Major-General Sir Lee Oliver Fitzmaurice Stack, GBE, CMG (15 May 1868 – 20 November 1924) was a British Army officer and Governor-General of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[1] On 19 November 1924, he was shot by assassins while driving through Cairo, and died of his wounds the next day.[2]

Major-General Sir Lee Stack | |

|---|---|

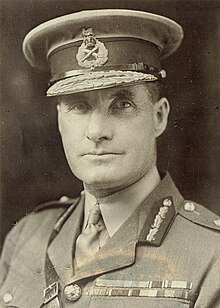

Stack, c. 1924 | |

| Governor-General of Sudan | |

| In office 1917 – 19 November 1924 | |

| Preceded by | Reginald Wingate |

| Succeeded by | Geoffrey Francis Archer |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 May 1868 Darjeeling, India |

| Died | 20 November 1924 (aged 56) Cairo, Egypt |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | British Army |

| Years of service | 1888–1924 |

| Rank | Major-General |

Early life

editBorn in Darjeeling, India, Lee Stack was the son of the British Inspector-General of Police for Bengal. He was educated at Clifton College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.[1][3]

Career

editAfter service with the British Army, Major Lee Stack was seconded to the Egyptian Army in 1899. In addition to regimental appointments he served as Military Secretary to General Sir Reginald Wingate. He received the Order of Osmanieh, third class, from the Khedive of Egypt in 1902.[4] Stack left the army in 1910 but took up the position of Civil Secretary of the Sudan in 1913, based in Khartoum. On the outbreak of war in 1914 he was granted the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel,[5] and in 1917 that of major-general[6] when he became Sirdar of the Egyptian Army, combining this appointment with that of Governor General of the Sudan.[7]

Assassination

editOn 19 November 1924 Sir Lee Stack, accompanied by an aide de camp, was being driven from the Egyptian War Office in Cairo to his official residence. His car had halted in heavy traffic to give a tram car right of way when several Egyptian students grouped on the pavement fired a volley of revolver shots into the vehicle. Stack's driver, Frederick Hamilton March, although injured, was able to accelerate the car away from the scene of the shooting and reach the nearby residence of the British High Commissioner to Egypt. Stack suffered wounds to the hand, stomach, and foot. He died the next day.[8]

Aftermath

editThe British High Commissioner Lord Allenby responded with anger, presenting a list of demands to the Egyptian government which included a public apology, an inquiry, suppression of demonstrations and payment of a fine. Furthermore, he demanded withdrawal of all Egyptian officers and Egyptian army units from the Sudan, an increase to the scope of an irrigation scheme in Gezira and laws to protect foreign investors in Egypt.[9]

Seven men convicted of involvement in the assassination were executed by hanging in 1925. Several were identified by a taxi driver whose vehicle they had commandeered to escape from the scene. The pistols used were identified through a pioneering instance of bullet examination by forensic scientist Sydney Smith.[10]

Sir Geoffrey Archer, formerly Governor of Uganda, took over as Governor-General of the Sudan in January 1925, the first time a civilian had held this office.[11]

References

edit- ^ a b Daly, M.W. (September 2004). "'Stack, Sir Lee Oliver Fitzmaurice (1868–1924)'". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36230. Retrieved 10 February 2009. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Chamberlain, Austen; Robert C. Self (1995). The Austen Chamberlain Diary Letters: The Correspondence of Sir Austen Chamberlain with His Sisters Hilda and Ida, 1916-1937. Cambridge University Press. p. 300. ISBN 0-521-55157-9.

- ^ "No. 25785". The London Gazette. 10 February 1888. p. 895.

- ^ "No. 27476". The London Gazette. 23 September 1902. p. 6075.

- ^ "No. 28977". The London Gazette. 17 November 1914. p. 9408.

- ^ "No. 29887". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1917. p. 59.

- ^ "Sudan". World Statesmen. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "The Assassination of Sir Lee Stack". Townsville Daily Bulletin (QLD. : 1907 - 1954). The Townsville Daily Bulletin. 24 November 2014. p. 4. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "EGYPT: Shots and Repercussions". Time Magazine. 1 December 1924. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 30 August 2011.

- ^ "Going Ballistic: The Forgotten Origins of Forensic Weapon Identification, 1919-1924" (PDF). Berkeley Law University of California. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Ibrahim, Hassan Ahmed (2004). Sayyid ʻAbd al-Raḥmān al-Mahdī: a study of neo-Mahdīsm in the Sudan, 1899-1956. Brill. p. 92. ISBN 90-04-13854-4.