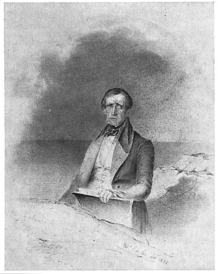

Fitz Henry Lane (born Nathaniel Rogers Lane; also formerly, mistakenly, known as Fitz Hugh Lane;[1] December 19, 1804 – August 14, 1865) was an American painter and printmaker of a style that would later be called Luminism, for its use of pervasive light.

Fitz Henry Lane | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Nathaniel Rogers Lane December 19, 1804 |

| Died | August 14, 1865 (aged 60) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Lithography apprenticeship, Pendleton's Lithography shop in Boston 1832 to 1847 |

| Known for | Marine paintings |

| Style | Luminism |

| Website | fitzhenrylaneonline.org |

Biography

editFitz Henry Lane was born on December 19, 1804, in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Lane was christened Nathaniel Rogers Lane on March 17, 1805, and would remain known as such until he was 27. It was not until March 13, 1832, that the state of Massachusetts would officially grant Lane's own formal request (made in a letter dated December 26, 1831) to change his name from Nathaniel Rogers to Fitz Henry Lane.

As with practically all aspects of Lane's life, the subject of his name is one surrounded by much confusion—it was not until 2005 that historians discovered that they had been wrongly referring to the artist as Fitz Hugh, as opposed to his chosen Fitz Henry.[1] The reasons behind Lane's decision to change his name, and for choosing the name he did, are still unclear; one suggestion is that he did it "to differentiate himself from the well-known miniature painter Nathaniel Rodgers".[2]

From the time of his birth, Lane would be exposed to the sea and maritime life—a factor that obviously had a great impact on his later choice of subject matter. Many circumstances of his young life ensured Lane's constant interaction with various aspects of this maritime life, including the fact that Lane's family lived "upon the periphery of Gloucester Harbor's working waterfront,"[3] and that his father, Jonathan Dennison Lane, was a sailmaker, and quite possibly owned and ran a sail loft. It is often speculated that Lane would most likely have pursued some seafaring career, or become a sail-maker like his father, instead of an artist, had it not been for a lifelong handicap Lane developed as a child. Although the cause cannot be known with certainty, it is thought that the ingestion of some part of the Peru-Apple—a poisonous weed also known as jimsonweed—by Lane at the age of eighteen months caused the paralysis of the legs from which Lane would never recover. Furthermore, it has been suggested by art historian James A. Craig that because he could not play games as the other children did, he was forced to find some other means of amusement, and that in such a pursuit he discovered and was able to develop his talent for drawing.[3] To go a step further, as a result of his having a busy seaport as immediate surroundings, he was able to develop a special skill in depicting the goings-on inherent in such an environment.

Lane could still have become a sail-maker, as such an occupation entailed much time spent sitting and sewing, and that Lane already had some experience sewing from his short-lived apprenticeship in shoe-making. However, as evidenced in this quote from Lane's nephew Edward Lane's "Early Recollections," his interest in art held much sway in his deciding on a career: "Before he became an artist he worked for a short time making shoes, but after a while, seeing that he could draw pictures better than he could make shoes he went to Boston and took lessons in drawing and painting and became a marine artist."[4]

Lane acquired such "lessons" by way of his employment at Pendleton's Lithography shop in Boston, which lasted from 1832 to 1847. With the refinement and development of his artistic skills acquired during his years working as a lithographer, Lane was able to successfully produce marine paintings of high quality, as evidenced in his being listed, officially, as a "marine painter" in the Boston Almanac of 1840. Lane continued to refine his painting style, and consequently, the demand for his marine paintings increased as well.

Lane had visited Gloucester often while living in Boston, and in 1848, he returned permanently. In 1849, Lane began overseeing construction of a house/studio of his own design on Duncan's Point—this house would remain his primary residence to the end of his life. Fitz Henry Lane continued to produce beautiful marine paintings and seascapes into his later years. He died in his home on Duncan's Point on August 14, 1865, and is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery.

Training and influences

editHowever ambiguous many aspects of Lane's life and career may remain, a few things are certain. First, Lane was, even in childhood, clearly gifted in the field of art. As was noted by J. Babson, a local Gloucester historian and contemporary in Lane's time, Lane "showed in boyhood a talent for drawing and painting; but received no instruction in the rules till he went to Boston."[3] In addition to confirming Lane's early talent, this observation also indicates that Lane was largely self-taught in the field of art—more specifically drawing and paintings—previous to beginning his employment at Pendleton's lithography firm at the age of 28. Lane's first-known and recorded work, a watercolor titled The Burning of the Packet Ship "Boston," executed by Lane in 1830, is regarded by many art historians as evidence of Lane's primitive grasp of the finer points of artistic composition previous to his employment at Pendleton's.

Lane may have supplemented his primary, purely experimental practices in drawing and painting with the study of instructional books on drawing, or more likely, by the study of books on the subject of ship design. Some study of the literature on the subject of ship design seems highly plausible, given that Lane would have had easy access to many such texts, and, more importantly, the most certain necessity of such a study in order for Lane to be able to produce works of such accurate detail in realistically depicting a ship as it actually appeared in one of any given number of possible circumstances it faced in traversing the sea.[3]

At the time when Lane began his employment at Pendleton's, it was common practice for aspiring American artists—especially those who, like Lane, could not afford a more formal education in the arts by traveling to Europe or by attending one of the prestigious American art academies, such as New York's National Academy of Design or Philadelphia's Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts—to seek work as a lithographer, this being the next logical step in their pursuit of a career in the arts. As for why such employment was beneficial to the budding artist, art historian James A. Craig, in his book Fitz H. Lane: An Artist's Voyage through Nineteenth-Century America, the most comprehensive account of Lane's life and career, offers this illuminating description of the career evolution of the typical lithographer:

"... an apprentice's schooling presumably began with the graining of stones, the making of lithographic crayons, and the copying of the designs and pictures of others onto limestone. As his talents developed, the apprentice would find himself gradually taking on more challenging tasks, from drafting and composing images (the role of the designer) to ultimately being permitted to draw his own original compositions upon limestone (that most prestigious of ranks within the litho shop, the lithographic artist). Since the compositional techniques employed in lithography differed little from those taught in European academic drawing, and the tonal work so necessary for the process to succeed was akin to that found in painting (indeed, when his studio began in 1825 John Pendleton specifically sought out painters for employment in his establishment due to their habits of thinking in tonal terms), an apprenticeship within a lithographic workshop like Pendleton's in Boston was roughly equivalent to that offered by fine art academies for beginning students."[3]

Working in the lithography shop, Lane would have been taught the stylistic techniques for producing artistic compositions from the practiced seniors among his fellow employees. As noted above, because Pendleton specifically sought painters to work in his shop, Lane would most likely have received the benefit of working under and with some of the most skilled aspiring and established marine and landscape painters of his day. The English maritime painter Robert Salmon, who, historians have discovered, came to work at Pendleton's at a period coinciding with Lane's employment therein, is regarded as having had a large impact, stylistically, on Lane's early works.

Beginning in the early 1840s Lane would declare himself publicly to be a marine painter while simultaneously continuing his career as a lithographer. He quickly attained an eager and enthusiastic patronage from several of the leading merchants and mariners in Boston, New York, and his native Gloucester. Lane's career would ultimately find him painting harbor and ship portraits, along with the occasional purely pastoral scene, up and down the eastern seaboard of the United States, from as far north as the Penobscot Bay/Mount Desert Island region of Maine, to as far south as San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Style

editFrom one of his first copied lithographs, View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass (1836), to his very last works, Lane would incorporate many of the following arrangements and techniques consistently in the composition of his art works, both his lithographs and paintings:

- Nautical subject matter

- Depiction of various naval craft in highly accurate detail

- An overall extensive amount of detail

- The distinctive expanse of sky

- Pronounced attention to depicting the interplay of light and dark

- Hyper-accentuated vegetation within the immediate foreground

- An elevated "insider point of view" perspective[3]

Perhaps most characteristic element of Lane's paintings is the incredible amount of attention paid to detail—probably due in part to his lithographic training, as the specific style of lithography that was popular at the time of his training was characterized by the goal of verisimilitude.

In terms of Lane's influences and relations to the artistic tradition of Luminism, Barbara Novak, in her book "American Painting in the Nineteenth Century", relates Lane's later works to Ralph Waldo Emerson's Transcendentalism (which she relates directly to the emergence of Luminism), claiming that "[Lane] was the most 'transparent eyeball",[5] and that this was evidenced by Lane's balancing of what Novak describes as the "contributions of the primitive and the graphic traditions to his art",[5] the primitive being what he learned on his own by first observing and interacting with the surrounding environment he sought to depict, and the graphic being those skills Lane acquired through working as a lithographer. This balance does indeed seem to support the connection of Lane's works with Luminism, as one definition of luminist art is that "characterized by a heightened perception of reality carefully organized and controlled by principles of design. As one of the styles of landscape painting to emerge in the nineteenth century, luminism embraced the contemporary preoccupation with nature as a manifestation of God's grand plan. It was luminism more than any other of the schools that succeeded in imbuing an objective study of nature with a depth of feeling. This was accomplished through a genuine love and understanding of the elements of nature—discernible in the intimate arrangement of leaves on a bough—and their arrangement to reveal the poetry inherent in a given scene."[6]

Legacy

editOther findings have shed new light onto not only Lane's artistic process but have also revealed him to have been a staunch social reformer, particularly within the American temperance movement. As well, the long-held suspicion that Lane was a transcendentalist has been confirmed, and it has been uncovered that he was also a Spiritualist. Sensational claims that Lane was "a somewhat saddened and introspective figure … often prone to moodiness with friends",[7] and that his existence was one of "quiet loneliness",[8] have been proven fallacious with the full quotation of the testimony of John Trask, a patron, friend, and next door neighbor of the artist, who states that Lane "was always hard at work and had no moods in his work. Always pleasant and genial with visitors. He was unmarried having had no romance. He was always a favorite and full of fun. He liked evening parties and was fond of getting up tableaux."[9]

Long believed to have given instruction to only one artist during his career—a local lady of limited artistic abilities named Mary Mellen—it has now been established that Lane was the instructor and mentor to several other artists, most importantly Benjamin Champney and America's other great 19th century marine painter, William Bradford.

A contemporary of the Hudson River School, he enjoyed a reputation as America's premier painter of marine subjects during his lifetime, but fell into obscurity soon after his death with the rise of French Impressionism. Lane's work would be rediscovered in the 1930s by the art collector Maxim Karolik, after which his art steadily grew in popularity among private collectors and public institutions. His work can now command at auction prices ranging as high as three to five million dollars.

The largest collection of his work is currently held by the Wallace Family of Boston, Massachusetts where his work is on display throughout their family offices, private homes, and estates.

Artworks

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| Lane's Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine, Smarthistory[10] |

- The Burning of the Packet Ship "Boston", 1830, watercolor, view Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine

- View of the Town of Gloucester, Mass, 1836, lithograph, view

- Steamer Brittania in a Gale, 1842, oil on canvas, Boston, view

- Gloucester Harbor from Rocky Neck, 1844, Cape Ann Museum Collection, view

- St. Johns, Porto Rico, ca 1850, The Mariners' Museum, view

- Gloucester Inner Harbor, 1850, The Mariners' Museum view

- The Fishing Party, 1850, view

- The Golden State Entering New York Harbor, 1854, oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Stage Rocks and Western Shore of Gloucester Outer Harbor, 1857, oil on canvas, John Wilmerding Collection, view

- Ship in Fog, Gloucester Harbor, ca. 1860, Princeton University Art Museum

- The Western Shore with Norman's Woe, 1862, Cape Ann Museum Collection, view

- Stage Fort across Gloucester Harbor, 1862, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, view

- Gloucester Harbor at Sunrise, 1863, Cape Ann Museum Collection, view

- Clipper Ship "Sweepstakes", 1853, Museum of the City of New York Collection, view

- Ships Passing in Rough Seas, 1856, Private Collection, view

- Lumber Schooners at Evening in Penobscot Bay, 1860, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC view

- View of Coffin's Beach, 1862, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, view

- El fuerte y la isla Ten Pound, Gloucester, Massachusetts, 1847, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, view

- Boston Harbor- Boston Museum of Fine Arts

- Boston Harbor, 1856, oil on canvas, Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas, http://www.cartermuseum.org/artworks/254

Exhibitions

edit- "American Masters from Bingham to Eakins: The John Wilmerding Collection", The National Gallery of Art, May 9 – October 10, 2004

- "Works of Fitz Henry Lane", Cape Ann Museum, Permanent Collection (this is also the largest collection of Lane paintings in the world) [1]

- "Coming of Age: American, 1850s to 1950s". Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts (September 9, 2006 – January 7, 2007); Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (March 14 – June 8, 2008); Meadows Museum of Art, Dallas (November 30 – February 24, 2008); Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice (June 27 – October 12, 2008)

References

edit- ^ a b McCarthy, Gail, "Oh Henry, Fitz Hugh Lane by Another Name" (subscription required) / free trial, The Ellsworth American (Maine), March 2, 2006. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ "$5.5 Million Dollar World Record | Fitz Henry Lane Painting | Skinner Inc". www.skinnerinc.com. Retrieved 2015-11-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Craig, James. Fitz H. Lane: An Artist's Voyage Through Nineteenth-Century America. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. p. 17

- ^ Gerdts, William H.; C. C. ""The Sea Is His Home": Clarence Cook Visits Fitz Hugh Lane". American Art Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3. (Summer, 1985), pp. 44–49.

- ^ a b Novak, Barbara. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1969, p. 110

- ^ Wilmerding, John. American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850–1875. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1980.

- ^ Wilmerding, John: Fitz Hugh Lane. Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1971, p. 20

- ^ Wilmerding, John: Fitz Hugh Lane. Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1971, p. 39

- ^ Trask, John: Notes on the life of Fitz Henry Lane as given by John Trask of Gloucester to Emma Todd (now Mrs. Howard P. Elwell) about 1885. Collection of the Cape Ann Historical Association

- ^ "Lane's Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

Sources

edit- Fitz Henry Lane at the Cape Ann Museum which has the largest collection of his work (40 paintings and 100 drawings).

- Craig, James. Fitz H. Lane: An Artist's Voyage Through Nineteenth-Century America. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2006. ISBN 1-59629-090-0.

- Mary Foley. "Fitz Hugh Lane, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and the Gloucester Lyceum." American Art Journal, Vol. 27, no. 1/2, 1995/1996

- Gerdts, William H.; C. C. "'The Sea Is His Home': Clarence Cook Visits Fitz Hugh Lane." American Art Journal, Vol. 17, No. 3. (Summer, 1985), pp. 44–49.

- Howat, John K.; Sharp, Lewis I.; Salinger, Margaretta M. "American Paintings and Sculpture." Notable Acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art), No. 1975/1979. (1975–1979), pp. 64–67.

- Novak, Barbara. American Painting of the Nineteenth Century. New York: Praeger Publishers, Inc., 1969.

- Sharp, Lewis I. "American Paintings and Sculpture." Notable Acquisitions (Metropolitan Museum of Art), No. 1965/1975. (1965–1975), pp. 11–19.

- Smith, Gayle L."Emerson and the Luminist Painters: A Study of Their Styles" American Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 2. (Summer, 1985), pp. 193–215.

- Troyen, Carol. The Boston Tradition. New York: The American Federation of Arts, 1980.

- Wilmerding, John. The Genius of American Painting. New York: William Morrow & Company, Inc., 1973.

- Wilmerding, John. "Fitz Hugh Lane: Imitations and Attributions." American Art Journal, Vol. 3, No. 2. (Autumn, 1971), pp. 32–40.

- Wilmerding, John. American Light: The Luminist Movement, 1850–1875. Washington DC: National Gallery of Art, 1980.

External links

edit- Fitz Henry Lane: An online project under the direction of the CAPE ANN MUSEUM Gloucester, Massachusetts

- Museo Thyssen Bornemisza Biography and Works: Fitz Henry Lane

- Art and the Empire City: New York, 1825-1861, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Lane (see index)