Kosmos 954 (Russian: Космос 954) was a reconnaissance satellite launched by the Soviet Union in 1977. A malfunction prevented safe separation of its onboard nuclear reactor; when the satellite reentered the Earth's atmosphere the following year, it scattered radioactive debris over northern Canada, some of the debris landing in the Great Slave Lake next to Fort Resolution, NWT.[1][2][3]

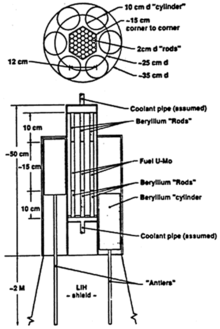

Sketch of Kosmos 954 | |

| Mission type | Reconnaissance |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 1977-090A |

| SATCAT no. | 10361 |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Launch mass | 3,800 kg (8,400 lb) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 13:55:00, 18 September 1977 (UTC) |

| Rocket | Tsyklon-2 |

| Launch site | Tyuratam |

| End of mission | |

| Decay date | 24 January 1978 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Eccentricity | 0.00135 |

| Perigee altitude | 259 km (161 mi) |

| Apogee altitude | 277 km (172 mi) |

| Inclination | 65° |

| Period | 89.6 min |

| Epoch | 18 September 1977 |

This prompted an extensive multiyear cleanup operation known as Operation Morning Light. The Canadian government billed the Soviet Union for over 6 million Canadian dollars under the terms of the Outer Space Treaty, which obligates states for damages caused by their space objects. The USSR eventually paid 3 million Canadian dollars in compensation.[4]

Launch and operation

editThe satellite was part of the Soviet Union's RORSAT programme, a series of reconnaissance satellites which observed ocean traffic, including surface vessels and nuclear submarines, using active radar.[5] It was assigned the Kosmos number 954 and was launched on 18 September 1977 at 13:55 UTC from the Baikonur Cosmodrome, on a Tsyklon-2 carrier rocket.[6][7] With an orbital inclination of 65°, a periapsis of 259 kilometres (161 miles) and apoapsis of 277 kilometres (172 miles), it orbited the Earth every 89.5 minutes.[7] Powered by a liquid sodium–potassium thermionic converter driven by a BES-5 nuclear reactor containing around 50 kg of highly-enriched uranium (over 90% uranium-235),[6][8] the satellite was intended for long-term on-orbit observation, but by December 1977 the satellite had deviated from its designed orbit and its flightpath was becoming increasingly erratic.[9]

In mid-December North American Aerospace Defense Command, which had assigned the satellite the Satellite Catalog Number 10361, noticed Kosmos 954 making erratic manoeuvres, changing the altitude of its orbit by up to 50 miles, as its Soviet operators struggled to control their failing spacecraft.[6] In secret meetings, Soviet officials warned their US counterparts that they had lost control over the vehicle, and that the system which was intended to propel the spent reactor core into a safe disposal orbit had failed.[2]

At 11:53 GMT on 24 January 1978, Kosmos 954 reentered the Earth's atmosphere while travelling on a northeastward track over western Canada.[1][10][4] At first the USSR claimed that the satellite had been completely destroyed during re-entry,[2] but later searches showed debris from the satellite had been deposited on Canadian territory along a 600-kilometre (370 mi) path from Great Slave Lake[11] to Baker Lake. The area spans portions of the Northwest Territories, present-day Nunavut, Alberta, and Saskatchewan.[1][4]

Recovery

editThe effort to recover radioactive material from the satellite was dubbed Operation Morning Light. Covering a total area of 124,000 square kilometres (48,000 sq mi), the joint Canadian–American team swept the area on foot and by air in Phase I from 24 January 1978 to 20 April 1978 and Phase II from 21 April 1978 to 15 October 1978.[1][2] They were ultimately able to recover twelve large pieces of the satellite, ten of which were radioactive.[1] These pieces displayed radioactivity of up to 1.1 sieverts per hour, yet they only comprised an estimated 1% of the fuel. One fragment had a radiation level of 500 R/h, which "is sufficient to kill a person ... remaining in contact with the piece for a few hours."[12]

Aftermath

editUnder the terms of the 1972 Space Liability Convention, a state which launches an object into space is liable for damages caused by that object.[1] For the recovery efforts, the Canadian government billed the Soviet Union Can$6,041,174.70 for expenses and additional compensation for future unpredicted expenses; the USSR eventually paid Can$3 million.[4]

Kosmos 954 was not the first nuclear-powered RORSAT to fail; a launch of a similar satellite in 1973 failed, dropping its reactor into the Pacific Ocean north of Japan. Subsequently, Kosmos 1402 also failed, dropping its reactor into the South Atlantic in 1983. Subsequent RORSATs were equipped with a backup core ejection mechanism, when the primary mechanism failed on Kosmos 1900 in 1988, this system succeeded in raising the core to a safe disposal orbit.[8]

Search teams did not find re-entry debris at the predicted location until they recalculated where that location would be based upon data indicating a stratospheric warming event had been in progress during re-entry. The stratospheric warming was first documented by the US Army Meteorological Rocket Network station at Poker Flat Research Range near Fairbanks, Alaska.[citation needed]

Pop culture

editKosmos 954 has become a well known piece of history and lore in Yellowknife, the capital of the Northwest Territories. Yellowknife painter Nick MacIntosh has created works of art featuring the satellite and well known local landmarks.[13]

The 28 January 1978, episode of Saturday Night Live featured a running gag about the radioactive debris from the crashed satellite having created giant, mutant lobsters heading for the U.S. east coast. The story concluded with them invading the television studio at the show's end.[14]

In November of 2022, an eight-episode podcast series titled Operation Morning Light was released. It was hosted by Dëneze Nakehk'o, a veteran Yellowknife-based Dené broadcast journalist, and produced by Aliya Pabani, and discussed the impact and aftermath of Kosmos 954 on the land and peoples where the debris fell. [15]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f "Settlement of Claim between Canada and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics for Damage Caused by Cosmos 954". April 2, 1981.

- ^ a b c d Reynolds, Glenn H.; Merges, Robert P. (1998). Outer Space: Problems of Law and Policy. Westview Press. pp. 179–189. ISBN 978-0-8133-6680-7.

- ^ Weintz, Steve (23 November 2015). "The Cold War near-atrocity that was nobody's fault". The National Interest. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d Benkö 1985, pp. 49–51.

- ^ "Nation: Cosmos 954: An Ugly Death". Time Magazine. Feb 6, 1978.

- ^ a b c Heaps 1978, p. 13.

- ^ a b "Cosmos 954 (1977-090A)". National Space Science Data Center, NASA.

- ^ a b Harland & Lorenz 2005, p. 236.

- ^ Heaps 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Heaps 1978, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Baker, Howard A. (1989). Space debris: legal and policy implications. Nijhoff. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-7923-0166-0.

- ^ Benkö 1985, pp. 50, 78.

- ^ Rendell, Mark (10 October 2014). "The Fall, And Artistic Rise, Of Kosmos 954". EDGE YK. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- ^ "SNL Transcripts: Robert Klein: 01/21/78: Lobsters Take New York / Goodnights". 8 October 2018.

- ^ "Operation Morning Light". 14 November 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Heaps, Leo (1978). Operation Morning Light : Terror in our Skies : The True Story of Cosmos 954. New York: Paddington Press Ltd. ISBN 0-7092-0323-3.

- Harland, David M; Lorenz, Ralph D. (2005). Space Systems Failures – Disasters and rescues of satellites, rockets, and space probes. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Praxis Publishing (Springer). ISBN 0-387-21519-0.

- Benkö, Marietta (1985). Space law in the United Nations. Martinus Nijhoff. ISBN 978-90-247-3157-2.

External links

edit- Radiation Geophysics – Operation Morning Light – A personal account, Natural Resources Canada – a detailed first-hand account of recovering pieces of Kosmos 954; includes pictures.

- Note verbale dated 19 December 1978 from the Permanent Mission of Canada to the United Nations Description and location of recovered pieces.

- Gus W. Weiss (Spring 1978). "Life and death of Cosmos 954" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. US Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-21. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

- 1978 Cosmos 954 and Operation Morning Light – Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife, North West Territories, Canada