The Lindenmeier site is a stratified multi-component archaeological site most famous for its Folsom component. The former Lindenmeier Ranch is in the Soapstone Prairie Natural Area, in northeastern Larimer County, Colorado, United States. The site contains the most extensive Folsom culture campsite yet found with calibrated radiocarbon dates of c. 12,300 B.P. (10,300 BCE).[3] Artifacts were also found from subsequent Archaic and Late pre-historic periods.

Lindenmeier site | |

The arroyo surrounding the Lindenmeier site. | |

| Nearest city | Fort Collins, Colorado |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 66000249 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | January 20, 1961[2] |

The site was declared a National Historic Landmark on January 20, 1961.[2] The United States National Park Service has studied the possibility of making the Lindenmeier site a United States National Monument.

History

editPaleo-Indian period

editThe period immediately preceding the first humans coming into Colorado was the Ice Age Summer starting about 16,000 years ago. For the next five thousand years the landscape would change dramatically and most of the large animals would become extinct. Receding and melting glaciers created the Plum and Monument Creeks, the Castle Rock mesas and unburied the Rocky Mountains. Large mammals, such as the mastodon, mammoth, camels, giant sloths, cheetah, bison antiquus, and horses roamed the land.[4]

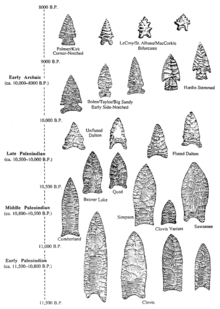

There were a few Paleo-Indian cultures, distinctive by the size of the tools they used and the animals they hunted. People in the first, Clovis complex period, had large tools to hunt the megafauna animals of the early Paleo-Indian period.[4]

With time, the climate warmed again and lakes and savannas receded. The land became drier, food became less abundant, and as a result the giant mammals became extinct. People adapted by hunting smaller mammals and gathering wild plants to supplement their diet.[5] A new cultural complex was born, the Folsom tradition,[6] with smaller projectile points to hunt smaller animals.[4] Aside from hunting smaller mammals, people adapted by gathering wild plants to supplement their diet.[5]

The Lindenmeier site, the largest known Paleo-Indian Folsom site,[7] contained artifacts of the Paleo-Indians who lived and hunted in the present Fort Collins area approximately 11,000 years ago. Some of the artifacts are identified from people of the Folsom tradition, named for the Folsom site in New Mexico, and identified as such by the Folsom points used for hunting the large, now extinct Bison antiquus. They likely also gathered food in the area, such as seeds, nuts and seasonal fruits. They were nomadic people, following the bison herds, and camping many places each year.[8][9]

The tools and artifacts at the Lindenmeier site shed insight into the life of these Paleo-indians:[10][11]

- They created many types and shapes of tools, including spearheads and wedge shaped scrapers, which were essentially identical to the tools of the north Paleo-Indians of central Alaska. The tools were used for chopping, slicing and skinning the hides of the bison. Broken pieces of completed tools indicate that they had been used with great pressure.

- Scored pieces of hematite were used to extract red ochre for rouge or red paint for their faces.

- Round discs of 1–2 inches in diameter were found with indented rims, designs and highly polished – the oldest form of Paleo-Indian artwork found in Colorado.

- The volume and variety of artifacts indicate that the site was a residential campsite, the oldest site of its kind found of the people of the Folsom tradition.

While bison were the mainstay of the hunter's diet, an ancient camel bone was found near a bison kill site. Being limited to one bone, it was likely carried from another area and did not necessarily indicate that the Folsom people hunted camel at Lindenmeier or at other sites.[12]

Post-Folsom periods

editThe site has yielded evidence of occupation of the Lindenmeier site area over 13,000 years. While most of the artifacts were from the Folsom tradition, there are also artifacts gathered from post Folsom periods. Yuma points were also found on the site, were likely from a period a little later than the Folsom artifacts. Unfluted points were found on the Lindenmeier site from the Archaic and Late pre-historic periods and evidence of a late prehistoric kill site. The limited number of artifacts from this and other post-Folsom periods seem to indicate that the later people were more transitory than the people of the Folsom tradition or that there were limited resources in later years.[13]

Artifacts by cultural period

editExcavations resulted in the collection of tens of thousands of stone and bone artifacts. Artifacts were found from the Paleo-Indian, Archaic, and late Prehistoric periods.[14]

| Post-Pleistocene period | Time period | Culture traditions | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paleo-Indian[5] | 11,500 to 8,000 B.P. | Folsom Late Paleo-Indians |

Primarily hunters of large mammals |

| Archaic[15] | 8,000 to 2,200 B.P. | Yuma tradition[nb 1] McKean tradition[nb 2] |

Hunters of smaller game, such as deer, antelope and rabbits, and gatherers of wild plants. The people moved seasonally to hunting and gathering sites. Late in the Archaic period, about 200–500 A.D., corn was introduced into the diet and pottery-making became an occupation for storing and carrying food. |

| Late pre-historic[17] | 2,200 B.P. until arrival of Europeans | The groups of people during this period became much more diverse, were more likely to settle in a location or a couple of locations, cultivate, domesticate animals, make pottery and baskets, and perform ceremonial rituals. |

Archaeological research

editCoffin family

editInvestigations of the Lindenmeier site and stone tools recovered from its location began in 1924 by the Coffin family.

The site was discovered in the summer of 1924 by A. Lynn Coffin, his father Judge Claude C. Coffin, and possibly Forest Service Ranger C. K. Collins.[18][19] After the initial discovery, Major Roy G. Coffin also visited the site repeatedly with his brother the Judge and A. Lynn. They could not correlate the spear points that they found until Dr. E. B. Renaud from the Anthropology department at University of Denver identified them as Folsom points found in 1926 at the Folsom site in New Mexico. Excavation over 10 years generated an unprecedented collection of Folsom point artifacts and bison bones and stimulated interest at the United States Geological Society, Bureau of American Ethnology and many in the American Anthropology field. In 1937 Roy Coffin publishes Northern Colorado's First Settlers about the Coffin's work from 1924 to 1934. The site is named after William Lindenmeier, Jr., who was the landowner at the time of discovery and intensive investigations.[20]

Professional study

edit- The bulk of professional work conducted at the site was completed between 1934 and 1940, headed by Frank H. H. Roberts of the Smithsonian Institution, with annual reports made from 1935 to 1951.[21] Large bison bones were found that indicated that the ancient bison was approximately 7 feet tall.[22]

- In 1937 Dr. Kirk Bryan and Louis L. Ray dated the site of the artifacts from the Late Glacial period.[21]

- John L. Cotter directed work for a team from the Colorado Museum of Natural History, presently named Denver Museum of Nature and Science, from 1935 to 1938, when all major excavation work on the site was completed.[23][nb 3]

- C. Vance Haynes, Jr. and George Agogino in 1960 obtained the first radiocarbon date for the occupation of Lindenmeier Valley.[21] In 1992 C. Vance Haynes, Jr. and other published the radiocarbon date of 10,600 to 10,720 B.P.[24]

Artifact collections

editAs of 2002, artifacts from the Lindenmeier site were held by:[25]

- Claude C. and A. Lynn Coffin Lindenmeier collection with 1,125 artifacts, many of which are held at the Smithsonian Institution

- Major Roy G. Coffin collection at the Fort Collins Museum & Discovery Science Center

- Denver Museum of Nature and Science

Eiseley's Flight 857

editAs a young man, the writer Loren Eiseley participated in the early excavations at Lindenmeier. In his poem "Flight 857" from his book Notes of an Alchemist, he recorded his reflections on the significance of the Lindenmeier site finds:

Nosing in through a blizzard over Denver

at thirty thousand feet

I think what the earth covers at Lindenmeier there far away to the

north

those men we never found

of ten millennia ago ...[26]

Soapstone Prairie Natural Area

editThe City of Fort Collins purchased the site in 2004 as part of Soapstone Prairie Natural Area, which was opened to the public in 2009. The site is viewable from an overlook with interpretive signage.[27]

See also

edit- Folsom site, National Historic Landmark, in New Mexico

- Roxborough State Park Archaeological District – Paleo-Indians, Archaic, and Woodland periods

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Larimer County, Colorado

- List of prehistoric sites in Colorado

Notes

edit- ^ Yuma points, also called Eden points, were first found in Yuma, Colorado and then in Eden, Wyoming. They are lanceolate (leaf-shaped) blades and points used from 9,500 to 7,000 B.C.

- ^ From the middle Archaic period, approximately 7,000 to 5,000 B.P. generally in northeast Wyoming. Marked by the stemmed lanceolate McKean projectile.[16]

- ^ Gantt names the museum that Cotter worked for as the "Colorado Museum of Natural History", a name also attributed to the University of Colorado Museum of Natural History". On page 55 of his document he clearly correlates, though, Colorado Museum of Natural History to the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.

References

edit- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Lindenmeier Site". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 4, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ "Lindenmeier Folsom Site". Colorado Encyclopedia. History Colorado. Retrieved April 15, 2023.

- ^ a b c Waldman, 5.

- ^ a b c Griffin-Pierce, 130.

- ^ Johnson, Raynolds.

- ^ Gantt, 1.

- ^ Rocky Mountain National Park: Tales, Trails and Tribes.

- ^ Local History Archive: A Tour of the Lindenmeier/Folsom Site.

- ^ Coffin, pp. 14–18.

- ^ Gantt, 41.

- ^ Gantt, 42.

- ^ Gantt, 2, 41, 130, 151, 163.

- ^ Robert, Frank H.H.

- ^ Griffin-Pierce, 94–95.

- ^ Kipfer, 341.

- ^ Waldman, 14.

- ^ Coffin, p. 5.

- ^ Wilmsen, Roberts.

- ^ Coffin, pp. 6–12.

- ^ a b c Gantt, 19.

- ^ Coffin, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Gantt, 19, 55.

- ^ Haynes, et al., 83–100.

- ^ Gantt, iii–iv, 1–2.

- ^ Eiseley, Loren.

- ^ Soapstone Prairie Natural Area.

Bibliography

edit- Coffin, Roy G. (1937). "Northern Colorado's First Settlers" (PDF). Colorado State University. pp. 14–18. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Eiseley, Loren. "Flight 857" (PDF). Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Gantt, Erik M. The Claude C. and A. Lynn Coffin Lindenmeier Collection. Colorado State University. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (2010). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southwest. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12790-5.

- Haynes Jr., C. Vance; Beukens, Roelf P.; Jull, A.J.T.; Davis, Owen K. (1992). Stanford, D. J.; Day, J. S. Day (eds.). New Radiocarbon Dates for Some Old Folsom Sites: Accelerator Technology. In Ice Age Hunters of the Rockies. Niwot, Colorado: Denver Museum of Natural History and University of Colorado Press. pp. 83–100.

- Johnson, Kirk R.; Raynolds, Robert G. (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- Kipfer, Barbara Ann (2000). Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. New York: Plenum Publisher. ISBN 0-306-46158-7.

- "Local History Archive: A Tour of the Lindenmeier/Folsom Site (partial transcription of September 1, 1980 recorded talk)". Fort Collins Public Library. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- Robert, Frank H.H. (1935). "A Folsom Complex: Preliminary Report on Investigations at the Lindenmeier Site in Northern Colorado". Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 94 (4).

- "Soapstone Prairie Natural Area". City of Fort Collins. 1996–2011. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- "Rocky Mountain National Park: Tales, Trails and Tribes". University Press of Colorado. 1997. Retrieved September 19, 2011.

- Waldman, Carl (2009) [1985]. Atlas of the North American. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-6858-6.

- Wilmsen, E.N.; Roberts, F.H.H. (1978). "Lindenmeier, 1934–1974: Concluding Report on Investigations". Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology. 24. Washington, D.C.

Further reading

edit- Ambler, Bridget M. (1999). Folsom Chipped Stone Artifacts from the Lindenmeier Site, Colorado: The Coffin Collection Department of Anthropology, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado.

- Cotter, John L. (1978). A Report of Fieldwork of the Colorado Museum of Natural History at the Lindenmeier Folsom Campsite. In Lindenmeier, 1934–1974: Concluding Report on Investigations. Washington, D.C. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Hughes, J. Donald. (c. 1977). American Indians of Colorado Boulder.

- Frison, George C. (1978). Prehistoric Hunters of the Great Plains. New York.

- Jennings, Jesse D. (1974). Prehistory of North America. New York.

- Martin, Brenda, et al. (2009). The Excavation of Lindenmeier: A Folsom Site Uncovered 1934–1940

- Rippeteau, Bruce Estes. (1979). A Colorado Book of the Dead: The Prehistoric Era. Denver.

- Wilmsen, Edwin N. (1974). Lindenmeier: A Pleistocene Hunting Society. New York.

- Wormington, H. M. (1957). Ancient Man in North America. Denver.

External links

edit- The Excavation of Lindenmeier

- National Historic Landmarks Programm: Lindenmeier site

- City of Fort Collins: Soapstone Prairie Management Plan

- The Claude C. and A. Lynn Coffin Lindenmeier Collection, Colorado State University Master's Thesis 2002

- A Tour of the Lindenmeier/Folsom Site

- Collection of newspaper articles about the site

- Soapstone Prairie Natural Area