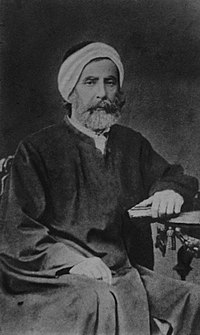

Hoxhë Hasan Tahsini or simply Hoxha Tahsim (7 April 1811 – 3 July 1881)[1] was an Albanian alim, astronomer, mathematician and philosopher. He was the first rector of Istanbul University[2] and one of the founders of the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights. Tahsini is regarded as one of the most prominent scholars of the Ottoman Empire of the 19th century.[3]

Hasan Tahsini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 April 1811 |

| Died | 3 July 1881 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | Albanian |

| Citizenship | Ottoman |

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | astronomy, psychology |

| Signature | |

| |

Early life

editHasan Tahsini was born in 1811 in the village of Ninat, Konispol, then part of the Ottoman Empire. His father Osman Efendi Rushiti was a member of the ulama. When he was young he worked as tutor to the sons of Hayrullah Efendi, Minister of Education of the Ottoman Empire. Hayrullah Efendi later appointed Tahsini to the staff of the Ottoman school of Paris, where Tahsini taught Turkish and religious sciences, while also being the imam of the Ottoman embassy and a student of mathematics and natural sciences at the University of Paris.[4] He studied in Paris for twelve years after being sent there by Resid Pasha, who was trying to create a Westernized ulama elite. In 1869 Tahsini returned in the Ottoman Empire to accompany the body of Fuad Pasha who had died in Nice. His brother is Ferik Hoxha, his nephew is Xhaferr Hoxha, the father of Bilal Xhaferi.

Istanbul University

editIn 1870 he became the first rector of the newly established Istanbul University, where he gave lectures on physics, astronomy and psychology. The government appointed Tahsini as rector as it was believed that he could establish a balance between western European and Islamic methods and ideologies.[5] However, at that time Tahsini's scientific research and unreserved liberalism led to him being frequently attacked by conservative ulama circles[4] The attacks against Tahsini began when he conducted experiments in order to illustrate the notion of vacuum to his students.[6] Tahsini placed a pigeon underneath a glass bell, emptied the receptacle and the pigeon eventually suffocated proving Tahsini's theory. The conservative circles considered Tahsini's experiment as evidence of witchcraft and performance of magic.[6] After the experiment he was declared a heretic through a fatwa, dismissed from the university, and disallowed to give lectures.[6] The university was also closed for a period because Jamal-al-Din Afghani, another professor influenced by Tahsini, supported his theories.[6]

Works

editTahsini wrote the first Turkish language treatise on psychology titled Psychology or the Science of Soul, a work influenced by modernism and the first book whose title contained the word psychology.[4][7][2] He also wrote the first Turkish-language book on modern astronomy being also the first popular science book in Turkish.[4] Other works of Tahsini in the Turkish language include a translation of Constantin François de Chassebœuf's Loi Naturelle.[4]

Tahsini was a prominent member of the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights established in Istanbul, 1877.[8] The Committee for Defending Albanian Rights appointed Tahsini along with Sami Frashëri, Pashko Vasa and Jani Vreto to create an Albanian alphabet which by 19 March 1879 the group approved Frashëri's 36 letter alphabet consisting mostly of Latin characters.[9] Tahsini during the process had worked with Sami Frasheri, one of the most important figures of the Albanian National Awakening to develop a unique alphabet of the Albanian language.[2][10] According to Tahsini the alphabet was developed in such way that each letter required the least hand movements to be written.

Sources

edit- ^ "Hasan Tahsini, arduo sostenitore dell'indipendenza e della lingua albanese". Radio Tirana International (in Italian). 3 April 2018. Archived from the original on 18 August 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ a b c Gawrych 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Tziovas, Demetres (2003). Greece and the Balkans: identities, perceptions and cultural encounters since the Enlightenment. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 0-7546-0998-7.

- ^ a b c d e Keddie, Nikki (1972). Scholars, saints, and Sufis: Muslim religious institutions in the Middle East since 1500. University of California Press. p. 39. ISBN 0-520-02027-8.

- ^ İhsanoğlu, Ekmeleddin (April 2004). Science, technology, and learning in the Ottoman Empire: Western influence, local institutions, and the transfer of knowledge. Ashgate/Variorum. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-86078-924-6. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d Mardin, Şerif (2000). The genesis of young Ottoman thought: a study in the modernization of Turkish political ideas. Syracuse University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0-8156-2861-7.

- ^ Shouksmith, George (1990). Psychology in Asia and the Pacific: status reports on teaching and research in eleven countries. Unesco Principal Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. p. 10. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (January 2006). Albanian literature: a short history. I. B.Tauris & Company, Limited. pp. 75–76. ISBN 1-84511-031-5. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 59. ISBN 9781845112875. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Skendi, Stavro (1967). The Albanian national awakening. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9781400847761. Archived from the original on 2 July 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2022.