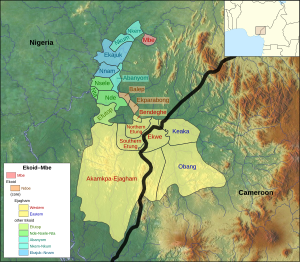

The Ekoid languages are a dialect cluster of Southern Bantoid languages spoken principally in southeastern Nigeria and in adjacent regions of Cameroon. They have long been associated with the Bantu languages, without their status being precisely defined. Crabb (1969)[1] remains the major monograph on these languages, although regrettably, Part II, which was to contain grammatical analyses, was never published. Crabb also reviews the literature on Ekoid up to the date of publication.

| Ekoid | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Southeastern Nigeria, northern Cameroon |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo? |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | ekoi1236 |

| |

The nearby Mbe language is the closest relative of Ekoid[2] and forms with it the Ekoid–Mbe branch of Southern Bantoid.

Languages

editEthnologue lists the following Ekoid varieties with the status of independent languages. Branching is from Watters (1978) and Yoder et al. (2009).

Names and locations (Nigeria)

editBelow is a list of language names, populations, and locations (in Nigeria only) from Blench (2019).[3]

| Language | Cluster | Dialects | Alternate spellings | Own name for language | Endonym(s) | Other names (location-based) | Other names for language | Exonym(s) | Speakers | Location(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakor cluster | Bakor | ||||||||||

| Abanyom | Bakor | Abanyom, Abanyum | Befun, Bofon, Mbofon | 12,500 (1986) | Cross River State, Ikom LGA, main village Abangkang | ||||||

| Efutop | Bakor | Ofutop | Agbaragba | 8,740 (1953), 10,000 (1973 SIL) | Cross River State, Ikom LGA | ||||||

| Ekajuk | Bakor | Akajuk | more than 10,000 (Crabb 1965);[4] 30,000 (1986 Asinya) | Cross River State, Ogoja LGA, Bansara, Nwang, Ntara 1,2 and 3, and Ebanibim towns | |||||||

| Nde–Nsele–Nta cluster | Bakor | 10,000 (1973 SIL) | Cross River State, Ikom LGA | ||||||||

| Nde | Bakor | Ekamtulufu, Mbenkpe, Udom, Mbofon, Befon | 4,000 (1953); est. 12,000 (Asinya 1987)[5] | ||||||||

| Nsele | Bakor | Nselle | 1,000 (1953); est. 3,000 (Asinya 1987) | ||||||||

| Nta | Bakor | Atam, Afunatam | est. 4,500 (Asinya 1987) | ||||||||

| Nkem–Nkum cluster | Bakor | Cross River State, Ogoja LGA | |||||||||

| Nkem | Bakor | Nkim, Ogoja, Ishibori, Isibiri, Ogboja | Nkim | Ogoja | Ishibori | 11,000 (1953); est 18,000 (Asinya 1987) | |||||

| Nkum | Bakor | 5,700 (1953); est. 16,500 (Asinya 1987) | |||||||||

| Nnam | Bakor | Ndem | 1,230 (1953); est. 3,000 (Asinya 1987) | Cross River State, Ikom and Ogoja LGAs | |||||||

| Ejagham cluster | Ejagham | 5 dialects in Nigeria, 4 in Cameroon | Ekoi (Efik name) | 80,000 total: 45,000 in Nigeria, 35,000 in Cameroon (1982 SIL) | Cross River State, Akamkpa, Ikom, Odukpani and Calabar LGAs, and in Cameroon | ||||||

| Bendeghe | Ejagham | Bindege, Bindiga, Dindiga | Mbuma | Cross River State, Ikom LGA | |||||||

| Etung North | Ejagham | Icuatai | 13,900 (1963) | Cross River State, Ikom LGA | |||||||

| Etung South | Ejagham | 4,200 (1963) | Cross River State, Ikom and Akamkpa LGAs | ||||||||

| Ejagham | Ejagham | Ekwe, Ejagam, Akamkpa | Cross River State, Akamkpa LGA and in Cameroon | ||||||||

| Ekin | Ejagham | Qua, Kwa, Aqua | Abakpa | 900 active adult males (1944–45): bilingual in Efik (Cook 1969b) | Cross River State, Odukpani and Calabar LGAs | ||||||

| Ndoe cluster | Ndoe | 3,000 (1953) | Cross River State, Ikom LGA | ||||||||

| Ekparabong | Ndoe | Akparabong | Towns above 2,102 and 310, respectively, (1953) | Akparabong Town, Bendeghe Affi | |||||||

| Balep | Ndoe | Anep, Anyeb | 619 (1953) | Balep and Opu | |||||||

| Mbe | Idum, Ikumtale, Odaje | Mbe | M̀ bè | Ketuen, Mbube (Western) | 9,874 (1963); 14,300 (1973 SIL); 20-30,000 (2008 est.). 7 villages (Bansan, Benkpe, Egbe, Ikumtak, Idibi, Idum, Odajie) | Cross River State, Ogoja LGA |

Phonology

editProto-Ekoid is reconstructed with the following vowels and tones: */i e ɛ a ɔ o u/; high, low, rising, falling, and downstep. The rising and falling tones, though, might be composite.

It is thought to have the following consonants:

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal / Postalveolar |

Velar | Labiovelar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ ~ ŋ | ŋm | |

| Stop / Affricate |

p b | t d | tʃ dʒ | k ɡ | kp ɡb |

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ | ||

| Rhotic | r | ||||

| Approximant | β | l | j | ɣ | w |

[ɲ] occurs at the beginning of a word, and [ŋ] in the middle or at the end.

Study

editThe first publication of Ekoid material is in Clarke (1848)[6] where five ‘dialects’ are listed and a short wordlist of each is given. Other major early publications are Koelle (1854),[7] Thomas (1914)[8] and Johnston (1919–1922).[9] Although Koelle lumped his specimens in the same area, it seems that Cust (1883)[10] was the first to link them together and place them in a group co-ordinate with Bantu but not within it. Thomas (1927)[11] is the first author to make a correct classification of Ekoid Bantu, but oddly the much later Westermann & Bryan (1952)[12] repeats an older, inaccurate classification. This also propagated another old error and included the Nyang languages with Ekoid. Nyang languages have their own quite distinct characteristics and are probably further from Bantu than Ekoid.

Guthrie (1967–1971)[13] could not accept that Ekoid formed part of Bantu. His first improbable explanation was that its ‘Bantuisms’ resulted from speakers of a Bantu language being ‘absorbed’ by those who spoke a ‘Western Sudanic’ language, in other words, the apparent parallels, were simply a massive block of loanwords. This was later modified into ‘Ekoid languages may to some extent share an origin with some of the A zone languages, but they seem to have undergone considerable perturbations’ (Guthrie 1971, II:15). Williamson (1971)[14] in an influential classification of Benue–Congo assigned Ekoid to ‘Wide Bantu’ or what would now be called Bantoid, a rather untidy mass of languages lying somehow between Bantu and the remainder of Benue–Congo.

All modern classifications of Ekoid are based on Crabb (1969) and when Watters (1981)[15] came to explore the proto-phonology of Ekoid, he used this source, rather than his own field material from the Ejagham dialects in Cameroon. A problematic aspect of Crabb is his notation of Ekoid which does not clearly distinguish phonetic from phonemic transcription. Fresh work on Ejagham by Watters (1980,[16] 1981) has extended our knowledge of the Cameroonian dialects of Ekoid. However, an important unpublished dissertation by Asinya (1987)[17] based in fresh fieldwork in Nigeria made an important claim about Ekoid phonology, namely that most Ekoid languages have long/short distinctions in the vowels. Ekoid has raised particular interest among Bantuists because it has a noun-class system that seems close to Bantu and yet it cannot be said to correspond exactly (Watters 1980).

See also

edit- Ekoid word lists (Wiktionary)

References

edit- ^ Crabb, D.W. 1969. Ekoid Bantu Languages of Ogoja. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Ekoid–Mbe". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ^ Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- ^ Crabb, D.W. 1965. Ekoid Bantu languages of Ogoja, Eastern Nigeria, Part 1: Introduction, phonology and comparative vocabulary. West African Language Monographs 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Asinya, O.E. 1987. A reconstruction of the segmental phonology of Bakor (an Ekoid Bantu language). M.A. Thesis, Department of Linguistics, University of Port Harcourt.

- ^ Clarke, John 1848. Specimens of dialects: short vocabularies of languages: and notes of countries and customs in Africa. Berwick-upon-Tweed: Daniel Cameron

- ^ Koelle, S.W. 1854. Polyglotta Africana. London: Church Missionary Society

- ^ Thomas, N.W. 1914. Specimens of languages from Southern Nigeria. London: Harrison & Sons

- ^ Johnston, H.H. 1919-22. A comparative study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu languages. (2 vols.) Oxford: Clarendon Press

- ^ Cust, R.N. 1883. The modern languages of Africa. 2 vols. London: Richard Bentley

- ^ Thomas, N.W. 1927. The Bantu languages of Nigeria. In: Festschrift Meinhof F. Boas et al. eds. 65-73. Hamburg: Friederichsen & Co.

- ^ Westermann, Diedrich & Bryan, M.A. (1970 [1952]). The Languages of West Africa. Oxford: International African Institute / Oxford University Press

- ^ Guthrie, Malcolm 1967-71. Comparative Bantu. 4 vols. Farnham: Gregg International Publishers

- ^ Williamson, K. 1971. The Benue–Congo languages and Ịjọ. Current Trends in Linguistics, 7. ed. T. Sebeok. 245-306. The Hague: Mouton

- ^ Watters, John R. 1981. A phonology and morphology of Ejagham, with notes on dialect variation. Ph.D. thesis. University of California at Los Angeles. xviii, 549 p.

- ^ Watters, John R. 1980. The Ejagam noun class system: Ekoid Bantu revisited. In Larry M. Hyman (ed.), Noun classes in the Grassfields Bantu borderland, 99-137. Southern California Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 8. Los Angeles: University of Southern California

- ^ Asinya, O.E. 1987. A reconstruction of the Segmental phonology of Bakor (an Ekoid Bantu language). M.A. Linguistics, University of Port Harcourt

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY 3.0 license.