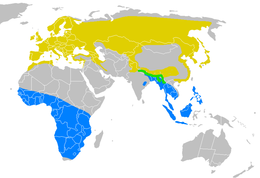

Delichon is a small genus of passerine birds that belongs to the swallow family and contains four species called house martins. These are chunky, bull-headed and short-tailed birds, blackish-blue above with a contrasting white rump, and with white or grey underparts. They have feathering on the toes and tarsi that is characteristic of this genus. The house martins are closely related to other swallows that build mud nests, particularly the Hirundo barn swallows. They breed only in Europe, Asia and the mountains of North Africa. Three species, the common, Siberian and Asian house martins, migrate south in winter, while the Nepal house martin is resident in the Himalayas year-round.

| Delichon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common house martin (Delichon urbicum) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Hirundinidae |

| Subfamily: | Hirundininae |

| Genus: | Delichon F. Moore, 1854 |

| Type species | |

| Delichon nipalense F. Moore, 1854

| |

| Species | |

|

4, see below. | |

| |

| |

The house martins nest in colonies on cliffs or buildings, constructing feather- or grass-lined mud nests. The typical clutch is two or three white eggs; both parents build the nest, incubate the eggs and feed the chicks. These martins are aerial hunters of small insects such as flies and aphids. Despite their flying skills the Delichon martins are sometimes caught by fast-flying birds of prey. They may carry fleas or internal parasites. None of the species are considered threatened, although widespread reductions in common house martin numbers have been reported from central and northern Europe. This decline is due to factors including poor weather, poisoning by agricultural pesticides, lack of mud for nest building and competition with house sparrows for nest sites.

Taxonomy

editThe four Delichon species are members of the swallow family of birds, and are classed as members of the Hirundininae subfamily which comprises all swallows and martins except the very distinctive river martins. DNA studies suggest that there are three major groupings within the Hirundininae, broadly correlating with the type of nest built.[1] The groups are the "core martins" including burrowing species like the sand martin, the "nest-adopters", which are birds like the tree swallow that utilise natural cavities, and the "mud nest builders". The Delichon species construct a closed mud nest and therefore belong to the latter group; they appear to be intermediate between the Hirundo and Ptyonoprogne species that make open cup nests, and the Cecropis and Petrochelidon swallows, which have retort-like closed nests with an entrance tunnel.[2] The genetic evidence suggests a close relationship between Hirundo and Delichon, which is further supported by the frequency of interbreeding between two widespread species, the barn swallow and the common house martin, despite being their being in different genera.[3] The suggested taxonomic sequence of the mud-building swallows has been recommended by at least two European taxonomic committees.[4][5]

The genus Delichon was created by American naturalist Thomas Horsfield and British entomologist Frederic Moore in 1854 to accommodate the Nepal house martin that was first described by Moore in the same year, and is therefore the type species for the genus.[6][7] The two other house martins were moved to Delichon from the genus Chelidon in which they had been placed up to that time.[8] In 2021, the Siberian house martin was split from the common house martin based on morphological and vocal differences.[9][10] The name of the genus, "Delichon", is an anagram of the Ancient Greek term χελιδὡν/chelidôn, meaning swallow.[11]

Species

editThe genus contains four similar species:[9]

| Image | Common name | Scientific name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western house martin | Delichon urbicum | Europe, north Africa and across the Palearctic; winters in sub-Saharan Africa and tropical Asia | |

| Siberian house martin (split from common house martin) |

Delichon lagopodum | Breeds in northeast Asia, winters in east Asia | |

| Asian house martin | Delichon dasypus | Breeds in central and eastern Asia, winters in southeast Asia | |

| Nepal house martin | Delichon nipalense | Northwestern India through Nepal to Myanmar, northern Vietnam, and just into China |

The common and Asian house martins have sometimes been considered to be a single species, although both breed in the western Himalayas without hybridising.[12] There is also limited DNA evidence that suggests a significant genetic distance between these two martins.[13]

Distribution and habitat

editDelichon is an Old World genus with all four species breeding only in the Northern Hemisphere. The common house martin is a widespread migrant breeder across Europe, north Africa and all northern temperate Asia to Kamchatka. It winters in tropical Africa.[14] The Siberian house martin breeds in northeast Russia and winters in southern Asia. The Asian house martin breeds further south than the Siberian house martin in the mountains of central and eastern Asia; its nominate subspecies winters in Southeast Asia,[12] but the races breeding in the Himalayas and Taiwan may just move from the high mountains to lower altitudes.[15] The Nepal house martin is resident in the mountains of southern Asia.[12]

The preferred habitat of the common and Siberian house martins is open country with low vegetation, such as pasture, meadows and farmland, and preferably near water, although it is also found in mountains up to at least 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) altitude. As the name implies, they readily nest on man-made buildings, and will breed even in city centres if the air is clean enough.[14] The other two species favour mountainous country (and sea cliffs in the case of Asian house martin); they use buildings as nest sites less frequently than their northern relative.[16] The wintering grounds of the two migrant species include a range of open country and hilly habitats.[12]

Description

editDelichon martins are 13–15 cm (5–6 in) long, blackish blue above with a contrasting white rump, and with white or grey underparts. They are chunky, bull-headed and short-tailed birds, and have feathering on the toes and tarsi.[17] The common house martin is the largest bird, with an average weight of 18.3 g (0.65 oz), and has the most deeply forked tail; the Nepalese species is the smallest (15 g, 0.53 oz) and has the squarest tail. Distinctive species plumage features are the black chin and black undertail coverts of the Nepal house martin, and the greyish wash to the underparts of the Asian house martin.[12] As with other swallows and martins, the moult is slow and protracted because of the need to maintain efficient flight at all times to enable feeding. Moult normally starts on arrival at the wintering grounds, but overlaps with the breeding season for the non-migratory Nepal house martin.[18]

The Delichon martins have simple flight calls of one to three notes. In the two more widespread species these have a distinctive buzzing quality. The male's song is a short simple ripple, perhaps less musical than that given by other swallows.[12][16]

As a group, the house martins cannot easily be confused with any other swallows. Four species of the genus Tachycineta have white rumps and underparts, but they have bright metallic green or blue-green upperparts, longer tails, and are restricted to Central and South America.[19] The variable plumages of the South Asian species and a confused taxonomic history has left their distribution ranges in doubt.[16]

Behaviour

editBreeding

editThe Delichon martins were originally cliff nesters, breeding in colonies situated under an overhang on a vertical cliff. However, the house martin now largely uses human structures, as, to a lesser extent, does the Asian house martin. The typical nest is a grass or feather-lined deep closed mud bowl with a small opening at the top,[12] but many Asian house martins leave the top of the nest open.[20][21][22]

David Winkler and Frederick Sheldon believe that evolutionary development in the mud-building swallows, and individual species follow this order of construction. A retort builder like red-rumped swallow starts with an open cup, closes it, and then builds the entrance tunnel. Winkler and Sheldon propose that the development of closed nests reduced competition between males for copulations with the females. Since mating occurs inside the nest, the difficulty of access means other males are excluded. This reduction in competition permits the dense breeding colonies typical of the Delichon martins.[2]

The urban common house martin has to compete with house sparrows, which frequently attempt to take over the nest during construction, with the house martins rebuilding elsewhere if the sparrows are successful. The entrance at the top of the completed cup is so small that the sparrows cannot take over the nest once it is finished.[23]

As with other swallows, pairing and copulation displays are normally brief, taking just a few minutes.[18] The male calls to a female and attempts to lead her to the nest, where he lands and continues calling while posing with lowered head, dropped wings and ruffled throat. If he is successful, the female calls and allows him to mount her, usually in the nest. Three or four white eggs are the normal clutch and all three species are frequently double-brooded. Both sexes build the nest, incubate the eggs and feed the chicks, although the female does most of the incubation, which normally lasts 14–16 days. The newly hatched chicks are altricial, and after a further 22–32 days, depending on weather, the chicks leave the nest. The fledged young stay with, and are fed by, the parents for about a week after leaving the nest. Occasionally, young birds from the first brood will assist in feeding the second brood.[12]

A Scottish study showed that mortality in common house martins occurred mostly outside the breeding season and averaged 57%. Females that had raised two clutches in a season had a higher mortality than those that were single-brooded, but there was no such correlation for the males.[24]

Feeding

editThe Delichon species typically feed higher in the air, and take smaller prey than other swallows. It is believed that this reduces inter-specific food competition, particularly with the barn swallow which shares much of the breeding and wintering range of the martins.[23][25][26] The insects eaten are mostly small flies, aphids and Hymenoptera such as winged ants. A wide range of other insects are caught, including Lepidoptera, beetles and lacewings. The Asian house martin appears to occasionally take terrestrial springtails and larvae and the common house martin also sometimes feeds on the ground.[23] These martins are gregarious, feeding in flocks often with other aerial predators like swifts,[12] or other hirundines such as the barn or striated swallows.[27] In the case of at least the common house martin, the start of egg laying appears to be linked to the appearance of large numbers of flying aphids, which provide a stable and abundant food supply.[28]

Predators and parasites

editThe main predators of the house martins are those birds of prey which are capable of catching these agile fliers, such as the hobby.[29] Birds of the Delichon species are most vulnerable when collecting mud from the ground. This has therefore become a communal activity, with a group of these birds descending suddenly on a patch of mud.[30] The usually insectivorous collared falconet has been recorded as hunting Nepal house martins.[31]

The house martins are parasitised by fleas and mites, including the "house martin flea", Ceratophyllus hirundinis and its relatives.[32][33] A Polish study of the common house martin showed that nests typically contained more than 29 species of ectoparasite, with C. hirundinis and another swallow specialist, Oeciacus hirundinis, the most abundant.[34] The genus also hosts endoparasites such as Haemoproteus prognei (avian malaria), which are transmitted by blood-sucking insects including mosquitoes.[35][36][37]

More than 40 beetle species have been recorded in common house martin nests, but most are either typical of the locality or found in the nests of other birds. The typical number of individuals, around 200, is relatively low compared to other bird species (1,400 individual beetles for house sparrow, 2,000 for sand martin). The beetles have no effect on the nesting birds, and the reason for their comparatively low numbers is unknown, although the numbers of specific parasites found in house martin's nests is also quite small.[38]

Conservation status

editThe International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) is the organisation responsible for assessing the conservation status of species. A species is assessed as subject to varying levels of threat if it has a small, fragmented or declining range, or if the total population is less than 10,000 mature individuals, or if numbers have dropped rapidly (by more than 10% in ten years or three generations). None of the Delichon species meets these criteria, and all four house martins are therefore considered of least concern.[39][40][41][42]

The numbers of the two southern Asian species are unknown, but both can be locally abundant, and the Asian house martin is extending its range in southern Siberia.[12][40] The lowland breeding common house martin has greatly benefited from forest clearance, creating the open habitats it prefers, and from human habitation which has given it an abundance of safe man-made nest sites,[12] although widespread declines in its numbers have been reported from central and northern Europe since 1970.[43] This is due to factors including poor weather, poisoning by agricultural pesticides, lack of mud for nest building and competition with house sparrows for nest sites.[12] The formerly conspecific Siberian house martin is also declining. Despite this, the huge geographical range and large numbers of the two northern house martins mean that their global status is secure.[41][42]

Fossil record

editSource:[44]

- Delichon polgardiensis (late Miocene of Polgardi, Hungary)

- Delichon pusillus (Pliocene of Csarnota, Hungary)

- Delichon major (Pliocene of Beremend, Hungary)

Citations

edit- ^ Sheldon, Frederick H; Whittingham, Linda A; Moyle, Robert G; Slikas, Beth; Winkler, David W (2005). "Phylogeny of swallows (Aves: Hirundinidae) estimated from nuclear and mitochondrial DNA". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (1): 254–270. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.11.008. PMID 15737595.

- ^ a b Winkler, David W; Sheldon, Frederick H (1993). "Evolution of nest construction in swallows (Hirundinidae): a molecular phylogenetic perspective". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 90 (12): 5705–5707. Bibcode:1993PNAS...90.5705W. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.12.5705. PMC 46790. PMID 8516319.

- ^ Turner (1989) p. 9

- ^ Sangster, George; Collinson, J Martin; Knox, Alan G; Parkin, David T; Svensson, Lars (January 2010). "Taxonomic recommendations for British birds: Sixth report" (PDF). Ibis. 152 (1): 180–186. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.572.9255. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.2009.00983.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- ^ Sangster, George; van den Berg, Arnoud; van Loon, Andre; Roselaar C S (2009). "Dutch avifaunal list: taxonomic changes in 2004–2008" (PDF). Ardea. 97 (3): 373–381. doi:10.5253/078.097.0314. S2CID 86664358. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 July 2011.

- ^ "ITIS Standard Report Page: Delichon". The Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS). Retrieved 27 December 2009

- ^ Moore, F; Horsfield T (1854). A catalogue of the birds in the museum of the East-India Company, volume 1. London: Wm H Allen & Co. pp. 384–385.

- ^ Dickinson, Edward C.; Dekker, R W R J; Eck, S; Somadikarta, S (2001). "Systematic notes on Asian birds. 14. Types of the Hirundinidae". Zoologische Verhandelingen, Leiden. 335: 138–164.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2021). "Swallows". IOC World Bird List Version 11.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Leader, P.; Carey, G.; Schweizer, M. (2021). "The identification, taxonomy and distribution of Western, Siberian and Asian House Martins". British Birds. 114: 72–96.

- ^ "House Martin Delichon urbicum (Linnaeus, 1758)". Bird facts. British Trust for Ornithology. 16 July 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Turner (1989) pp. 226–233

- ^ Aliabadian, M; Kaboli, M; Nijman V; Vences M (2009). "Molecular identification of birds: Performance of distance-based DNA barcoding in three genes to delimit parapatric species". PLOS ONE. 4 (1): e4119. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4119A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004119. PMC 2612741. PMID 19127298.

- ^ a b Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1066–1069. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- ^ "Yan Yan". Bird list (in Chinese). National Feng Huang Ku Bird Park. Archived from the original on 23 February 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2009

- ^ a b c Rasmussen, Pamela C; Anderton, John C (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. pp. 313–314. ISBN 978-84-87334-67-2.

- ^ Turner (1989) p. 2

- ^ a b Turner (1989) p. 4

- ^ Turner (1989) pp. 102–109

- ^ Durnev, Yu A; Sirokhin I N; Sonin, V D (1983). "Materials to the ecology of Delichon dasypus (Passeriformes, Hirundinidae) on Khamar-Daban (South Baikal Territory)". Zoologicheskii Zhurnal (in Russian). 62 (10): 1541–1546.

- ^ Oates, Eugene W (1890). The Fauna of British India, Including Ceylon and Burma. Birds. Volume 2. London: Tracker, Spink and Co. p. 270.

- ^ Murray, James (1890). The avifauna of British India and its dependencies : a systematic account. London: Trubner and Co. pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b c Coward, Thomas Alfred (1930). The Birds of the British Isles and Their Eggs (two volumes). Vol. 2 (Third ed.). Frederick Warne. pp. 252–254.

- ^ Bryant, D M (1979). "Reproductive costs in the House Martin (Delichon urbica)". Journal of Animal Ecology. 48 (2): 655–675. doi:10.2307/4185. JSTOR 4185. Subscription required

- ^ Turner (1989) p. 18

- ^ Turner (1989) pp. 164–170

- ^ Shrestha, Tej Kumar (2001). Birds of Nepal: v. 2: Field Ecology, Natural History and Conservation. Steven Simpson Natural History Books. pp. 346–347. ISBN 978-0-9524390-9-7.

- ^ Bryant, D M (1975). "Breeding biology of House Martins Delichon urbica in relation to aerial insect abundance". Ibis. 117 (2): 180–216. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1975.tb04206.x.

- ^ Mullarney, Killian; Svensson, Lars; Zetterstrom, Dan; Grant, Peter (1999). Collins Bird Guide. Collins. p. 242. ISBN 978-0-00-219728-1.

- ^ "House Martin Delichon urbicum". BirdGuides. Archived from the original on 8 December 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2007.

- ^ Sivakumar, S; Singha, Hillaljyoti; Prakash, Vibhu (2004). "Notes on the population density and feeding ecology of the Collared Falconet Microhierax caerulescens in Buxa Tiger Reserve, West Bengal, India" (PDF). Forktail. 20: 97–98. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 June 2011.

- ^ Lewis, Robert E (1971). "Descriptions of new fleas from Nepal, with notes on the genus Callopsylla Wagner, 1934 (Siphonaptera: Ceratophyllidae)". Journal of Parasitology. 57 (4): 761–771. doi:10.2307/3277793. JSTOR 3277793. PMID 5105961.

- ^ Rothschild, Miriam; Clay, Theresa (1953). Fleas, Flukes and Cuckoos. A study of bird parasites. London: Collins. pp. 61–62.

- ^ Kaczmarek, S (1993). "Ectoparasites from nests of swallows Delichon urbica and Hirundo rustica collected in autumn". Wiad Parazytol (in Polish). 39 (4): 407–409. PMID 8128730.

- ^ Weisman, Jaime (2007). "Haemoproteus Infection in avian species". University of Georgia. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ Marzal, Alfonso; de Lope, Florentino; Navarro, Carlos; Møller, Anders Pape (2005). "Malarial parasites decrease reproductive success: an experimental study in a passerine bird" (PDF). Oecologia. 142 (4): 541–545. Bibcode:2005Oecol.142..541M. doi:10.1007/s00442-004-1757-2. PMID 15688214. S2CID 18910434. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 December 2009.

- ^ Kim, Kyeong Soon; Yoshio Tsuda; Akio Yamada (2009). "Bloodmeal identification and detection of avian malaria parasite from mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) inhabiting coastal areas of Tokyo Bay, Japan". Journal of Medical Entomology. 46 (5): 1230–1234. doi:10.1603/033.046.0535. PMID 19769059.

- ^ Sustek, Zbyšek; Hokntchova, Daša (1983). "The beetles (Coleoptera) in the nests of Delichon urbica in Slovakia" (PDF). Acta Rerum Naturalium Musei Nationalis Slovaci, Bratislava. XXIX: 119–134. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2012.

- ^ "Nepal House-martin – BirdLife Species Factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 21 December 2021

- ^ a b "Asian House-martin – BirdLife Species Factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 21 December 2021

- ^ a b "Northern House-martin – BirdLife Species Factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 21 December 2021

- ^ a b "Eastern House-martin – BirdLife Species Factsheet". BirdLife International. Retrieved 21 December 2021

- ^ "Population trends". House Martin. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- ^ Kessler, E. (January 2013). "Neogene songbirds (Aves, Passeriformes) from Hungary". Hantkeniana (Budapest), 8: 37-149.

Further reading

edit- Turner, Angela K.; Rose, Chris (1989). A handbook to the swallows and martins of the world. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0-7470-3202-1.