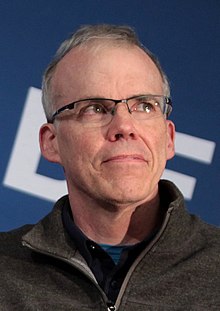

William Ernest McKibben (born December 8, 1960)[1] is an American environmentalist, author, and journalist who has written extensively on the impact of global warming. He is the Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College[2] and leader of the climate campaign group 350.org. He has authored a dozen books about the environment, including his first, The End of Nature (1989), about climate change, and Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? (2019), about the state of the environmental challenges facing humanity and future prospects.[3]

Bill McKibben | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | William Ernest McKibben December 8, 1960 Palo Alto, California, U.S. |

| Education | Harvard University (BA) |

| Notable awards | Gandhi Peace Award Right Livelihood Award |

| Spouse | Sue Halpern |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

In 2009, he led 350.org's organization of 5,200 simultaneous demonstrations in 181 countries. In 2010, McKibben and 350.org conceived the 10/10/10 Global Work Party, which convened more than 7,000 events in 188 countries,[4][5] as he had told a large gathering at Warren Wilson College shortly before the event. In December 2010, 350.org coordinated a planet-scale art project, with many of the 20 works visible from satellites.[6] In 2011 and 2012 he led the environmental campaign against the proposed Keystone XL pipeline project[7] and spent three days in jail in Washington, D.C. Two weeks later he was inducted into the literature section of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[8]

He was awarded the Gandhi Peace Award in 2013.[9] Foreign Policy magazine named him to its inaugural list[10] of the 100 most important global thinkers in 2009 and MSN named him one of the dozen most influential men of 2009.[11] In 2010, The Boston Globe called him "probably the nation's leading environmentalist"[12] and Time magazine book reviewer Bryan Walsh described him as "the world's best green journalist".[13] In 2014, he was awarded the Right Livelihood Award for "mobilizing growing popular support in the USA and around the world for strong action to counter the threat of global climate change."[14] He has been mentioned as a possible future Secretary of the Interior or Secretary of Energy should a progressive be elected President.[15]

Early life

editMcKibben was born in Palo Alto, California.[1][16] His family later moved to the Boston suburb of Lexington, Massachusetts, where he attended high school.[17] His father, who once, in 1971, had been arrested during a protest in support of Vietnam veterans against the war, wrote for Business Week, before becoming business editor at The Boston Globe, in 1980.[17] As a high school student, McKibben wrote for the local paper and participated in statewide debate competitions.[17] Entering Harvard College in 1978, he became an editor of The Harvard Crimson and was chosen president of the paper for the calendar year 1981.[18]

In 1980, following the election of Ronald Reagan, he determined to dedicate his life to the environmental cause.[19]

Graduating in 1982, he worked for five years for The New Yorker as a staff writer, writing much of the Talk of the Town column from 1982 to early 1987. Inspired by the Gospel of Matthew, he became an advocate of nonviolent resistance.[20] While doing a story on the homeless, he lived on the streets; there, he met his wife, Sue Halpern, who was working as a homeless advocate. In 1987, McKibben quit The New Yorker after longtime editor William Shawn was forced out of his job.[19] He and his family shortly after moved to a remote spot in the Southeastern Adirondacks of upstate New York, where he began to work as a freelance writer.[21]

Writing

editMcKibben began his freelance writing career at about the same time that climate change appeared on the public agenda following the hot summer and fires of 1988 and testimony by James Hansen before the United States Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources in June of that year.[22] His first contribution to the debate was a brief list of literature on the subject and commentary published December 1988 in The New York Review of Books and a question, "Is the World Getting Hotter?"[23][24]

He became and remains a frequent contributor to various publications, including The New York Times, The Atlantic, Harper's, Orion, Mother Jones, The American Prospect, The New York Review of Books, Granta, National Geographic, Rolling Stone, Adbusters, and Outside. He is also a board member at and contributor to Grist.

His first book, The End of Nature, was published in 1989 by Random House after being serialized in The New Yorker. Described by Ray Murphy of the Boston Globe as a "righteous jeremiad," the book excited much critical comment, pro and con; was for many people their first introduction to the question of climate change;[25] and the inspiration for a great deal of writing and publishing by others.[26] It has been printed in more than 20 languages. Several editions have come out in the United States, including an updated version published in 2006.

In 1992, The Age of Missing Information was published. It is an account of an experiment in which McKibben collected everything that came across the 100 channels of cable TV on the Fairfax, Virginia, system (at the time among the nation's largest) for a single day. He spent a year watching the 2,400 hours of programming, and then compared it to a day spent on the mountaintop near his home. This book has been widely used in colleges and high schools and was reissued in a new edition in 2006.[27][28]

Subsequent books include Hope, Human and Wild, about Curitiba, Brazil, and Kerala, India, which he cites as examples of people living more lightly on the earth; The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job, and the Scale of Creation, which is about the Book of Job and the environment; Maybe One, about human population; Long Distance: A Year of Living Strenuously, about a year spent training for endurance events at an elite level; and Enough, about what he sees as the existential dangers of genetic engineering and nanotechnology. Speaking about Long Distance at the Cambridge Forum, McKibben cited the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Csikszentmihalyi's idea of "flow" relative to feelings McKibben had had—"taking a break from saving the world", he joked—as he immersed himself in cross-country skiing competitions.[29]

Wandering Home is about a long solo hiking trip from his home in the mountains east of Lake Champlain in Ripton, Vermont, back to his longtime neighborhood of the Adirondacks. His book Deep Economy: the Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future, published in March 2007, was a national bestseller. It addresses what he sees as shortcomings of the growth economy and envisions a transition to more local-scale enterprise.

In fall 2007, he published, with the other members of his Step It Up team, Fight Global Warming Now, a handbook for activists trying to organize their local communities. In 2008, came The Bill McKibben Reader: Pieces from an Active Life, a collection of essays spanning his career. Also in 2008, the Library of America published "American Earth," an anthology of American environmental writing since Thoreau edited by McKibben. In 2010, he published another national bestseller, Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet, an account of the rapid onset of climate change. It was excerpted in Scientific American.[30]

In 2019, McKibben published Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?, which details the growing concerns over climate change, how the Koch Brothers are contributing to an increase in carbon emissions by funding oil companies, and his concern with libertarianism, which he argues was sparked by the politics of the Reagan Revolution. He frequently argues that the Nordic model is preferable to a deregulated capitalist system, and that rapid innovation may come to hurt humanity.

In 2022, he published two books. We Are Better Together is a picture book for children celebrating the power of human cooperation and the beauty of life on Earth, illustrated by artist Stevie Lewis. The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened is a personal memoir that also digs into America's history to reflect on what has brought us to the present environmental crisis.

Some of McKibben's work has been extremely popular;[31][32] an article in Rolling Stone in July 2012 received over 125,000 likes on Facebook, 14,000 tweets, and 5,000 comments.[31][32]

Environmental campaigns

editStep It Up

editStep It Up 2007 was a nationwide environmental campaign started by McKibben to demand action on global warming by the U.S. Congress.

In late summer 2006 he helped lead a five-day walk across Vermont to call for action on global warming. Beginning in January 2007, he founded Step It Up 2007, which organized rallies in hundreds of American cities and towns on April 14, 2007, to demand that Congress enact curbs on carbon emissions by 80 percent by 2050. The campaign quickly won widespread support from a wide variety of environmental, student, and religious groups.

In August 2007 McKibben announced Step It Up 2, to take place November 3, 2007. In addition to the 80% by 2050 slogan from the first campaign, the second adds "10% [reduction of emissions] in three years ("Hit the Ground Running"), a moratorium on new coal-fired power plants, and a Green Jobs Corps to help fix homes and businesses so those targets can be met" (called "Green Jobs Now, and No New Coal").[33]

350.org

editIn the wake of Step It Up's achievements, the same team announced a new campaign in March 2008 called 350.org. The organizing effort, aimed at the entire globe, drew its name from climate scientist James E. Hansen's contention earlier that winter that any atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) above 350 parts per million was unsafe. "If humanity wishes to preserve a planet similar to that on which civilization developed and to which life on Earth is adapted, paleoclimate evidence and ongoing climate change suggest that CO2 will need to be reduced from its current 385 ppm to at most 350 ppm, but likely less than that." Hansen et al. stated in the Abstract to their paper.[34]

350.org, which has offices and organizers in North America, Europe, Asia, Africa and South America, attempted to spread that 350 number in advance of international climate meetings in December 2009 in Copenhagen. It was widely covered in the media.[35] On October 24, 2009, it coordinated more than 5,200 demonstrations in 181 countries, and was widely lauded for its creative use of internet tools, with the website Critical Mass declaring that it was "one of the strongest examples of social media optimization the world has ever seen."[36] Foreign Policy magazine called it "the largest ever global coordinated rally of any kind."[10]

Subsequently, the organization continued its work, with the Global Work Party on 10/10/10 (10 October 2010). As of 2022, McKibben is a senior advisor to 350.0rg and May Boeve is the executive director.[37]

Keystone XL

editMcKibben is one of the environmentalists against the proposed Canadian-U.S. Keystone XL pipeline project.[38]

People's Climate March

editOn May 21, 2014, McKibben published an article on the website of Rolling Stone magazine (later appearing in the magazine's print issue of June 5), titled "A Call to Arms",[39] which invited readers to a major climate march (later dubbed the People's Climate March) in New York City on the weekend of September 20–21, as part of the People's Climate Movement.[note 1] In the article, McKibben calls climate change "the biggest crisis our civilization has ever faced", and predicts that the march will be "the largest demonstration yet of human resolve in the face of climate change".[39]

On Sunday, July 5, 2015, McKibben led a similar climate march in Toronto, Ontario, with the support of various celebrities.[25]

Third Act

editIn September 2021, McKibben launched Third Act, a group and campaign for climate change activists aged 60 or older, hoping to leverage the demographic's free time and accumulated assets for political pressure on government.[40][41] Supporters like Bernie Sanders and Jane Fonda promoted the project.[42]

Electoral politics

editDuring the 2016 Democratic presidential primary campaigns, McKibben served as a political surrogate for Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.[43] Sanders appointed him to the committee charged with writing the Democratic Party's platform for 2016.[44] After Sanders' defeat by Hillary Clinton, McKibben endorsed her and spoke at their first joint event in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.[45] He has been mentioned as a potential future Cabinet member should Sanders win the presidency.[15]

Keynotes

editIn 2020, McKibben delivered a keynote at 2020 Vision: Finding Hope in Climate Action.[46]

Views

editIn 2016, McKibben wrote in The New York Times that he is "under surveillance" by "right-wing stalkers" who photograph, pursue, and inquire about him and members of his family in search of ostensible instances of environmental hypocrisy. "I'm being watched", he reported.[47] Two years later, he wrote in the Times that he had been receiving death threats since the 1990s.[48]

In December 2019, along with 42 other leading cultural figures, McKibben signed a letter endorsing the British Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership in the 2019 general election. The letter stated that "Labour's election manifesto under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership offers a transformative plan that prioritizes the needs of people and the planet over private profit and the vested interests of a few."[49][50]

Personal life

editMcKibben resides in Ripton, Vermont, with his wife, writer Sue Halpern. Their only child, Sophie, was born in 1993 in Glens Falls, New York. He is a Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College, where he also directs the Middlebury Fellowships in Environmental Journalism.[51] McKibben is also a fellow at the Post Carbon Institute. He is a longtime Methodist.[52]

Since 2013, McKibben has been listed on the Advisory Council of the National Center for Science Education.[53]

Awards

edit- McKibben has been awarded both a Guggenheim Fellowship (1993) and a Lyndhurst Fellowship.

- He won a Lannan Literary Award for nonfiction writing in 2000.

- In 2010, Utne Reader magazine listed McKibben as one of the "25 Visionaries Who Are Changing Your World."[54]

- He has honorary degrees from Whittier College (2010),[55] Marlboro College, Colgate University, the State University of New York, Sterling College, Green Mountain College, Unity College, and Lebanon Valley College.

- He won the Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship in 2010, for his work with 350.org[56]

- McKibben was the recipient of the Sierra Club's highest honor in 2011, the John Muir Award.[57]

- In 2012, he won the Sam Rose and Julie Walters Prize for Global Environmental Activism at Dickinson College;[58] accepting the prize, he told the graduating Dickinson students that, in addition to be the greatest problem of their lives, global climate change is the greatest challenge that has ever confronted human society.[59]

- In 2013, he won the international environment and development prize Sophie Prize.

- McKibben and 350.org were awarded the Right Livelihood Award in 2014 for mobilizing growing popular support in the United States and around the world for strong action to counter the threat of global climate change".[14]

- In 2018, McKibben was awarded with the John Steinbeck Award at San Jose State University.[60]

Bibliography

editBooks

edit- McKibben, Bill (1986). The End of Nature. New York: Random House.

- The Age of Missing Information (1992) ISBN 0-394-58933-5, challenges Marshall McLuhan's "global village" ideal and claims the standardization of life in electronic media is that of image and not substance, resulting in a loss of meaningful content in society

- Hope, Human and Wild: True Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth (1995) ISBN 0-316-56064-2

- Maybe One: A Personal and Environmental Argument for Single Child Families (1998) ISBN 0-684-85281-0

- Hundred Dollar Holiday (1998) ISBN 0-684-85595-X

- Long Distance: Testing the Limits of Body and Spirit in a Year of Living Strenuously (2001) ISBN 0-452-28270-5

- Enough: Staying Human in an Engineered Age (2003) ISBN 0-8050-7096-6

- Wandering Home (2005) ISBN 0-609-61073-2

- The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job, and the Scale of Creation (2005) ISBN 1-56101-234-3

- Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future (2007) ISBN 0-8050-7626-3

- Reviewed in Tim Flannery, "We're Living on Corn!" The New York Review of Books 54/11 (28 June 2007) : 26–28

- Fight Global Warming Now: The Handbook for Taking Action in Your Community (2007) ISBN 9780805087048

- The Bill McKibben Reader: Pieces from an Active Life (2008) ISBN 9780805076271

- American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau (edited) (2008) ISBN 9781598530209

- Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet (2010) ISBN 978-0-8050-9056-7

- The Global Warming Reader (OR Books, 2011) ISBN 978-1-935928-36-2

- Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist (Times Books, 2013) ISBN 9780805092844[a]

- Radio Free Vermont: A Fable of Resistance. (Blue Rider Press, 2017) ISBN 9780735219861, 9781524743727

- Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out?. Description & arrow/scrollable preview. (Henry Holt and Co., 2019) ISBN 9781250178268[b]

- We Are Better Together, (Henry Holt and Co., 2022) ISBN 9781250755155[c]

- The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened (Henry Holt and Co., 2022) ISBN 9781250823601[d]

Essays and reporting

edit- McKibben, Bill (January 7, 1985). "An American dilemma". The Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. 60 (47): 21.[e]

- — (January 14, 1985). "Notes and comment". The Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. 60 (48): 23.[f]

- — (January 21, 1985). "Flowers". The Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. 60 (48): 28.[g]

- — (January 28, 1985). "Up front". The Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. 60 (50): 22–23.[h]

- — (October 13, 1986). "Commerce". The Talk of the Town. The New Yorker. 62 (34): 38–39.

- — (June 29, 2015). "Power to the people : why the rise of green energy makes utility companies nervous". Annals of Innovation. The New Yorker. 91 (18): 30–35.[i]

- — (August 15, 2016). "A World at War". The New Republic.

- — (March 18, 2022). "In A World on Fire, Stop Burning Things". The New Yorker.

- "Toward a Land of Buses and Bikes" (review of Ben Goldfarb, Crossings: How Road Ecology Is Shaping the Future of Our Planet, Norton, 2023, 370 pp.; and Henry Grabar, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World, Penguin Press, 2023, 346 pp.), The New York Review of Books, vol. LXX, no. 15 (5 October 2023), pp. 30–32. "Someday in the not impossibly distant future, if we manage to prevent a global warming catastrophe, you could imagine a post-auto world where bikes and buses and trains are ever more important, as seems to be happening in Europe at the moment." (p. 32.)

———————

- Notes

- ^ "Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist, by Bill McKibben". billmckibben.com.

- ^ Davies, Dave (April 16, 2019). "Climate Change Is 'Greatest Challenge Humans Have Ever Faced,' Author Says". Fresh Air - NPR.org. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (April 5, 2022). We Are Better Together. Henry Holt and Company (BYR). ISBN 978-1-250-75515-5.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (May 31, 2022). The Flag, the Cross, and the Station Wagon: A Graying American Looks Back at His Suburban Boyhood and Wonders What the Hell Happened. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-250-82360-1.

- ^ Renaming of Sixth Avenue in Manhattan as 'Avenue of the Americas'.

- ^ Friend whose prior military rank was inadvertently promoted by Geraldine Ferraro.

- ^ Textile designers Leslie Tillett and Brian Goodin.

- ^ Rolls-Royce grille designer Tony Kent.

- ^ Title in the online table of contents is "Solar power for everyone".

Filmography

editBroadcasts

edit- McKibben, Bill (June 18, 2010). "Point of Inquiry - Our Strange New Eaarth". Point of Inquiry. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- McKibben, Bill (March 24, 2012). "The rise of public radio in the US". Saturday Extra. Australia: ABC Radio National. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- McKibben, Bill (September 17, 2014). "People's Climate March with Rev. Yearwood". United States: Blog Talk Radio. Retrieved September 23, 2014.[permanent dead link]

Documentary film

edit- Do The Math (2013), 42-minute documentary (written and directed by Kelly Nyks and Jared Scott) on fossil fuel phase-out and fossil fuel divestment, featuring him[61][62]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ Both dates were mentioned in the article because the actual date of the march was uncertain at the time of publication. After negotiations with New York City authorities, event planners chose Sunday, September 21 as the date.

Citations

edit- ^ a b "Bill Ernest McKibben." Environmental Encyclopedia. Edited by Deirdre S. Blanchfield. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 2009. Retrieved via Biography in Context database, December 31, 2017.

- ^ "Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben appointed Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College | Middlebury". Middlebury.edu. November 9, 2010. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (2019). Falter: Has the Human Game Begun to Play Itself Out? Description & arrow/scrollable preview. Henry Holt and Co. Retrieved 2022-03-07.

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. (October 10, 2010). "A Global Warming 'Work Party'". The New York Times. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Global Work Party: 10/10/10 day of climate action". The Guardian. theguardian.com. October 11, 2010. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Revkin, Andrew C. (November 23, 2010). "Art on the Scale of the Climate Challenge". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 12, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ Moran, Barbara (January 22, 2012). "The man who crushed the Keystone XL pipeline". The Boston Globe. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Remsen, Remsen (August 23, 2011). "McKibben out of jail; encourages more protests". Burlington Free Press. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ "Bill McKibben 2013 Gandhi Peace Award Laureate". Promoting Enduring Peace. pepeace.org. April 18, 2013. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- ^ a b "The FP Top 100 Global Thinkers". Foreign Policy. December 2009. Archived from the original on December 3, 2009. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "MSN Lifestyle's Most Influential Men of 2009". MSN. Archived from the original on December 16, 2009. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ Shivani, Anis (May 30, 2010). "Facing cold, hard truths about global warming". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (April 26, 2010). "The Skimmer". Time. Archived from the original on April 23, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ a b "Bill McKibben / 350.org (USA)". Right Livelihood. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Smith, Aidan (April 10, 2019). "What Would A Left Cabinet Look Like?". Current Affairs. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Bill McKibben". Library.thinkquest.org. Archived from the original on April 4, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c Nisbet, Matthew C. (March 2013). "Nature's Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series #D-78. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, School of Communication and the Center for Social Media, American University. p. 25. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ Flow, Christian B. (June 4, 2007). "William E. McKibben". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Matthew C. (March 2013). "Nature's Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series #D-78. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, School of Communication and the Center for Social Media, American University. p. 26. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "Time We Started Counting!" (PDF). High Profiles. June 2, 2016. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- ^ Terrie, Philip (May 2008). "The Bill McKibben Reader". Adirondack Explorer. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ Shabecoff, Philip (June 24, 1988). "Global Warming Has Begun, Expert Tells Senate". The New York Times. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

... Dr. James E. Hansen of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration told a Congressional committee that it was 99 percent certain that the warming trend was not a natural variation but was caused by a buildup of carbon dioxide and other artificial gases in the atmosphere.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (December 8, 1988). "Is the World Getting Hotter?". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved March 9, 2013.

- ^ Nisbet, Matthew C. (March 2013). "Nature's Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series #D-78. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, School of Communication and the Center for Social Media, American University. pp. 27–28. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Aulakh, Raveena (July 5, 2015). "Gentle climate warrior turns up the heat". Toronto Star.

- ^ Nisbet, Matthew C. (March 2013). "Nature's Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series #D-78. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, School of Communication and the Center for Social Media, American University. pp. 30–33. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "The Age of Missing Information". Entertainment. ew.com. May 1, 1992. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ Huth, Tom (May 3, 1992). "Being There: The Age of Missing Information, by Bill McKibben". Los Angeles Times. latimes.com. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Cambridge Forum" Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, via Maine Public Broadcasting Network (radio), September 14, 2011 12:30 pm. No transcript, audio archive or original recording date; cambridgeforum.org non-responsive. Information off the air 2011-09-14.

- ^ "Living On a New Earth". Scientific American (preview only; subscription required). April 21, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ a b McKibben, Bill (July 19, 2012). "Global Warming's Terrifying New Math: Three simple numbers that add up to global catastrophe - and that make clear who the real enemy is". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Nisbet, Matthew C. (March 2013). "Nature's Prophet: Bill McKibben as Journalist, Public Intellectual and Activist" (PDF). Discussion Paper Series #D-78. Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy, School of Communication and the Center for Social Media American University. p. 17. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ^ "Step It Up : Index". www.stepitup2007.org.

- ^ Hansen, J., Mki. Sato, P. Kharecha, D. Beerling, R. Berner, V. Masson-Delmotte, M. Pagani, M. Raymo, D.L. Royer, and J.C. Zachos, 2008: Target atmospheric CO2: Where should humanity aim? Open Atmospheric Science Journal, 2, 217-231, doi:10.2174/1874282300802010217. [1]

- ^ Rosenthal, Elisabeth (March 1, 2009). "Obama's Backing Raises Hopes for Climate Pact". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2010.

- ^ "350.org | experience matters". Experiencematters.criticalmass.com. October 30, 2009. Archived from the original on April 23, 2011. Retrieved May 9, 2011.

- ^ "Meet the 350.org Team". 350.

- ^ Más presión de Keystone a Vía Verde. (English: Greater pressure from Keystone on Vía Verde.) La Perla del Sur. Ponce, Puerto Rico. Published January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ a b McKibben, Bill (May 21, 2014). "A Call to Arms: An Invitation to Demand Action on Climate Change". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 28, 2014.

- ^ Cotton, Emma (September 2, 2021). "Bill McKibben launches 'Third Act' to rally older Americans around climate change". VTDigger. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Avenue, Next (November 5, 2021). "How Environmentalist Bill McKibben Is Leading The 'Third Act' Climate Change Movement". Forbes. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Corbett, Jessica (September 2, 2021). "Older Adults in Their 'Third Act' Launch New Effort to Save the Planet". www.commondreams.org. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Merica, Dan (January 20, 2016). "For messages Clinton can't deliver, campaign taps surrogates". CNN. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ Gearan`, Anne (May 23, 2016). "Sanders wins greater say in Democratic platform; names pro-Palestinian activist". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ^ Wagner, John (July 12, 2016). "Sanders pledges to support Clinton". The Washington Post. The rally began with two Sanders supporters speaking: him and Jim Dean, the leader of Democracy for America, a grassroots group that endorsed Sanders in the primaries....“Secretary Clinton, we wish you Godspeed in the fight that now looms,” McKibben said.

- ^ "Climate justice activist to keynote CEBE convergence". Lewiston Sun Journal. March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (August 5, 2016). "Opinion | Embarrassing Photos of Me, Thanks to My Right-Wing Stalkers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 30, 2018.

- ^ McKibben, Bill (October 20, 2018). "Let's Agree Not to Kill One Another". Opinion. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ "Vote for hope and a decent future". The Guardian. December 3, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ Proctor, Kate (December 3, 2019). "Coogan and Klein lead cultural figures backing Corbyn and Labour". The Guardian. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- ^ "Author and environmentalist Bill McKibben appointed Schumann Distinguished Scholar at Middlebury College". middlebury.edu. November 8, 2010.

- ^ "Q&A:Bill McKibben, UM writer/activist". United Methodist Portal. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- ^ "Advisory Council". ncse.com. National Center for Science Education. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ "Bill McKibben: Voice of Reason, Man of Action". Utne Reader. October 13, 2010. Retrieved October 19, 2010.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees | Whittier College". www.whittier.edu. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ Cecile Richards and Bill McKibben Announced as Recipients of the 2010 Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship, Common Dreams NewsCenter November 9, 2010.

- ^ "Volunteer Award Winners". Sierra Club. January 28, 2015. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ Getty, Matt. "The Sam Rose '58 and Julie Walters Prize at Dickinson College for Global Environmental Activism". www.dickinson.edu.

- ^ Pohlman, Pat. "350.org Founder Bill McKibben Accepts Inaugural Environmental Prize". www.dickinson.edu.

- ^ "Bill McKIbben". The John Steinbeck Award. Retrieved September 14, 2023.

- ^ The Do the Math movie, 350.org (page visited on November 13, 2016).

- ^ Do the Math (2013) at IMDb (page visited on November 13, 2016).

External links

edit- Official website

- Articles by Bill McKibben at The New Yorker

- Bill McKibben at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Review of 'Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet' Archived November 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at Mother Nature Network

- Keystone: How Bill McKibben Turned a Pipeline into an Environmental Rallying Point March 5, 2012

- Bill McKibben's Battle Against the Keystone XL Pipeline February 28, 2013 BusinessWeek

- "The Singularity", a documentary film featuring McKibben

- “Focus; The End of Nature,” 1989-11-29, WILL Illinois Public Media, American Archive of Public Broadcasting (GBH and the Library of Congress), Boston, MA and Washington, DC.