexandre Desruelles at the Palais de Chaillot (1937)

-

Tanara by Demétre Chiparus

-

Les Girls by Demétre Chiparus, of bronze and ivory, on a quartz and marble base (1920s) Art Deco Museum in Moscow

Murals

edit-

Model by Maurice Denis for the mural inside the dome of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées (1911–1912)

-

Murals in the entrance of the Théâtre national de Chaillot (1937)

Posters and graphic arts

editThe graphic arts, particularly fashion magazine covers and illustrations, played an important role in popularizing the style, as posters had earlier done for the Art Nouveau. Major illustrators included Paul Iribe and Georges Lepape, whose fashion illustrations for Vogue magazine helped popularize the designs of Paul Poiret. Lepape's illustrations were also a major feature of the fashion magazine Gazette de Bon Ton. Reproduced in the United States, the French fashion illustrations created a great demand for the new French styles. Lepape also designed costumes and sets for the theater and ballet. It is also the inspiration in official emblem of the 2024 Summer Olympics and 2024 Summer Paralympics in Paris.[25]

-

Fashion illustration of designs of Paul Poiret by Paul Iribe (1908)

-

Illustration of Poiret fashion by Paul Iribe (1912)

-

Cover of Vanity Fair by Georges Lepape (1919)

-

Moulin Rouge program by Charles Gesmar (1925)

-

Postcard packet from the 1937 Paris Exposition

Conclusion

editAs the journey concludes, one cannot overlook the lasting impact of Art Deco on Paris. The Museum of Decorative Arts, nestled in the Louvre, houses a permanent exhibit celebrating 1930s Art Deco modernity, showcasing the movement's sharp edges, sleek surfaces, and dramatic intersections of form and function.

Paris, despite its distinctively different look, played a pivotal role in launching the Art Deco style onto the global stage. The 1925 World’s Fair, Exposition Internationale des Arts Decoratifs et Industriels Modernes, served as a catalyst, introducing the world to the bold, angular, and streamlined elegance that defines Art Deco.

From the Grand Rex cinema to the Palais de Chaillot, from the Grand Palais to the intimate corners of private residences, Art Deco's enchantment continues to captivate those who explore the magic and monumentality embedded in every corner of this enduring architectural and design legacy.

Art Deco in Paris museums

editThe following museums in Paris have notable collections of Art Deco furniture and decorative items.

- Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris

- Musée d'Orsay

- Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris (Palais de Tokyo) - Art Deco Room

- Musée des Années Trente in the western Paris suburb of Boulogne-Billancourt, Station Marcel Sembat (Paris Métro) Line Nine

Notes and citations

edit- ^ Laurent (2002), pp. 165–170.

- ^ "Salon d'Automne 2012, exhibition catalogue" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-01. Retrieved 2019-09-13.

- ^ Laurent (2002), pp. 165–171.

- ^ Texier (2019), p. 7.

- ^ Texier (2019), pp. 10–14.

- ^ Poisson (2009), pp. 38–39.

- ^ Dumoulin, Aline, Églises de Paris (2010), Éditions Nassin, ISBN 978-2-7072-0683-1, pages 166–167.

- ^ Texier (2012), p. 129.

- ^ Poisson (2009), p. 318.

- ^ Texier (2019), pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Poisson (2009), p. 292.

- ^ Base Mérimée: Piscine Molitor, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Bony (2012), pp. 110–111.

- ^ Bony (2012), pp. 110–115.

- ^ Alves, Julie (2020). Gaston SUISSE (1896 – 1988) La commande du décor Art et Technique pour la Grande Galerie du Commissariat Général de l’Exposition internationale de 1937 au Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris (in French). Université Panthéon Sorbonne Paris 1 MASTER 2 HISTOIRE DU PATRIMOINE ET DES MUSEES UFR 03- Histoire de l’Art / UFR 09-Histoire.

- ^ Texier (2019), p. 46.

- ^ Suisse, Gaston. "International Exposition of Art & Technology, Paris 1937". Archived from the original on 2021-08-19.

- ^ Texier (2019), pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b Cabanne (1986), p. 228.

- ^ Description from the Metropolitan Museum site.[full citation needed]

- ^ exhibition catalog (2013). 1925 Quand l'art déco séduit le monde (in French). Paris France: Éditions Norma. p. 259. ISBN 978-2-9155-4258-5.

- ^ Cabanne (1986), pp. 205–206.

- ^ Capstick-Dale, Rodney and Diana (2016). Art Deco Collectibles. Fashionables objets from the jazz age. Thames & Hudson. p. 12. ISBN 0500518319.

- ^ Cabanne (1986), p. 181.

- ^ Cabanne (1986), p. 213.

Bibliography

editMedia related to Art Deco architecture in Paris at Wikimedia Commons

- Art Deco a la francaise. ArtDeco.org. (n.d.). https://www.artdeco.org/paris-art-deco

- Bony, Anne (2012). L'Architecture Moderne.

- Cabanne, Pierre (1986). Encyclopedie Art Deco (in French). Somogy. ISBN 2-85056-178-9.

- France.fr. (2023, February 1). Art Deco in Paris and the ile-de-france. France.fr : Actualités, destinations et infos du tourisme en France. https://www.france.fr/en/paris/article/art-deco-paris-and-ile-france

- Laurent, Stephane (2002). "L'artiste décorateur". Art Deco, 1910–1939. By Charlotte Benton; Tim Benton; Ghislain Wood. Renaissance du Livre. pp. 165–171.

- Pile, John F. (2005). A history of interior design. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-418-6. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

- Poisson, Michel (2009). 1000 Immeubles et monuments de Paris (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-539-8.

- Texier, Simon (2012). Paris: Panorama de l'architecture (in French). Parigramme. ISBN 978-2-84096-667-8.

- Texier, Simon (2019). Art Déco. Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 978-27373-8172-0.

- Alastair Duncan (1992). Art Deco Furniture: The French Designers.Thames and Hudson

- Alastair Duncan (1988). The Encyclopedia of Art Deco. Headline book ISBN 978-0-52524-613-8

- Rodney and Diana Capstick-Dale (2016). Art Deco Collectibles, fashionable objets from the jazz age, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500518319

- writer, G. (2021, August 29). Art deco Paris. The Good Life France. https://thegoodlifefrance.com/art-deco-paris/