William Floyd Collins (July 20, 1887[a] – c. February 13, 1925) was an American cave explorer, principally in a region of Kentucky that houses hundreds of miles of interconnected caves, today a part of Mammoth Cave National Park, the longest known cave system in the world.

Floyd Collins | |

|---|---|

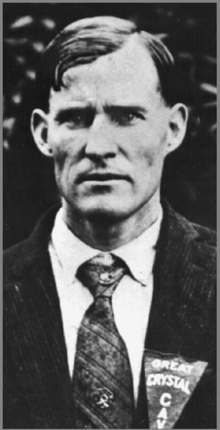

Collins in Cave City circa 1924 | |

| Born | William Floyd Collins July 20, 1887[a] Auburn, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | c. February 13, 1925 (aged 37) Cave City, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky |

| Known for | Cave exploration in Central Kentucky; being trapped in Sand Cave and dying before a rescue party could get to him |

During the early 20th century, in an era known as the Kentucky Cave Wars,[1] spelunkers and property owners entered into bitter competition to exploit the bounty of caves for commercial profit from tourists, who paid to see the caves. In 1917 and 1918, Collins discovered and commercialized Great Crystal Cave in the Flint Ridge Cave System, but the cave was remote and visitors were few. Collins had an ambition to find another cave he could open to the public closer to the main roads, and entered into an agreement with a neighbor to open up Sand Cave, a small cave on the neighbor's property.

On January 30, 1925, while working to enlarge the small passage in Sand Cave, Collins became trapped in a narrow crawlway 55 feet (17 m) below ground. The rescue operation to save him became a national media sensation and one of the first major news stories to be reported using the new technology of broadcast radio. After four days, during which rescuers were able to bring water and food to Collins, a rock collapse in the cave closed the entrance passageway, stranding him inside, except for voice contact, for another 10 days. Collins died of thirst and hunger, compounded by exposure through hypothermia after being isolated for a total of 14 days, three days before a rescue shaft reached his position. Collins' body was recovered two months later.

Although Collins was unknown publicly for most of his lifetime, the fame he gained from the rescue efforts and his death resulted in him being memorialized on his tombstone as the "Greatest Cave Explorer Ever Known".[2]

Early life

editWilliam Floyd Collins was born on July 20, 1887,[a] the son of Leonidas "Lee" Collins (1858–1936) and Martha Jane (née Burnett) (1862–1915). The Collins family had already suffered hardship prior to Floyd's death in 1925, as his mother Martha died from tuberculosis in 1915, and his older brother James Collins had died in 1922 from Typhoid fever. Floyd's siblings included Homer Collins (1902–1969), Nellie Collins (1900–1970), and Marshal (1897–1981), Anna, and Andy Collins. After the death of his mother, Floyd's father remarried to Serilda Jane "Miss Jane" (née Tapscott), who was the widow of a caver who died in 1915. Miss Jane died in 1926, just a year after Floyd, after which Lee remarried for a third time.[4]

Floyd Collins was born on the Collins family farm, located approximately 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Mammoth Cave near the Green River in Kentucky. Floyd began entering caves by himself at the age of six in search of Native American artifacts to sell to tourists at the Mammoth Cave Hotel.[5] In 1910 Floyd discovered his first cave, Donkey's Cave, on the Collins farm. In 1912, Edmund Turner, a geologist, hired Floyd to show him caves of the region. Consequently, Turner and Floyd assisted with the discovery of Dossey's Dome Cave in 1912 and Great Onyx Cave in 1915.[6]

Great Crystal Cave

editIn September 1917, while climbing up a bluff on the Collins farm, Floyd noticed cool air coming from a hole in the ground. Upon widening the hole, he was able to drop down into a cavity that was part of a passage blocked by breakdown.[7] In December 1917, after further excavation of the breakdown, Floyd discovered the sinkhole entrance to what he would later name "Great Crystal Cave."[6] Lee Collins deeded Floyd a half interest in the cave, and they immediately decided to commercialize it.[8] After tremendous preparation by the entire family, the transformed show cave was opened to tourists in April 1918. However, the cave attracted a low number of tourists due to its remote location.[9]

Sand Cave – 1925 incident

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2017) |

Collins' initial venture and entrapment

editCollins hoped to find either another entrance to the Mammoth Cave or an unknown cave along the road to Mammoth Cave in order to draw more visitors and reap greater profits. He made an agreement with three farmers who owned land closer to the main highway. If he found a cave, they would form a business partnership and share in the responsibilities of operating the ensuing tourist attraction. Working alone, Collins explored and expanded a hole within three weeks that would later be called "Sand Cave" by the news media. Collins managed to squeeze through several narrow passageways, one of which was reported as being no larger than 9" tall, and claimed he had discovered a large grotto chamber, though its existence was never verified. He worked on creating a more practical entrance to the grotto for several hours a day and weeks on end in order to make it more accessible to tourists. On January 30, 1925, after several hours of work, his gas lamp began to dim. He attempted to leave the passage quickly, before losing all light to the chamber, but became trapped in a small passage on his way out. Collins accidentally knocked over his lamp, putting out the light, leading to misplacement of his foot on what seemed to be a stable wall of the cave. The passage shifted, and he was caught by a 26.5-pound (12.0 kg) rock that fell from the cave ceiling, pinning his left leg; additionally, torrents of loose gravel fell and completely buried his body. He was trapped 150 feet (46 m) from the entrance.

Discovery and rescue efforts

editNeighbors began to worry for Floyd the next day, and sought out to find him. Though none of them were brave enough to take on the smaller passages it took to reach Collins, they were able to get close enough to communicate with him and learn he was trapped. His younger brother Homer was soon phoned to the scene, and was the only person able to make it through the small passages to get to Floyd before reporter Skeets Miller, Lieutenant Robert Burdon of the Louisville Fire Department, and family friend Johnnie Gerald crossed the boundary in the coming days. Homer brought Floyd food and liquids to retain his energy, and many ideas were thought up by locals and tourists alike as techniques to get Floyd out of the cave. On February 2, 1925, a plan was devised to hoist Collins from the cave using a harness, rope, and the strength of multiple men. This attempt failed and it injured Collins, pulling his torso directly upwards and against the ceiling of rock above him. Rescuers ultimately decided the best way to get him out was to dig out each rock that surrounded him and leverage the large rock off his foot.

Eventually, an electric light was run down the passage to provide him lighting and some warmth. Due to the attention the disaster gained, hundreds of inexperienced cave explorers and tourists stood outside the mouth of the cave. The cool winter air caused them to light campfires that disrupted the natural ice within Sand Cave, causing it to melt and create puddles of cool water; one of which Floyd himself lay in. On February 4, the cave passage collapsed in two places due to the ice melting. Attempts were made to dig the passages that led to Floyd back out, but rescue leaders, led by Henry St. George Tucker Carmichael, determined the cave impassable and too dangerous, which brought the decision to dig a shaft straight down to reach the chamber behind Collins.[10] Collins survived for more than a week while rescue efforts were organized. The cave drew air inward, meaning no menchanical equipment could be used to dig into the cave, as it was feared that the fumes would suffocate Collins in the process. A 55-foot (17 m) shaft would have to be dug downwards with nothing but pickaxes and shovels. It was estimated that the team of 75 volunteer workers would be able to dig this shaft within 30 hours, at a rate of 2 feet (0.61 m) per hour. The first ton of dirt moved efficiently, though around 10 feet (3.0 m), the shaft became so narrow only two men could work at a time. By 15 feet (4.6 m), workers hit boulders under the surface and began to use pickaxes. A series of pulley systems were used to remove rocks from the hole, but the pace of work slowed as they dug nearer to Collins. A radio amplifier had been jerry-rigged to the copper wire that connected Collins's light bulb. A scientist believed the amplifier could detect vibrations whenever Collins moved. The amplifier crackled 20 times every minute, a hopeful sign that Collins might be breathing.

Collins' death

editOn February 11, 1925, tests showed that Collins' light bulb had gone out, meaning there was no way to tell if he was still alive. The 55-foot (17 m) shaft and subsequent lateral tunnel intersected the cave just above Collins, but when he was finally reached on Monday, February 16, by miner Ed Brenner, he was "cold and apparently dead."[11][6] Having been appointed as the members of a coroner's jury, Floyd's friend, Johnnie Gerald, and a few other acquaintances of Floyd were allowed to go into the lateral tunnel and positively identify the body. Dr. William Hazlett and Captain C.E. Francis, a National Guard medical officer, were then unsuccessful in an attempt to reach the body, but Brenner went in front of them to the body and was able to follow their examination instructions for the official death declaration to be made.[11] It was estimated Floyd had been dead for three to five days,[6] with February 13 being the most likely date of death.[12]

Media attention

editNewspaper reporter William Burke "Skeets" Miller from The Courier-Journal in Louisville reported on the rescue efforts from the scene. Miller, of small stature, was able to remove a lot of earth from around Collins. He also interviewed Collins in the cave, receiving a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage[13] and playing a part in Collins' attempted rescue. Miller's reports were distributed by telegraph and were printed by newspapers across the country and abroad, and the rescue attempts were followed by regular news bulletins on the new medium of broadcast radio (the first broadcast radio station KDKA having been established in 1920). Shortly after the media arrived, the publicity drew crowds of tourists to the site, at one point numbering in the tens of thousands. Collins' neighbors sold hamburgers for 25 cents. Other vendors set up stands to sell food and souvenirs, creating a circus-like atmosphere. The Sand Cave rescue attempt grew to become the third-biggest media event between the world wars. (The biggest media events of that time both involved Charles Lindbergh—the trans-Atlantic flight and his son's kidnapping—and Lindbergh actually had a minor role in the Sand Cave rescue, too, having been hired to fly photographic negatives from the scene for a newspaper.)[13] Since the nearest telegraph station was in Cave City, some miles from the cave, two amateur radio operators with the callsigns 9BRK and 9CHG provided the link to pass messages to the authorities and the press.[14]

Burials and exhibition of body

editWith Collins's body remaining in the cave, funeral services were held on the surface. Homer Collins was not pleased with Sand Cave as his brother's grave, and two months later, he and some friends reopened the shaft. They dug a new tunnel to the opposite side of the cave passage and recovered Floyd Collins' remains on April 23, 1925.[13] The body was taken that day to Cave City for embalming at J.T. Geralds and Brothers funeral home. Following a 2-day visitation at the funeral home, on April 26, 1925, his body was transported to the Collins family farm[6] and buried on the hillside over Great Crystal Cave,[15] which Lee Collins renamed "Floyd Collins' Crystal Cave." In 1927, Lee Collins sold the homestead and cave to Dr. Harry Thomas, dentist and owner of Mammoth Onyx Cave and Hidden River Cave.[6] The new owner placed Collins' body in a glass-topped coffin and exhibited it in Crystal Cave for many years.[13][16] On the night of March 18–19, 1929, the body was stolen. The body was later recovered, having been found in a nearby field, but the injured left leg was missing.[13][16] After this desecration, the remains were kept in a secluded portion of Crystal Cave in a chained casket. In 1961, Crystal Cave was purchased by Mammoth Cave National Park and closed to the public.[16] The Collins family had objected to Collins' body being displayed in the cave and, at their request, the National Park Service re-interred him at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, Mammoth Cave, Kentucky in 1989.[13][16] It took a team of 15 men three days to remove the casket and tombstone from the cave.

Legacy

editThe story is referenced in the 1951 film Ace in the Hole starring Kirk Douglas.

Author Sharyn McCrumb wrote about this event in "The Devil Amongst the Lawyers."

Collins' life and death inspired the musical Floyd Collins by Adam Guettel and Tina Landau,[17] as well as one film documentary, several books, a museum and many short songs.

In 2006, actor Billy Bob Thornton optioned the film rights to Trapped! The Story of Floyd Collins and a screenplay was adapted by Thornton's writing partner, Tom Epperson. However, Thornton's option expired and the film rights were acquired by producer Peter R. J. Deyell in 2011.[18]

Fiddlin' John Carson and Vernon Dalhart recorded "The Death of Floyd Collins" in 1925.[19]

See also

edit- Moose River Disaster, mine cave-in covered extensively on radio in 1936

Notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "Cave Wars - Mammoth Cave National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved January 2, 2017.

- ^ Murray & Brucker (2013), p. 235.

- ^ Murray & Brucker (2013), p. 306.

- ^ Murray & Brucker (2013), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Collins & Lehrberger (2005), p. 20.

- ^ a b c d e f Benton, John; Napper, Bill; Thompson, Bob (2017). The Floyd Collins Tragedy at Sand Cave. Images of America. San Francisco: Arcadia. ISBN 978-1-4396-5950-2. [page needed]

- ^ Collins & Lehrberger (2005), pp. 69–71.

- ^ Collins & Lehrberger (2005), p. 81.

- ^ Collins & Lehrberger (2005), pp. 87–88.

- ^ "Cave floor expands and entombs Collins". Journal and Courier. February 5, 1925. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Collins & Lehrberger (2005), p. 196.

- ^ Murray & Brucker (2013), p. 213.

- ^ a b c d e f Bukro, Casey (March 26, 1989). "Folk hero's burial ends 3 generations of anguish". Chicago Tribune. p. 19. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ DeSotto, Clinton: 200 Meters & Down - The Story of Amateur Radio, 1936 - American Radio relay League p.162 ISBN 978-0-87259-001-4

- ^ Collins & Lehrberger (2005), p. 201.

- ^ a b c d Bukro, Casey (March 26, 1989). "Folk hero's burial ends 3 generations of anguish 2". Chicago Tribune. p. 20. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Blackfriars goes underground for new musical". Democrat and Chronicle. May 3, 2002. p. 19. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Floyd Collins Book Acquired by Producer Peter R.J. Deyell". Broadway World. April 26, 2011. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved June 26, 2011.

- ^ "The Death of Floyd Collins (Edison Blue Amberol: 5049)". 1925. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

Works cited

edit- Collins, Homer; (as told to) Lehrberger, John (2005). The Life and Death of Floyd Collins. St. Louis: Cave Books. ISBN 0-939748-47-9.

- Murray, Robert K.; Brucker, Roger W. (2013). Trapped!: The Story of Floyd Collins (Revised ed.). The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-0153-8. JSTOR j.ctt2jcn55.1. Project MUSE book 22127. [First edition: Trapped!: The story of the struggle to rescue Floyd Collins from a Kentucky cave in 1925, an ordeal that became one of the most sensational news events of modern times. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. 1979. ISBN 0-399-12373-3.]

Further reading

edit- Lesy, Michael (October 1976). "Dark Carnival: The Death and Transfiguration of Floyd Collins". American Heritage. Vol. 27, no. 6. pp. 34–45.

- Reilly, Lucas (July 13, 2018). "The 1925 Cave Rescue That Captivated the Nation". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on December 3, 2023.