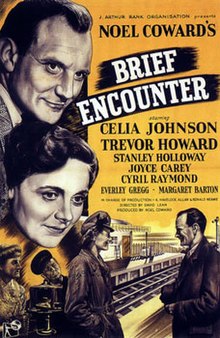

Brief Encounter is a 1945 British romantic drama film directed by David Lean from a screenplay by Noël Coward, based on his 1936 one-act play Still Life. The film stars Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard in lead roles, alongside Stanley Holloway, Joyce Carey, Cyril Raymond, Everley Gregg and Margaret Barton in supporting roles.

| Brief Encounter | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | David Lean |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Still Life 1936 play by Noël Coward |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Robert Krasker |

| Edited by | Jack Harris |

| Music by | Sergei Rachmaninoff |

| Distributed by | Eagle-Lion Distributors |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 87 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[2] or $1.4 million[3] |

Brief Encounter tells the story of two married strangers living in pre-World War II England, whose chance meeting at a railway station leads to a brief yet intense emotional affair, disrupting their otherwise conventional lives.

Brief Encounter premiered in London on 13 November 1945, followed by its wide release on 25 November. The film received widespread critical acclaim, with Johnson and Howard's performances earning high praise. However, despite critical acclaim, it emerged as a moderate commercial success at the box-office.

At the 19th Academy Awards, Brief Encounter received 3 nominations – Best Director (Lean), Best Actress (Johnson) and Best Adapted Screenplay. but failed to win in any category. However, the film won the Palme d'Or at the 1st Cannes Film Festival, while Johnson won the New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Actress.

Many critics, historians, and scholars consider Brief Encounter as one of the greatest films of all time. In 1999, the British Film Institute ranked it the second-greatest British film of all time. In 2017, a Time Out poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers, and critics ranked it the 12th-best British film ever.[4]

Plot

editIn a railway station refreshment room, a man and a woman are sitting glumly at a table when one of the woman's friends comes in and immediately begins chatting away. After some terse pleasantries, the man leaves to catch his train. The man's companion explains that the man is about to move to Africa. After the man leaves, the companion briefly disappears without warning but returns, explaining that she wanted to see the express train. After a short interval, the two women head for their own train.

At home, Laura Jesson, the woman at the table, sits in the living room with her husband Fred. Although Fred is a kind man, he lacks Laura's ear for music and seems more interested in filling out the crossword than conversing with his wife. Laura silently reflects on her recent experiences, which she retells in the form of a confession to her husband.

Like many women of her social standing at the time, Laura visits a nearby town every week to shop and watch a matinée film. During one such outing to Milford, while waiting in the railway station's refreshment room, she is assisted by a fellow passenger, Alec Harvey, who removes a piece of grit from her eye. Alec is an idealistic general practitioner who also works as a consultant at the local hospital on Thursdays. Both Laura and Alec are married with children, although Alec's wife Madeleine and their two sons are never seen.

The two encounter each other again by chance the following week outside Boots the Chemist, and during a third meeting, they share a table at lunch. With time to spare, they attend an afternoon performance at the Palladium Cinema. They soon become uneasy as their innocent, casual relationship begins to deepen, verging on infidelity. They eventually admit they love each other.

Laura and Alec continue meeting in public until they unexpectedly run into some of Laura's friends, necessitating the first of many deceptions. Eventually, they agree to make love at the flat of Alec's friend Stephen, who has dinner plans. However, Stephen returns unexpectedly. Stephen overhears Laura sneaking out and subtly chides Alec for his infidelity. A distraught Laura wanders the streets for three hours until a concerned police officer urges her to go home.

Alec surprises Laura at the train station. They admit to each other that it is impossible for them to maintain their relationship. Alec reveals that he has been offered a job in Johannesburg, South Africa, where his brother lives. Although he was initially unsure whether to take it, he decides he must leave England to put a definitive end to his affair with Laura, and to avoid hurting their families. He offers to leave the decision to Laura, but Laura replies, "That's unkind of you, my darling."

The next week, Laura and Alec have their final meeting in the railway station refreshment room, now seen with the poignant perspective of their shared history. As they prepare to part for the last time, Dolly Messiter, an acquaintance of Laura's, interrupts them, oblivious to their anguish.

Alec’s train arrives before they can say a proper goodbye. He discreetly squeezes Laura’s shoulder as he departs, leaving her with Dolly. Laura, overcome with emotion, nearly commits suicide by jumping in front of an express train. However, she gathers herself and returns home to her family.

At home, Laura is nearly overcome with emotion. Fred senses her turmoil and acknowledges Laura's emotional distance, though whether he understands the cause remains unclear. He thanks her for coming back to him, and she weeps in his arms.

A parallel subplot involves the interactions of the station and refreshment room staff. Two of the staff flirt with each other but cannot engage in public displays of affection during work hours, which humorously contrasts with Laura and Alec's ability to meet openly with each other and inability to have a relationship outside of work hours.

Cast

edit- Celia Johnson as Laura Jesson

- Trevor Howard as Dr Alec Harvey

- Stanley Holloway as Albert Godby, the ticket inspector

- Joyce Carey as Myrtle Bagot, the cafe owner

- Cyril Raymond as Fred Jesson

- Everley Gregg as Dolly Messiter

- Margaret Barton as Beryl Walters, tea-room assistant

- Marjorie Mars as Mary Norton

- Alfie Bass (uncredited) as the waiter at the Royal

- Wallace Bosco (uncredited) as the doctor at Bobbie's accident

- Sydney Bromley (uncredited) as Johnnie, second soldier

- Noël Coward (uncredited) as the railway station announcer

- Nuna Davey (uncredited) as Hermionie Rolandson, Mary's cousin

- Valentine Dyall (uncredited) as Stephen Lynn, Alec's friend

- Irene Handl (uncredited) as cellist and organist

- Richard Thomas (uncredited) as Bobby Jesson, Fred and Laura's son

- Henrietta Vincent (uncredited) as Margaret Jesson, Fred and Laura's daughter

Adaptation

editStill Life

editBrief Encounter is based on Noël Coward's one-act play Still Life (1936), one of ten short plays in the cycle Tonight at 8.30, designed for Gertrude Lawrence and Coward himself, to be performed in various combinations as triple bills. All scenes in Still Life are set in the refreshment room of a railway station, the fictional Milford Junction.

As is common in films adapted from stage plays, the film includes settings that are only mentioned in the play, such as Dr. Lynn's flat, Laura's home, a cinema, a restaurant, and a branch of Boots the Chemist. Several scenes were added for the film, including a scene on a lake where Dr. Harvey gets his feet wet, Laura wandering alone in the dark and smoking on a park bench where she is confronted by a police officer, and a drive in the country in a hired car.

Some scenes were altered to be less ambiguous and more dramatic in the film adaptation. The scene in which the lovers are about to commit adultery is toned down; in the play, it is left to the audience to decide whether they actually consummate their relationship, while in the film, it is implied that they do not. In the film, Laura has only just arrived at Dr. Lynn's flat when the owner returns, prompting Dr. Harvey to quickly escort her out via the kitchen service door. Additionally, when Laura contemplates suicide by throwing herself in front of a train, the film makes her intention clearer through voice-over narration.

In the play, the characters at Milford station—Mrs. Bagot, Mr. Godby, Beryl, and Stanley—are aware of the growing relationship between Laura and Alec and occasionally mention it in an offhand manner. In the film, these characters pay little attention to the couple. The film's final scene, where Laura embraces her husband after he acknowledges her emotional distance and possibly suspects the cause, is not present in the original play.

Two editions of Coward's original screenplay for the film adaptation are available, both listed in the bibliography.

Production

editMuch of the film was shot at Carnforth railway station in Lancashire, then a junction on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway. Although it was a busy station, it was far enough away from major cities to avoid the blackout for film purposes, allowing shooting to take place in early 1945 before World War II had ended. At two points in the film, platform signs indicate local destinations such as Leeds, Bradford, Morecambe and Lancaster, even though Milford is intended to be in the Home Counties. Noël Coward provided the station announcements in the film. The station refreshment room was recreated in a studio. Carnforth Station retains many of the period features from the time of filming and has become a place of pilgrimage for fans of the film.[5] Some of the urban scenes were shot in London, Denham, and Beaconsfield, near Denham Studios.[6]

The country bridge the lovers visit twice, including on their final day, is Middle Fell Bridge at Dungeon Ghyll in Cumbria.[7]

The poem that Fred asks Laura to help him with for his crossword is by John Keats: "When I have Fears that I may Cease to Be". The quote Fred recites is "When I behold, upon the night's starr'd face, huge cloudy symbols of a high romance".

In addition to the Keats reference, there is a visual reference to an Arabic love poem.[8] In Dr. Lynn's apartment, a wall hanging is prominently displayed twice—first over the dining table when Laura enters, and later over Alec's left shoulder when Stephen confronts him.

The original choice for the role of Alec Harvey was Roger Livesey, but David Lean cast Trevor Howard after seeing him in The Way to the Stars.[9] Joyce Barbour was originally cast as Dolly, but Lean was dissatisfied with her performance, and she was replaced by Everley Gregg.[10]

Music

editExcerpts from Sergei Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto No. 2 recur throughout the film, performed by the National Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Muir Mathieson, with Eileen Joyce as the pianist.[11] Additionally, there is a scene in a tearoom where a salon orchestra plays Spanish Dance No. 5 (Bolero) by Moritz Moszkowski.

Release

editBox office

editAccording to trade papers, Brief Encounter was a "notable box-office attraction" and was the 21st most popular film at the British box office in 1946.[12][13] Kinematograph Weekly reported that the biggest box office success in Britain that year was The Wicked Lady, with other major hits including The Bells of St Mary's, Piccadilly Incident, The Road to Utopia, Tomorrow Is Forever, Brief Encounter, Wonder Man, Anchors Aweigh, Kitty, The Captive Heart, The Corn Is Green, Spanish Main, Leave Her to Heaven, Gilda, Caravan, Mildred Pierce, Blue Dahlia, Years Between, O.S.S., Spellbound, Courage of Lassie, My Reputation, London Town, Caesar and Cleopatra, Meet the Navy, Men of Two Worlds, Theirs Is the Glory, The Overlanders, and Bedelia.[14]

Critical reception

editBrief Encounter received widespread critical acclaim, with Johnson and Howard's performances earning high praise;[15] although there were doubts that it would be "generally popular".[16] Variety praised the film, stating, "Coward's name and strong story spell nice US chances."[17]

It was a moderate success in the UK and became a major hit in the US, leading to Johnson's nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress.

Today, Brief Encounter is widely acclaimed for its black-and-white cinematography and the evocative atmosphere created by its steam-age railway setting, elements particularly associated with David Lean's original version.[18] On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 91% based on 46 reviews, with an average rating of 8.6/10. The site's critical consensus states: "Brief Encounter adds a small but valuable gem to the Lean filmography, depicting a doomed couple's illicit connection with affecting sensitivity and a pair of powerful performances."[19][20] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 92 out of 100, based on 16 critics, indicating "universal acclaim."[21]

Awards and nominations

edit| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Director | David Lean | Nominated | [22] |

| Best Actress | Celia Johnson | Nominated | ||

| Best Screenplay | Anthony Havelock-Allan, David Lean, and Ronald Neame | Nominated | ||

| Cannes Film Festival | Palme d'Or | Won | [23] | |

| National Board of Review Awards | Top Ten Films | 4th Place | [24] | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Actress | Celia Johnson | Won | [25] |

Legacy

editIn her book Noël Coward (1987), Frances Gray notes that Brief Encounter is, after Coward’s major comedies, the one work of his that almost everybody knows and has likely seen. The film has frequently aired on television to high viewership consistently.

Its story is that of an unconsummated affair between two married people [....] Coward is keeping his lovers in check because he cannot handle the energies of a less inhibited love in a setting shorn of the wit and exotic flavour of his best comedies [....] To look at the script, shorn of David Lean's beautiful camera work, deprived of an audience who would automatically approve of the final sacrifice, is to find oneself asking awkward questions (pp. 64–67).

Brief Encounter has earned a lasting legacy in cinema history. In 1952, it was voted one of the 10 greatest films ever made in two separate critics' polls.[26] In 1999, the British Film Institute ranked it #2 on the BFI Top 100 British films list, and in 2004, Total Film magazine named it the 44th greatest British film of all time. Film critic Derek Malcolm included it in his 2000 column The Century of Films. British historian Thomas Dixon remarked that Brief Encounter "has become a classic example of a very modern and very British phenomenon—weeping over the stiff upper lip, crying at people not crying. The audiences for these wartime weepies could, through their own tears, provide something that was lacking in their own lives as well as those of the on-screen stoics they admired."[27]

Director Robert Altman's wife Kathryn Altman said, "One day, years and years ago, just after the war, [Altman] had nothing to do and he went to a theater in the middle of the afternoon to see a movie. Not a Hollywood movie: a British movie. He said the main character was not glamorous, not a babe. And at first he wondered why he was even watching it. But twenty minutes later, he was in tears, and had fallen in love with her. And it made him feel that it wasn't just a movie." The film was Brief Encounter.[28]

The film's influence extends into other works. The British play and film The History Boys features two characters reciting a passage from Brief Encounter.

The episode "Grief Encounter" of the British comedy series Goodnight Sweetheart features a reference to Coward and includes a scene filmed at Milford railway station, echoing Brief Encounter. Similarly, Mum's Army, an episode of Dad's Army appears to be loosely inspired by the film.

Brief Encounter also serves as a plot device in Mrs. Palfrey at the Claremont (2005), a comedy-drama film based on Elizabeth Taylor's 1971 novel. In the story, the aging widow Mrs. Palfrey reminisces about Brief Encounter as her and her late husband’s favorite film, leading to a significant connection between her young friend and writer Ludovic Meyer and his eventual girlfriend.

In the 2012 Sight & Sound polls of the world’s greatest films, Brief Encounter received votes from 11 critics and three directors.[29]

Social context

editThis section's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (March 2017) |

Frances Gray acknowledges a common criticism of the play: why do the characters not consummate the affair? Gray argues that the characters' restraint is rooted in class consciousness. While the working classes might be seen as vulgar and the upper classes as frivolous, the middle class, which sees itself as the moral backbone of society, upholds these values. Coward, whose principal audience was the middle class, was reluctant to question or jeopardize these norms.[30]

In her narration, Laura emphasizes that what ultimately holds her back is not class consciousness, but her deep-seated horror at the thought of betraying her husband and her moral principles, despite being profoundly tempted by her emotions. This tension between desire and duty is a key element that has contributed to the film's enduring appeal.

The values that Laura precariously, but ultimately successfully, upholds were widely shared and respected at the time of the film's setting. For instance, the stigma associated with divorce was significant enough to cause Edward VIII to abdicate in 1936. Updating the story to a more contemporary setting might have rendered these values obsolete, thereby undermining the plot's credibility—a factor that may explain why the 1974 remake failed to resonate as strongly.[31]

The film was released against the backdrop of the Second World War, a period when "brief encounters" were common, and women experienced greater sexual and economic freedom than before. In British National Cinema (1997), Sarah Street argues that "Brief Encounter articulated a range of feelings about infidelity that invited easy identification, whether it involved one's husband, lover, children, or country (p. 55). In this context, feminist critics have interpreted the film as an attempt to stabilize relationships and restore the pre-war social order.[32]

In his 1993 BFI book on the film, Richard Dyer notes that, with the rise of homosexual law reform, gay men also identified with the characters' plight, seeing it as analogous to their own social constraints in forming and maintaining relationships. Sean O'Connor further considers the film an "allegorical representation of forbidden love," informed by Coward's experiences as a closeted gay man.[33]

Further adaptations

editRadio

editBrief Encounter was adapted as a radio play on the 20 November 1946 episode of Academy Award Theater, starring Greer Garson.[34] It was also presented three times on The Screen Guild Theater: on 12 May 1947 with Herbert Marshall and Lilli Palmer, on 12 January 1948 with Marshall and Irene Dunne, and on 11 January 1951 with Stewart Granger and Deborah Kerr. Additionally, Lux Radio Theater adapted the film on 29 November 1948 with Garson and Van Heflin, and again on 14 May 1951 with Olivia de Havilland and Richard Basehart.

On 30 October 2009, as part of the celebrations for the 75th anniversary of the BBC's Maida Vale Studios, Jenny Seagrove and Nigel Havers starred in a special Radio 2 production of Brief Encounter, performed live from Maida Vale's studio 6 (MV6). The script used was a 1947 adaptation for radio by Maurice Horspool, which had been in the BBC's archives and had never been performed since its creation.

In addition, Theatre Guild on the Air broadcast two adaptations of Brief Encounter in its original form, Still Life. The first aired on 6 April 1947 on ABC featuring Ingrid Bergman, Sam Wanamaker and Peggy Wood. The second aired on 13 November 1949 on NBC, starring Helen Hayes and David Niven.

TV

edit- In 1961, Brief Encounter was adapted for television, starring Dinah Shore and Ralph Bellamy.[35]

- A 1974 television remake, aired in the United States on Hallmark Hall of Fame, featured Sophia Loren and Richard Burton. However, this version was not well received by critics or audiences.[36]

Theatre

editThe first adaptation of Brief Encounter to source from both the screenplay and Noël Coward's original stage material was created by Andrew Taylor and starred Hayley Mills. This production embarked on its first national tour in 1996 and later transferred to the West End, where it played at the Lyric Theatre, Shaftesbury Avenue, in 2000, featuring Jenny Seagrove in the lead role.

Emma Rice/Kneehigh Theatre adaptation

The Kneehigh Theatre production, adapted and directed by Emma Rice, was a unique blend of the film and Coward's original stage play, incorporating additional musical elements. Produced by David Pugh and Dafydd Rogers, the adaptation premiered at Birmingham Repertory Theatre in October 2007 and later at the West Yorkshire Playhouse before opening in February 2008 at the Haymarket Cinema in London, which was temporarily converted into a theatre for the play.[37][38] The 2008 London cast included Amanda Lawrence, Tamzin Griffin, Tristan Sturrock, and Naomi Frederick in lead roles. The production ran until November 2008 and subsequently toured the UK from February to July 2009, with performances at venues including the Oxford Playhouse, Marlowe Theatre and Richmond Theatre. During the tour, the lead roles were played by Hannah Yelland and Milo Twomey.

The US premiere of the Kneehigh adaptation was held at the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco from September to October 2009.[39] The production later moved to St. Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn, New York, for performances in December 2009 and January 2010, followed by a run at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis from February to April 2010.[40]

A Roundabout Theatre Company production of the Kneehigh adaptation opened at Studio 54 in New York City on 28 September 2010, starring Hannah Yelland, Tristan Sturrock, and other members of the London cast.[41] The limited engagement closed on 2 January 2011, after 21 previews and 119 performances, including a four-week extension.[42]

After an Australian tour in the autumn of 2013, Kneehigh's Brief Encounter was staged at the Wallis Annenberg Center in Beverly Hills and the Shakespeare Theatre in Washington, D.C., in the spring of 2014.[43]

The production returned to the UK in 2018, opening at Birmingham Repertory Theatre (where it originally premiered) and The Lowry in Salford in February, before returning to the Haymarket Cinema in London from March to September 2018.

Opera

editIn May 2009, Houston Grand Opera premiered a two-act opera titled Brief Encounter, based on the film's story. The opera featured music by André Previn and a libretto by John Caird.[44][45]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Brief Encounter". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "US Life or Death to Brit Pix". Variety. 25 December 1946. p. 9. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "London West End Has Big Pix Sked". Variety. 21 November 1945. p. 19. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- ^ Huddleston, Tom. "The 100 best British films". Time Out. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "Cumbria on Film – Brief Encounter (1945)". BBC. 28 October 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Whitaker, Brian (1990). Notes & Queries. Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-872180-22-1.

- ^ "Brief Encounter, Middle Fell Bridge, Dungeon Ghyll, Cumbria, UK". Waymarking.com. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "طلال مداح - لسان الهوى". Youtube.com. Retrieved 9 November 2024.

- ^ Brownlow p 195

- ^ Brownlow p 198

- ^ Reid, John Howard (2012). 140 All-Time Must-See Movies for Film Lovers. Lulu. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-10575-295-7. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ Murphy, Robert (2003). Realism and Tinsel: Cinema and Society in Britain 1939–48. London, UK: Routledge. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-41502-982-7.

- ^ "Hollywood Sneaks in 15 Films on '25 Best' List of Arty Britain". The Washington Post. 15 January 1947. p. 2.

- ^ Lant, Antonia (1991). Blackout: Reinventing Women for Wartime British Cinema. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-69100-828-8.

- ^ Turner, Adrian (26 June 2000). "Brief Encounter". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

On its initial release, Brief Encounter was hailed as a groundbreaking piece of realism [...]

- ^ Lejeune, C. A. (25 November 1945). "Brief Encounter". The Observer. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- ^ "Brief Encounter". Variety. 28 November 1945. p. 17.

- ^ Huntley, John (1993). Railways on the Screen. Shepperton: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-2059-0.

- ^ "Brief Encounter (1945)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Brief Encounter". Rotten Tomatoes. 26 November 1945. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ "Brief Encounter Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ^ "The 19th Academy Awards (1947) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Awards 1946: Competition". Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016.

- ^ "1946 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1946 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Brief Encounter (1945)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Dixon, Thomas (2015). Weeping Britannia: Portrait of a Nation in Tears. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-967605-7.

- ^ A quote from the final scene in the 2014 documentary Altman.

- ^ "Votes for Brief Encounter (1946)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ^ Gray, Frances (1987). Noel Coward. Macmillan Modern Dramatists. London, UK: Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 1-3491-8802-6.

- ^ Handford, Peter (1980). Sounds of Railways. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7631-4.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (26 August 1946). "THE SCREEN IN REVIEW". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- ^ O'Connor (1998), p. 157.

- ^ "Greer Garson Stars in "Brief Encounter" On Academy Award—WHP". Harrisburg Telegraph. 16 November 1946. p. 17. Retrieved 14 September 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Review of production at Variety

- ^ O'Connor, John J. (12 November 1974). "TV - 'Brief Encounter' - Burton and Miss Loren Portray Lovers on Hallmark Film at 8.30 on NBC". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- ^ Billington, Michael (18 February 2008). "Theatre Review: Brief Encounter". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ^ Cheal, David (8 February 2008). "Brief Encounter: 'I want people to laugh and cry. That's our job'". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ "Noel Coward's 'Brief Encounter'". American Conservatory Theater. Archived from the original on 6 October 2009.

- ^ "Current shows & projects". Kneehigh Theatre. 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2009.

- ^ Diamond, Robert (7 June 2010). "Noel Coward's 'Brief Encounter' to Open at Studio 54 in September". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (2 January 2011). "Broadway's 'Brief Encounter', a Romance With Theatrical Lift, Ends Jan. 2". Playbill. Archived from the original on 14 January 2011.

- ^ "Tour Dates". Kneehigh Theatre. 2013. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Brief Encounter - Previn - World Premiere". Houston Grand Opera. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009.

- ^ Walker, Lynne (24 October 2008). "Brief Encounter: The Opera". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- ^ "Row over Kerala State Films Award - Times of India". The Times of India.

Sources

edit- Brownlow, Kevin (1997). David Lean : a biography. A Wyatt Book for St. Martin's Press.

- Vermilye, Jerry (1978). The Great British Films. Citadel Press. pp. 91–93. ISBN 0-8065-0661-X.

- Coward, Noël (1999). Brief Encounter: Screenplay. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19680-2.

- Dyer, Richard (1993). Brief Encounter. London, UK: British Film Institute. ISBN 978-0-85170-362-6.

- O'Connor, Sean (1998). Straight Acting: Popular Gay Drama from Wilde to Rattigan. London, UK: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-32866-9.

- Street, Sarah (1997). British National Cinema. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06736-7.

External links

edit- Brief Encounter at IMDb

- Brief Encounter at the TCM Movie Database

- Brief Encounter at AllMovie

- Brief Encounter at Rotten Tomatoes

- Brief Encounter at the BFI's Screenonline. Full synopsis and film stills (and clips viewable from UK libraries)

- Ireland, Alison (November 2004). "'Still Life' at the Burton Taylor". BBC Oxford.

- "Brief Encounter: movie review". Leninimports. 2014. Archived from the original on 12 May 2018.

- "Locations: Brief Encounter". Britmovie. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010.

- Turner, Adrian (26 June 2000). "Brief Encounter". Criterion Collection.

- Brownlow, Kevin (27 March 2012). "'Riskiest Thing I Ever Did': Notes on Brief Encounter". Criterion Collection.

Streaming audio

- "Brief Encounter". Academy Award Theater. 20 November 1946.

- "Brief Encounter". Screen Guild Theater. 12 May 1947.

- "Brief Encounter". Screen Guild Theater. 26 January 1948.