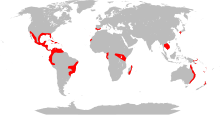

Lantana camara (common lantana) is a species of flowering plant in the verbena family (Verbenaceae), native to the American tropics.[5][6] It is a very adaptable species, which can inhabit a wide variety of ecosystems; once it has been introduced into a habitat it spreads rapidly; between 45ºN and 45ºS and less than 1,400 metres (4,600 feet) in altitude.

| Lantana camara[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flowers and leaves | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Lamiales |

| Family: | Verbenaceae |

| Genus: | Lantana |

| Species: | L. camara

|

| Binomial name | |

| Lantana camara | |

| |

| Global distribution of Lantana camara | |

| Synonyms | |

It has spread from its native range to around 50 countries,[7] where it has become an invasive species.[8][9] It first spread out of the Americas when it was brought to Europe by Dutch explorers and cultivated widely, soon spreading further into Asia and Oceania where it has established itself as a notorious weed, and in Goa Former Estado da Índia Portuguesa it was introduced by the Portuguese.[8]

L. camara can outcompete native species,[10] leading to a reduction in biodiversity.[11] It can also cause problems if it invades agricultural areas as a result of its toxicity to livestock, as well as its ability to form dense thickets which, if left unchecked, can greatly reduce the productivity of farmland[12] by suppressing the pastures (grasses) essential for livestock production and also suppresses crops in cultivated farmlands.[1]

Description

editLantana camara is a perennial, erect sprawling or scandent, shrub which typically grows to around 2 metres (6+1⁄2 feet) tall and form dense thickets in a variety of environments. Under the right conditions, it can scramble up into trees and can grow to 6 m (20 ft) tall.[13][14]

The leaves are broadly ovate, opposite, and simple and have a strong odour when crushed.[15]

L. camara has small tubular-shaped flowers, which each have four petals and are arranged in clusters in terminal areas stems. Flowers come in many different colours, including red, yellow, white, pink and orange, which differ depending on location in inflorescences, age, and maturity.[16] The flower has a tutti frutti smell with a peppery undertone. After pollination occurs, the colour of the flowers changes (typically from yellow to orangish, pinkish, or reddish); this is believed to be a signal to pollinators that the pre-change colour contains a reward as well as being sexually viable, thus increasing pollination efficiency.[17] In frost-free climates the plant can bloom all year round, especially when the soil is moist.[18]

There are five major flower colour varieties in Australia:[19]

- Pink – Bud: pink; Middle ring: yellow opening with pale yellow petals; Outer ring: orange opening with pale or dark pink petals

- White – Bud: cream coloured; Middle ring: yellow opening with light yellow petals; Outer ring: orange or yellow opening with lilac petals

- Pink-edged Red – Bud: pink to reddish pink; Middle ring: orange opening with light yellow to orange petals; Outer ring: orange opening having two pink to red petals

- Red – Bud: blood red; Middle ring: yellow opening with yellow petals; Outer ring: red throat having red petals

- Orange – Bud: orange; Middle ring: yellow to orange opening, yellow petals; Outer ring: orange opening with orange petals

The fruit is a berry-like drupe which turns from green to dark purple when mature. Green unripe fruits are inedible to humans and animals alike. Because of dense patches of hard spikes on their rind, ingestion of them can result in serious damage to the digestive tract. Both seed and vegetative reproduction occur. Up to 12,000 fruits can be produced by each plant.[20]

-

Trunk of an old, large specimen

-

Yellowish flowers are newly opened; magenta flowers are older and have been triggered by pollination to produce more anthocyanins

-

Scarlet flowers on branch in Costa Rica

-

Orange-flowered specimen

-

Tangerine coloured flower

-

Pink and yellow specimen in a shrubland

-

Red-flowered specimen in France

-

Pink-edged red flowers in Adana, Turkey

-

White flowers

-

Pink flowers

-

Yellow flowers

-

Ring of yellow flowers

-

Fruits

-

Ripe fruit

-

Close-up of mature fruits

Taxonomy

editDue to extensive selective breeding throughout the 17th and 18th centuries for use as an ornamental plant, there are now many different cultivars.[4]

Other common names include Cariaquillo (Boriken, Puerto Rico), Visepo (Zambia),Spanish flag, big-sage (Malaysia), Putush (West Bengal), Kongini (Kerala), Ghaneri घाणेरी (Maharashtra), wild-sage, red-sage, white-sage (Caribbean), korsu wiri or korsoe wiwiri (Suriname), mũkigĩ (Kenya), tickberry (South Africa), Kashi Kothan (Maldives),[21] West Indian lantana,[22] umbelanterna, and Gu Phool in Assam, and Thirei in Manipur, and Banfada in Nepal.

Etymology

editThe name Lantana derives from the Latin name of the wayfaring tree Viburnum lantana, the flowers of which closely resemble Lantana.[8][23]

Camara is derived from Greek, meaning 'arched', 'chambered', or 'vaulted'.[23]

Distribution and habitat

editThe native range of Lantana camara is Central and South America; however, it has become naturalised in around 60 tropical and sub-tropical countries worldwide.[24][25] It is found frequently in east and southern Africa, where it occurs at altitudes below 2,000 m (6,600 ft), and often invades previously disturbed areas such as logged forests and areas cleared for agriculture.[26] L. camara has also spread across the areas of Africa, Southern Europe, such as Spain and Portugal, and also the Middle East, India, tropical Asia, Australia, New Zealand, and the US, as well as many Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean islands.[27][28] It has become a significant weed in Sri Lanka after escaping from the Royal Botanical Gardens in 1926.[29][30] Lantanas were brought to Australia as an ornamental garden plant in 1841, which spread and escaped domestic cultivation and became established in the wild within 20 years.[31] They were brought to India by the British around 200 years ago, which then spread and became invasive there as well.[32] A national-level monitoring in 2023 found that L. camara has invaded around 50% of the natural areas in India.[33]

It was introduced into the Philippines from Hawaii as part of an exchange program between the United States and the Philippines; however, it managed to escape and has become naturalized in the islands.[29] It has also been introduced to the whole southern US, from California to North Carolina,[34] and is considered hardy in US Department of Agriculture zones 10 and 11.[35]

The range of L. camara is still increasing, shown by the fact that it has invaded many islands on which it was not present in 1974, including the Galapagos Islands, Saipan and the Solomon Islands.[28] There is also evidence that L. camara is still increasing its range in areas where it has been established for many years, such as East Africa, Australia and New Zealand.[7] The ability of L. camara to rapidly colonise areas of land which have been disturbed has allowed it to proliferate in countries where activities such as logging, clearance for agriculture and forest fires are common. In contrast, in countries with large areas of intact primary forest, the distribution of L. camara has been limited.[7][36]

Ecology

edit-

Antillean crested hummingbird feeding from specimen

-

Red-backed mannikin picking flowers

-

Long-tailed skipper resting on specimen

-

Twin Lantana camara 'Patty Wankler' with crab spider waiting for prey

Birds and other animals eat the seeds, helping spread them over large distances.

Habitat

editThe species is found in a variety of environments, including:

- Agricultural areas

- Forest margins and gaps

- Riparian zones

- Grasslands

- Secondary forest, and

- Beach fronts.

L. camara is rarely found in natural or semi-natural areas of forest, as it is unable to compete with taller trees due to its lack of tolerance for shade.[21] Instead it grows at the forest edge. L. camara can survive in a wide range of climatic conditions, including drought, different soil types, heat, humidity and salt. It is also relatively fire tolerant and can quickly establish itself in recently burnt areas of forest.[26][37]

As an invasive species

editL. camara is listed in the IUCN's "List of the world's 100 worst invasive species".[38] L. camara is considered to be a weed in large areas of the Paleotropics where it has established itself. In agricultural areas or secondary forests it can become the dominant understorey shrub, crowding out other native species and reducing biodiversity.[21] The formation of dense thickets of L. camara can significantly slow down the regeneration of forests by preventing the growth of new trees.[4]

In the US, L. camara is considered invasive in tropical areas such as Florida and Hawaii.[34]

In Thailand, some species of Phakakrong are weeds that can be found throughout the country. Most outbreaks were found in Mae Hong Son and Kanchanaburi provinces.

Although L. camara is itself quite resistant to fire, it can change fire patterns in a forest ecosystem by altering the fuel load, causing a buildup of forest fuel, which itself increases the risk of fires spreading to the canopy.[39] This can be particularly destructive in dry, arid areas where fire can spread quickly and lead to the loss of large areas of natural ecosystem.

L. camara reduces the productivity in pasture through the formation of dense thickets, which reduce growth of crops as well as make harvesting more difficult. There are also secondary impacts, including the finding that in Africa, mosquitos which transmit malaria and tsetse flies shelter within the bushes of L. camara.[40]

While a study in the Western Ghats, did not find significant impacts of L. camara invasion on a few native plant indicators, many other studies have found substantial impacts of its invasion on various biodiversity indicators.[41][42]

There are many reasons why L. camara has been so successful as an invasive species; however, the primary factors which have allowed it to establish itself are:

- Wide dispersal range made possible by birds and other animals that eat its drupes

- Less prone to being eaten by animals due to toxicity

- Tolerance of a wide range of environmental conditions[21]

- Increase in logging and habitat modification, which has been beneficial to L. camara as it prefers disturbed habitats[43]

- Historical hybridization between various species and varities that helped L. camara adapt to novel environments.[43]

- Production of toxic chemicals which inhibit competing plant species

- Extremely high seed production (12,000 seeds from each plant per year)[44]

Management and control

editEffective management of invasive L. camara in the long term will require a reduction in activities that create degraded habitats. Maintaining functioning (healthy) ecosystems is key to preventing invasive species from establishing themselves and out-competing native fauna and flora. If the area is not very large, use the method of clearing and digging out the roots. Chemicals may be used for disposal. In some areas, natural Phakarang trees are dug up and bred to become beautiful ornamental plants.

Biological

editInsects and other biocontrol agents have been implemented with varying degrees of success in an attempt to control L. camara. It was the first weed ever subjected to biological control; however, none of the programs have been successful despite 36 control agents being used across 33 regions.[45]

The lack of success using biological control in this case is most likely due to the many hybrid forms of L. camara, as well as its large genetic diversity which makes it difficult for the control agents to target all plants effectively. A recent study in India has shown some results around biological control of this plant using tingid bugs.[46]

Mechanical

editMechanical control of L. camara involves physically removing the plants. Physical removal can be effective but is labour-intensive and expensive,[21] therefore removal is usually only appropriate in small areas or at the early stages of an infestation. Another method of mechanical control is to use fire treatment, followed by revegetation with native species.

Chemical

editUsing herbicides to manage L. camara is very effective but also expensive, prohibiting its use in many poorer countries where L. camara is well established. The most effective way of chemically treating plant species is to first mow the area, then spray the area with a weed-killer, although this may have serious environmental consequences.[citation needed]

Toxicity

editLantana camara is known to be toxic to livestock such as cattle, sheep, horses, dogs and goats.[47][48] The active substances causing toxicity in grazing animals are pentacyclic triterpenoids called Lantadenes, which result in liver damage and photosensitivity.[49] L. camara also excretes allelopathic chemicals, which reduce the growth of surrounding plants by inhibiting germination and root elongation.[50]

The toxicity of L. camara to humans is undetermined, with several studies suggesting that ingesting berries can be toxic to humans, such as a study by O. P. Sharma which states "Green unripe fruits of the plant are toxic to humans".[51] North Carolina State University's Extension Gardener website states that ingestion of the flowers, fruits, and leaves can cause vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty breathing, and liver failure, while the leaves can cause contact dermatitis.[52] A field guide by the US Department of the Army says the plant can even be fatal.[53] Contrarily, some studies have claimed that the species poses no risk to humans when eaten, and is in fact edible when ripe.[54][55]

Uses

editLantana camara stalks have been used in the construction of furniture, such as chairs and tables;[56] however, the main uses have historically been medicinal and ornamental.

Medicinal value

editStudies conducted in India have found that Lantana leaves can display antimicrobial, fungicidal and insecticidal properties.[4][57] L. camara has also been used in traditional herbal medicines for treating a variety of ailments, including cancer, skin itches, leprosy, chicken pox, measles, asthma and ulcers.[4]

L. camara extract has shown to reduce gastric ulcer development in rats.[58]

Ornamental

editLantana camara has been grown specifically for use as an ornamental plant since Dutch explorers first brought it to Europe from the New World.[4] Its ability to last for a relatively long time without water, and the fact that it does not have many pests or diseases which affect it, have contributed to it becoming a common ornamental plant. L. camara also attracts butterflies and birds and is frequently used in butterfly gardens.[5] As an ornamental, L. camara is often cultivated indoors, or in a conservatory, in cool climates, but can also thrive in a garden with sufficient shelter.[59]

As a host plant

editMany butterfly species feed on the nectar of L. camara. Papilio homerus, the largest butterfly in the western hemisphere, is known to feed on the nectar of the flowers as an opportunistic flower feeder.[60] A jumping spider, Evarcha culicivora, has an association with L. camara. They consume the nectar for food and preferentially use these plants as a location for courtship.[61]

References

edit- ^ Munir A (1996). "A taxonomic review of Lantana camara L. and L. montevidensis (Spreng.) Briq. (Verbenaceae) in Australia". Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens. 17: 1–27.

- ^ "NatureServe Explorer".

- ^ "Lantana aculeta L." U.S National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS). Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Global Invasive Species Database". issg.org.uk. Archived from the original on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-03-22.

- ^ a b Floridata LC (2007). "Lantana camara". Floridata LC. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ Moyhill Publishing (2007). "English vs. Latin Names". Moyhill Publishing. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Day, M. D. (December 24, 2003). Lantana: current management status and future prospects. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research. ISBN 978-1-86320-375-3. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c Ghisalberti, E.L. (2000). "Lantana camara L. (Verbenaceae)". Fitoterapia. 71 (5): 467–486. doi:10.1016/S0367-326X(00)00202-1. PMID 11449493.

- ^ Sharma, OM.P.; Harinder, Paul S (1988). "A review of the noxious plant Lantana camara". Toxicon. 26 (11): 975–987. doi:10.1016/0041-0101(88)90196-1. PMID 3072688.

- ^ Kasaga, Lawrence (March 2022). Impact of Lantana camara on native vegetation structure and diversity of Kakiika, Mbarara, Uganda (BSc thesis). Makerere University. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.31037.95206. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

- ^ Kohli, Ravinder. K. (2006). "Status, invasiveness and environmental threats of three tropical American invasive weeds (Parthenium hysterophorus L., Ageratum conyzoides L., Lantana camara L.) in India". Biological Invasions. 8 (7): 1501–1510. Bibcode:2006BiInv...8.1501K. doi:10.1007/s10530-005-5842-1. S2CID 23302783.

- ^ Ensbey, Rob. "Lantana - Weed of National Significance".

- ^ Lantana camara L. WEEDS AUSTRALIA - PROFILES. Centre for Invasive Species Solutions.

- ^ Sharma, O.P. (1981). "A Review of the Toxicity of Lantana camara (Linn) in Animals". Clinical Toxicology. 18 (9): 1077–1094. doi:10.3109/15563658108990337. PMID 7032835.

- ^ Rosacia, W. Z.; et al. (2004). "Lantana and Hagonoy: Poisonous weeds prominent in rangeland and grassland areas" (PDF). Research Information Series on Ecosystems. 16 (2). Retrieved July 27, 2011.

- ^ MOHAN RAM, H.Y. (1984). "Flower Colour Changes in Lantana camara". Journal of Experimental Botany. 35 (11): 1656–1662. doi:10.1093/jxb/35.11.1656.

- ^ Weiss, Martha. R. (1990). Floral Color Changes As Cues For Pollinators. ISHS Acta Horticulturae 288: VI International Symposium on Pollination.

- ^ Lantana Rod Ensbey, Regional Weed Control Coordinator, Grafton. September 2008.

- ^ Identification Guide: Lantana flowers Lantana – A Weed of National Significance (www.nrm.qld.gov.au). Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ^ "Lantana camara". 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-07-30. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ^ a b c d e Quentin C. B. Cronk, Janice L. Fuller (1995). Plant Invaders: The Threat to Natural Ecosystems. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew: Springer. ISBN 978-0-412-48380-6.

- ^ "Lantana camara". Plants Rescue. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ a b Gledhill, David (2008). "The Names of Plants". Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521866453 (hardback), ISBN 9780521685535 (paperback). pp 87,230

- ^ Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (2005). "Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council: Lantana camanara" (PDF). Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-17. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ Sanders, R.W. (2012). "Taxonomy of Lantana sect Lantana (Verbenaceae)". Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas. 6 (2): 403–442.

- ^ a b Gentle, C. B. (1974). "Lantana camara L. invasions in dry rainforest–open forest ecotones: The role of disturbances associated with fire and cattle grazing". Australian Journal of Ecology. 22 (3): 298–306. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1997.tb00675.x.

- ^ "Lantana camara". October 2006. Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ^ a b Thaman, R. R. (2006). "Lantana camara: its introduction, dispersal and impact on islands of the tropical Pacific Ocean". Micronesia Journal of the University of Guam. 10: 17–39.

- ^ a b Forest Invasive Species: Country Report (PDF) (Report). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.[dead link]

- ^ S. Ranwala, B. Marambe, S. Wijesundara, P. Silva, D. Weerakoon, N. Atapattu, J. Gunawardena, L. Manawadu, G. Gamage, Post-entry risk assessment of invasive alien flora in Sri Lanka-present status, GAP analysis, and the most troublesome alien invaders, Pakistan Journal of Weed Science Research, Special Issue, October, 2012: 863-871.

- ^ Lantana NSW Department of Planning and Environment

- ^ In Bandipur, the war against Lantana by The Hindu

- ^ Mungi, Ninad Avinash; Qureshi, Qamar; Jhala, Yadvendradev V. (November 2023). "Distribution, drivers and restoration priorities of plant invasions in India". Journal of Applied Ecology. 60 (11): 2400–2412. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.14506. ISSN 0021-8901.

- ^ a b "Plants Profile for Lantana camara (lantana)". plants.usda.gov. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ "Lantana camara". Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ Duggin, J.A; Gentle, C.B (1998). "Experimental evidence on the importance of disturbance intensity for invasion of Lantana camara L. in dry rainforest–open forest ecotones in north-eastern NSW, Australia". Forest Ecology and Management. 109 (1–3): 279–292. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(98)00252-7.

- ^ Fensham, R. J; Fairfax, R. J; Cannell, R. J (1994). "The invasion of Lantana camara L. in Forty Mile Scrub National Park, north Queensland". Austral Ecology. 19 (3): 297–305. Bibcode:1994AusEc..19..297F. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.1994.tb00493.x.

- ^ Lowe S.; Browne M.; Boudjelas S.; De Poorter M. (2000). "100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species. A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database" (PDF). The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Berry, Z C; Wevill, K; Curran, T J (2011). "The invasive weed Lantana camara increases fire risk in dry rainforest by altering fuel beds". Weed Research. 51 (5): 525–533. Bibcode:2011WeedR..51..525B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3180.2011.00869.x.

- ^ Okoth J. O. (1987). "A study of the resting sites of Glossina fuscipes fuscipes (Newstead) in relation to Lantana camara thickets and coffee and banana plantations in the sleeping sickness epidemic focus, Busoga, Uganda". Uganda Trypanosomiasis Research Organization. 8: 57–60. doi:10.1017/S1742758400006962 (inactive 1 November 2024). S2CID 87065966.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Effect of weeds Lantana camara and Chromelina odorata growth on the species diversity, regeneration and stem density of tree and shrub layer in BRT sanctuary" (PDF).

- ^ Rastogi, Rajat; Qureshi, Qamar; Shrivastava, Aseem; Jhala, Yadvendradev V. (2023-03-01). "Multiple invasions exert combined magnified effects on native plants, soil nutrients and alters the plant-herbivore interaction in dry tropical forest". Forest Ecology and Management. 531: 120781. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120781. ISSN 0378-1127.

- ^ a b Mungi, Ninad Avinash; Qureshi, Qamar; Jhala, Yadvendradev V. (2020-09-01). "Expanding niche and degrading forests: Key to the successful global invasion of Lantana camara (sensu lato)". Global Ecology and Conservation. 23: e01080. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2020.e01080. ISSN 2351-9894.

- ^ "Weed Management Guide – Lantana" (PDF). Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Management Information". Global Invasive Species Database. Retrieved March 24, 2014.

- ^ "Karnataka gets nature's gift to fight deadly weed - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2017-08-21.

- ^ Ross, Ivan. A. (1999). Medicinal plants of the world (PDF). Humana Press. p. 187. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-14. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- ^ Burns, D. (2001). Storey's Horse-Lover's Encyclopedia: an English & Western A-to-Z Guide. Storey Publishing. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-58017-317-9.

- ^ Barceloux, D. G. (2008). Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. Wiley. pp. 867–8. ISBN 978-0-471-72761-3.

- ^ Ahmed. R (2007). "Allelopathic effects of Lantana camara on germination and growth behavior of some agricultural crops in Bangladesh". Journal of Forestry Research. 18 (4): 201–304. doi:10.1007/s11676-007-0060-6. S2CID 61760.

- ^ Sharma O. P. (2007). "A review of the hepatotoxic plant Lantana camara". Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 37 (4): 313–352. doi:10.1080/10408440601177863. PMID 17453937. S2CID 23993698.

- ^ "Lantana camara (Common Lantana, Lantana, Red Sage, Shrub Verbena, Yellow Sage) | North Carolina Extension Gardener Plant Toolbox". plants.ces.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 2021-03-09.

- ^ The Complete Guide to Edible Wild Plants. New York: Skyhorse Publishing & United States Department of the Army. 2009. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-60239-692-0. OCLC 277203364.

- ^ Herzog et al. (1996), Coppens d'Eeckenbrugge & Libreros Ferla (2000), TAMREC (2000)

- ^ Carstairs, S. D.; et al. (December 2010). "Ingestion of Lantana camara is not associated with significant effects in children". Pediatrics. 126 (6): e1585–8. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1669. PMID 21041281. S2CID 36904122.

- ^ Khanna, L. S.; Prakash, R. (1983). Theory and Practice of silvicultural Systems. International Book Distributions.

- ^ Chavan, S.R.; Nikam, S.T. (1982). "Investigation of Lantana camara Linn (Verbenaceae) leaves for larvicidal activity". Bulletin of Haffkine Institute. 10 (1): 21–22.

- ^ Sathish, R.; et al. (March 2011). "Antiulcerogenic activity of Lantana camara leaves on gastric and duodenal ulcers in experimental rats". J Ethnopharmacol. 134 (1): 195–7. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2010.11.049. PMID 21129476.

- ^ "Lantana". BBC Plant Finder.

- ^ Lehnert, Matthew S.; Kramer, Valerie R.; Rawlins, John E.; Verdecia, Vanessa; Daniels, Jaret C. (2017-07-10). "Jamaica's Critically Endangered Butterfly: A Review of the Biology and Conservation Status of the Homerus Swallowtail (Papilio (Pterourus) homerus Fabricius)". Insects. 8 (3): 68. doi:10.3390/insects8030068. PMC 5620688. PMID 28698508.

- ^ Cross, Fiona R.; Jackson, Robert R. (2009). "Odour-mediated response to plants by Evarcha culicivora, a blood-feeding jumping spider from East Africa". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 36 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1080/03014220909510142.

External links

edit- "Lantana Lantana camara". Weeds of National Significance. Weeds Australia. Archived from the original on 2014-01-27.

- "Lantana Control Tips" (PDF). Weeds of National Significance. Weeds Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- USDA Forest service brochure

- Invasion of Exotic Weeds in the Natural Forests of Tropical India due to Forest Fire – A Threat to Biodiversity. International Forest Fire News. 2002.

- Dressler, S.; Schmidt, M. & Zizka, G. (2014). "Lantana camara". African plants – a Photo Guide. Frankfurt/Main: Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg.