Coffinite is a uranium-bearing silicate mineral with formula: U(SiO4)1−x(OH)4x.

| Coffinite | |

|---|---|

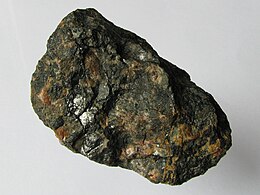

Pitchblende and coffinite in a sample from a Czech mine | |

| General | |

| Category | Nesosilicate |

| Formula (repeating unit) | U(SiO4)1−x(OH)4x |

| IMA symbol | Cof[1] |

| Strunz classification | 9.AD.30 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Crystal class | Ditetragonal dipyramidal (4/mmm) H-M symbol: (4/m 2/m 2/m) |

| Space group | I41/amd |

| Unit cell | a = 6.97 Å, c = 6.25 Å; Z = 4 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black (from organic inclusions; pale to dark brown in thin section |

| Crystal habit | Rarely as crystals, commonly as colloform to botryoidal incrustations, fibrous, pulverulent masses |

| Fracture | Irregular to subconchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle to friable |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5–6 |

| Luster | Dull to adamantine |

| Streak | Grayish black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque, transparent on thin edges |

| Specific gravity | 5.1 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+/−) |

| Refractive index | nα = 1.730–1.750 nβ = 1.730–1.750 |

| Birefringence | δ = 1.730 |

| Pleochroism | Moderate; pale yellow-brown parallel to and medium brown perpendicular to long axis |

| Alters to | Metamict |

| Other characteristics | |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] |

It occurs as black incrustations, dark to pale-brown in thin section. It has a grayish-black streak. It has a brittle to conchoidal fracture. The hardness of coffinite is between 5 and 6.

It was first described in 1954 for an occurrence at the La Sal No. 2 Mine, Beaver Mesa, Mesa County, Colorado, US,[5] and named for American geologist Reuben Clare Coffin (1886–1972).[3] It has widespread global occurrence in Colorado Plateau-type uranium ore deposits of uranium and vanadium. It replaces organic matter in sandstone and in hydrothermal vein type deposits.[3] It occurs in association with uraninite, thorite, pyrite, marcasite, roscoelite, clay minerals and amorphous organic matter.[3]

Composition

editCoffinite's chemical formula is U(SiO4)1−x(OH)4x.[6][15] X-ray powder patterns from samples of coffinite allowed geologists to classify it as a new mineral in 1955.[6] A comparison to the x-ray powder pattern of zircon (ZrSiO4) and thorite (ThSiO4) was the basis for this classification.[7] Preliminary chemical analysis indicated that the uranous silicate exhibited hydroxyl substitution.[7] The results of Sherwood's preliminary chemical analysis were based on samples from three locations. Hydroxyl bonds and silicon-oxygen bonds also proved to exist after infrared absorption spectral analyses were performed.[8] The hydroxyl substitution occurs as (OH)44− for (SiO4)4−.[8] The hydroxyl constituent in coffinite later proved to be nonessential in the formation of a stable synthetic mineral.[9] Recent electron microprobe analysis of the submicroscopic crystals uncovered an abundance of calcium, yttrium, phosphorus, and minimal lead substitutions along with traces of other rare earth elements.[9]

Crystal structure

editCoffinite is isostructural with the orthosilicates zircon (ZrSiO4) and thorite (ThSiO4).[16] Stieff et al. analyzed coffinite using the x-ray powder diffraction technique and determined that it has a tetragonal structure.[8] Occurring naturally with U4+ cations, the UO8 triangular dodecahedra coordinate with edge-sharing, alternating SiO4 tetrahedra in chains along the c-axis.[12] The central uranium site of coffinite is surrounded by eight SiO4 tetrahedra. The lattice dimensions of naturally-occurring and synthetic coffinite are similar, with a naturally-occurring sample from Arrowhead Mine, Mesa County, Colorado having a=6.93kx, c=6.30kx, and a sample synthesized by Hoekstra and Fuchs having a=6.977kx and c=6.307kx.[15][13]

Physical properties

editInitial examination of coffinite by Stieff et al. described the mineral as black in color with an adamantine luster, indistinguishable from uraninite (UO2).[8] Additionally, the discoverers reported that although no cleavage is seen in coffinite, it does exhibit subconchoidal fracturing and is very fine grained. Initial samples showed a brittle texture and a hardness between 5 and 6, with a specific gravity of 5.1.[8] Later samples from Woodrow Mine in New Mexico collected by Moench showed fibrous internal structure and exceptional crystallization.[10] A polished thin section of coffinite has a brown color and shows anisotropic transmission of light.[10] Optical analysis yielded a refractive index of about 1.74.[10]

Geological occurrence

editCoffinite was first discovered in sedimentary uranium deposits in the Colorado Plateau region,[11] but has also been discovered in sedimentary uranium deposits and hydrothermal veins in many other locations.[9] Samples of coffinite from the Colorado Plateau were found with black fine-grained low-valence vanadium minerals, uraninite and finely dispersed black organic material.[15][8] Other materials associated with later finds from the same region were clay and quartz.[11] In vein deposits of the Copper King Mine in Colorado, coffinite was also found to occur with uraninite and pitchblende.[8] Coffinite is metastable[14] compared to uraninite and quartz, thus formation of coffinite requires a uranium source in reducing conditions, as evidenced by the associated presence of low-valence vanadium minerals.[8] Silica-rich solution provides such a reducing condition in cases where coffinite results as an alteration product of uraninite.[12] Hansley and Fitzpatrick also noted that the brownish color of their coffinite samples was caused by organic material, leading them to conclude that coffinite can also form in low temperature conditions if organic carbon is present.[9] This finding is consistent with the coffinite samples of the Colorado Plateau, which included fossilized wood.[11] In China, coffinite can be found in granite in addition to sandstone.[11] Hansley and Fitzpatrick concluded that coarse-grained coffinite most likely forms in high temperature environments.[9] Coffinite and uraninite precipitate inside brecciated and fractured regions of altered granite at pressures between 500 and 800 bars and temperatures at 126 to 178 °C.[11]

Special characteristics

editA large percentage of the Earth's uranium supply is contained in coffinite deposits,[17] which is significant because of uranium's use in nuclear energy. Sedimentary deposits contain the most radioactive samples,[8] as evidenced by the intensely radioactive coffinite found in the Colorado Plateau.[6] Researchers at Harvard University, the United States Geological Survey (USGS), and several other institutions attempted unsuccessfully to synthesize coffinite in the mid-1950s after its initial discovery.[6] In 1956, Hoekstra and Fuchs managed to create stable samples of synthetic coffinite. All of this research was conducted for the United States Atomic Energy Commission.[13]

References

edit- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ a b c d Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (2005). "Coffinite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineral Data Publishing. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Webmineral data

- ^ a b Coffinite, Mindat.org

- ^ a b c d e Stieff, L.R.; Stern, T.W; Sherwood, A.M. (1955). "Preliminary Description of Coffinite – A New Uranium Mineral". Science. 121 (3147): 608–609. Bibcode:1955Sci...121..608S. doi:10.1126/science.121.3147.608-a. hdl:2027/mdp.39015095016906.

- ^ a b c Fuchs, L.H.; Gebert, E. (1958). "X-Ray Studies of Synthetic Coffinite, Thorite and Uranothorites". American Mineralogist. 43: 243–248.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Stieff, L.R.; Stern, T.W; Sherwood, A.M. (1956). "Coffinite, a Uranous Silicate with Hydroxyl Substitution – A New Mineral". American Mineralogist. 41: 675–688.

- ^ a b c d e f Hansley, P.L.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. (1989). "Compositional and Crystallographic Data on REE-Bearing Coffinite from the Grants Uranium Region, Northwestern New-Mexico". American Mineralogist. 74: 263–270.

- ^ a b c d Moench, R.H. (1962). "Properties and Paragenesis af Coffinite from Woodrow Mine, New Mexico". American Mineralogist. 47: 26–33.

- ^ a b c d e f Min, M.Z.; Fang, C.Q.; Fayek, M. (2005). "Petrography and Genetic History of Coffinite and Uraninite from the Liueryiqi Granite-Hosted Uranium Deposit, SE China". Ore Geology Reviews. 26 (3–4): 187–197. doi:10.1016/j.oregeorev.2004.10.006.

- ^ a b c Zhang, F. X.; Pointeau, V.; Shuller, L. C.; et al. (2009). "Response of Synthetic Coffinite to Energetic Ion Beam Irradiation". American Mineralogist. 94: 916–920. doi:10.2138/am.2009.3111. S2CID 73581946.

- ^ a b c Hoekstra, H.R.; Fuchs, L.H. (1956). "Synthesis of Coffinite-USiO4". Science. 123 (3186): 105. Bibcode:1956Sci...123..105H. doi:10.1126/science.123.3186.105.

- ^ a b Guo X.; Szenknect S.; Mesbah A.; Labs S.; Clavier N.; Poinssot C.; Ushakov S.V.; Curtius H.; Bosbach D.; Rodney R.C.; Burns P.; Navrotsky A. (2015). "Thermodynamics of Formation of Coffinite, USiO4". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112 (21): 6551–6555. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.6551G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1507441112. PMC 4450415. PMID 25964321.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Robert A.; Montenari, Michael (2019). "Computer modeling of Zircon (ZrSiO4)—Coffinite (USiO4) solid solutions and lead incorporation: Geological implications". Stratigraphy & Timescales. 4: 217–227. doi:10.1016/bs.sats.2019.08.005. ISBN 9780128175521. S2CID 210256739 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Pointeau, V.; et al. (2009). "Synthesis and Characterization of Coffinite". Journal of Nuclear Materials. 393 (3): 449–458. Bibcode:2009JNuM..393..449P. doi:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2009.06.030.

- ^ Deditius, Arthur P., Utsunomiya, Satoshi, Ewing, Rodney C. (2008) The Chemical Stability of Coffinite, USiO4 Center Dot NH(2)O; 0 < N < 2, Associated With Organic Matter: A Case Study from Grants Uranium Region, New Mexico, USA. Chemical Geology, 251, 33-49.