Koppány, also called Cupan was a Hungarian lord in the late 10th century and leader of pagans opposing the Christianization of Hungary. As the duke of Somogy, he laid claim to the throne based on the traditional idea of seniority, but was defeated and executed by Stephen (born with the pagan name Vajk), son of the previous grand prince Géza.

| Koppány | |

|---|---|

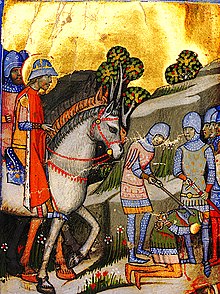

Execution of Koppány as depicted in the Illuminated Chronicle | |

| Duke of Somogy | |

| Reign | After 972 - 997 or 998 |

| Predecessor | Zerind the Bald (?) |

| Successor | None |

| Born | Before 965 |

| Died | 997 or 998 Near Veszprém or in Somogy |

| Dynasty | Árpád dynasty |

| Father | Zerind the Bald |

According to modern scholars' consensus view, he was a member of the royal Árpád dynasty. Koppány was the lord of the southern region of Transdanubia during the reign of Géza, who ruled between the early 970s and 997. After the death of Géza, Koppány laid claim to the throne against Géza's devout Christian son, Stephen. His claim was mainly supported by pagan Hungarians, but the royal army routed his army near Veszprém in 997 or 998. Koppány was killed either in the battle or in his duchy, whither he had fled from the battlefield. His corpse was cut in four pieces to be displayed on the walls of four major strongholds of Hungary, Győr, Veszprém, Esztergom and Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia, Romania).

Family

editHe was the son of Zerind the Bald, according to the 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle.[1] Although no primary source mentions that Koppány was descended from Álmos or Árpád, the first grand princes of the Hungarians, his attempt to seize the throne shows that he was a member of the Árpád dynasty.[2] Historians debate which of the four or five sons of Árpád was Koppány's ancestor.[3] Historians Gyula Kristó, László Szegfű and György Szabados say that Koppány was probably descended from Árpád's oldest son, Tarkatzus,[4][5] but Kornél Bakay (who identified Zerind the Bald with Ladislas the Bald) writes that Árpád's youngest son, Zoltán, was Koppány's forefather.[6] The exact date of Koppány's birth cannot be determined.[7] He was allegedly born between around 950 and 965, because his claim to the throne in 997 shows that he was the oldest member of the Árpád dynasty at that time.[8]

Duke of Somogy

editThe 14th-century Illuminated Chronicle recorded that "Duke Cupan ... held sway over a duchy"[9] (ducatum tenebat, in Latin) during the reign of Géza, Grand Prince of the Hungarians.[10] Géza, who ascended the throne around 972, was described as a cruel monarch in late 11th-century legends.[11] His fame, along with the fact that only a few late-10th-century members of the royal family are known, suggests that Géza murdered most of his kinsmen, according to historian Pál Engel.[12]

Even if Géza carried out a purge among his relatives, Koppány survived it.[12] According to the Illuminated Chronicle, he was "Duke of Symigium" (or Somogy).[12][13] Two later sources—the 15th-century Osvát Laskai and an unknown 16th-century Carthusian monk—mentioned that Koppány had also been the lord of Zala.[14] Based on the sources, modern historians agree that Koppány administered the southwestern region of Transdanubia, most likely between Lake Balaton and the river Dráva.[12][15][16][4] Szabados says that Koppány's father had already dominated Somogy and Zala;[17] in contrast, László Kontler writes that Koppány received his duchy from Géza as a compensation after Géza made his own son, Stephen, his heir.[15]

Rebellion and death

editGéza died in 997.[18] Either in the same or the next year, Koppány revolted against Géza's successor, Stephen, claiming the throne and Géza's widow, Sarolt, for himself.[19][20] His claim to the throne shows that he considered himself the lawful heir to Géza in accordance with the traditional principle of seniority, but in contrast with the Christian law of primogeniture which supported Stephen's right to succeed his father.[18][4] Koppány's effort to marry Géza's widow was also in line with the pagan custom of levirate marriage, but Christians regarded it as an incestuous attempt.[19][21] Both of Koppány's claims suggest that he was pagan, or he inclined to paganism even if he had been baptised.[4]

In the nearly contemporaneous deed of foundation of the Pannonhalma Archabbey, Stephen mentioned that "a certain county named Somogy" attempted to dethrone him after his father's death.[22] The late 11th-century Lesser Legend of King St Stephen declared that "certain noblemen whose hearts were inclined to idle banquets" turned against Stephen after his ascension to the throne.[23][24] Both sources suggest that it was not Stephen who started the war, but that Koppány rebelled against him.[25]

Koppány started to "destroy the castles of Stephen, plunder his properties [and] murder his servants", according to the Lesser Legend.[23] The same source also wrote that Koppány laid siege to Veszprém, but Stephen collected his army, marched to the fortress and annihilated Koppány's troops.[23] The German knights who had settled in Hungary after Stephen married Gisela of Bavaria in 996, played a preeminent role in the victory of the royal army.[26][18] The commander of the royal army, Vecelin, was one of the German immigrants.[27] The deed of foundation of the Pannonhalma monastery even referred to the civil war as a fight between "the Germans and the Hungarians".[22][27]

Koppány was killed by Vecelin in the battle near Veszprém, according to Chapter 64 of the Illuminated Chronicle.[26][28] On the other hand, Chapter 40 of the same source says that Vecelin killed Koppány in Somogy.[29] If the latter report is valid, Koppány fled from the battlefield after his defeat at Veszprém, but the royal army chased and murdered him in his duchy.[30] On Stephen's order, Koppány's body was quartered and its parts were hung over the walls of Esztergom, Veszprém, Győr and Gyulafehérvár (present-day Alba Iulia in Romania).[28]

References

edit- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 240, 243–244.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 243.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 243–251.

- ^ a b c d Kristó 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Szegfű 1994, p. 368.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 247, 251.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 251.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 251–252.

- ^ The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle (ch. 39.64), p. 105.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 252.

- ^ Engel 2001, pp. 26, 387.

- ^ a b c d Engel 2001, p. 26.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 240, 252.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 240, 242.

- ^ a b Kontler 1999, p. 53.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 253, 256.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 253.

- ^ a b c Cartledge 2011, p. 11.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 27.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 261–265.

- ^ Kristó 2001, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b Szabados 2011, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Kristó 2001, p. 19.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 242.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 266.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, pp. 26, 39.

- ^ a b Engel 2001, p. 39.

- ^ a b Kristó 2001, p. 20.

- ^ Szabados 2011, p. 267.

- ^ Szabados 2011, pp. 267–268.

Sources

editPrimary sources

edit- The Hungarian Illuminated Chronicle: Chronica de Gestis Hungarorum (Edited by Dezső Dercsényi) (1970). Corvina, Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-4015-1.

Secondary sources

edit- Cartledge, Bryan (2011). The Will to Survive: A History of Hungary. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-112-6.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. I.B. Tauris Publishers. ISBN 1-86064-061-3.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Kristó, Gyula (2001). "The Life of King Stephen the Saint". In Zsoldos, Attila (ed.). Saint Stephen and His Country: A Newborn Kingdom in Central Europe – Hungary. Lucidus Kiadó. pp. 15–36. ISBN 963-86163-9-3.

- Szabados, György (2011). Magyar államalapítások a IX-X. században [Foundations of the Hungarian States in the 9th–10th Centuries] (in Hungarian). Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 978-963-08-2083-7.

- Szegfű, László (1994). "Koppány". In Kristó, Gyula; Engel, Pál; Makk, Ferenc (eds.). Korai magyar történeti lexikon (9–14. század) [Encyclopedia of the Early Hungarian History (9th–14th centuries)] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 368. ISBN 963-05-6722-9.

Further reading

edit- Györffy, György (1994). King Saint Stephen of Hungary. Atlantic Research and Publications. ISBN 0-88033-300-6.