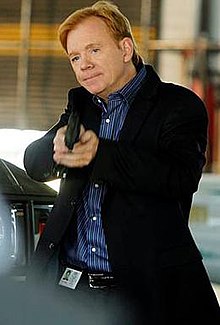

Horatio "H" Caine is a fictional character and the protagonist of the American crime drama CSI: Miami, portrayed by David Caruso from 2002 to 2012.[1] He is the head of the crime lab, under the rank of Lieutenant of the Miami-Dade Police Department (MDPD).

| Horatio Caine | |

|---|---|

| CSI: Miami character | |

| |

| First appearance | CSI May 9, 2002 (2x22, "Cross Jurisdictions")[a] |

| Last appearance | CSI: Miami April 8, 2012 (10x19, "Habeas Corpse") |

| Portrayed by | David Caruso |

| City | Miami |

| In-universe information | |

| Full name | Horatio Caine |

| Alias | John Kelly (undercover name) |

| Nickname | H |

| Occupation | Police Lieutenant |

| Significant other | Marisol Delko (wife; deceased) Julia Winston |

| Children | Kyle Harmon (son) |

| Position | Crime Scene Investigator |

| Rank | Director of the Miami Crime Laboratory |

| Other Appearances | CSI (2) CSI: NY (2) |

Character development

editDavid Caruso previously played Detective John Kelly in NYPD Blue.[2][3] Robert Bianco, in a review of "Golden Parachute" for USA Today, writes that "[w]hat hasn't changed [from NYPD Blue] is [Caruso's] ability to infuse every line and moment with so much honesty and quiet intensity that you're unable to look away."[4] Charles McGrath also notes "some carry-over intensity" from the earlier role, in a review of the CSI franchise for The New York Times.[2] The series co-creator Ann Donahue states that Caruso embues the character with a mixture of "manliness and humanity".[5] In reference to Caruso's earlier role, the CSI: Miami sixth season premiere "Dangerous Son" reveals Horatio Caine to have gone undercover as "John Kelly" in New York the early 1990s (retroactively indicating John Kelly and Horatio Caine to be the same character), conceiving a long-lost son, Kyle Harmon, with Julia Winston.

Caruso has been described as "intricately involved" with establishing the diction and stance of Horatio Caine.[3]

Reception and critical analysis

editThe character of Horatio Caine was popular with viewers, especially women, coming to be regarded as a sex symbol.[3] Maria Elena Fernandez, writing in the Los Angeles Times, describes Caine as "serious and compassionate" and "[c]ampy and melodramatic".[3] Charles McGrath describes Caine's focus on crime solving as "so passionate and so cynical", adding that the character sometimes appears "slightly deranged".[2] Caryn James, in a review of "Golden Parachute" for the New York Times, describes the character's "calm intensity...as if Caine barely holds his explosive investigations together under the blazing sun."[6] David Stubbs, writing in The Guardian, comments that the character's "habit of hitching his sunglasses and delivering deadpan one-liners has attracted devotion and derision in equal measure."[7] Amanda Hess, for example, mocks the sunglasses trope in the New York Times, calling Caruso "the most dedicated modern practitioner of glasses business".[8] On an episode of the Late Show with David Letterman that aired on March 8, 2007, comedian Jim Carrey professed to being a fan of the show and went on to give a satirical impersonation of Caine, which Caruso described as "amazing, astonishing."[9]

Patrick West describes the character as representing "a reaction against the globalized multi-nationalism, multi-racism and multi-ethnicities of Miami"; he dissects Caine's actions in "Identity" (where he arrests Clavo Cruz after demolishing his claim to diplomatic immunity), considering that the character "effectively restabilizes American identity within melting pot Miami".[10] West comments that Caine is often filmed in a disorientating fashion, with rapid cuts to very close-range shots, with the character "embedded uncomfortably within the architecture, rather than being in control of his spatial surroundings."[10] According to West, Cher Coad considers that the character's habitual "hunched posture" may represent him being "weighed down by the architecture".[10]

West goes on to highlight Caine's "patriarchal" aspects (for example, reviewing his relationship with his sister-in-law Yelina Salas); he comments that they "shape... his relationships to victims and the CSI team, and his relationship to community in general."[10] West extends this analysis into the character's "authoritative yet mildly tolerant" attitude to the entire Miami community, commenting that it is based in Caine's "racial identity... as a white American."[10] He comments that the CSI team stands in for Caine's family, quoting a review of "Blood in the Water" by Kristine Huntley, who highlights the isolating nature of the character's pseudo-parental relationship with his team.[10]

The character has also received critical analysis in comparison with characters from other CSI series such as Gil Grissom and Mac Taylor, as well as other fictional detectives on television.[11][12][13][14] Nichola Dobson characterizes Caine as having a "strong sense of moral justice", compared with Taylor and especially Grissom; she encapsulates Caine as "the avenger and protector".[11] This aspect of his character is illustrated by his catchphrase "We never close", indicating that the search for truth is inexorable, and justice will eventually be delivered.[12] Robert Hampson writes that Caine and Taylor each "establish the ethos of their team" and goes on to describe Caine's ethos as "one of care".[14] Dobson considers the character typical of the television detective, a "maverick 'lone' protector working outside the system".[11] The critic Charles McGrath broadens the comparison to print detectives, describing Caine as a "noirish character" with links to Philip Marlowe.[2]

Michael Arntfield characterizes Caine as a "stoic widower", commenting that three of his close relatives, including his wife, have been murdered by different people; he draws parallels with Taylor, whose wife was a victim of the September 11 attacks; he concludes that the "physical and emotional frailties" of the two characters "consecrate the power of the machine that sustains them", with their work providing "some semblance of stability in their otherwise fractured existences."[13] Lawrence Kramer calls attention to Caine's "wounded" nature, "haunted... by an old trauma", comparing him with the Cold Case character, Lilly Rush.[12] Barbara Kay treats Caine as a "Jesus figure" often depicted "kneeling before orphaned or distressed children, and comforting them"; she notes that his marriage to a "victim-figure with leukemia" was immediately and inevitably followed by his wife's murder.[15] Matthew Gilbert notes the many "literary, pop cultural and even biblical associations" of the character's name, and highlights the allusion to the Cain and Abel story, describing Caine as "living in the shadow of his late brother".[16]

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ In the CSI: Miami sixth season premiere "Dangerous Son", Horatio Caine is revealed to have gone undercover as "John Kelly" in New York City the early 1990s, retroactively indicating Caine to be the same character as Detective John Kelly, David Caruso's NYPD Blue character, who first appeared in the series' pilot, which aired on September 21, 1993.

References

edit- ^ "CSI: Miami - Cast - David Caruso". TV Guide. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Charles McGrath (November 21, 2004). "The Blood-Spattered Triplets of 'CSI'". The New York Times. p. 2.26.

- ^ a b c d Maria Elena Fernandez (January 31, 2005). "'CSI: Miami' spells success with a capital 'H'; The show capitalizes on its tropical 'tude and tough-tender hero, Horatio Caine". Los Angeles Times. p. E1.

- ^ Robert Bianco (September 23, 2002). "Case closed: Caruso's intensity powers 'CSI: Miami'". USA Today. p. D03.

- ^ Robert Bianco (January 13, 2003). "'CSI: Miami' suits older, wiser Caruso". USA Today. p. D03.

- ^ Caryn James (September 23, 2002). "How to Fight Lawlessness? Subdivide Crime Shows". The New York Times. p. E6.

- ^ David Stubbs (14 February 2010). "CSI: a beginner's guide". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 October 2023.

- ^ Amanda Hess (July 25, 2022). "The Framing Of Meryl Streep". The New York Times. p. C1.

- ^ Tom Jicha (April 30, 2007). "Made in the Shades South Florida style and sizzle have transformed CSI: Miami into the hottest show around (even if the CBS drama is mostly filmed in L.A.)". Sun Sentinel. p. E1.

- ^ a b c d e f Patrick West (2009). "The City of Our Times: Space, Identity and the Body in CSI: Miami". In Michele Byers, Val Marie Johnson (ed.). The CSI Effect: Television, Crime, and Governance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739124710.

- ^ a b c Nichola Dobson (2009). "Generic Difference and Innovation in CSI". In Michele Byers, Val Marie Johnson (ed.). The CSI Effect: Television, Crime, and Governance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739124710.

- ^ a b c Lawrence Kramer (2009). "Forensic music". In Michele Byers, Val Marie Johnson (ed.). The CSI Effect: Television, Crime, and Governance. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780739124710.

- ^ a b Michael Arntfield (2011). "TVPD:The Generational Diegetics of the Police Procedural on American Television". Canadian Review of American Studies. 41 (1): 75–95. doi:10.1353/crv.2011.0003.

- ^ a b Robert Hampson (2017). "Sites of Death in Some Recent British Fiction". New Formations: A Journal of Culture/Theory/Politics. 89: 212–29.

- ^ Barbara Kay (May 31, 2006). "The Christological semiotics of CSI". National Post. p. A20.

- ^ Matthew Gilbert (February 22, 2005). "TV characters' names often say something about who they are". The Record. p. F07.

Further reading

edit- Katherine Ramsland. "IQ, EQ, and SQ: Grissom Thinks and Caine Feels, but Taylor Enlightens". In Investigating CSI: An Unauthorized Look Inside the Crime Labs of Las Vegas, Miami and New York (Donn Cortez, ed.) (BenBella Books; 2006)