46°07′41″N 91°41′14″E / 46.128186°N 91.687306°E

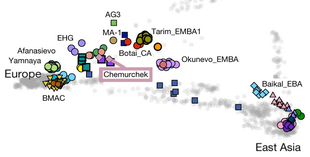

Chemurchek culture and contemporary cultures and polities circa 2000 BCE.[1][2][3][4] Chemurchek statues have also been found on the northern slopes of the eastern Tian Shan.[5] | |

| Geographical range | South Siberia |

|---|---|

| Dates | 2750-1900 BCE.[7] |

| Preceded by | Afanasievo culture |

| Followed by | Munkhkhairkhan culture Sagsai culture Deer stones culture Subeshi culture |

The Chemurchek culture (Ch:切木尔切克, Qièmùěrqièkè; Ru: Чемурчекская культура), also called Khemtseg, Hemtseg, Qiemu’erqieke, Shamirshak (2750-1900 BCE), is a Bronze Age archaeological culture of western Mongolia and the borders of neighbouring countries, such as the Dzungarian Basin of Xinjiang and eastern Kazakhstan.[7] It immediately follows the Afanasievo culture, and is contemporary with the early Tarim Mummies to the south and the Okunev culture to the north.[9] The Chemurchek burials are characterized by large rectangular stone fences, built around collective tombs. The mortuary position of the deceased (supine position with flexed legs) is similar to that of the Afanasievo culture, but the Chemurchek culture is considered as distinct. The name "Chemurchek culture" is derived from the Chemurchek cemetery[10] in Altay City of Chinese Xinjiang.[11] Chemurchek sites have been identified from western Mongolia to areas as far west as the Ili valley (Bortala Mongol Autonomous Prefecture).[12]

Characteristics

editAnthropomorphic standing stones were erected next to the tombs, on their eastern side.[7][14] Their faces are flattened with a straight nose and globular eyes. They appear to be naked as pectoral muscles seem to be depicted.[15] They far predate and are very different from Turkic balbal statues found in the same general area but dated to the 7th-10th centuries CE.[16] They are highly similar to Western European anthropomorphic stelae, suggesting the transfer of cultural characteristics through migration.[17] A more developed tradition of anthropomorphic stelae existed in the contemporary Okunev culture to the north, in the Minusinsk basin (c. 2550/2500 – c. 1900/1700 BCE).[18]

In the tombs, artifacts have been recovered, such as stone bowls, bone tools, ceramics (grey wares with sophisticated patterns of incised decoration), or metal jewelry.[7] Bronze artifacts too are available.[19] Bronze tools include knives, awls, spearheads and arrowheads. Bronze was cast in open or composite stone molds, and seems to have been a focus of economic production.[12]

Dental analysis has shown that the Chemurchek culture consumed ruminant dairy products.[7]

The people of the Chemurchek culture were apparently descendants of Afanasievo populations intermixed with local populations.[1] Their genetic profile shows a contribution of about 50% from the Afanasievans, combined with about 30% of Ancient North Eurasian (an ancient Siberian substrate represented by the Tarim mummies of sample Tarim_EMBA1), and small proportions of Ancient Northeast Asian (Baikal_EBA) and BMAC (Geoksyur_EN).[13]

In the Altai Mountains and to the southeast, Afanasievans seem to have coexisted with the early period of the Chemurchek culture for some time, as some of their burials are contemporary and some of the artifacts of the burials coincide.[20] The Chemurchek culture had various characteristics of West European origin.[21]

Another Chemurcheck burial site was discovered in Yagshiin khuduu in Bulgan soum, Khovd aimag, which contained "the oldest kurgan stelae" discovered so far in Mongolia, dated to c. 2500-2000 BCE.[22]

European connections

editArchaeologist Alexey Kovalev has remarked on the similarities between the material and tomb cultures of the Chemurcheks and those of Southern France, leading him to suggest a migratory origin for the Chemurchek culture from Western Europe and more specifically southern France.[24]

The Chemurchek statues have a lot in common with southern France statues of the late 4th millennium such as "La Dame de Saint-Sernin" or the "Statue-menhir de Maison-Aube".[25] Kovalev further suggests that the Chemurchek culture may be associated with Proto-Tokharians, who must have migrated to the east around this period, and whose Western Indo-European language is closest to proto-Germanic and proto-Italian, corresponding to the broad geographical area encompassing southern France. The language of the Chemurchek/Proto-Tocharians may have originated from the same general location in Western Europe, as did their burial and statuary styles.[26][17] According to Alexey Kovalev:

Taken together, the architecture of burial constructions, the tradition of collective burials in crypts, the form and ornamentation of vessels, the style of stone statues, the paintings on walls of burialchambers, the slate plaques and images of importantdeities reveal a strong analogy with materials of the Middle-Final Neolithic period of Western Europe. The complex of specific attributes that appeared in Dzhungaria from c. 2700-2600 BCE is very close to those found at Final Neolithic sites in southern France, the Jura Mountains, and western Switzerland c. 3200-2600 BCE. The transfer of such a complex set of cultural traditions such a great distance seems impossible without the migration of ancient people.

— Alexey Kovalev, The Chemurchek (Qie'muerqieke) cultural phenomenon [30]

In particular, regarding the architecture of the tombs: "the unique architectural technique of constructing perimeter embankments lined with stone facades was used before the appearance of the Chemurchek monuments only during the construction of megalithic tombs of France and the British Isles".[31] Three main types of Chemurchek tombs are recorded: the Alkabek, Bulgan and Kermuqi types.[32]

Gallery

edit-

Chemurchek funerary and ritual structures

-

Chemurchek barrow with statue-menhir (Yagshiin khodoo 3), "Bulgan type" mound.[33]

-

Chemurchek burials, carbon dates

-

Funerary statue from Chemurchek cemetery (Burial mound M2). Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region Museum.[34][35]

-

Chemurchek sanctuary Hulagash (Bayan-Ulgii aimag, Mongolia) Burial, circa 2500 BCE

-

Chemurchek sanctuary Hulagash (Bayan-Ulgii aimag, Mongolia) Burial, forensic reconstruction of the skull, circa 2500 BCE

-

Hypothesized horse transport technology in use during the Chemurchek culture period.[36]

-

Stone pot with two mouths, 4200-3900 BCE, Chemurcheck cemetery, Altay City.

-

Stone ware, Yagshiin khuduu in Bulgan soum, Khovd aimag. National Museum of Mongolia

-

Bronze earring, Yagshiin khuduu in Bulgan soum, Khovd aimag. National Museum of Mongolia

-

Stone fence and burial of Khemtseg culture, Avyn Khukh Uul, Bulgan, Khovd, Mongolia

-

Stone fence and burial of Khemtseg culture, Avyn Khukh Uul, Bulgan, Khovd, Mongolia

-

Chronological table of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Mongolia.[37]

References

edit- ^ a b Zhang et al. 2021.

- ^ Kovalev 2022, p. 769, Fig.1.

- ^ Bobrov, Vladimir (January 2021). "Shigir idol: Origin of monumental sculpture and ideas about the ways of preservation of the representational tradition". Quaternary International. 573: Fig. 1. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.08.041.

- ^ Chen, Kwang-tzuu; Hiebert, Fredrik T. (June 1995). "The Late Prehistory of Xinjiang in Relation to Its Neighbors". Journal of World Prehistory. 9 (2): 271.

While this culture is known primarily from the excavations at Ke'ermuqi, many such burials are known in the Altai foothills, for example, in the counties of Habahe, Jimunai, and Bu'erqin (IAX, 1981a) and new excavations have been initiated in this region. The distribution of Ke'ermuqi type burials indicates that they are widespread along the foothills of the Zhunge'er Basin but are not found across the Tianshan Mountains. In western Zhunge'er, Ke'ermuqi type tombs have been identified at the site of A'erkate in the Yili Valley (Li Yuchun, 1962) and at the sites of Adongquelu and Aershate near Wenquan (Li, 1988). The Ke'ermuqi culture extended to the southern parts of the Zhunge'er Basin with burials found near Ulumuqi (Wang Mingzhe, 1984; IAX, 1985b, pi. 148) and near Mulei (Huang and Dai, 1986). Also, a Ke'ermuqi-style gray incised round-bottomed jar was found at Kan'erzi, in Qitai County (CCQ, 1982), in the region of the Yanbulake] eastern Xinjiang oasis cultures.

- ^ Kovalev 2022, p. 771.

- ^ a b Kovalev 2012, p. 124, statue 55.

- ^ a b c d e Jeong et al. 2020.

- ^ Zhang, Fan; Ning, Chao; Scott, Ashley (November 2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 256–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..256Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8580821. PMID 34707286.

- ^ Gantulga, Jamiyan-Ombo (21 November 2020). "Ties between steppe and peninsula: Comparative perspective of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Мongolia and Кorea". Proceedings of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences: 65–88. doi:10.5564/pmas.v60i4.1507. ISSN 2312-2994.

- ^ 47°46′50″N 87°51′36″E / 47.780636°N 87.860069°E

- ^ Museum notice

- ^ a b Chen, Kwang-tzuu; Hiebert, Fredrik T. (June 1995). "The Late Prehistory of Xinjiang in Relation to Its Neighbors". Journal of World Prehistory. 9 (2): 271.

Bronze artifacts are relatively few in comparison with the Siberian materials and consist mainly of tools such as knives, awls, spearheads, and arrowheads. However, stone molds for bronze casting suggest an economic focus on metal production, unexpected on the basis of the tomb inventory. These include composite molds for spades and an open mold for knives and awls (IAX, 1981a). The artifact assemblage from Ke'ermuqi burials is also distinguished from the highland assemblages by its emphasis on stone objects: jars, bowls, cups with single handles (including one cow-headed handle), mortars and pestles, stone lamps, and arrowheads.

- ^ a b Zhang, Fan (November 2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 256–261. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8580821.

- ^ Bemmann, J.; Brosseder, U. (2017). A LONG STANDING TRADITION – STELAE IN THE STEPPES WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE SLAB GRAVE CULTURE. ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY OF CENTRAL ASIA Materials of the II International conference (Ulan-Ude, 4–6th December, 2017). Ulan-Ude The Buryat Scientific Center SB RA 2017. p. 20. ISBN 978-5-7925-0494-3.

- ^ Kovalev 2011, p. 15 "The specific features of the Chemurchek statues are the following; the flattened face is marked by protruding contour and a straight relief nose is usually connected with it. The eyes are marked by protruding circles or disks. A girdle or necklace sometimes consisting of several rows is modeled on the neck. Judging from indicated pectoral muscles, the figured are portrayed in the nude."

- ^ Kovalev 2011.

- ^ a b Kovalev 2022.

- ^ Bemmann, J.; Brosseder, U. (2017). A LONG STANDING TRADITION – STELAE IN THE STEPPES WITH A SPECIAL FOCUS ON THE SLAB GRAVE CULTURE. ACTUAL PROBLEMS OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGY OF CENTRAL ASIA Materials of the II International conference (Ulan-Ude, 4–6th December, 2017). Ulan-Ude The Buryat Scientific Center SB RA 2017. p. 20. ISBN 978-5-7925-0494-3.

The use of stelae in the Minusinsk Basin is similar to that in Mongolia. Starting with the Early Bronze Age, stelae were erected during the Okunevo culture (c. 2550/2500-1900/1700 BCE)

- ^ Betts, Jia & Abuduresule 2019.

- ^ Kovalev, A. A., and Erdenebaatar, D. (2009). Discovery of new cultures of the Bronze Age in Mongolia according to the data obtained by the international Central Asian archaeological expedition. In Bemmann, J., Parzinger, H., Pohl, E., and Tseveendorzh, D. (eds.), Current Archaeological Research in Mongolia, Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn, p.158: "Two 14C-dates that have come from the charcoal found in the earliest (ritual) pit of Chemurchek barrow No. 2 appeared to be in the same period as the four radiocarbon dates from the charcoal in the fi lling of the burial pit of barrow No. 1 that belongs to the Afanasievo culture. It may indicate that during the earliest period of existence of the Chemurchek culture, its population in the Altai region maybe coexisted with population of the Afanasievo culture. A pillar, erected at the eastern side of an Afanasievo culture barrow (Fig. 1.1), as well as the finding of a bone arrowhead (Fig. 1.4), which is similar to arrowheads from Kulala Ula 1 and Kara Tumsik barrows (Fig. 2.10,12), also confirm this proposition."

- ^ Kovalev, A.A.; Solodovnikov, K.N.; Munkhbayar, Ch.; Erdene, M.; Nechvaloda, A.I.; Zubova, A.V. (2 March 2020). "Paleoanthropological study of a skull from a burial at the Chemurchek sanctuary Hulagash (Bayan-Ulgii aimag, Mongolia)". Vestnik Arheologii, Antropologii I Etnografii. 1 (48): 78–95. doi:10.20874/2071-0437-2020-48-1-8. S2CID 213820119.

the so-called Chemurchek cultural phenomenon — a set of characteristics of West European origin, which appeared there no later than 2700–2600 BC

- ^ "Collection of the National Museum of Mongolia: The Oldest Kurgan Stelae discovered in Mongolia". MONTSAME News Agency.

- ^ 46°05′36″N 91°26′41″E / 46.09333°N 91.4447°E

- ^ Kovalev 2011, pp. 9–10 "Where are all the specific features of Chemurchek mounds represented as a whole complex? It emerges that this situation is found in western and southern France. Besides the analogies in the construction of burial mounds, we find here analogies in the form and ornamentation of vessels, and in the decoration of stone sculptures. All the analogies from Western Europe date from the period preceding the appearance of Chemurchek monuments in the Altai. Nothing like those shapes of burial construction and pottery has been ever found among the monuments of the 3rd millennium BCE on the territory between France and Altai. This is why we suppose that some part of the population of south-western Europe migrated to the Altai at the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE."

- ^ Kovalev 2011, p. Fig 31-10 p.17: "In this paper we attempt to present elements of Chemurchek sulture which have no other analogies except in the Neolithic of France (...) Evidently, the fact that all these elements of culture had been transferred over 6,500 kilometers to the Mongolian Altai can only be explained by migration"

- ^ Kovalev 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Kovalev 2012, p. 116, statue 54.

- ^ 46°07′18″N 91°34′18″E / 46.1218°N 91.5718°E

- ^ "Collection of the National Museum of Mongolia: The Oldest Kurgan Stelae discovered in Mongolia". MONTSAME News Agency.

- ^ Kovalev 2022, p. 789.

- ^ Kovalev 2012, p. 127.

- ^ File

- ^ Kovalev 2012, p. 116-117, statue 54.

- ^ 47°49′39″N 87°51′35″E / 47.8274°N 87.8598°E

- ^ Kovalev 2012, p. 22, statue 7.

- ^ Taylor, William Timothy Treal (22 January 2020). "Early Pastoral Economies and Herding Transitions in Eastern Eurasia". Scientific Reports. 10: Figure 8, a). doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57735-y. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ Gantulga, Jamiyan-Ombo (21 November 2020). "Ties between steppe and peninsula: Comparative perspective of the Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Мongolia and Кorea". Proceedings of the Mongolian Academy of Sciences: 65–88. doi:10.5564/pmas.v60i4.1507. ISSN 2312-2994.

Sources

edit- Betts, A.; Jia, P.; Abuduresule, I. (1 March 2019). "A new hypothesis for early Bronze Age cultural diversity in Xinjiang, China". Archaeological Research in Asia. 17: 204–213. doi:10.1016/j.ara.2018.04.001. ISSN 2352-2267.

- Jeong, Choongwon; Wang, Ke; Wilkin, Shevan; Taylor, William Timothy Treal; Miller, Bryan K.; Bemmann, Jan H.; Stahl, Raphaela; Chiovelli, Chelsea; Knolle, Florian; Ulziibayar, Sodnom; Khatanbaatar, Dorjpurev; Erdenebaatar, Diimaajav; Erdenebat, Ulambayar; Ochir, Ayudai; Ankhsanaa, Ganbold; Vanchigdash, Chuluunkhuu; Ochir, Battuga; Munkhbayar, Chuluunbat; Tumen, Dashzeveg; Kovalev, Alexey; Kradin, Nikolay; Bazarov, Bilikto A.; Miyagashev, Denis A.; Konovalov, Prokopiy B.; Zhambaltarova, Elena; Miller, Alicia Ventresca; Haak, Wolfgang; Schiffels, Stephan; Krause, Johannes; Boivin, Nicole; Erdene, Myagmar; Hendy, Jessica; Warinner, Christina (12 November 2020). "A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia's Eastern Steppe". Cell. 183 (4): 890–904. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 7664836. PMID 33157037. S2CID 214725595.

- Kovalev, Alexey (2011). "The Great Migration of the Chemurchek People from France to the Altai in the Early 3rd Millenium BCE". International Journal of Eurasian Studies. 1: 1–58.

- Kovalev, Alexey (2012). Ancient statue-menhirs in Chemurchek and surrounding territories 2012 (Древнейшие статуи Чемурчека и окружающих территорий 2012) (Naučn. izd ed.). Sankt-Peterburg: LDPrint. ISBN 978-5-905585-03-6.

- Kovalev, Alexey (2022). "Megalithic traditions in the Early Bronze Age of the Mongolian Altai: the Chemurchek (Qie'muerqieke) cultural phenomenon". Megaliths of the World Vol. 2. Oxford Archaeopress.

- Zhang, Fan; Ning, Chao; Scott, Ashley; Fu, Qiaomei; Bjørn, Rasmus; Li, Wenying; Wei, Dong; Wang, Wenjun; Fan, Linyuan; Abuduresule, Idilisi; Hu, Xingjun; Ruan, Qiurong; Niyazi, Alipujiang; Dong, Guanghui; Cao, Peng; Liu, Feng; Dai, Qingyan; Feng, Xiaotian; Yang, Ruowei; Tang, Zihua; Ma, Pengcheng; Li, Chunxiang; Gao, Shizhu; Xu, Yang; Wu, Sihao; Wen, Shaoqing; Zhu, Hong; Zhou, Hui; Robbeets, Martine; Kumar, Vikas; Krause, Johannes; Warinner, Christina; Jeong, Choongwon; Cui, Yinqiu (November 2021). "The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies". Nature. 599 (7884): 256–261. Bibcode:2021Natur.599..256Z. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 8580821. PMID 34707286. S2CID 240072904.