The Caroline affair (also known as the Caroline case) was an international incident involving the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Canadas which started in 1837 and lasted until 1842. While ultimately a minor historical event, it eventually acquired substantial international legal significance.[1][2]

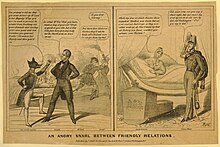

The affair began on December 28, 1837, when hundreds of Americans who had been recruited by Upper Canada Rebellion leader William Lyon Mackenzie encamped on Navy Island on the Canadian side of the Niagara River. They had been brought there by the small American steamer Caroline, which had made several trips that day between Navy Island and Schlosser, New York. Late that night, a British force crossed the Niagara River to board and capture the vessel where it was moored at Schlosser's Landing in U.S. territory. Shots were exchanged and an American watchmaker was killed, before the force set fire to Caroline and set it adrift in the Niagara River, about two miles (3.2 km) above Niagara Falls. Sensationalized accounts of the affair were published by newspapers.[3]

The burning was praised in Canada and condemned in the United States. In retaliation, a group of thirteen Americans destroyed a British steamer in American waters, and U.S. citizens demanded their government declare war on Britain. The diplomatic crisis was defused during the negotiations of several US–UK disputes that led to the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1842. In the course of these negotiations, both the United States and Britain made concessions concerning their conduct. The incident was used to establish the principle of "anticipatory self-defense" in international relations, which holds that it may be justified only in cases in which the "necessity of that self-defense is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation". This formulation is part of the Caroline test.[4]

Background

editThe Reform Movement of Upper Canada in Ontario was a movement to make the British colonial administration in Canada more democratic and less corrupt. William Lyon Mackenzie was one of the key leaders of this movement. He was repeatedly elected to serve in a hostile parliament that repeatedly ejected him for his reform efforts. By 1837, Mackenzie had given up on peaceful means for reform and began to prepare for an uprising.[citation needed]

In December 1837, Mackenzie began the Upper Canada Rebellion by fighting government troops in the Battle of Montgomery's Tavern. His forces were heavily outnumbered and outgunned, and they were defeated in less than an hour. Mackenzie's allies suffered another major setback a few days later in London. After these defeats, Mackenzie and his followers fled to Navy Island in the Niagara River, which they declared the foundation of the Republic of Canada on board the vessel Caroline. Throughout these events, the Canadian rebels enjoyed widespread support from American citizens, who provided them supplies and bases from which to launch raids on the British authorities in Canada.[citation needed]

Burning of Caroline

editOn December 29, 1837, Canadian militia colonel Allan MacNab and Royal Navy captain Andrew Drew led a British force consisting of militiamen and law enforcement officers across the Canada–United States border. The force chased off the crew of Caroline, towed the vessel into the currents of the Niagara River and set her on fire before casting the ship adrift; Caroline proceeded to float over the Niagara Falls and was destroyed. During the confrontation between the British force and the crew, which involved shots being fired, a Black American watchmaker, Amos Durfee, was accidentally killed by an unknown person. As news of the burning spread, a number of American newspapers falsely reported "the death of twenty-two of her crew" when only Durfee was killed. Public opinion in the United States was outraged over the burning, and President Martin Van Buren protested to the government of the United Kingdom over the incident.[citation needed]

British diplomat Henry Stephen Fox summarized the British justification for the incursion in an 1841 letter to John Forsyth:

The steamboat Caroline was a hostile vessel engaged in piratical war against her Majesty's people... it was under such circumstances, which it is to be hoped will never recur, that the vessel was attacked by a party of her Majesty's people, captured and destroyed.[5]

The Attorney General of New York, Willis Hall, responded by stating:

Those of our fellow citizens... single-handed and alone, left our territory and united themselves with a foreign power, have violated no law... they have done no more than has been done again and again by the people of every nation. Your own recollections of history will furnish your minds with hundreds of examples. The Swiss nation have, for hundreds of years, fed all the armies of Europe; and who ever thought of holding them responsible for it? They did no more than Admiral Lord Cochrane did in taking part with South America. They did no more than Lord Byron did, who gave his life to aid the Greeks in breaking the chains of Turkish bondage. They did no more than Lafayette. Gentlemen, I am not deviating from the case further than is necessary to remove the just odium which has been unjustly thrown upon those who joined the insurgents.

Aftermath

editNews of the incident led to a public uproar in the United States, and many people in American towns bordering Canada demanded the U.S. government declare war on Britain. In Canada, the burning was celebrated by the Canadian public and MacNab was knighted for his efforts. Canadian sheriff Alexander McLeod, was arrested in the United States while travelling there in 1840 due to allegations over his role in the death of Durfee. The arrest led to another international incident as the British demanded his release, arguing that McLeod could not be held criminally responsible due to the fact that he was legally carrying out orders of the Crown. McLeod was placed on trial, during which American legal officials unsuccessfully attempted to identify who shot Durfee. McLeod was acquitted of all charges, as witness statements made it clear that he had no involvement in the incident.[6]

In response to the incident, a group of thirteen Americans captured and burned the British merchant steamer Sir Robert Peel while she was in American waters. Van Buren sent General Winfield Scott to prevent further American incursions into Canada.[7][8]

Correspondence between U.S. Secretary of State Daniel Webster and British minister to the United States Lord Ashburton outlined the conditions under which one nation might lawfully violate the territorial sovereignty of another state. The Caroline test (also known as the Caroline doctrine) states that exceptions do exist to territorial inviolability, but "those exceptions should be confined to cases in which the necessity of that self-defense is instant, overwhelming, and leaving no choice of means, and no moment for deliberation".[1][3][9] According to academic Tom Nichols, the Caroline test remains an accepted part of international law today. In 2008, he wrote:

Thus the destruction of an insignificant ship in what one scholar has called a "comic opera affair" in the early 19th century nonetheless led to the establishment of a principle of international law that would govern, at least in theory, the use of force for over 250 years. [sic][10]

See also

edit- Timeline of United States diplomatic history

- Aroostook War, militias mobilized but no battles

- Pig War (1859), US–Britain border dispute in the Pacific Northwest

References

edit- ^ a b Waxman, Matthew C. (August 28, 2018). "The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada". The Lawfare Blog. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- ^ Jennings, R. Y. (1938). "The Caroline and McLeod Cases". American Journal of International Law. 32 (1): 82–99. doi:10.2307/2190632. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2190632.

- ^ a b Moore, John Bassett (1906). A Digest of International Law. Vol. 2. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 25, 409 & 410. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ Greenwood, Christopher (April 2011). "Self-Defence". In Peters, Anne; Wolfrum, Rüdiger (eds.). Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law – via Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Mr Fox to Mr. Forsyth", Hartford Times, January 9, 1841

- ^ Kilbourn, William (June 30, 2008). The Firebrand: William Lyon Mackenzie and the Rebellion in Upper Canada. Toronto: Dundurn. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-77070-324-7.

- ^ Fuller, L. N. (1923). "Chapter 7: British Steamer is Burned by Patriots". Northern New York In The Patriot War.

- ^ McLaughlin, Shaun J. (February 13, 2012). "Searching for a Pirate's Lost Lair". Thousand Islands Magazine.

- ^ Wood, Michael (May 17, 2018). "Chapter 2: The Caroline Incident—1837". The Use of Force in International Law: A Case-Based Approach. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198784357.

- ^ Nichols, Thomas (2008). The Coming Age of Preventive War. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8122-4066-5

Further reading

edit- Craig Forcese; Destroying the Caroline The Frontier Raid That Reshaped the Right to War, Irwin Law Inc., 2018; ISBN 1552214788

Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2507

- Matthew C. Waxman, The Caroline Affair in the Evolving International Law of Self-Defense, Columbia Public Law Research Paper No. 14-600 (2018). PDF available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu

- Howard Jones; To the Webster-Ashburton Treaty: A Study in Anglo-American Relations, 1783-1843 University of North Carolina Press, 1977

- Kenneth R. Stevens; Border Diplomacy- The Caroline and McLeod Affairs in Anglo-American-Canadian Relations, 1837-1842 University of Alabama Press, 1989; ISBN 0-8173-0434-7

- Wiltse, Charles M. "Daniel Webster and the British Experience." Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society Vol. 85. (1973) pp 55-87 online.

External links

edit- Media related to Caroline Affair at Wikimedia Commons

- The Avalon Project at Yale Law School: The Webster-Ashburton Treaty and The Caroline Case

- Contemporary newspaper accounts of the Caroline Affair