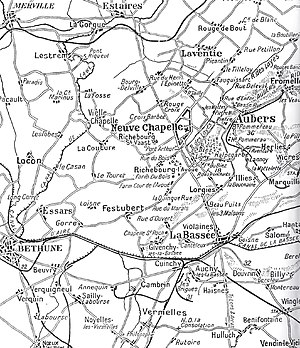

The Battle of Aubers (Battle of Aubers Ridge) was a British offensive on the Western Front on 9 May 1915 during the First World War. The battle was part of the British contribution to the Second Battle of Artois, a Franco-British offensive intended to exploit the German diversion of troops to the Eastern Front. The French Tenth Army was to attack the German 6th Army north of Arras and capture Vimy Ridge, preparatory to an advance on Cambrai and Douai. The British First Army, on the left (northern) flank of the Tenth Army, was to attack on the same day and widen the gap in the German defences expected to be made by the Tenth Army and to fix German troops north of La Bassée Canal.

| Battle of Aubers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Battle of Artois on the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Aubers Ridge and Festubert, 1915 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 9 May: 11,161 | 9 May: 902 (partial) | ||||||

The attack was an unmitigated disaster on the part of the British. No ground was gained, no tactical advantage was gained, and they suffered more than ten times the number of casualties as the Germans. To make matters worse the battle precipitated a political crisis back home, which became the Shell Crisis of 1915.

Background

editThe battle was the initial British component of the combined Anglo-French offensive known as the Second Battle of Artois.[a] The French commander-in-chief, Joseph Joffre, had enquired of Sir John French, commander of the British Expeditionary Force, if British units could support a French offensive into the Douai Plain around late April or early May 1915. The immediate French objectives were to capture the heights at Notre Dame de Lorette and Vimy Ridge.[2] The British First Army was further north, between La Bassée and Ypres in Belgium. It was decided that the British forces would attack in the southern half of their front line, near the village of Laventie. The objective, in the flat and poorly drained terrain, was Aubers Ridge an area of slightly higher ground 2–3 km (1.2–1.9 mi), containing the villages of Aubers, Fromelles and Le Maisnil. The area had been attacked in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle two months earlier.[3] The battle marked the second use of specialist Royal Engineer tunnelling companies, when men of 173rd Tunnelling Company tunnelled under no man's land and planted mines under the German defences, to be blown at zero hour.[4]

Prelude

editGerman defensive measures

editThe Battle of Neuve Chapelle had shown that one breastwork was insufficient to stop an attack and the fortifications opposite the British were quickly augmented. Barbed-wire entanglements were doubled and trebled and 5 ft (1.5 m) deep breastworks were increased to 15–20 ft (4.6–6.1 m) broad, with traverses and a parados (a bank of earth behind the trench to provide rear protection). Each battalion had two machine-guns and these were emplaced at ground level, set to sweep no man's land from flanking positions. A second breastwork (the Wohngraben) begun as part of a general strengthening of the Western Front earlier in the year, about 200 yd (180 m) behind the front line was nearly finished. The Wohngraben had dugouts underneath to accommodate 20–30 men and was connected to the front breastwork by communication trenches. Close to the front, the communication trenches were solidly built with concrete shelters and were ready to be used as flanking trenches against a breakthrough. The second line of defence was far enough back from the front line for shells falling on one not to affect the other and the front breastwork became a line of sentry-posts. The second line became the accommodation for the main garrison, which was to move forward during an attack to hold the front line at all costs.[5]

About 700–1,000 yd (640–910 m) back from the front breastwork, a line of concrete machine-gun posts known as the Stützpunktlinie had been built, about 1,000 yd (910 m) apart, as rallying points for the infantry if the front position was broken through. Opposite Rue du Bois, machine-gun posts were built at La Tourelle, Ferme du Bois (Apfelhof) and Ferme Cour d'Avoué (Wasserburg). Battalion frontages were held by two companies of about 280 men on a frontage of 800–1,000 yd (730–910 m), with one company in support 2,000 yd (1,800 m) to the rear and the fourth company in reserve another 2,000–4,000 yd (1.1–2.3 mi; 1.8–3.7 km) back. The new communication trenches were arranged so that the support companies could easily block a break-in from the flanks; most of the field artillery of 6–12 four-gun field batteries and several heavy batteries in each division, were on Aubers Ridge 2,500–4,000 yd (1.4–2.3 mi; 2.3–3.7 km) behind the front line, between Lorgies and Gravelin.[6] A second line of gun positions between La Cliqueterie Farm, Bas Vailly, Le Willy and Gravelin, about 2,500 yd (1.4 mi; 2.3 km) behind the forward battery positions, had been built so that the guns could be moved back temporarily, until enough reinforcements had arrived from Lille and La Bassée to counter-attack and reoccupy the front line.[7]

Battle

editIntelligence about the work to improve German positions was not available or given insufficient attention where known.[8] No surprise was achieved because the British bombardment was insufficient to break the German wire and breastwork defences or knock out the German front-line machine-guns. German artillery and free movement of reserves were also insufficiently suppressed.[8] Trench layout, traffic flows and organisation behind the British front line did not allow for easy movement of reinforcements and casualties. British artillery and ammunition were in poor condition: the first through over-use, the second through faulty manufacture.[9] It soon became impossible to tell where British troops were and accurate artillery fire was impossible.[10]

Air operations

editThree squadrons of the 1st Wing Royal Flying Corps (RFC) were attached to the First Army for defensive patrols for four days before the attack, to deter enemy reconnaissance. During the attack they were to conduct artillery observation and reconnaissance sorties and bomb German rear areas, railway junctions and bridges further afield.[11]

Aftermath

editAnalysis

editThe battle was an unmitigated disaster for the First Army. No ground was won and no tactical advantage gained. It is doubted if it had the slightest positive effect on assisting the main French attack 15 mi (24 km) to the south.[12] The battle was renewed slightly to the south, from 15 May as the Battle of Festubert.[13] In the aftermath of the Aubers Ridge failure, the war correspondent of The Times, Colonel Charles à Court Repington, sent a telegram to his newspaper highlighting the lack of high-explosive shells, using information supplied by Sir John French; The Times headline on 14 May 1915 was: "Need for shells: British attacks checked: Limited supply the cause: A Lesson From France". This precipitated a political scandal known as the Shell Crisis of 1915.[14]

Casualties

editHans von Haeften, an official history editor of the Reichsarchiv, recorded c. 102,500 French casualties from 9 May to 18 June, 32,000 British casualties and 73,072 German casualties for the operations of the Second Battle of Artois.[15] The British Official Historian, James Edmonds recorded 11,619 men British casualties.[16] Edmonds wrote that the German Official History made little reference to the battle but in 1939 G. C. Wynne wrote that Infantry Regiment 55 had 602 casualties and Infantry Regiment 57 lost 300 casualties.[17][b]

Awards

editFour Victoria Crosses were awarded for actions in the Battle of Aubers

- David Finlay, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)[19]

- John Ripley, Black Watch (Royal Highlanders)[20]

- Charles Sharpe, Lincolnshire Regiment[21]

- James Upton, Sherwood Foresters (Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Regiment)[22]

Notes

edit- ^ British Order of Battle: I Corps, 1st Division and 47th (1/2nd London) Division. IV Corps 7th Division and 8th Division. Indian Corps, 3rd (Lahore) Division and 7th (Meerut) Division, First Wing, RFC.[1]

- ^ Four time Wimbledon tennis champion Anthony Wilding from New Zealand, was one of the fatalities of the battle, killed on 9 May when a shell exploded on the roof of his dug-out.[18]

Footnotes

edit- ^ James 1990, p. 7.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 31.

- ^ Wynne 1976, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Wynne 1976, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rogers 2010, p. 30.

- ^ a b Edmonds 1928, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 33, 37.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 41.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 10.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, pp. 44–82.

- ^ Holmes 2004, pp. 287–289.

- ^ Haeften 1932, pp. 93, 96.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 39.

- ^ Wynne 1976, p. 43.

- ^ Myers 1916, p. 286.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 29.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 27.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 35.

- ^ Edmonds 1928, p. 34.

References

edit- Edmonds, J. E. (1928). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Battles of Aubers Ridge, Festubert, and Loos. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents By Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962526.

- Haeften, Hans von, ed. (1932). Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918, Militärischen Operationen zu Lande Achter Band: Die Operationen des Jahres 1915; Die Ereignisse im Westen im Frühjahr und Sommer, im Osten vom Frühjahr bis zum Jahresschluß Band 2 [The World War 1914 to 1918 Military Land Operations Volume Eight. The Operations of 1915; Events in the West in the Spring and Summer, in the East from Spring to the End of the Year]. Vol. VIII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Mittler. OCLC 838300036. Retrieved 30 December 2013 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich (The Upper Austrian Provincial Library).

- Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84614-7.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2.

- Myers, A. W. (1916). Captain Anthony Wilding. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 1203033. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Rogers, D., ed. (2010). Landrecies to Cambrai: Case Studies of German Offensive and Defensive Operations on the Western Front 1914–17. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-906033-76-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Further reading

edit- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front, 1915: Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. Vol. II. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1964) [1962]. Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War (2nd corr. online ed.). Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 59609928. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2018 – via Government of Canada: Publications.