Danilo Dolci (28 June 1924 – 30 December 1997) was an Italian social activist, sociologist, popular educator and poet. He is best known for his opposition to poverty, social exclusion and the Mafia in Sicily, and is considered to be one of the protagonists of the non-violence movement in Italy. He became known as the "Gandhi of Sicily".[1]

Danilo Dolci | |

|---|---|

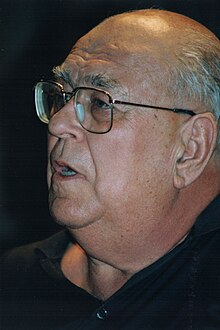

Danilo Dolci in 1992 | |

| Born | 28 June 1924 |

| Died | 30 December 1997 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | "Gandhi of Sicily" |

| Occupation(s) | Social activist, sociologist, popular educator and poet |

| Known for | Prominent antimafia activist and protagonist of the non-violence movement in Italy |

In the 1950s and 1960s, Dolci published a series of books (notably, in their English translations, To Feed the Hungry, 1955, and Waste, 1960) that stunned the outside world with their emotional force and the detail with which he depicted the desperate conditions of the Sicilian countryside and the power of the Mafia. Dolci became a kind of cult hero in the United States and Northern Europe; he was idolised, in particular by idealistic youngsters, and support committees were formed to raise funds for his projects.[2]

In 1958 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize, despite being an explicit non-communist.[1] He was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which in 1947 received the Nobel Peace Prize along with the British Friends Service Council, now called Quaker Peace and Social Witness, on behalf of all Quakers worldwide.[3] Among those who publicly voiced support for his efforts were Carlo Levi, Erich Fromm, Bertrand Russell, Jean Piaget, Aldous Huxley, Jean-Paul Sartre and Ernst Bloch. In Sicily, Leonardo Sciascia advocated many of his ideas. In the United States his proto-Christian idealism was absurdly confused with communism. He was also a recipient of the 1989 Jamnalal Bajaj International Award of the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation of India.[4]

Salvatore Farina, who met him personally, described Dolci «an exemplary human being who exuded charisma from every pore».[5]

Early years

editDanilo Dolci was born in the Karstic town of Sežana (now in Slovenia), at the time part of the Italian border region known as Julian March. His father was an agnostic Sicilian railway official, while his mother, Meli Kokelj, was a deeply Catholic local Slovene woman. The young Danilo grew up in Mussolini's fascist state. As a teenager Dolci saw Italy enter into World War II. He worried his family by tearing down any Fascist war posters he came across.[6]

"I had never heard the phrase 'conscientious objector'", Dolci later said, "and I had no idea there were such persons in the world, but I felt strongly that it was wrong to kill people and I was determined never to do so."[7] He tried to escape from the authorities who suspected him of tearing down the posters, but he was caught while trying to reach Rome and ended up in jail for a short time. He refused to enlist in the army of the Republic of Salò, Mussolini's puppet state after the Allied invasion in 1943.[6]

Dolci was inspired by the work of the Catholic priest Don Zeno Saltini who had opened an orphanage for 3,000 abandoned children after World War II. It was housed in a former concentration camp at Fossoli near Modena in Emilia Romagna, and was called Nomadelfia: a place where fraternity is law. In 1950 Dolci quit his very promising architecture and engineering studies in Switzerland at the age of twenty-five, gave up his middle class standard of living and went to work with the poor and unfortunate. Dolci set up a similar commune called Ceffarello.[2][6]

Don Zeno was being harassed by officials who felt he was a communist, and even the Vatican turned against Don Zeno, calling him the "mad priest". The authorities decided to put the orphans into asylums and close down both Nomadelphia and Ceffarello. Dolci had to sit by and watch as government forces took off with many of the commune's children, and had to gather up all his energy in the building of a new Nomadelphia. By 1952, he was ready to move on and work elsewhere.[6]

In Sicily

editIn 1952 Dolci decided to head for "the poorest place I had ever known" — the squalid fishing village of Trappeto in western Sicily about 30 km west of Palermo. During a previous visit to Sicily's Greek archaeological sites he had become acutely aware of the squalid rural poverty. Towns without electricity, running water or sewers, peopled by impoverished citizens barely surviving on the edge of starvation, largely illiterate and unemployed, suspicious of the state and ignored by their Church.[2][6]

"Coming from the North, I knew I was totally ignorant", Dolci wrote later. "Looking all around me, I saw no streets, just mud and dust ... I started working with masons and peasants, who kindly, gently, taught me their trades. That way my spectacles were no longer a barrier. Every day, all day, as the handle of hoe or shovel burned the blisters deeper, I learned more than any book could teach me about this people's struggle to exist".[6]

In Trappeto Dolci started an orphanage, helped by Vincenzina Mangano, the widow of a fisherman and trade unionist whom he rescued from penury and whose five children he adopted as his own. Later, he moved uphill to nearby Partinico, where he tried to organise landless peasants into co-operatives. Dolci started using hunger strikes, sit-down protests and non-violent demonstrations as methods to force the regional and national government to make improvements in the poverty stricken areas of the island. Eventually, he became known as the "Gandhi of Sicily", as a French journalist had dubbed him.[1][8]

Peaceful protest

editThroughout his career in Sicily, Dolci used methods of peaceful protest, with one of his most famous hunger strikes occurring in November 1955, when he fasted for a week in Partinico to draw attention to the misery and violence in the area and to promote the building of a dam over the Iato River, which roared down in the winter rains and dried up in the nine arid months, that could provide irrigation for the entire valley.[9]

One technique that he innovated was the "strike in reverse" (working without pay), which initiated unauthorized public works projects for the poor. This earned him his first notoriety in 1956, when he gathered some 150 unemployed men to mend a public road.[10][11] The police called it obstruction; his helpers walked away; he lay down on the road and was arrested. Skilfully, he drummed up publicity. Famous lawyers such as Piero Calamandrei offered to defend him for free.[12] Famous writers, such as Ignazio Silone, Alberto Moravia, Carlo Levi, among others, protested. The Palermo court acquitted Dolci and his two dozen co-defendants of resisting and insulting the police, but sentenced them to 50 days' imprisonment (time they had already served) and a 20,000 lire (US$32) fine for "having invaded ground that belonged to the government."[13][14] On his release he resumed the campaign for the dam on the Iato river and work would eventually start in February 1963.[15]

Subsequently, he started a campaign for a dam in the Belice river, to avoid the valley from becoming a wasteland and providing jobs to stop the emigration of workers.[15] Dolci proclaimed a week of mourning and with 30 associates conducted a hunger strike in the town square of Roccamena in March 1965. He then led a delegation from mayors of 19 towns in the valley to Rome to plead for the dam, parading to Parliament carrying banners protesting that "the Belice valley is dying".[16] In January 1968, the area was hit by an earthquake which destroyed much of the Belice valley. Dolci actively assisted victims and months after the disaster he announced demonstrations and hunger strikes to demand immediate help for homeless families living in tents.[17] Funds for relief and reconstruction were siphoned off by greedy administrators, and "Belice" has since become an Italian by-word for political corruption.[18]

Antimafia

editDolci became aware of the stranglehold of the Mafia upon the poor in Sicily. He did not attack the Mafia at first but he did come up against them at once challenging their monopoly of water supply with the project of the Iato River dam.[9] Initially, his actions resulted in threats by the Mafia and disapproval of the authorities; later he became too well known in Italy and abroad to be dealt with without too much adverse publicity.[19]

He began his crusade against the Mafia by claiming that government officials were receiving help in their elections from Cosa Nostra. Rather than making his accusations only in Sicily, he traveled to Rome to participate before the Antimafia Commission, which was established in 1963, to ensure that his worries about the Mafia in Sicily were heard. His willingness to stand up to the Mafia in his quest to improve the living conditions of Sicilians helped him to gain the confidence of the locals.[6]

Throughout 1963 and 1964, Dolci and his assistant Franco Alasia had been gathering evidence on the links between the Mafia and politicians for the commission. At a press conference in September 1965, they presented dozen of testimonies of people who had supposedly seen Bernardo Mattarella (father of the current President of Italy, Sergio Mattarella) and Calogero Volpe meeting with leading mafiosi. Mattarella and Volpe sued Dolci and Alasia for libel.[20][21]

Tried for libel

editIn the ensuing two-year trial, dozens of witnesses were heard and many documents were considered. When the Court refused to allow new evidence from witnesses, Dolci and Alasia decided that the trial was a travesty. They announced that under these circumstances they would no longer attempt to defend themselves.[22] The remainder of the trial, therefore, took place with Dolci and Alasia absent from the courtroom. Dolci responded by broadcasting his opinions over a private radio station, which was promptly closed.[20][23]

On June 21, 1967, the Court of Rome determined that Mattarella had offered reliable evidence of his opposition to the Mafia in the entire course of his political career. The statements collected by the defendants – Dolci and his assistant Alasia – were considered nothing more than "deplorable gossip, malicious rumour or even simple lies." The Court was of the opinion that Mattarella "never had relations with the Mafia environment."[24][25] The results of the investigation were published in 1966 in the book Chi gioca solo (The Man Who Plays Alone).

Dolci made an application for an amnesty, but was sentenced to two years imprisonment for libel along with heavy fines. Alasia received a sentence of one and a half year. They never served the verdict, because of a pardon. It would have been too scandalous to send Dolci to prison and the sentence was cancelled. Mattarella had won the trial but lost a cabinet post in the new government of Aldo Moro. In appeal the sentences were confirmed in 1973. "To each his own responsibility before today's public opinion and tomorrow's history", Dolci commented on the sentence.[26]

Popular educator

editIn the vein of Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., Dolci believed that conflicts in society were inevitable, but that any attempt to resolve conflicts by violence or other coercive means would eventually backfire. In the short run violent solutions might offer an advantage; in the long run, however, all positions depending on such dominative means would collapse in renewed violence.[27]

Dolci became convinced that education was the key to social progress. With the money he received for the Lenin Peace Prize in 1958, he founded the Centro studi e iniziative per la piena occupazione (Center of Research and Initiatives for Full Employment) in Partinico, the village in the Palermo hinterland that had become his home, and other towns on the island.[18][28] In his community work Dolci "sought concrete methods of pedagogy and conflict resolution that would pave the way for a fully democratic and non-violent society."[29]

The centre was one of the most important examples of community development in Italy and especially in the south since World War II. It became both a form of self-organisation of local communities and a training school for a generation of socially and politically committed young people, who found their cohesion as a group and attempted to construct a process of social aggregation through the methods and instruments of active non-violence.

Dolci used the Socratic method, a dialectic method of inquiry, and "popular self-analysis" for empowerment of communities. His pedagogical methods emphasized social awareness and cultural interaction, and won him a worldwide standing. His ideas were taken up by a small but passionate group of supporters that took his methods across Sicily and into mainland Italy.[28]

Harassment campaign against Dolci

editDolci's life and actions stirred ample controversy. He annoyed the authorities, who often actively worked against him. Some of the locals that opposed the Iato river dam were not pleased to see the valleys flooded, and gardens and olive trees ruined.[9] The contractors of the works eventually were either in the Mafia or their middlemen. Dolci was often short of, and careless with, money. He was helped out from time to time, predominantly by English families whose fortunes had been made with the sweet Marsala wine manufactured in Sicily.[1]

In 1964, Palermo archbishop Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini publicly denounced Dolci and Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa, author of The Leopard, as well as the Mafia, for "defaming" all Sicilians. Ruffini's allegations and their approval by Pope Paul VI[30] could be interpreted as a kind of endorsement for his liquidation and increased concerns for Dolci's safety.[31]

In 1968 Dolci was accused of embezzling funds sent from abroad to help the victims of the earthquake which destroyed much of the Belice valley, though the charges were never substantiated.[32] At the same time, some of his followers left to set up their own educational centres accusing him of excessive authoritarianism.[28][32] Some of Dolci's later initiatives were less successful than others, often bordering on the intangible. His centre sought to produce evidence against a secret NATO submarine base around Maddalena island off Sardinia on the basis that such an installation required Italian approval and control which in this case was apparently granted covertly to the United States Navy.[18]

The smears succeeded in pushing Dolci out of the spotlight in Italy. The last 20 years of his life he disappeared from public view, although he continued to be revered abroad, winning prizes for his poetry, and working as a guest lecturer at universities.

Death and legacy

editDolci has been proposed for the Nobel Peace Prize, denounced by the Cardinal Archbishop of Palermo; he has won the support of many communists and some Jesuits, been threatened by the Mafia, and been prosecuted for obscenity by the Italian government for his book Inchiesta a Palermo (Report from Palermo).[33]

He never joined a political party despite several invitations from the Italian Communist Party to run for office. "Reality is very complex", he said. "To understand it, men have tried Christianity, liberalism, Gandhism, socialism. There is some truth in all solutions. We are all mendicants of truth."[33] In the 1970s he rebelled against the state monopoly on broadcasting and set up his own radio station in Partinico in the face of stiff resistance from the police.

Dolci died on December 30, 1997, in Trappeto, from heart failure. He was survived by the five adopted children he had with his first wife, Vincenzina, and by two children from his second marriage. His death triggered a curious mixture of reactions. While the chief antimafia prosecutor in Palermo, Gian Carlo Caselli, said Dolci was one of the people who gave him the keys to do his job, the national press gave him surprisingly short shrift, describing him as a historical curiosity whose work has long since been forgotten.[28]

According to the obituary in The Independent: "If the world now knows anything about the dark, secretive world of the Sicilian Mafia in the first turbulent years after the Second World War, it is largely thanks to Danilo Dolci."[28] The man who in his youth studied architecture became an architect of social change.[18]

For long, he was practically unknown in his native Slovenia. In 2007, however, an exhibition on his life and work was organized in his native town of Sežana. In 2010, a book of his poetry was first translated into Slovene. The same year, a bilingual memorial plaque was placed on his native house, and a local educational organization was named after him.[34] His papers are currently housed at the Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center at Boston University.

Books in English

edit- To Feed the Hungry (1955/1959), London: MacGibbon & Kee.

- Report from Palermo (1959), New York: The Orion Press, Inc.

- The Outlaws of Partinico (1960) London: MacGibbon & Kee

- Sicilian Lives[35] (1960/1981), New York: Pantheon Books.

- Waste (1964), New York: Monthly Review Press

- A New World in the Making (1965) Translated by R. Munroe. Monthly Review Press

- The Man Who Plays Alone (1968), New York: Random House[36]

Biographies

edit- McNeish, James (1965). Fire Under the Ashes: The Life of Danilo Dolci, London: Hodder and Stoughton.[37]

- Mangione, Jerre (1968). A Passion for Sicilians: The World around Danilo Dolci, New York: William Morrow and Co.

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Danilo Dolci, the Gandhi of Sicily, died on December 30th, aged 73", The Economist, January 8, 1998

- ^ a b c "Danilo Dolci", by Frank Walker, in Danilo Dolci nell'accademia del villaggio globale (a cura di Gaetano G. Perlongo), March 1998

- ^ "Nobel Peace Prize nominations". American Friends Service Committee. Archived from the original on 2008-08-15. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- ^ "Jamnalal Bajaj Award". Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation. 2015. Retrieved October 13, 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Salvatore Farina, Remembering Danilo Dolci, in "Sicilia libertaria", n. 449, june 2024, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Danilo Dolci", by Jaclyn Welch, in Danilo Dolci nell'accademia del villaggio globale (a cura di Gaetano G. Perlongo), July 5, 1997

- ^ Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, p. 137

- ^ Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, p. 5

- ^ a b c "Danilo's Dam", Time, September 21, 1962.

- ^ Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, p. 2

- ^ "Dolci v. Far Niente", Time, February 20, 1956

- ^ (in Italian) "In Defence of Daniclo Dolci" Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine, text pronounced by Piero Calamandrei before the Criminal Court of Palermo on March 30, 1956

- ^ "'Apostle Of Poor' Set Free By Sicily", The New York Times, April 1, 1956

- ^ "The Sting of Conscience", Time, April 9, 1956

- ^ a b Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, pp. 18–19

- ^ Sicilians "March in Rome to Ask a Dam", The New York Times, March 13, 1965

- ^ "Sicilians Pledge Strikes To Seek Aid in Quake Area", The New York Times, September 16, 1968

- ^ a b c d "Danilo Dolci – The defiant social activist", by Vincenzo Salerno, Best of Sicily Magazine, April 2004

- ^ Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, p. 164

- ^ a b Bess, Realism, Utopia, and the Mushroom Cloud, pp. 194–97

- ^ (in Italian) "Danilo Dolci e la dimensione utopica", by Livio Ghersi (accessed March 2, 2011)

- ^ "Dolci Is Boycotting Libel Trial In Italy", The New York Times, January 19, 1967

- ^ (in Italian) Ragone, Le parole di Danilo Dolci Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 220–22

- ^ Decision of the Tribunal of Roma, June 21, 1967, published in Il Foro italiano 1968, 342 ff., confirmed by both the Court of Appeals of Rome (July 7, 1972) and the Court of Cassation, VI chamber (June 26, 1973).

- ^ (in Italian) Trent'anni dall'omicidio di Piersanti Mattarella: L'"uomo nuovo" della Democrazia cristiana, asud'europa, January 25, 2010

- ^ (in Italian) Ragone, Le parole di Danilo Dolci Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine, p. 41

- ^ Bess, Realism, Utopia, and the Mushroom Cloud, p. xxiii

- ^ a b c d e "Obituary: Danilo Dolci", The Independent, January 1, 1998

- ^ Bess, Realism, Utopia, and the Mushroom Cloud, p. xxiv

- ^ "Pope Joins Cardinal In Defense Of Sicily", The New York Times, April 26, 1964

- ^ Mangione, A Passion for Sicilians, p. 18

- ^ a b "Danilo Dolci, Vivid Voice Of Sicily's Poor, Dies at 73", The New York Times, December 31, 1997

- ^ a b "From the Slums", Time, January 13, 1958

- ^ (in Slovene) Dolcijeva dvojezična pesniška zbirka "Ne znaš izbirati" Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, Slomedia, November 19, 2010

- ^ "Books of The Times". The New York Times. 31 December 1981.

- ^ The Man Who Plays Alone by Danilo Dolci, The New York Times, April 13, 1969

- ^ "Some Sort of Sicilian Saint", Time, April 8, 1966

Sources

edit- Bess, Michael (1993), Realism, Utopia, and the Mushroom Cloud: Four Activist Intellectuals and Their Strategies for Peace, 1945–1989, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-04421-1

- Mangione, Jerre (1972/1985). A Passion for Sicilians: The World Around Danilo Dolci, New Brunswick: Transaction Books, ISBN 0-88738-606-7

- (in Italian) Ragone, Michele (2011). Le parole di Danilo Dolci, Foggia: Edizioni del Rosone, ISBN 978-88-97220-19-0

- Servadio, Gaia (1976). Mafioso: A History of the Mafia from Its Origins to the Present Day, London: Secker & Warburg ISBN 0-436-44700-2

External links

editMedia related to Danilo Dolci at Wikimedia Commons

- Danilo Dolci nell'accademia del villaggio globale (a cura di Gaetano G. Perlongo)

- Danilo Dolci Papers Archived 2012-03-04 at the Wayback Machine Swarthmore College Peace Collection.